Chapter 6: Participatory Action Research Cycle Two…………

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

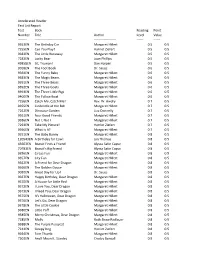

Accelerated Reader Test List Report Test Book Reading Point Number

Accelerated Reader Test List Report Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------- ---------------------------------- -------------------- ------ ------ 9353EN The Birthday Car Margaret Hillert 0.5 0.5 7255EN Can You Play? Harriet Ziefert 0.5 0.5 9382EN The Little Runaway Margaret Hillert 0.5 0.5 7282EN Lucky Bear Joan Phillips 0.5 0.5 49858EN Sit, Truman! Dan Harper 0.5 0.5 9018EN The Foot Book Dr. Seuss 0.6 0.5 9364EN The Funny Baby Margaret Hillert 0.6 0.5 9383EN The Magic Beans Margaret Hillert 0.6 0.5 9391EN The Three Bears Margaret Hillert 0.6 0.5 9392EN The Three Goats Margaret Hillert 0.6 0.5 9393EN The Three Little Pigs Margaret Hillert 0.6 0.5 9400EN The Yellow Boat Margaret Hillert 0.6 0.5 7256EN Catch Me, Catch Me! Rev. W. Awdry 0.7 0.5 9355EN Cinderella at the Ball Margaret Hillert 0.7 0.5 7262EN Dinosaur Garden Liza Donnelly 0.7 0.5 9361EN Four Good Friends Margaret Hillert 0.7 0.5 9386EN Not I, Not I Margaret Hillert 0.7 0.5 7293EN Take My Picture! Harriet Ziefert 0.7 0.5 9396EN What Is It? Margaret Hillert 0.7 0.5 9351EN The Baby Bunny Margaret Hillert 0.8 0.5 120543EN A Birthday for Cow! Jan Thomas 0.8 0.5 43663EN Biscuit Finds a Friend Alyssa Satin Capuc 0.8 0.5 70783EN Biscuit's Big Friend Alyssa Satin Capuc 0.8 0.5 9356EN Circus Fun Margaret Hillert 0.8 0.5 9357EN City Fun Margaret Hillert 0.8 0.5 9362EN A Friend for Dear Dragon Margaret Hillert 0.8 0.5 9366EN The Golden Goose Margaret Hillert 0.8 0.5 9020EN Great Day for Up! Dr. -

Biola University

Biola University Undergraduate Prospectus 03 We are restless. The world is full of things to know. Stories to tell, mysteries to solve, ideas to think and words to read. But together— People to meet and help and heal, together, we are a foundation for each other. prayers to pray and sunrises to see. Upon which each of us can build our futures. And be free to fall and fail and fumble and find our ways We are restless. and succeed Because there are things to do. over and over and over again— because we support each other. Individually, Lift each other up as we engage and impact the world. we are incomplete, inexperienced, imperfect. “This is a good place to struggle,” we say. As we seek out God in all things. In the twisted ladder of a double helix. In between the lines of literary masterpieces. In the research we conduct. And the conduits of the human mind. In all that we do. All that we are. All that we become. All as one. We We are We are restless. restless. 04 ACADEMICS Attracting the extraordinary and radiatingYou can feel it. The pull of this place. It calls you. impact. Draws in remarkable students from everywhere. And attracts exceptional faculty, too. Fulbright scholars, fellows, National Endowment for the Humanities grant recipients. Thought leaders who enjoy having the freedom to bring their faith to work every day—elevate it, incorporate it and wrestle with it—instead of leaving it at home. Here, Biola faculty can teach from their heads and their hearts. -

