Situating Dalits in Indian Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eating-In-Delhi

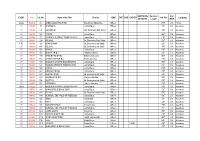

S No. Premises Name Premises Address District 1 DOMINOS PIZZA INDIA LTD GF, 18/27-E, EAST PATEL NAGAR, ND CENTRAL DISTRICT 2 STANDARD DHABA X-69 WEST PATEL NAGAR NEW DELHI CENTRAL DISTRICT 3 KALA DA TEA & SNACKS 26/140, WEST PATEL NAGAR, NEW DELHI CENTRAL DISTRICT 4 SHARON DI HATTI SHOP NO- 29, MALA MKT. WEST PATEL NAGAR NEW CENTRAL DISTRICT DELHI 5 MAA BHAGWATI RESTAURANT 3504, DARIBA PAN, DBG ROAD, DELHI CENTRAL DISTRICT 6 MITRA DA DHABA X-57, WEST PATEL NAGAR NEW DELHI CENTRAL DISTRICT 7 CHICKEN HUT 3181, SANGTRASHAN STREET PAHAR GANJ, NEW CENTRAL DISTRICT DELHI 8 DIMPLE RESTAURANT 2105,D.B.GUPTA ROAD KAROL BAGH NEW DELHI CENTRAL DISTRICT 9 MIGLANI DHABA 4240 GALI KRISHNA PAHAR GANJ, NEW DELHI CENTRAL DISTRICT 10 DURGA SNACKS 813,G.F. KAMRA BANGASH DARYA GANJ NEW DELHI- CENTRAL DISTRICT 10002 11 M/S SHRI SHYAM CATERERS GF, SHOP NO 74-76A, MARUTI JAGGANATH NEAR CENTRAL DISTRICT KOTWALI, NEAR POLICE STATION, OPPOSITE TRAFFIC SIGNAL, DAR 12 AROMA SPICE 15A/61, WEA KAROL BAGH, NEW DELHI CENTRAL DISTRICT 13 REPUBLIC OF CHICKEN 25/6, SHOP NO-4, GF, EAST PATEL NAGAR,DELHI CENTRAL DISTRICT 14 REHMATULLA DHABA 105/106/107/110 BAZAR MATIYA MAHAL, JAMA CENTRAL DISTRICT MASJID, DELHI 15 M/S LOCHIS CHIC BITES GF, SHOP NO 7724, PLOT NO 1, NEW MARKET KAROL CENTRAL DISTRICT BAGH, NEW DELHI 16 NEW MADHUR RESTAURANT 26/25-26 OLD RAJENDER NAGAR NEW DELHI CENTRAL DISTRICT 17 A B ENTERPRISES( 40 SEATS) 57/13,GF,OLD RAJINDER,NAGAR,DELHI CENTRAL DISTRICT 18 GRAND MADRAS CAFE GF,8301,GALI NO-4,MULTANI DHANDA PAHAR CENTRAL DISTRICT GANJ,DELHI-55 19 STANDARD SWEETS 3510,CHAWRI BAZAR,DELHI CENTRAL DISTRICT 20 M/S CAFE COFFEE DAY 3631, GROUND FLOOR, NETAJI SUBASH MARG, CENTRAL DISTRICT DARYAGANJ, NEW DELHI 21 CHANGEGI EATING HOUSE 3A EAST PARK RD KAROL BAGH ND DELHI 110055 CENTRAL DISTRICT 22 KAKE DA DHABA SHOP NO.47,OLD RAJINDER NAGAR,MARKET,NEW CENTRAL DISTRICT DELHI 23 CHOPRA DHABA 7A/5 WEA CHANNA MKT. -

