Applied Visual Arts in the North Coolo O O O O O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ateneum's Spring 2018 Exhibitions to Feature Adel Abidin and Italian

Press release 7 Sept 2017 / Free for publication The Ateneum's spring 2018 exhibitions to feature Adel Abidin and Italian art The von Wright Brothers exhibition will open the Ateneum's winter season by presenting landscapes, still lifes, images of nature, and scientific illustrations by Magnus, Wilhelm and Ferdinand von Wright. In February, an exhibition of works by the contemporary artist Adel Abidin will explore the relationship between power and identity. In May, the halls on the third floor will be taken over by Italian art from the 1920s and 1930s. Exhibitions at the Ateneum Art Museum The von Wright Brothers 27 Oct 2017–25 Feb 2018 The exhibition will offer new perspectives on the work of the artist brothers Magnus, Wilhelm and Ferdinand von Wright, who lived during the period of the Grand Duchy of Finland. In addition to the familiar nature depictions and scientific illustrations, the exhibition will present an extensive display of landscapes and still lifes. The brothers' works will be accompanied by new art by the photographic artist Sanna Kannisto (born 1974) and the conceptual artist Jussi Heikkilä (born 1952). The historical significance of the von Wright brothers for Finnish art, culture and science is explored through 300 works. In addition to oil paintings, watercolours, prints and sketches, exhibits will include birds stuffed by Magnus von Wright, courtesy of the Finnish Museum of Natural History. The chief curator of the exhibition is Anne-Maria Pennonen. The Ateneum last staged an exhibition of works by the von Wright brothers in 1982. The exhibition is part of the programme celebrating the centenary of Finland's independence. -

Foster, Morgan with TP.Pdf

Foster To my parents, Dawn and Matt, who filled our home with books, music, fun, and love, and who never gave me any idea I couldn’t do whatever I wanted to do or be whoever I wanted to be. Your love, encouragement, and support have helped guide my way. ! ii! Foster ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Roberta Maguire for her priceless guidance, teaching, and humor during my graduate studies at UW-Oshkosh. Her intellectual thoroughness has benefitted me immeasurably, both as a student and an educator. I would also like to thank Dr. Don Dingledine and Dr. Norlisha Crawford, whose generosity, humor, and friendship have helped make this project not only feasible, but enjoyable as well. My graduate experience could not have been possible without all of their support, assistance, and encouragement. ! iii! Foster TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction..........................................................................................................................v History of African American Children’s and Young Adult Literature ......................... vi The Role of Early Libraries and Librarians.....................................................................x The New Breed............................................................................................................ xiv The Black Aesthetic .................................................................................................... xvi Revelation, Not Revolution: the Black Arts Movement’s Early Influence on Virginia Hamilton’s Zeely ............................................................................................................1 -

Night Walking: Darkness and the Sensory Perception of Landscape

Edinburgh Research Explorer Night walking: darkness and sensory perception in a night-time landscape installation Citation for published version: Morris, NJ 2011, 'Night walking: darkness and sensory perception in a night-time landscape installation', Cultural Geographies, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 315-342. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474011410277 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1177/1474474011410277 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Cultural Geographies Publisher Rights Statement: Published in Cultural Geographies by SAGE Publications. Author retains copyright (2011) General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 Night Walking: darkness and sensory perception in a night-time landscape installation Dr Nina J Morris School of GeoSciences University of Edinburgh Drummond Street Edinburgh, UK EH8 9XP [email protected] This is the author’s final draft as submitted for publication. The final version was published in Cultural Geographies by SAGE Publications, UK. Author retains copyright (2011) Cite As: Morris, NJ 2011, 'Night walking: darkness and sensory perception in a night- time landscape installation' Cultural Geographies, vol 18, no. -

Layout 1 Copy

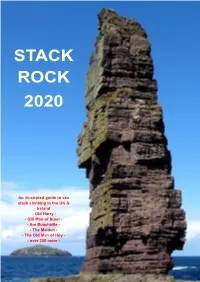

STACK ROCK 2020 An illustrated guide to sea stack climbing in the UK & Ireland - Old Harry - - Old Man of Stoer - - Am Buachaille - - The Maiden - - The Old Man of Hoy - - over 200 more - Edition I - version 1 - 13th March 1994. Web Edition - version 1 - December 1996. Web Edition - version 2 - January 1998. Edition 2 - version 3 - January 2002. Edition 3 - version 1 - May 2019. Edition 4 - version 1 - January 2020. Compiler Chris Mellor, 4 Barnfield Avenue, Shirley, Croydon, Surrey, CR0 8SE. Tel: 0208 662 1176 – E-mail: [email protected]. Send in amendments, corrections and queries by e-mail. ISBN - 1-899098-05-4 Acknowledgements Denis Crampton for enduring several discussions in which the concept of this book was developed. Also Duncan Hornby for information on Dorset’s Old Harry stacks and Mick Fowler for much help with some of his southern and northern stack attacks. Mike Vetterlein contributed indirectly as have Rick Cummins of Rock Addiction, Rab Anderson and Bruce Kerr. Andy Long from Lerwick, Shetland. has contributed directly with a lot of the hard information about Shetland. Thanks are also due to Margaret of the Alpine Club library for assistance in looking up old journals. In late 1996 Ben Linton, Ed Lynch-Bell and Ian Brodrick undertook the mammoth scanning and OCR exercise needed to transfer the paper text back into computer form after the original electronic version was lost in a disk crash. This was done in order to create a world-wide web version of the guide. Mike Caine of the Manx Fell and Rock Club then helped with route information from his Manx climbing web site. -

