The Ancient Near East Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Report on Arabia Provincia Author(S): G

A Report on Arabia Provincia Author(s): G. W. Bowersock Source: The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 61 (1971), pp. 219-242 Published by: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/300018 Accessed: 07-09-2018 18:42 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/300018?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Roman Studies This content downloaded from 128.112.203.62 on Fri, 07 Sep 2018 18:42:34 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms A REPORT ON ARABIA PROVINCIA By G. W. BOWERSOCK (Plates xiv-xv) With the increasing sophistication of excavation and exploration our knowledge of the provinces of Rome has grown stunningly in recent years. It will, one may hope, continue to grow; but the prospect of further advances ought not to be a deterrent to periodic reassess- ment and synthesis. -

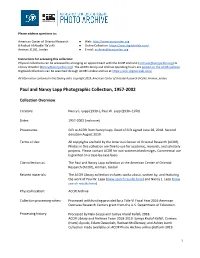

Paul and Nancy Lapp Collection Finding

Please address questions to: American Center of Oriental Research ● Web: http://www.acorjordan.org 8 Rashad Al Abadle Tla’a Ali ● Online Collection: https://acor.digitalrelab.com/ Amman 11181, Jordan ● E-mail: [email protected] Instructions for accessing this collection: Physical collections can be accessed by arranging an appointment with the ACOR Archivist ([email protected]) or Library Director ([email protected]). The ACOR Library and Archive operating hours are posted on the ACOR website. Digitized collections can be searched through ACOR’s online archive at https://acor.digitalrelab.com/. All information contained in this finding aid is Copyright 2019, American Center of Oriental Research (ACOR), Amman, Jordan. Paul and Nancy Lapp Photographic Collection, 1957-2002 Collection Overview Creators: Nancy L. Lapp (1930-), Paul W. Lapp (1930–1970) Dates: 1957-2002 (inclusive) Provenance: Gift to ACOR from Nancy Lapp. Deed of Gift signed June 28, 2018. Second donation August 2019. Terms of Use: All copyrights are held by the American Center of Oriental Research (ACOR). Photos in this collection are free to use for academic, research, and scholarly projects. Please contact ACOR for non-watermarked images. Commercial use is granted on a case-by-case basis. Cite collection as: The Paul and Nancy Lapp collection at the American Center of Oriental Research (ACOR), Amman, Jordan Related materials: The ACOR Library collection includes works about, written by, and featuring the work of Paul W. Lapp (View search results here) and Nancy L. Lapp (View search results here) Physical location: ACOR Archive Collection processing notes: Processed with funding provided by a Title VI Fiscal Year 2016 American Overseas Research Centers grant from the U.S. -

Viaggio Siria 1

Viaggio Siria – Giordania dal 14 aprile al 23 maggio 2010 passando per Grecia e Turchia . Siamo vicini alla partenza del nostro tour Siria-Giordania in camper con altri 13 camper per un totale di 26 persone. Il viaggio è organizzato dall’Unione Campeggiatori Bresciani con sede a Brescia , gli accompagnatori sono Camillo e Franca (Camillo è il vice-presidente dell’Unione Campeggiatori Bresciani). Il tour comprende visita a Siria e Giordania e sosta facoltativa a Istanbul (vedere programma sintetico) . La partenza è confermata da Ancona, mercoledì 14/4 ore 19,00 con la compagnia MINOAN LINES in “CAMPING ALL INCLUSIVE” che prevede la sistemazione del camper su ponte finestrato compresa l’elettricità, una cabina interna ed un pasto a tratta. Arrivo ad Igoumenitsa giovedì 15/4 ore 12,30 (17.30 ore di navigazione). E’ stata stipulata una polizza SANITARIA ed ASSISTENZA CAMPER (tipo europe-assistance) sottoscritta con FILO DIRETTO. Una cosa che non riperetemo nel diario di viaggio sono le piccole soste di almeno 30 minuti che facciamo con regolarità dopo aver viaggiato per circa 2 ore per relax-caffè-dolce-chiacchiere e le soste gasolio . Km alla partenza 41850 (seganti sul nostro contakilometri) Martedì 13 aprile 2010 – Km percorsi 374 Dopo aver preparato il camper con tutto il necessario per il viaggio, cibo, bevande, vestiti, libri e quanto utile ci avviamo con calma verso la casa di Monica per mangiare assieme e salutarci prima della partenza. Alle 19 arriviamo da loro, mangiamo e dopo le ultime coccole alla nostra stella Martina ci accompagnano al nostro camper e alle 22 circa comincia la nostra avventura. -