International Conference on Sport Pedagogy, Health and Wellness

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON SPORT PEDAGOGY, HEALTH AND WELLNESS 1 PE Plus: Retooling Physical Education for Inclusion, Development and Competition INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON SPORT PEDAGOGY, HEALTH AND WELLNESS International Conference on Sport Pedagogy, Health and Wellness (ICSPHW) Copyright © 2016 by the College of Human Kinetics, University of the Philippines, Diliman. All rights reserved. 2 PE Plus: Retooling Physical Education for Inclusion, Development and Competition INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON SPORT PEDAGOGY, HEALTH AND WELLNESS UNIVERSITY OF THE PHILIPPINES QUEZON CITY OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT MESSAGE I am privileged to welcome all the guests and participants of the 1st International Conference on Sport Pedagogy, Health and Wellness (ICSPHW). No less than the world's top experts in health, human movement, and pedagogy are gathered here today to discuss important physical education and sports science-related topics over the next three days. While UP's commitment to academic excellence has always been the cornerstone of our success, this has at times been incorrectly conflated with a pursuit of purely intellectual brilliance. This misconception, no doubt fed by the false dichotomy of mind and body, has led to the misconstrued notion attributing UP's contributions to society to purely mental feats. This is of course far from the truth, and does not bespeak of the kind of liberal education that UP has historically espoused. We are lucky and grateful that the UP College of Human Kinetics (UP CHK) has been fully committed to bucking the stereotype and has been showing how well-rounded the Filipino youth can be. Since assuming its name in 1989, the UP CHK has been the base of operations and primary nurturer of UP's student athletes and athletic organizations. -

2 in the US in International Students’ Overall Satisfaction with Their Educational Experience #127 Best US National Universities (U.S

Guide for International Students 2017-18 #61 Top Public Schools in the US #2 in the US in international students’ overall satisfaction with their educational experience #127 Best US National Universities (U.S. News & World Report 2016) 1 of 40 Public US universities with Carnegie Foundation's Tier 1 Very High Research Activity & Community Engagement designations #236 of the Best Global Universities (U.S. News & World Report 2016) Top 300 Best universities in the world (Times Higher Education 2016) Top 78 Universities in the US and Top 201 worldwide (Academic Ranking of World Universities 2014) #7 Environmental Science and Engineering program globally (Academic Rank of World Universities 2016) #2 Best university for language support (International Student Barometer 2013) Top 227 One of the top schools (Alumni Factor 2015) 4 Contents | Colorado State University 2017-18 Welcome to Colorado State University! If you are looking for a great education at one of the top universities in the US, welcome to Colorado State University. CSU’s roots date back to 1870, when the institution was founded and from these origins a world-class institution grew. Today, Colorado State’s campus encompasses over two million square meters and is home to 27,566 students, including 4,008 graduate students. CSU is also a Carnegie Class I research institution with annual research expenditures topping $317 million in 2015, placing us at the very top of American public research universities. CSU has helped international students make the most of their academic, social and cultural opportunities for over a century. Highly qualified university instructors, facilities equipped with the latest technology, small classes, support services, social activities and a welcoming university community all contribute to the students’ experience. -

UNDERGRADUATE CATALOG 2020 - 2021 Undergraduate Catalog 2020 - 2021

UNDERGRADUATE CATALOG 2020 - 2021 Undergraduate Catalog 2020 - 2021 An undergraduate catalog is published every year by the Millersville University Council of Trustees. This publication is announcement for the 2020-2021 academic year. The catalog is for informational purposes only and does not constitute a contract. The provisions of this catalog are not intended to create any substantive rights beyond those created by the laws and constitutions of the United States and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, and are not intended to create, in and of themselves, any cause of action against Pennsylvania’s State System of Higher Education, the Board of Governors, the Chancellor, an individual President or University, or any other officer, agency, agent or employee of Pennsylvania’s State System of Higher Education. Information contained herein was current at time of publication. Courses and programs may be revised; faculty lists and other information are subject to change without notice; course frequency is dependent on faculty availability. Not all courses are necessarily offered each session of each year. Individual departments should be consulted for the most current information. A Member of Pennsylvania’s State System of Higher Education P.O. Box 1002 Millersville, PA 17551-0302 www.millersville.edu 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS UNIVERSITY CALENDAR 2020-2021 ...........................................................5 AN INTRODUCTION TO MILLERSVILLE UNIVERSITY ............................7 History.............................................................................................................. -