1 Update Report on the Winning Years Prepared for the Scottish

Update Report on The Winning Years Prepared for the Scottish Parliament’s Economy, Energy and Tourism Committee 9 September 2013 INTRODUCTION This report updates the Scottish Parliament’s Economy, Energy and Tourism Committee on the activity and results from The Winning Years; eight milestones over three years which VisitScotland and partners have been promoting to, and working with, the tourism industry on. The overall ambition behind the development of the Winning Years concept is to ensure that the tourism industry and wider visitor economy is set to take full advantage of the long-term gains over the course of the next few years. The paper is divided into sections covering each of the milestones: Year of Creative Scotland The 2012 London Olympics The Diamond Jubilee Disney.Pixar’s Brave Year of Natural Scotland The Commonwealth Games The 2014 Ryder Cup Homecoming Scotland 2014 (incl. up to date list of events) From this report Committee members will see that excellent progress has been made, with strong interest in Scotland’s tourism product from around the world as the country builds to welcome the world in 2014. All of this despite the continuing global economic difficulties. Evidence of bucking the global trend and the success of the 2012 Winning Years milestones can be seen in VisitScotland’s announcement at the end of August that its two main marketing campaigns brought nearly £310m additional economic benefit for Scotland since January 2012. This is a rise of 14% on the same period the year before. VisitScotland’s international campaigns target Scotland’s main markets across the globe including North America, Germany and France as well as emerging markets, such as India and China. -

Reality Is Broken a Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World E JANE Mcgonigal

Reality Is Broken a Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World E JANE McGONIGAL THE PENGUIN PRESS New York 2011 ADVANCE PRAISE FOR Reality Is Broken “Forget everything you know, or think you know, about online gaming. Like a blast of fresh air, Reality Is Broken blows away the tired stereotypes and reminds us that the human instinct to play can be harnessed for the greater good. With a stirring blend of energy, wisdom, and idealism, Jane McGonigal shows us how to start saving the world one game at a time.” —Carl Honoré, author of In Praise of Slowness and Under Pressure “Reality Is Broken is the most eye-opening book I read this year. With awe-inspiring ex pertise, clarity of thought, and engrossing writing style, Jane McGonigal cleanly exploded every misconception I’ve ever had about games and gaming. If you thought that games are for kids, that games are squandered time, or that games are dangerously isolating, addictive, unproductive, and escapist, you are in for a giant surprise!” —Sonja Lyubomirsky, Ph.D., professor of psychology at the University of California, Riverside, and author of The How of Happiness: A Scientific Approach to Getting the Life You Want “Reality Is Broken will both stimulate your brain and stir your soul. Once you read this remarkable book, you’ll never look at games—or yourself—quite the same way.” —Daniel H. Pink, author of Drive and A Whole New Mind “The path to becoming happier, improving your business, and saving the world might be one and the same: understanding how the world’s best games work. -

BURRA and TRONDRA COMMUNITY COUNCIL MINUTES a Virtual Meeting of the Above Community Council Was Held on Zoom on Monday 24Th August 2020 at 7Pm

Minute subject to approval at the next Community Council Meeting BURRA AND TRONDRA COMMUNITY COUNCIL MINUTES A virtual meeting of the above Community Council was held on Zoom on Monday 24th August 2020 at 7pm. Present Mr. N. O’Rourke Mr. G. Laurenson Miss N. Fullerton Mrs M. Garnier Ms. G. Hession Apologies Miss A. Williamson Mr. B. Adamson Mr. R. Black Mr. Michael Duncan, SIC Mrs. Roselyn Fraser, SIC In Attendance Mrs. J. Adamson (Clerk) Cllr. M. Lyall Cllr. I Scott 1. MINUTES OF LAST MEETING The Minutes of 21st July 2020 were approved by Gary Laurenson and Mhairi Garnier. 2. MATTERS ARISING (a) War Memorial, Bridge End – Grant for repairs Further photographs were submitted to accompany our Grants pre-application form to the War Memorial Trust back in March and they acknowledged receipt by e-mail on 4th March. They advised that the enquiry would undergo a preliminary assessment but due to the volume of work facing the charity they said it may take up to two months before they can provide us with a response. They asked that we do not contact them to chase our enquiry within the next 8 weeks and they will reply as soon as possible but could not guarantee any timeframes. (Our reference No is WMO/153611.) Nothing further had been heard from them. (b) Streetlights – Brough Mervyn Smith, SIC, advised by e-mail on 1st October 2019 that these two columns are scheduled for replacement next financial year (2020/21). It was agreed that this would be kept on the minutes until this is done. -