Jordan's Eastern Badia Trail Explore Desert Life Archaeology Biodiversity Ecology Geology

Jordan's Eastern Badia Trail Explore Desert Life Archaeology Biodiversity Ecology Geology wildjordan.com Table of Contents About Jordan’s Eastern Badia Trail (JEBT) Between Established and Proposed Reserves The Badia and the Desert Wildlife Birds JEBT Attractions Where to Stay Trails The Royal Society for the Black and White Trail Conservation of Nature Bedouins Trail Burqu Trail Created in 1966 under the patronage of His Badia Stories Trail Majesty the late King Hussein, The Royal Society Birds Trail for the Conservation of Nature (RSCN) is a non-governmental organization devoted to the Trails Routes conservation of Jordan’s natural environment. Activities Schedule JEBT Trails Map Wild Jordan Bedouin Life Wild Jordan is a registered trademark of The Royal What to Bring Society for the Conservation of Nature. Safety Wild Jordan’s revenue contributes to the sustainability Things to Take into Consideration of RSCN’s protected areas and supports the socio Weather economic development of local communities. How to Get There Rules and Regulations Trail Highlights Where in Jordan? • 4x4 off-roading • 10 attractions • 2 nature reserves and 1 proposed reserve • 100% local community employment • Best time to visit: Birds migration in autumn (September & October). Birds breeding season in spring (March & April) • Different desert ecosystems • Seasonal and customized desert activities and trails • Camping and lodging • People, landscape, history, wildlife, stories • Day and overnight trips • 7 Important Bird Areas • Bedouin experience • Proximity to Amman Trail Area About Jordan’s Eastern Badia Trail (JEBT) Jordan’s Eastern Badia Trail (JEBT) follows Between Established and the footsteps of nomadic Arab Bedouins across a seasonal, ever-changing, natural Proposed Reserves desert landscape that connects areas rich with ancient history, tradition, culture, archaeology, geology, flora and fauna. -

Download the Entire 2015-2016 Annual Report In

THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE 2015–2016 ANNUAL REPORT © 2016 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2016. Printed in the United States of America. The Oriental Institute, Chicago ISBN: 978-1-61491-035-0 Editor: Gil J. Stein Production facilitated by Emily Smith, Editorial Assistant, Publications Office Cover and overleaf illustration: Eastern stairway relief and columns of the Apadana at Persepolis. Herzfeld Expedition, 1933 (D. 13302) The pages that divide the sections of this year’s report feature images from the special exhibit “Persepolis: Images of an Empire,” on view in the Marshall and Doris Holleb Family Gallery for Special Exhibits, October 11, 2015, through September 3, 2017. See Ernst E. Herzfeld and Erich F. Schmidt, directors of the Oriental Institute’s archaeological expedition to Persepolis, on page 10. Printed by King Printing Company, Inc., Lowell, Massachusetts, USA CONTENTS CONTENTS INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION. Gil J. Stein ........................................................ 5 IN MEMORIAM . 7 RESEARCH PROJECT REPORTS ÇADıR HÖYÜK . Gregory McMahon ............................................................ 13 CENTER FOR ANciENT MıDDLE EASTERN LANDSCAPES (CAMEL) . Emily Hammer ........................ 18 ChicAGO DEMOTic DicTıONARY (CDD) . Janet H. Johnson .......................................... 28 ChicAGO HıTTıTE AND ELECTRONic HıTTıTE DicTıONARY (CHD AND eCHD) . Theo van den Hout ........... 33 DENDARA . Gregory Marouard................................................................ 35 EASTERN -

