Benefits and Barriers to the Consumption of A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fun with Foodella

Fun with Foodella Fun with Foodella is a nutrition education activity book designed for second grade students. This is the second major revision of the original Food Fun with Foodella, which was undertaken as a pilot project by seven South Dakota elementary school teachers in the summer of 1975 to strengthen nutrition education for students at the second grade level. The first revision occurred in 1992. This revision and reprinting was initiated at the prompting of elementary teachers who had previously used the workbook in their classes. The 2006 Fun with Foodella follows the updated food guidance system known as MyPyramid introduced by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 2005. Using the Teacher’s Guide The Fun with Foodella Teacher’s Guide provides the objectives and directions for each unit of the Fun with Foodella workbook. The directions include the background information necessary to teach each unit. Also, for each unit, additional ideas/activities are provided to further enhance and reinforce the student’s learning. Please be aware that by nature websites and web addresses change over the course of time. Hopefully we have provided enough background with each website given that you will be able to find additional information as necessary. 1 Acknowledgements The researching, writing and graphics necessary to move Fun with Foodella into the electronic age as well as make it compatible with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s MyPyramid, involved time and input from a myriad of people. It involved individuals from the South Dakota departments of Health and Education, South Dakota State University, Lower Brule Community College and the private sector. -

Eating for 2 Degrees New and Updated Livewell Plates Summary Report © J Oh N D a I E Ls / WWF

EATING FOR 2 DEGREES NEW AND UPDATED LIVEWELL PLATES SUMMARY REPORT © J OH N D A N I E LS / WWF Cover photo © Kelly Sillaste / Getty Images / WWF Contributors Gerard Kramer, Bart Durlinger, Lody Kuling, Willem-Jan van Zeist, Hans Blonk, Roline Broekema, Sarah Halevy Design madenoise.com CONTENTS May 2017 FOREWORD .............................................................................................4 About WWF KEY FINDINGS ........................................................................................6 WWF is the world’s leading independent conservation organisation. We’re CAll TO ACTION ...................................................................................7 creating solutions to the most important environmental challenges facing the WHAT WE SET OUT TO DO ...............................................................8 planet. We work with communities, businesses and governments in over METHODOLOGY .....................................................................................9 100 countries to help people and nature thrive. Together, we’re safeguarding the LIVEWell PRINCIPLES .................................................................... 10 natural world, tackling dangerous climate change and enabling people to use only ADULT 2020 PlATE ...........................................................................11 their fair share of natural resources. ADULT 2030 PlATE .......................................................................... 12 Food is at the heart of many key environmental issues -

Meat and Muscle Biology™ Introduction

Published June 7, 2018 Meat and Muscle Biology™ Meat Science Lexicon* Dennis L. Seman1, Dustin D. Boler2, C. Chad Carr3, Michael E. Dikeman4, Casey M. Owens5, Jimmy T. Keeton6, T. Dean Pringle7, Jeffrey J. Sindelar1, Dale R. Woerner8, Amilton S. de Mello9 and Thomas H. Powell10 1University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706, USA 2University of Illinois, Urbana, IL 61801, USA 3University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA 4Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS 66506, USA 5University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR 72701, USA 6Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA 7University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA 8Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523, USA 9University of Nevada, Reno, NV, 89557, USA 10American Meat Science Association, Champaign, IL 61820, USA *Inquiries should be sent to: [email protected] Abstract: The American Meat Science Association (AMSA) became aware of the need to develop a Meat Science Lexi- con for the standardization of various terms used in meat sciences that have been adopted by researchers in allied fields, culinary arts, journalists, health professionals, nutritionists, regulatory authorities, and consumers. Two primary catego- ries of terms were considered. The first regarding definitions of meat including related terms, e.g., “red” and “white” meat. The second regarding terms describing the processing of meat. In general, meat is defined as skeletal muscle and associated tissues derived from mammals as well as avian and aquatic species. The associated terms, especially “red” and “white” meat have been a continual source of confusion to classify meats for dietary recommendations, communicate nutrition policy, and provide medical advice, but were originally not intended for those purposes. -