Grading Scale • 9 AP Scholars • 24 AP Scholars with Honors the School Uses a 100 Point Grading Scale in Grades 9-12 and a 4.00 CGPA for Reporting

www.tasisengland.org SCHOOL PROFILE 2020-21 CEEB CODE : 724736 | UCAS CODE : 16088 | IB CODE : 2261 Our School Accreditation TASIS England was founded by Mrs. Mary Crist Fleming in 1976 as an American Council of International Schools (CIS) school located in Surrey, England, for students ages 3-18. We are a private, UK Department for Education URN: 125423 independent, co-educational, boarding and day school with students from 58 New England Association of Schools and Colleges (NEASC) countries, situated on 46 acres of beautiful Surrey land. The campus comprises International Baccalaureate Organization (IBO) buildings dating back to the 18th century with modern science, technology, art, theater, and athletic facilities. Examination Boards International Baccalaureate Organization (IBO) TASIS England believes in supporting an expertise beyond the curriculum and College Board Advanced Placement Program developing a pure passion for learning in our students. Membership Our Students and Faculty Educational Collaborative for International Schools (ECIS) • Upper school: 345 students Independent Schools Association (ISA) • Class of 2021: 102 students International Schools Athletic Association (ISAA) • Class of 2020: 107 students British Association of Independent Schools with International Students (BAISIS) • Student to faculty ratio is 6:1 Boarding Schools’ Association (BSA) • 70% of our teachers hold master’s and/or doctoral degrees • Median class size of 9.4 Extra-curricular and Sports Program TASIS England is a firm believer in combining curricular with extra-curricular Our Curriculum education to create a well-rounded student. All TASIS students must complete TASIS England offers only the most demanding academic program to its Upper the IB CAS requirements or our Community Service Program. -

U.S. University Success

2015 in partnership with Your first step to U.S. university success 02 Welcome to ONCAMPUS TEXAS 04 The University of North Texas ONCAMPUS TEXAS 06 Everything’s bigger in Texas is your pathway to accomplishment 08 The perfect campus 10 University Transfer Program ONCAMPUS Texas, located at the University of North Texas 12 Progression to UNT (UNT), is specially designed to provide you with skills for success - academically, socially and professionally. As a full ON 14 Why choose CAMPUS TEXAS time student, you will earn college credit towards your future 16 Academic Entry Requirements degree while also gaining a deeper understanding of Texas, the U.S. and its education system. 18 Program Details UNT is a large public, student-centered research university located in the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex. It is committed to advancing educational excellence and preparing students to become thoughtful, engaged citizens of the world. Founded in 1890 it is now the 25th largest university in the U.S. enrolling 36,000 students across 99 bachelors, 83 masters and 36 doctoral degree programs. ONCAMPUS Texas provides you with the tools needed to successfully start, and succeed, in your chosen degree program. ONCAMPUS TEXAS is proud to work in partnership with University of North Texas to offer a high- quality university transfer program for international students on a Eva I Turkey I MS I Radio and Television university campus. “My learning about the U.S. went far beyond the one class[room] at UNT, I want to work for the United Nations and contribute to Find out more: education and peace in any way that I can.” www.oncampususa.com/texas Facebook: www.facebook.com/oncampustexas Named Outstanding Foreign Student in North Texas for 2014 Preparation for your future WHY STUDY IN THE U.S.? • ONCAMPUS Texas helps international students succeed – academically, socially, and professionally Choices – no other country comes close to offering as many – with a one-year support program delivered at the learning options University of North Texas. -

2019-2020 Fact Book University of St

2019-2020 Fact Book University of St. Thomas Fact Book 2019 - 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Message from the President 2 Mission Statement 2 Values and Motto 2 The Call Toward Tomorrow 3 Academic Calendar 3 UST at a Glance 4 Governance 5 Students 8 Faculty 16 Administration 17 Alumni 18 Degree Programs 19 Academic Resources 22 Academic Programs 23 Financial Information 25 Endowment 25 Philanthropy 26 History 26 Accreditation and Memberships 31 Prayer for the University 32 The 2019 - 2020 UST Fact Book is compiled by the Office of Administrative Computing and Institutional Research Ms. Kelly Klitz Director of Applications Services , IT Mr. Michael Acosta Institutional Analyst. Cover Photo: Educating University Leaders of St. Thomasof Faith and CharacterHouston skyline THANK YOU FROM THE PRESIDENT Dear Friends, It has been a season of great growth and positive change at the University of St. Thomas. Record-setting incoming classes have blessed UST with more total students than we have ever had in the University’s history. Everywhere you look, the campus is alive and teaming with activity. As we continue to grow, we do so with a sharp focus on mission, so our impact on Houston and the world also continues to expand. Our motto, “Crescamus in Christo,” reminds us that we are called to grow not only in size, knowledge and wisdom, but also in love and service to Christ. Spring 2020 is shaping up to be the largest undergraduate spring class in University history. As our students graduate, I am pleased to also say that of those seeking jobs, 91% will find one within three months. -