The Spatial Analysis of a Historical Phenomenon: Using GIS To

THE SPATIAL ANALYSIS OF AN HISTORICAL PHENOMENON: USING GIS TO DEMONSTRATE THE STRATEGIC PLACEMENT OF THE UMAYYAD "DESERT PALACES." MAHMOUD BASHIR ABDALLAH ALHASANAT UNIVERSITI SAINS MALAYSIA 2009 THE SPATIAL ANALYSIS OF AN HISTORICAL PHENOMENON: USING GIS TO DEMONSTRATE THE STRATEGIC PLACEMENT OF THE UMAYYAD "DESERT PALACES." by MAHMOUD BASHIR ABDALLAH ALHASANAT Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science January 2009 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Bism Allah wa al-hamdulellah wa ssallat wa salam Allah ‘ala saidna Muhammad. I am deeply indebted to my sweet, wonderful friend, Dr. Erin Addison, for her constant support and encouragement: without her help, this work would not be possible. I deeply thank my advisors, Prof. Norizan Md and Dr. Tarmiji Masron, whose help, advice, guidance and supervision was invaluable. Without them, this work could not have been completed. I also would like to thank all my lecturers, Prof. Ruslan, Dr. Narimah, Dr Wan and Dr. Ashirah, also Mr. Jahan and Mr. Faiyaz, for their time, efforts, understanding and patience during the period of my study. USM and its staff, is greatly acknowledged. Besides, I would like to thank Dr. Ali Abbas Albdour for his cameraderie. Finally I would also like to extend my deepest gratitude to my family. Without their encouragement I would not have a chance to be at USM. My brothers and sisters (Dr.Ahmed, Eng, Naeem, Eng. Riad , Eng. Mansour, Dr. Asa’ad, Ruqaia and Ola), their help, support and patience has been most appreciated. I especially owe much to my parents for their prayers for me. I dedicate this dissertation to my mother, father and to my country. -

The Oriental Institute 2012–2013 Annual Report

http://oi.uchicago.edu The OrienTal insTiTuTe 2012–2013 annual repOrT The OrienTal insTiTuTe 2012–2013 annual repOrT http://oi.uchicago.edu © 2013 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2013. Printed in the United States of America. The Oriental Institute, Chicago ISBN-13: 978-1-61491-016-9 ISBN-10: 1614910162 Editor: Gil J. Stein Cover and title page illustration: “Birds in an Acacia Tree.” Nina de Garis Davies, 1932. Tempera on paper. 46.36 × 55.90 cm. Collection of the Oriental Institute. Oriental Institute digital image D. 17882. Between Heaven & Earth Catalog No. 11. The pages that divide the sections of this year’s report feature images from last year’s special exhibit Between Heaven & Earth: Birds in Ancient Egypt. Printed through Four Colour Print Group, by Lifetouch, Loves Park, Illinois The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Services — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. ∞ http://oi.uchicago.edu contents contents introduction Introduction. Gil J. Stein ................................................................. 7 In Memoriam ........................................................................... 9 research Project Reports ...................................................................... 15 Archaeology of Islamic Cities. Donald Whitcomb........................................... 15 Center for Ancient Middle Eastern Landscapes (CAMEL). Scott Branting ..................... 18 Chicago Demotic -

Jordan Umayyad Route Jordan Umayyad Route

JORDAN UMAYYAD ROUTE JORDAN UMAYYAD ROUTE Umayyad Route Jordan. Umayyad Route 1st Edition, 2016 Edition Index Andalusian Public Foundation El legado andalusí Texts Introduction Talal Akasheh, Naif Haddad, Leen Fakhoury, Fardous Ajlouni, Mohammad Debajah, Jordan Tourism Board Photographs Umayyad Project (ENPI) 7 Jordan Tourism Board - Fundación Pública Andaluza El legado andalusí - Daniele Grammatico - FOTOGRAFIAJO Inc. - Mohammad Anabtawi - Hadeel Alramahi -Shutterstock Jordan and the Umayyads 8 Food Photographs are curtsy of Kababji Restaurant (Amman) Maps of the Umayyad Route 20 Graphic Design, layout and maps Gastronomy in Jordan 24 José Manuel Vargas Diosayuda. Diseño Editorial Free distribution Itineraries ISBN 978-84-96395-81-7 Irbid 36 Legal Deposit Number Gr- 1513 - 2016 Jerash 50 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, nor transmitted or recorded by any information Amman 66 retrieval system in any form or by any means, either mechanical, photochemical, electronic, photocopying or otherwise without written permission of the editors. Zarqa 86 © of the edition: Andalusian Public Foundation El legado andalusí Azraq 98 © of texts: their authors Madaba 114 © of pictures: their authors Karak 140 The Umayyad Route is a project funded by the European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument (ENPI) and led by the Ma‘an 150 Andalusian Public Foundation El legado andalusí. It gathers a network of partners in seven countries in the Mediterranean region: Spain, Portugal, Italy, Tunisia, Egypt, Lebanon and Jordan. This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union under the ENPI CBC Mediterranean Sea Basin Programme. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of the beneficiary (Fundación Pública Bibliography 160 Andaluza El legado andalusí) and their Jordanian partners [Cultural Technologies for Heritage and Conservation (CULTECH)] and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union or of the Programme’s management structures. -