5 a Day Month Recipes

Fruit and Veggie Recipes Out of This Whirled Shake Preparation Time: 5 minutes Makes 2 servings (½ cup fruit per person) ½ banana, peeled and sliced 1 cup unsweetened frozen berries (strawberries, blueberries, and/or blackberries) ½ cup low fat (1%) milk or soft tofu ½ cup 100% orange juice • Place all ingredients in a blender container. Cover tightly. • Blend until smooth. If mixture is too thick, add ½ cup cold water and blend again. • Pour into 2 glasses and serve. Nutrients per serving made with low fat milk and blueberries: 120 calories, 1g fat, 0g saturated fat, 0g trans fat, 5mg cholesterol, 40mg sodium, 26g carbohydrate, 3g dietary fiber, 3g protein. Diabetic Exchanges: 2 fruit. This set of recipes was originally developed by the Network for a Healthy California and has been adapted by the New Hampshire Fruit and Vegetable Program in collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to meet the Fruits & Veggies—More Matters® recipe criteria. NH DHHS y DPHS y Fruit and Vegetable Program y 603-271-4830 y www.dhhs.nh.gov/DHHS/NHP/fruitsandveggies y Jan 2008 y Page 1 of 10 Oprah’s Outtasight Salad Makes 4 servings (½ cup fruits and vegetables per person) Preparation Time: 20 minutes Salad 2 cups salad greens of your choice 1 cup chopped vegetables of your choice (tomatoes, cucumbers, carrots, green beans) 1 cup fresh orange segments or canned* pineapple chunks, drained (canned fruit packed in 100% fruit juice) ¼ cup Dynamite Dressing 2 tablespoons raisins or dried cranberries 2 tablespoons chopped nuts, any kind *canned fruit packed in 100% fruit juice. -

Don't Fall for Tricky Meat & Poultry Claims

Lean? here do Wthe bro- chures, posters, and voluntary labels for meat get their num- bers? In most Don’t fall for tricky meat cases, from the USDA’s data- & poultry claims base. And where does the USDA BY LINDSAY MOYER & JENNIFER URBAN gets its numbers? 0" trim? Fat chance. It’s no secret that Americans need to cut back on meat. While we Mostly from, or now eat more chicken than beef, we still eat too much red meat, with funding from, the beef and pork industries. Hmm... especially beef. That’s bad news for our health and for the planet. The USDA’s database has numbers for beef that has had People who eat more red meat—especially processed meat—have the fat around its edges trimmed down to just ⁄8” or 0”. a higher risk of colon cancer, heart disease, and stroke. (The pork industry never even says how much its cuts were trimmed.) And it doesn’t help that misleading information about meat or The USDA also has numbers for what’s called “separable poultry can trick even the most careful shoppers. Here’s what to lean.” That’s after scalpel-wielding technicians trim off the watch out for. “separable fat”—every bit of fat except marbling within the muscle. Missing labels? All that trimming (where do you keep your scalpel?) helps explain how the beef industry’s website can end up touting voluntarily, you’re 38 cuts of “lean” beef. The list even includes fatty cuts like stuck with a brochure New York strip steak and brisket. -

T. Colin Campbell, Ph.D. Thomas M. Campbell II

"Everyone in the field of nutrition science stands on the shoulders of Dr. Campbell, who is one of the giants in the field. This is one of the most important books about nutrition ever written - reading it may save your life." - Dean Ornish, MD THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE STUDY OF NUTRITION EVER CONDUCTED --THE-- STARTLING IMPLICATIONS FOR DIET, WEIGHT Loss AND LONG-TERM HEALTH T. COLIN CAMPBELL, PHD AND THOMAS M. CAMPBELL II FOREWORD BY JOHN ROBBINS, AUTHOR, DIET FOR A NEW AMERICA PRAISE FOR THE CHINA STUDY "The China Study gives critical, life-saving nutritional information for ev ery health-seeker in America. But it is much more; Dr. Campbell's expose of the research and medical establishment makes this book a fascinating read and one that could change the future for all of us. Every health care provider and researcher in the world must read it." -JOEl FUHRMAN, M.D. Author of the Best-Selling Book, Eat To Live . ', "Backed by well-documented, peer-reviewed studies and overwhelming statistics the case for a vegetarian diet as a foundation for a healthy life t style has never been stronger." -BRADLY SAUL, OrganicAthlete.com "The China Study is the most important book on nutrition and health to come out in the last seventy-five years. Everyone should read it, and it should be the model for all nutrition programs taught at universities, The reading is engrossing if not astounding. The science is conclusive. Dr. Campbells integrity and commitment to truthful nutrition education shine through." -DAVID KLEIN, PublisherlEditor Living Nutrition MagaZine "The China Study describes a monumental survey of diet and death rates from cancer in more than 2,400 Chinese counties and the equally monu mental efforts to explore its Significance and implications for nutrition and health. -