Dalziel + Scullion – CV

Curriculum Vitae Dalziel + Scullion Studio Dundee, Scotland + 44 (0) 1382 774630 www.dalzielscullion.com Matthew Dalziel [email protected] 1957 Born in Irvine, Scotland Education 1981-85 BA(HONS) Fine Art Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design, Dundee 1985-87 HND in Documentary Photography, Gwent College of Higher Education, Newport, Wales 1987-88 Postgraduate Diploma in Sculpture and Fine Art Photography, Glasgow School of Art Louise Scullion [email protected] 1966 Born in Helensburgh, Scotland Education 1984-88 BA (1st CLASS HONS) Environmental Art, Glasgow School of Art Solo Exhibitions + Projects 2016 TUMADH is TURAS, for Scot:Lands, part of Edinburgh’s Hogmanay Festival, Venue St Pauls Church Edinburgh. A live performance of Dalziel + Scullion’s multi-media art installation, Tumadh is Turas: Immersion & Journey, in a "hauntingly atmospheric" venue with a live soundtrack from Aidan O’Rourke, Graeme Stephen and John Blease. 2015 Rain, Permanent building / pavilion with sound installation. Kaust, Thuwai Saudia Arabia. Nomadic Boulders, Permanent large scale sculptural work. John O’Groats Scotland, UK. The Voice of Nature,Video / film works. Robert Burns Birthplace Museum. Alloway, Ayr, Scotland, UK. 2014 Immersion, Solo Festival exhibition, Dovecot Studios, Edinburgh as part of Generation, 25 Years of Scottish Art Tumadh, Solo exhibition, An Lanntair Gallery, Stornoway, Outer Hebrides, as part of Generation, 25 Years of Scottish Art Rosnes Bench, permanent artwork for Dumfries & Galloway Forest 2013 Imprint, permanent artwork for Warwick University Allotments, permanent works commissioned by Vale Of Leven Health Centre 2012 Wolf, solo exhibition at Timespan Helmsdale 2011 Gold Leaf, permanent large-scale sculpture. Pooley Country Park, Warwickshire. -

Download Download

SCULI'Tl/KED SLAB FRO ISLANE MTH BVKKA,F DO SHETLAND9 19 . ir. NOTIC A SCULPTURE F O E D SLAB FROE ISLANTH M F BURRADO , SHETLAND GILBERY B . T GOUDIE, F.S.A. SCOT. This unique monument, now safely deposited in the Museum of the Society, camo under my eye in the course of investigations which I made in the Burra Isles on the occasion of a visit to Shetland in the month of July 1877. Eichly sculpture wits i t wheel-croshi a s da f eleganso t design, with interlaced ornamentation of Celtic pattern, and a variety of figure subjects carefull ye ranke b executedy dma amont i , e foremosth g n i t interese Sculptureth f o t d Stone f Scotland o t si lay s , A wite . th h decorated side uppermost shora t a ,t distanc e churce soutth th f ho o eht in the ancient churchyard at Papil, it might have been noticed at any time by any one who chose to look for it, or who, chancing to observe it, had recognised its significanc a reli f s Christiao a ce t froar n ma perio f o d remote antiquity. But from age to age it appears to have escaped notice. Th Statisticaw e parisNe e th h l d clergymeAccountan d wroto Ol e snwh e th distric e e yearoth fth n si t 179 184d 9an 1 respectively, see havmo t e been unawar y othes existencit an rf f o o esculpture r o e d t i remains s i r no , noticed by any authors, natives or strangers, who have published accounts of the country from time to time, though the site is of more than ordinary interest ecclesiologically, from the fact of its having been occupied formerly by one of the towered churches of the north, of which that on the island of Egilsa Orknen y i e onlth ys y i preserved specimen s wila , l afterwards shown.e stonb e pass Th ha et memory marke e restindth ge placth f o e members of the family of Mr John Inkster, Baptist missionary in the island case s usua f th sucA eo n .i lh beed relicsha n t i regarde, n a s da importation t soma , e unknown period, from East.e "th " Beyond thio sn traditional idea appear havo st e been preserved regardin. -