Potenziale Des Dai Gazetteers Am Beispiel Der Sogenannten Wüstenschlösser Der Levante

WO LIEGT EIGENTLICH USEIS? POTENZIALE DES DAI GAZETTEERS AM BEISPIEL DER SOGENANNTEN WÜSTENSCHLÖSSER DER LEVANTE Sabine Thänert, M.A. Referat für Informationstechnologie/Wissenschaftliche Fachsäule, Deutsches Archäologisches Institut (DAI, www.dainst.org ), sabine. [email protected] KURZDARSTELLUNG: Als weltweit agierende Forschungseinrichtung ist das Deutsche Archäologische Institut (DAI) auf fünf Kontinenten in über 350 Projekten tätig. Ein Bestandteil der Arbeit ist die Erschließung und Bereitstellung von Wissensarchiven für die internationale Forschung. Besondere Bedeutung kommt hierbei der Entwicklung von Standards für die Archivierung digitaler Daten sowie der Generierung von normiertem Vokabular zu. Im Fokus stehen dabei in unserem Fall ortsbezogene Daten. Mit der Programmierung des DAI-Gazetteers wird derzeit zum einen ein Normdatenvokabular für alle ortsbezogenen Informationen des DAI geschaffen - inklusive Lokalisierung -, zum anderen sollen die mit Ortsdaten versehenen Informationsobjekte mit Ortsdatensystemen weltweit vernetzt werden. Am Beispiel der aus dem frühen Mittelalter stammenden sogenannten Wüstenschlösser in der Levante wird im Beitrag die Problematik der unterschiedlichen Schreibweisen und Bezeichnungen der Orte und Gebäude unter folgenden Aspekten beleuchtet: Skizzierung der Komplexität der Datenlage, Darstellung der Konsequenzen für Wissenschaft und Gedächtnisinstitutionen, Präsentation von Lösungen und Ausblick auf Perspektiven. Da es bisher keine Plattform gibt, die für diese - exemplarisch ausgewählte - Objektgruppe -

12ICAANE Program Web.Pdf

12TH INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS ON THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ANciENT NEAR EAST BOLOGNA APRIL 6-9, 2021 PROGRAM 12TH INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS ON THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST BOLOGNA APRIL 6-9, 2021 http://www.12icaane.unibo.it/ PARTNERS TECHNICAL PARTNERS SPONSORS ACADEMIC PUBLISHERS 3 12TH ICAANE ORGANIZING COMMITTEE 12TH ICAANE UNIBO EXECUTIVE TEAM Pierfrancesco CALLIERI Michael CAMPEGGI Maurizio CATTANI Vittoria CARDINI Enrico CIRELLI Francesca CAVALIERE Antonio CURCI Claudia D’ORAZIO (Scientific Secretary) Anna Chiara FARISELLI Valentina GALLERANI Henning FRANZMEIER Gabriele GIACOSA Elisabetta GOVI Elena MAINI Mattia GUIDETTI Eleonora MARIANI Francesco IACONO Chiara MATTIOLI Simone MANTELLINI Jacopo MONASTERO Gianni MARCHESI Valentina ORRÙ Nicolò MARCHETTI (Chair) Giulia ROBERTO Palmiro NOTIZIA Marco VALERI Adriano V. ROSSI Federico ZAINA Marco ZECCHI ICAANE INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE Pascal BUTTERLIN – University of Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne 12TH ICAANE SCIENTIFIC ADVISORY BOARD Bleda DÜRING – University of Leiden Marian FELDMAN – Johns Hopkins University Pascal BUTTERLIN – University of Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne Karin KOPETZKY – OREA, Austrian Academy of Sciences Peter FISCHER – University of Gothenburg Wendy MATTHEWS – University of Reading Tim HARRISON – University of Toronto Adelheid OTTO – Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Nicolò MARCHETTI – Alma Mater Studiorum - University of Bologna Frances PINNOCK – Sapienza University of Rome (Secretary General) Wendy MATTHEWS – University of Reading Ingolf THUESEN – University of Copenhagen -