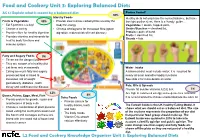

Food and Cookery Unit 3: Exploring Balanced Diets

Food and Cookery Unit 3: Exploring Balanced Diets AC 1.1 Explain what is meant by a balanced diet Portion Control! 38% Starchy Foods Healthy diets not only have the correct balance, but have Fruits & Vegetables 40% • Provide slow release carbohydrate used by the the right portion sizes. Here is a ‘handy’ guide… • Eat 5 portions s a day! body for energy Vegetables = double cupped palm. • Choose a variety • Choose wholegrains for increased fibre (good Grains/Starches = clenched fist. • Provides fibre for healthy digestion digestion, reduced risk of heart disease) Protein = palm of hand. • Provides vitamins and minerals for Fruits = clenched fist. Thumb = fats. healthy body functions and immune system Fatty and Sugary Foods 0% • These are the danger foods! • They are not part of a healthy diet • Eat them only occasionally Water Intake • Eating too much fatty and sugary A balanced diet must include water, it is required for processed food is linked to nearly all brain and other bodily functions increased risk of weight See slide 2 for more details on water gain/obesity, diabetes , tooth Fats, Oils & Spreads decay and cardiovascular disease Provide fat soluble vitamins A,D,E & K 1% 12% Are high in calories & energy so keep use to a minimum Beans, Pulses, Eggs, Meat, Fish 8% Dairy Foods It is recommended to choose unsaturated oils like olive oil • Provide protein for growth, repair and • Provide calcium for maintenance of body cells healthy bones, teeth The Eatwell Guide is the UK Healthy Eating Model. It • Choose a combination of plant proteins and nails shows what we should eat as a balanced diet. -

Ingredients in Meat Products Rodrigo Tarté Editor

Ingredients in Meat Products Rodrigo Tarté Editor Ingredients in Meat Products Properties, Functionality and Applications iv Editor Rodrigo Tarté, Ph.D. Meat Science Research Research, Development & Quality Kraft Foods Inc. 910 Mayer Avenue Madison, Wisconsin 53704 USA ISBN: 978-0-387-71326-7 e-ISBN: 978-0-387-71327-4 DOI: 10.1007/978-0-387-71327-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2008939885 © Springer Science + Business Media, LLC 2009 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science + Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identifi ed as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper springer.com v Preface There is little doubt that today’s food industry is faced with a rapidly changing market landscape. The obvious need to continue to provide consumers with nutritious, delectable, safe, and affordable food products which are also profitable for food manufacturers, as well as the ongoing challenge of ensuring the delivery of adequate nutrition to hundreds of millions of disadvantaged people around the world, appears – at least as much as, if not more than, ever – to be at odds with the challenges posed by soaring energy and food commodity prices; fast-paced changes in consumer demographics, habits, and preferences; and the continual need to stay ahead of current and emerging food safety issues. -

Fabulous Fruits... Versatile Vegetables

FabulousFabulous fruits…fruits… Versatile vegetables Versatile vegetables n I get should e w ca my ow I at Ho kids kn “ o ea “I ruit t t m ore f s and v ore Putting the m ege vege tables. tables?” Guidelines But h ow?? into Practice ” June 2003 nges ora the o Center for Are nly “ foods w Nutrition Policy ith and Promotion vitam in C?” United States Department of Agriculture Any of these questions sound familiar? Fruits Home and and vegetables are key parts of your daily diet. Garden Bulletin No. HG-267-4 Everyone needs 5 to 9 daily servings of fruits and vegetables for the nutrients they contain and for general health. Nutrition and health may be reasons you eat certain fruits and vegetables, but there are many other reasons why you choose the ones you do. Perhaps it is because of taste, or Nutrition Tidbit physical characteristics such as crunchiness, Fruits and vegetables give you many of the nutrients juiciness, or bright colors. that you need: vitamins, minerals, dietary fi ber, You may eat some fruits and vegetables water, and healthful phytochemicals. Some are because of fond memories — like watermelon sources of vitamin A, while others are rich in vitamin or corn at cookouts, your mom’s green bean C, folate, or potassium. Almost all fruits and veg- casserole, or tomatoes your dad brought in etables are naturally low in fat and calories and none from the backyard garden. Or you may simply have cholesterol. All of these healthful characteristics like them because most are quick to prepare may protect you from getting chronic diseases, such and easy to eat. -