Movie Aquisitions in 2010 - Hindi Cinema

Movie Aquisitions in 2010 - Hindi Cinema CISCA thanks Professor Nirmal Kumar of Sri Venkateshwara Collega and Meghnath Bhattacharya of AKHRA Ranchi for great assistance in bringing the films to Aarhus. For questions regarding these acquisitions please contact CISCA at [email protected] (Listed by title) Aamir Aandhi Directed by Rajkumar Gupta Directed by Gulzar Produced by Ronnie Screwvala Produced by J. Om Prakash, Gulzar 2008 1975 UTV Spotboy Motion Pictures Filmyug PVT Ltd. Aar Paar Chak De India Directed and produced by Guru Dutt Directed by Shimit Amin 1954 Produced by Aditya Chopra/Yash Chopra Guru Dutt Production 2007 Yash Raj Films Amar Akbar Anthony Anwar Directed and produced by Manmohan Desai Directed by Manish Jha 1977 Produced by Rajesh Singh Hirawat Jain and Company 2007 Dayal Creations Pvt. Ltd. Aparajito (The Unvanquished) Awara Directed and produced by Satyajit Raj Produced and directed by Raj Kapoor 1956 1951 Epic Productions R.K. Films Ltd. Black Bobby Directed and produced by Sanjay Leela Bhansali Directed and produced by Raj Kapoor 2005 1973 Yash Raj Films R.K. Films Ltd. Border Charulata (The Lonely Wife) Directed and produced by J.P. Dutta Directed by Satyajit Raj 1997 1964 J.P. Films RDB Productions Chaudhvin ka Chand Dev D Directed by Mohammed Sadiq Directed by Anurag Kashyap Produced by Guru Dutt Produced by UTV Spotboy, Bindass 1960 2009 Guru Dutt Production UTV Motion Pictures, UTV Spot Boy Devdas Devdas Directed and Produced by Bimal Roy Directed and produced by Sanjay Leela Bhansali 1955 2002 Bimal Roy Productions -

“Low” Caste Women in India

Open Cultural Studies 2018; 2: 735-745 Research Article Jyoti Atwal* Embodiment of Untouchability: Cinematic Representations of the “Low” Caste Women in India https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2018-0066 Received May 3, 2018; accepted December 7, 2018 Abstract: Ironically, feudal relations and embedded caste based gender exploitation remained intact in a free and democratic India in the post-1947 period. I argue that subaltern is not a static category in India. This article takes up three different kinds of genre/representations of “low” caste women in Indian cinema to underline the significance of evolving new methodologies to understand Black (“low” caste) feminism in India. In terms of national significance, Acchyut Kanya represents the ambitious liberal reformist State that saw its culmination in the constitution of India where inclusion and equality were promised to all. The movie Ankur represents the failure of the state to live up to the postcolonial promise of equality and development for all. The third movie, Bandit Queen represents feminine anger of the violated body of a “low” caste woman in rural India. From a dacoit, Phoolan transforms into a constitutionalist to speak about social justice. This indicates faith in Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s India and in the struggle for legal rights rather than armed insurrection. The main challenge of writing “low” caste women’s histories is that in the Indian feminist circles, the discourse slides into salvaging the pain rather than exploring and studying anger. Keywords: Indian cinema, “low” caste feminism, Bandit Queen, Black feminism By the late nineteenth century due to certain legal and socio-religious reforms,1 space of the Indian family had been opened to public scrutiny. -

School of Journalism and Mass Communication

SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION L.N.C.T UNIVERSITY BHOPAL MJMC- IV Semester Syllabus/Scheme S. No SUBJECTS THEORY PRACTICAL INTERNAL Film Studies 1. 80 20 (MJMC 401) Environment Journalism 2. 80 20 (MJMC 402) New Media & Digital 3. Journalism 80 20 (MJMC 403) Research Methodology 4. 80 20 (MJMC 404) Project-Viva 5. 100 (MJMC 405) L NCT UNIVERSITY, BHOPAL Programme: MJMC Semester – IV Session – Name of Paper Paper Code Theory FILM STUDIES MJMC 401 L T EST CAT Total 3 1 80 20 100 S. No Units / Topic Hours/Week Introduction to Film Journalism History of Film Journalism 1 Development of Film Journalism in India 4 hrs/week Major/Prominent Critiques Relationship between Cinema & Society Various forms of Cinema Development of Cinema Brief History of World Cinema-Pre Cinema Machines,Silent Era to 4 hrs/week 2 Early Talkies,Big Studios(Paramount,Disney,Warnes Bros,2Oth Century Fox), Changes occurred in Cinema Early Indian Cinema-Heeralal Sen, Dhundi Ji Phalke, Ardeshi Irani, Silent, Primitive & Pioneers, Reference Film-Raja Harishchandra & Alam Ara Emergence of Film Studio-New Theatres, Bombay Talkies, Imperial Theatre, R. K Studio Art Cinema of India-Bhuvan Shome, Uski Roti, Mirch Masala, Neecha Nagar, Mother India, Pather Panchali, Do Bigha Zameen Cinema in Digital Era-Changes of theme in Cinema, Reference Film, Raavan, Krish 3 & Baahubali Understanding Cinema Understanding Cinema/Genres of Film, Cultural Significance in relation to 3 4 hrs/week Film, Film Screening Story Telling Techniques of Cinema-Elements of Story -