Jordan Toponymic Factfiles

TOPONYMIC FACT FILE JORDAN Country name Jordan State title Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Name of citizen Jordanian Official language Arabic (ara)1 (Al Urdun2) اﻷردن Country name in official language Al Mamlakah al Urdunīyah al) المملكة اﻷردنية الهاشمية State title in official language Hāshimīyah) Script Arabic is written in Perso-Arabic script Romanization System BGN/PCGN Romanization System for Arabic 19563 ISO-3166 code (alpha-2/alpha-3) JO/JOR Capital Amman (Ammān4‘) عمان Capital in official language Population 9,814,9955 Area 88,794 km2 Introduction Jordan claimed its independence in 1946, when the United Nations (UN) approved the end of the British Mandate and recognised the Hashemite Kingdom of Transjordan as an independent country. In 1948 the name of the state was changed to the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan.6 Jordan lies on the East Bank of the Jordan River7, and is bordered by Israel and the West Bank to the west, Syria to the north, Iraq to the northeast, and Saudi Arabia to the east and south. Jordan also has a small coastline on the Red Sea8 (27 km). Geographical names policy Official geographical names in Jordan are found written in Arabic, which is the country’s official language. The Arabic-script names found on official sources should be romanized using the BGN/PCGN Romanization System for Arabic9 and all diacritical marks should be included where possible10. 1 The three-letter codes for languages provided in brackets in this document are the ISO 639-3 language codes. 2 Although Al Urdunn is found in the Hans Wehr Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic and Nigel Groom’s A Dictionary of Arabic Topography and Placenames, official Jordanian sources show a single –n-, i.e. -

University of Arizona CMES

Continuity and Change in Jordan: Social and Environmental Transformations – University of Arizona CMES Leave U.S. on Friday, May 29. Arrive Saturday, May 30, around midnight and overnight in Amman. Amman: Sunday, May 31: Take a brief city tour of Amman. Two hours of Arabic instruction. Overnight in Amman. Monday, June 1: Two hours of Arabic instruction. Visit a school. Visit the University of Jordan and meet with teacher-educators and pre-service teachers. Speaker from the university’s school of education. Overnight in Amman. Tuesday, June 2: Visit Amman’s Archeological Museum and the Citadel. Two hours of Arabic instruction. Speaker from the American Center of Oriental Research – “Archeology in Jordan” Overnight in Amman. Wednesday, June 3: Visit to King Abdullah Mosque with talk about Islam by a mosque employee. Speaker: Muhammad Tamimi “Effect of Palestinian-Israeli Conflict on Jordan” Two hours of Arabic instruction: Practicum, Part 1. (Explore daily life in Jordan by riding the bus, visiting the food market, etc. while learning the Arabic words and carrying out simple assigned tasks in Arabic.) Overnight in Amman Thursday, June 4: Jordanian and Arab Art: Visit the Nabad Gallery, Darat Al-Funun,, and National Gallery. Guided visit led by our tour guide. Two hours of Arabic instruction: Practicum, Part 2. (Explore daily life in Jordan while learning the Arabic words and carrying out simple assigned tasks in Arabic.) Overnight in Amman. Friday, June 5: Visit Wild Jordan Center in the morning (for their weekly market). 1 hour of Arabic practicum at the market (practicing food words and purchasing goods); 1 hour of Arabic in the afternoon.