Reducing Carbohydrates

Contact us: St Richard’s Hospital Worthing & Southlands Hospital Spitalfield Land Lyndhurst Road Chichester Worthing West Sussex West Sussex PO19 6SE BN11 2DH Leaflet produced by University Hospitals Sussex Dietitians. For further information or to provide feedback please contact: St Richard’s Hospital : Tel: 01243 831498 Email: [email protected] Worthing & Tel: 01903 286779 Southlands Hospital: Email: [email protected] We are committed to making our publications as accessible as possible. If you need this document in an alternative format, for example, large print, Braille or a language other than English, please contact the Communications Office by emailing [email protected] or speak to a member of the Dietitians Department. Reducing Carbohydrates www.uhsussex.nhs.uk Department: Diabetes Dietitians Issue date: May 2021 Review date: May 2023 Author: University Hospitals Sussex Diabetes Dietitians Version: 2 Introduction This dietary advice sheet is for people with diabetes who would like to lose weight or improve the management of their diabetes. Reducing the amount of carbohydrate in the diet can help. What is diabetes? Diabetes is a condition where the amount of glucose (sugar) in the bloodstream becomes too high because the body cannot control it properly. The blood glucose level is normally kept in range by the hormone insulin, which is produced by the pancreas. Insulin controls blood glucose levels by allowing glucose to enter the cells so it can be used as fuel by the body. In people with diabetes there is either not enough insulin being produced, or it does not work as it should. There are three ways in which blood glucose control can be improved – by altering diet, by increasing exercise, and by taking medication, either in the form of tablets or insulin injections. -

Guide for Vegan Prisoners

This booklet has been produced by Guide VPSG and The Vegan Society for Vegan Published September 2012 Prisoners VPSG P.O. Box 194 Enfield, Middx, EN1 4YL Tel: 020 8363 5729 Website: www.vpsg.info Email: [email protected] Contents INTRODUCTIONINTRODUCTION Introduction, 1 Definition of a Vegan, 1 The aim of this booklet is to provide NOMS Guidelines on the Care of Vegans, 2 vegan prisoners with practical Basic beliefs, 2 information to help ensure that their Diet, 2 vegan requirements are provided, e.g. Purchase of Supplements and Remedies, 2 food, toiletries, shoes etc. Dress, 2 Toiletries, 2 In addition, to give guidance on how to Work, 2 gain access to vegan supplements or Recommended Practices in Catering, 3 herbal remedies. Storage and Meal Service, 3 There are various systems in place to Weekly Vegan Provisions, 3 provide equal opportunities to vegan Basic Guidelines for a Vegan Diet, 4 prisoners, but these can sometimes be Rainbow Fruit/Vegetables, 4 difficult to navigate without the relevant Selenium, 4 information. Please keep this booklet safe during your sentence as the Essential Fatty Acids, 4 information might prove useful. Magnesium and Calcium, 4 Whole Grain vs Refined, 4 Definition of a Vegan Hydrogenated Fat, 4 Seeds, 4 VEGANISM may be defined as a way B12/Iodine, 4 of living which seeks to exclude, as far Vitamin D, 4 as possible and practicable, all forms of Textured Vegetable Protein, 4 exploitation of, and cruelty to, animals Salt Reduction, 4 for food, clothing or any other purpose. 5-A-Day, 5 In dietary terms it refers to the Fruit, 5 practice of dispensing with all animal Rainbow Foods, 5 products, including meat, fish, poultry, Green, 5 eggs, animal milks, honey, and their Orange, 5 derivatives. -

Biomarkers of Meat and Seafood Intake: an Extensive Literature Review Cătălina Cuparencu1*† , Giulia Praticó1†, Lieselot Y

Cuparencu et al. Genes & Nutrition (2019) 14:35 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12263-019-0656-4 REVIEW Open Access Biomarkers of meat and seafood intake: an extensive literature review Cătălina Cuparencu1*† , Giulia Praticó1†, Lieselot Y. Hemeryck2†, Pedapati S. C. Sri Harsha3†, Stefania Noerman4, Caroline Rombouts2, Muyao Xi1, Lynn Vanhaecke2, Kati Hanhineva4, Lorraine Brennan3 and Lars O. Dragsted1 Abstract Meat, including fish and shellfish, represents a valuable constituent of most balanced diets. Consumption of different types of meat and fish has been associated with both beneficial and adverse health effects. While white meats and fish are generally associated with positive health outcomes, red and especially processed meats have been associated with colorectal cancer and other diseases. The contribution of these foods to the development or prevention of chronic diseases is still not fully elucidated. One of the main problems is the difficulty in properly evaluating meat intake, as the existing self-reporting tools for dietary assessment may be imprecise and therefore affected by systematic and random errors. Dietary biomarkers measured in biological fluids have been proposed as possible objective measurements of the actual intake of specific foods and as a support for classical assessment methods. Good biomarkers for meat intake should reflect total dietary intake of meat, independent of source or processing and should be able to differentiate meat consumption from that of other protein-rich foods; alternatively, meat intake biomarkers should be specific to each of the different meat sources (e.g., red vs. white; fish, bird, or mammal) and/or cooking methods. In this paper, we present a systematic investigation of the scientific literature while providing a comprehensive overview of the possible biomarker(s) for the intake of different types of meat, including fish and shellfish, and processed and heated meats according to published guidelines for biomarker reviews (BFIrev).