Portrayal of Women in the Popular Indian Cinema Wizerunek Kobiet W

Portrayal of Women in the Popular Indian Cinema Wizerunek kobiet w popularnym kinie indyjskim Sharaf Rehman THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS – RIO GRANDE VALLEY, USA Keywords Indian cinema, women, stereotyping Słowa klucze kino indyjskie, kobiety, stereotypy Abstract Popular Indian cinema is primarily rooted in formulaic narrative structure relying heavily on stereotypes. However, in addition to having been the only true “mass medium” in India, the movies have provided more than escapist fantasy and entertainment fare. Indian popular cinema has actively engaged in social and political criticism, promoted certain political ideologies, and reinforced In- dian cultural and social values. This paper offers a brief introduction to the social role of the Indian cinema in its culture and proceeds to analyze the phenomenon of stereotyping of women in six particular roles. These roles being: the mother, the wife, the daughter, the daughter-in-law, the widow, and “the other woman”. From the 1940s when India was fighting for her independence, to the present decade where she is emerging as a major future economy, Indian cinema has Artykuły i rozprawy shifted in its representation and stereotyping of women. This paper traces these shifts through a textual analysis of seven of the most popular Indian movies of the past seven decades. Abstrakt Popularne kino indyjskie jest przede wszystkim wpisane w schematyczną strukturę narracyjną. Mimo, że jest to tak naprawdę jedyne „medium masowe” w Indiach, tamtejsze kino to coś więcej niż rozrywka i eskapistyczne fantazje. Kino indyjskie angażuje się w krytykę społeczną i polityczną, promuje pewne Portrayal of Women in the Popular Indian Cinema 157 ideologie a także umacnia indyjskie kulturowe i społeczne wartości. -

Smita Patil: Fiercely Feminine

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2017 Smita Patil: Fiercely Feminine Lakshmi Ramanathan The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2227 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SMITA PATIL: FIERCELY FEMININE BY LAKSHMI RAMANATHAN A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2017 i © 2017 LAKSHMI RAMANATHAN All Rights Reserved ii SMITA PATIL: FIERCELY FEMININE by Lakshmi Ramanathan This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts. _________________ ____________________________ Date Giancarlo Lombardi Thesis Advisor __________________ _____________________________ Date Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Acting Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT SMITA PATIL: FIERCELY FEMININE by Lakshmi Ramanathan Advisor: Giancarlo Lombardi Smita Patil is an Indian actress who worked in films for a twelve year period between 1974 and 1986, during which time she established herself as one of the powerhouses of the Parallel Cinema movement in the country. She was discovered by none other than Shyam Benegal, a pioneering film-maker himself. She started with a supporting role in Nishant, and never looked back, growing into her own from one remarkable performance to the next. -

375 © the Author(S) 2019 S. Sengupta Et Al. (Eds.), 'Bad' Women

INDEX1 A Anti-Sikh riots, 242, 243, 249 Aarti, 54 Apsaras, 13, 95–97, 100, 105 Achhut Kanya, 30, 31, 37 Aranyer Din Ratri, 143 Actress, 9, 18, 45n1, 54, 67, 88, 109, Armed Forces Special Powers Act, 170, 187, 213, 269, 342, 347–362, 255, 255n24 365–367, 369, 372, 373 Astitva, 69 Adalat, 115, 203 Atankvadi, 241–256 Akhir Kyon, 69 Azmi, Shabana, 54, 68 Akhtar, Farhan, 307, 317n13 Alvi, Abrar, 60 Ambedkar, B.R., 31, 279n2 B Ameeta, 135 Babri Masjid, 156, 160 Amrapali, 93–109, 125 Bachchan, Amitabh, 67, 203, 204, Amu, 243–249 210, 218 Anaarkali of Aarah, 365, 367, 370, 373 Bagbaan, 69 Anand, Dev, 7n25, 8n27, 64 Bahl, Mohnish, 300 Anarkali, 116, 368–369 Bandini, 18, 126, 187–199 Andarmahal, 49, 53 Bandit Queen, 223–237 Andaz, 277–293 Bar dancer, 151 Angry Young Man, 67, 203–205, 208, Barjatya, Sooraj, 297, 300, 373 218, 219 Basu Bhattacharya, 348, 355 Ankush, 69 Basu, Bipasha, 88 1 Note: Page numbers followed by ‘n’ refer to notes. © The Author(s) 2019 375 S. Sengupta et al. (eds.), ‘Bad’ Women of Bombay Films, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26788-9 376 INDEX Bedi, Bobby, 232–235 237, 261, 266–268, 278, 279, Benaras, 333, 334 283, 283n8, 285, 291, 318, 332, Benegal, Shyam, 7n23, 11, 11n35, 13, 334, 335, 338, 343, 350, 351, 13n47, 68, 172n9, 348, 351, 366 355, 356, 359, 361, 372n3 Beshya/baiji, 48, 49, 55, 56 Central Board of Film Certification Bhaduri, Jaya, 209, 218 (CBFC), 224, 246, 335, Bhagwad Gita, 301 335n1, 336 Bhakti, 95, 98, 99, 101, 191n11, 195, Chak De! India, 70 195n18, 196 Chameli, 179–181 Bhakti movement, 320 Chastity, 82, -