No Longer and Not Yet

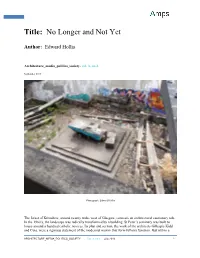

1 Title: No Longer and Not Yet Author: Edward Hollis Architecture_media_politics_society. vol. 3, no.2. September 2013 Photograph: Edward Hollis The forest of Kilmahew, around twenty miles west of Glasgow, conceals an architectural cautionary tale. In the 1960’s, the landscape was radically transformed by a building. St Peter’s seminary was built to house around a hundred catholic novices. Its plan and section, the work of the architects Gillespie Kidd and Coia, were a rigorous statement of the modernist maxim that form follows function. But within a ARCHITECTURE_MEDIA_POLITICS_SOCIETY Vol. 3, no.2. July 2013 1 2 decade, there were not enough priests to fill it; and St Peter’s became a form without a function. That was 1987, and since then it has resisted numerous attempts to provide it with a new one: designed as closely as it was to a specific programme, the building remains empty, and derelict. It is no longer what it used to be, and not yet what it can be. The caution is simple: design a building programmatically, and you’ll end up with a ruin. This author has been involved since the Venice Biennale of 2010 with a new proposal for St Peter’s led by the Glasgow arts collective NVA (Nacionale Vitae Activa). We have no images of what it will look like, or when it will be ready. St Peter’s isn’t going to be restored any time soon. Instead, we propose to leave the building perpetually incomplete – both ruin and building site. It’s a model of what all buildings should be: they are, in environmental terms, expensive. -

Suomalaisen Metsäluonnon Lukutaidon Historiaa –

Suomalaisen metsäluonnon lukutaidon historiaa – Ihmisen ja koivun muuttuva suhde Suomessa 1730-luvulta 1930-luvulle Turun yliopisto Historian laitos Suomen historia Lisensiaatintutkimus Maaliskuu 2005 Seija A. Niemi TURUN YLIOPISTO Historian laitos/Humanistinen tiedekunta NIEMI, SEIJA A.: Suomalaisen metsäluonnon lukemisen historiaa - ihmisen ja koivun muuttuva suhde Suomessa 1730-luvulta 1930-luvulle Lisensiaatintutkimus, 198 s. Suomen historia Maaliskuu 2005 Tutkimus on perustutkimus suomalaisten metsäluonnon lukutaidosta ja käsityksistä koivusta ja sen käytöstä kahdensadan vuoden ajalta. Valitun ajanjakson sisällä on ollut mahdollista havaita sekä perinteisen maanviljelyajan että teollisen ajan metsäluonnon lukutaidon yhtäläisyydet ja erot. Yhteistä koko jaksolle on ollut huoli metsien riittävyydestä ja oikeasta hoidosta. Eroja on ollut metsänkäyttötavoissa perinteisen luontaistalouden muututtua teollisuuden ajan kulutusyhteiskunnaksi. Tutkimuksen pääkysymykset ovat:1) Miten suomalaisten metsäluonnon lukutaito ja käsitykset koivusta ja sen resursseista ovat muuttuneet 1730-luvulta 1930-luvulle ja 2) mitkä seikat ovat näihin muutoksiin vaikuttaneet? Tutkimuksen esimerkkinä metsäluonnon lukemisesta on suomalaisten suhde koivuun. Tutki- muksessa tarkastellaan ympäristön lukutaidon avulla, miten ihminen ymmärtää ja tulkitsee ympäristöään tässä tutkimuksessa metsäluontoa. Ympäristön lukutaito on kokonaisvaltaista luonnon ymmärtämistä, tulkitsemista ja määrittelemistä huomioiden, elämysten, arvojen, asenteiden ja tiedon avulla. Taidon perustana -

The Media-Real (Final

The Rise of the MediaReal: Representation, the Real and September 11, 2001 By Jodie Florence Vaile BA (CS) University of Newcastle A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Canberra September 2010. Abstract On the 11th of September 2001 the world witnessed an unparalleled type of catastrophic event; the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Centre, the Pentagon and the attempted attack on the White House. One of the key factors making these attacks so unprecedented was that the second plane was caught live on television as it struck the second tower, as were the subsequent collapses of the two towers. To a large degree the events of this day were broadcast live to a mass global audience and it was this mediation that set the event apart. The mediation of this event was, on so many levels, more important than the event itself. It was not the first terrorist attack on a Western country, it did not cause the greatest loss of life of any catastrophic event, in a hypermediated world it was not even the most spectacular thing to appear on a television screen, yet no other event in recent history comes close to the level of effect that September 11 has had. This is the central concern that began the journey of this thesis, how did the representation of this event shape what possible societal perceptions of reality were available? This thesis is an exploration of why this event in particular has had the impact that it has and it is through this exploration of these issues that I propose this new model of the communication of spectacular catastrophic events – the media‐real.