Graduate Catalog 2020–21

Graduate Catalog 2020–21 Auburn University at Montgomery presents this catalog to its graduate students, prospective graduate students, employees and others to inform them about the admission process, degree programs and requirements, course descriptions, regulations, faculty members and other pertinent information. The statements made in this catalog are for informational purposes only and do not constitute a contract between the student and AUM. While Auburn University at Montgomery reserves the right to make changes to its policies, regulations, curriculum and other items listed in this catalog without actual notice to students, the information accurately reflects policy and progress requirements for graduation effective August 1, 2020. These changes will govern current and formerly enrolled students. Enrollment of all students is subject to these conditions. Auburn Montgomery will make every effort to keep students advised on any such changes. Information on changes will be available online at www.aum.edu. It is important that each student be aware of their individual responsibility to keep apprised of current graduation requirements for their degree program. I certify that this catalog is true and correct in content and policy as required by 38CFR21.4258(d)(1). Dr. Mrinal Mugdh Varma Provost and Senior Vice Chancellor GRAD CATALOG 2020—2021 1 Contents Letter from Provost ...........................................................................................................................................................1 Table -

Wheels Campus

FROM NEW MOBILITY MAGAZINE AND UNITED SPINAL ASSOCIATION WHEELS ONCAMPUS A GUIDE TO WHEELCHAIR-FRIENDLY HIGHER EDUCATION life beyond wheels WHEELS ON CAMPUS CONTENTS WHEELCHAIR FRIENDLY COLLEGES 9 TEN SCHOOLS THAT SET THE BAR HIGH Here are the pioneers and leaders that consistently offer a wide range of inclusive opportunities in a truly accessible setting. 43 TEN MORE SOLID CHOICES These colleges, each with its own distinctive character and wheelchair culture, round out the Top 20. THINKING OUTSIDE THE BOX THE FINE PRINT 31 COMMUNITY COLLEGES: WHERE CREATING 2 CONTRIBUTORS A UNIQUE PATH BEGINS 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 4 EDITOR’S NOTE 33 THE IMPORTANCE OF HISTORICALLY BLACK 6 METHODOLOGY COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES 61 RESOURCES 35 ACADEMICS OVER ACCOMMODATION: 62 ACCESSIBLE COLLEGE ELITE SCHOOL SUCCESS STORIES 64 COLLEGE TECH 101 38 FINDING YOUR FUTURE 40 ACCESS TO STUDY ABROAD PROGRAMS 42 BEYOND THE ADA Cover Photo by Kerri Lane/PushLiving Photos WHEELS ON CAMPUS CONTRIBUTORS Tim Gilmer, project Actor, writer and A spinal cord injury put While attending the A frequent contributor editor of Wheels on advocate for the Derek Mortland on University of California to New Mobility, Linda Campus, graduated with inclusion of performers the path of therapeutic and earning a bachelor’s Mastandrea earned a bachelor’s from UCLA with disabilities in the recreation. Working with in human geography her bachelor’s from in the late 1960s, added entertainment industry, the Columbus Recreation and a master’s in public the University of a master’s from Southern Teal Sherer is best and Parks Department, policy, Alex Ghenis, Illinois in 1986 and Oregon University in 1977, known for creating the he gained expertise as an a C5-6 quadriplegic, her Juris Doctor from taught writing classes in award-winning online ADA accessible guidelines focused on how people Chicago-Kent College Portland for 12 years, then comedy series, My specialist working with with disabilities will be of Law in 1994. -