LALITHA GOPALAN Fall 2010 EMPLOYMENT

LALITHA GOPALAN Fall 2010 EMPLOYMENT Associate Professor, Department of Radio-Television –Film and Department of Asian Studies, University of Texas at Austin, Fall 2007-present. Visiting Associate Professor, Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures, University of California, Berkeley, Spring 2009. Associate Professor, School of Foreign Service and Department of English, Georgetown University, 2002-07. Assistant Professor, School of Foreign Service and Department of English, Georgetown University, 1992-2002. EDUCATION Ph.D. University of Rochester. 1993. Comparative Literature Program, Department of Foreign Languages, Literatures, and Linguistics. M.A. (Anthropology) University of Rochester, 1986 M.A. (Sociology) Delhi School of Economics, 1984 B.A. (Economics) Madras Christian College, 1982 PUBLICATIONS BOOKS 24 Frames: Indian Cinema. Edited. London: Wallflower Press, 2010. Bombay. BFI Modern Classics. London: British Film Institute. December 2005. Cinema of Interruptions: Action Genres in Contemporary Indian Cinema. London: British Film Institute. 2002. (Indian Reprint Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2002) 2 ARTICLES AND ESSAYS ‘Introduction.’ 24 Frames: Indian Cinema. London: Wallflower Press. Ed. Lalitha Gopalan. London: Wallflower Press, 2010. ‘Film Culture in Chennai.’ Film Quarterly, Volume 62.1 (Fall 2008). ‘Indian Cinema.’ In An Introduction to Film Studies. Ed. Jill Nelmes. 4th Edition. London: Routledge. 2006. (Revised and expanded version of the essay published in the 3rd Edition, 2003) ‘Avenging Women in Indian Cinema.’ Screen. 38.1 (Spring 1997): 42-59. Screen Award for the Best Article submitted in 1996. ‘Coitus Interruptus and the Love Story in Indian Cinema.’ Representing the Body: Gender Issues in India's Art. Ed. Vidya Dehejia. New Delhi: Kali for Women, 1997. 124-139. ‘Putting Asunder: Fassbinder and The Marriage of Maria Braun.’ Deep Focus January 1989: 50- 57. -

Utopia in Bollywood: 'Hum Aapke Hain Koun...!' Author(S): Rustom Bharucha Source: Economic and Political Weekly, Vol

Utopia in Bollywood: 'Hum Aapke Hain Koun...!' Author(s): Rustom Bharucha Source: Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 30, No. 15 (Apr. 15, 1995), pp. 801-804 Published by: Economic and Political Weekly Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4402626 . Accessed: 14/01/2015 09:57 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Economic and Political Weekly is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Economic and Political Weekly. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 140.233.70.45 on Wed, 14 Jan 2015 09:57:20 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions PERSPECTIVES appears to transcend. If this were so. Utopia in Bollywood entertainment could be reduced to an essentialised, a historical set of categories, 'Hum Aapke Ham Koun...!' conventions and formulae that could be perpetuatedthrough skill alone. But this is Rustom Bharucha not the case, since the worldof entertainment had different significances at different It is sad that we should be celebrating the centuryof cinema in India points in time. There are different kinds of with aI superhit so vacuious as 'Hum Aapke Hain Koun... ", a film devoid entertainment,different 'treatments'of the of any illusion worthyof thlecondition of the millions of people who are same rhetoric,different ways of envisioning utopia.These differneces. -

EVENT Year Lib. No. Name of the Film Director 35MM DCP BRD DVD/CD Sub-Title Language BETA/DVC Lenght B&W Gujrat Festival 553 ANDHA DIGANTHA (P

UMATIC/DG Duration/ Col./ EVENT Year Lib. No. Name of the Film Director 35MM DCP BRD DVD/CD Sub-Title Language BETA/DVC Lenght B&W Gujrat Festival 553 ANDHA DIGANTHA (P. B.) Man Mohan Mahapatra 06Reels HST Col. Oriya I. P. 1982-83 73 APAROOPA Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1985-86 201 AGNISNAAN DR. Bhabendra Nath Saikia 09Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1986-87 242 PAPORI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 252 HALODHIA CHORAYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1988-89 294 KOLAHAL Dr. Bhabendra Nath Saikia 06Reels EST Col. Assamese F.O.I. 1985-86 429 AGANISNAAN Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 09Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1988-89 440 KOLAHAL Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 06Reels SST Col. Assamese I. P. 1989-90 450 BANANI Jahnu Barua 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 483 ADAJYA (P. B.) Satwana Bardoloi 05Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 494 RAAG BIRAG (P. B.) Bidyut Chakravarty 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 500 HASTIR KANYA(P. B.) Prabin Hazarika 03Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 509 HALODHIA CHORYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 522 HALODIA CHORAYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels FST Col. Assamese I. P. 1990-91 574 BANANI Jahnu Barua 12Reels HST Col. Assamese I. P. 1991-92 660 FIRINGOTI (P. B.) Jahnu Barua 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1992-93 692 SAROTHI (P. B.) Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 05Reels EST Col. -

Confessions of a Red Thread Bandit Queen: Ten Years of Fieldwork with Narrative Embroidery

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2006 Confessions of a Red Thread Bandit Queen: Ten Years of Fieldwork with Narrative Embroidery Skye Morrison [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Morrison, Skye, "Confessions of a Red Thread Bandit Queen: Ten Years of Fieldwork with Narrative Embroidery" (2006). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 317. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/317 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Confessions of a Red Thread Bandit Queen: Ten Years of Fieldwork with Narrative Embroidery Skye Morrison Ph.D. PO Box 517, Hastings, Ontario, Canada, KOL 1YO [email protected] Photos: Dr. Skye Morrison or her archive, by permission To quote the great weaver and poet Kabir, Do away with the bark, Get hold of the pith Then you’ll contemplate, Infinite treasures1 I confess to living a life full of unexpected experiences trying to remove the bark from the tree of commercialism and finding the ever-fruitful world of contemporary textiles made by traditional artisans. This presentation is a series of confessions brought to light through fieldwork, teaching and working in India and Canada / there and here / two worlds made into one. We begin with the six images connected to confessions or thoughts to live by: Figure 1. -

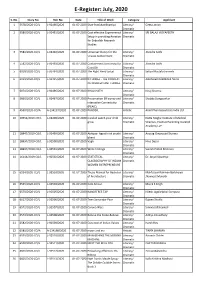

E-Register: July, 2020

E-Register: July, 2020 S. No. Diary No. RoC No. Date Title of Work Category Applicant 1 5578/2020-CO/L L-92490/2020 01-07-2020 Shat-Pratishat Bhartiya Literary/ Geeta Atrish Dramatic 2 5580/2020-CO/L L-92491/2020 01-07-2020 Cost effective Experimental Literary/ SRI BALAJI VIDYAPEETH Setup in providing Aeration Dramatic for Zebrafish Research Studies 3 5581/2020-CO/L L-92492/2020 01-07-2020 Universal theory for the Literary/ Jitendra Sethi viruses containment Dramatic 4 5582/2020-CO/L L-92493/2020 01-07-2020 Containment tomorrow for Literary/ Jitendra Sethi Covid19 Dramatic 5 6018/2020-CO/L L-92494/2020 01-07-2020 The Right Hand to Eat Literary/ Safiya Mustafa Jariwala Dramatic 6 6019/2020-CO/L L-92495/2020 01-07-2020 D TUNNEL - THE CONCEPT Literary/ ABHISHEK RABINDER NATH OF DISINFECTANT TUNNEL Dramatic 7 6071/2020-CO/L L-92496/2020 01-07-2020 KHALI HATH Literary/ Niraj Sharma Dramatic 8 5860/2020-CO/L L-92497/2020 01-07-2020 Preservation Efficiency and Literary/ Shabda Dongaonkar interactive Connectivity Dramatic (PEAIC) 9 4530/2020-CO/A A-134197/2020 01-07-2020 PURODIL Artistic Aimil Pharmaceuticals India Ltd. 10 20554/2019-CO/L L-92498/2020 01-07-2020 icarekid watch your child Literary/ Datta Meghe Institute of Medical grow Dramatic Sciences ,Positive Parenting iCareKid Academy LLP 11 18947/2019-CO/L L-92499/2020 01-07-2020 Abhipsa- Agyat ki ek anuthi Literary/ Anurag Omprasad Sharma bhent Dramatic 12 18937/2019-CO/L L-92500/2020 01-07-2020 Vagh Literary/ Hina Desai Dramatic 13 18917/2019-CO/L L-92501/2020 01-07-2020 Write Feelings Literary/ Suresh Pattali Krishnan Dramatic 14 16114/2019-CO/L L-92502/2020 01-07-2020 STATISTICAL Literary/ Dr.