There's a Lot to Explore In

of the Corps CrossroadsThe Magazine of the Marines’ Memorial Association & Foundation, San Francisco \ SPRING 2019 Conservatory of Flowers Golden Gate Park THERE’S A LOT TO EXPLORE IN SAN FRANCISCO THIS SPRING. HONOR. COURAGE. COMMITMENT. Become a Recurring Monthly Donor! Our monthly donors are the guardians of our programs and services here at the Marines’ Memorial. They provide the steady, reliable funding that allows us to Commemorate, Educate and Serve our heroes every day of the year. $10/Month $20/Month $100/Month Provide a care Fund a Sponsor a Gold package for commemorative Star Parent to an Active Duty or educational attend our Honor service member event. and Remembrance overseas. event. ORIAL EM FO M U ’ N S D E A N T I I MARINES’ R O A N M MEMORIAL 2015 ASSOCIATION & FOUNDATION GIVE ONLINE at www.ourmission.MarinesMemorial.org/recurring or use the envelope at the center of this magazine and let us know you would like it to be monthly! Donations of $500 or more will be listed in Crossroads. If your giving is restricted to 501(c)3 organizations, please consider a gift to the Marines’ Memorial Foundation. of the Corps CrossroadsSPRING 2019 \ VOLUME 85 NUMBER 1 4 Correspondence 5 Bits & Pieces: News You Can Use 23 The Club Calendar EVENTS IN REVIEW MARINES’ MEMORIAL ASSOCIATION \ A NON-PROFIT VETERANS ORGANIZATION 609 Sutter St. · San Francisco, CA 94102 · tel (415) 673-6672 · fax (415) 441-3649 10 14th Gold Star Parents Event email [email protected] · website MarinesMemorial.org Room Reservations: 1-800-5-MARINE MarinesMemorial.org 14 Stopping Economic Espionage Crossroads of the Corps is published quarterly for Members and Supporters of the Marines’ Memorial Association and Foundation. -

College of Wooster Miscellaneous Materials: a Finding Tool

College of Wooster Miscellaneous Materials: A Finding Tool Denise Monbarren August 2021 Box 1 #GIVING TUESDAY Correspondence [about] #GIVINGWOODAY X-Refs. Correspondence [about] Flyers, Pamphlets See also Oversized location #J20 Flyers, Pamphlets #METOO X-Refs. #ONEWOO X-Refs #SCHOLARSTRIKE Correspondence [about] #WAYNECOUNTYFAIRFORALL Clippings [about] #WOOGIVING DAY X-Refs. #WOOSTERHOMEFORALL Correspondence [about] #WOOTALKS X-Refs. Flyers, Pamphlets See Oversized location A. H. GOULD COLLECTION OF NAVAJO WEAVINGS X-Refs. A. L. I. C. E. (ALERT LOCKDOWN INFORM COUNTER EVACUATE) X-Refs. Correspondence [about] ABATE, GREG X-Refs. Flyers, Pamphlets See Oversized location ABBEY, PAUL X-Refs. ABDO, JIM X-Refs. ABDUL-JABBAR, KAREEM X-Refs. Clippings [about] Correspondence [about] Flyers, Pamphlets See Oversized location Press Releases ABHIRAMI See KUMAR, DIVYA ABLE/ESOL X-Refs. ABLOVATSKI, ELIZA X-Refs. ABM INDUSTRIES X-Refs. ABOLITIONISTS X-Refs. ABORTION X-Refs. ABRAHAM LINCOLN MEMORIAL SCHOLARSHIP See also: TRUSTEES—Kendall, Paul X-Refs. Photographs (Proof sheets) [of] ABRAHAM, NEAL B. X-Refs. ABRAHAM, SPENCER X-Refs. Clippings [about] Correspondence [about] Flyers, Pamphlets ABRAHAMSON, EDWIN W. X-Refs. ABSMATERIALS X-Refs. Clippings [about] Press Releases Web Pages ABU AWWAD, SHADI X-Refs. Clippings [about] Correspondence [about] ABU-JAMAL, MUMIA X-Refs. Flyers, Pamphlets ABUSROUR, ABDELKATTAH Flyers, Pamphlets ACADEMIC AFFAIRS COMMITTEE X-Refs. ACADEMIC FREEDOM AND TENURE X-Refs. Statements ACADEMIC PROGRAMMING PLANNING COMMITTEE X-Refs. Correspondence [about] ACADEMIC STANDARDS COMMITTEE X-Refs. ACADEMIC STANDING X-Refs. ACADEMY OF AMERICAN POETRY PRIZE X-Refs. ACADEMY SINGERS X-Refs. ACCESS MEMORY Flyers, Pamphlets ACEY, TAALAM X-Refs. Flyers, Pamphlets ACKLEY, MARTY Flyers, Pamphlets ACLU Flyers, Pamphlets Web Pages ACRES, HENRY Clippings [about] ACT NOW TO STOP WAR AND END RACISM X-Refs.