Some Reflections on Existentialism in Relation to Law Anthony R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life Without Meaning? Richard Norman

17 Life Without Meaning? Richard Norman The Alpha Course, a well‐known evangelical Christian programme, advertises itself with posters displaying the words THE MEANING OF LIFE IS_________, followed by the invitation ‘Fill in the blanks at alpha.org’. Followers of the course will discover that ‘Men and women were created to live in a relationship with God’, and that ‘without that relationship there will always be a hunger, an emptiness, a feeling that something is missing’.1 We all have that need because we are all sinners, we are told, and the truth which will fill the need is that Jesus Christ died to save us from our sins. Not all Christian or other religious views about the meaning of life are as simplistic as this, but they typically share the assumptions that the meaning of life is to be found in some belief whose truth we need to recognize, and that this is a belief about the purpose for which we exist. A further implication is that this purpose is the purpose intended by the God who created us, and that if we fail to identify and live in accordance with that purpose, our lives will lack meaning. The assumption is echoed in the question many humanists will have encountered: if you don’t believe in a God, what’s the point of it all? And many people who don’t share the answer still accept the legitimacy of the question – ‘What is the meaning of life?’ – and assume that what we need is a correct belief, religious or non‐religious, which will fill the blank in the sentence ‘The meaning of life is …’. -

Philosophical Theory-Construction and the Self-Image of Philosophy

Open Journal of Philosophy, 2014, 4, 231-243 Published Online August 2014 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojpp http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojpp.2014.43031 Philosophical Theory-Construction and the Self-Image of Philosophy Niels Skovgaard Olsen Department of Philosophy, University of Konstanz, Konstanz, Germany Email: [email protected] Received 25 May 2014; revised 28 June 2014; accepted 10 July 2014 Copyright © 2014 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract This article takes its point of departure in a criticism of the views on meta-philosophy of P.M.S. Hacker for being too dismissive of the possibility of philosophical theory-construction. But its real aim is to put forward an explanatory hypothesis for the lack of a body of established truths and universal research programs in philosophy along with the outline of a positive account of what philosophical theories are and of how to assess them. A corollary of the present account is that it allows us to account for the objective dimension of philosophical discourse without taking re- course to the problematic idea of there being worldly facts that function as truth-makers for phi- losophical claims. Keywords Meta-Philosophy, Hacker, Williamson, Philosophical Theories 1. Introduction The aim of this article is to use a critical discussion of the self-image of philosophy presented by P. M. S. Hacker as a platform for presenting an alternative, which offers an account of how to think about the purpose and cha- racter of philosophical theories. -

The Relativism of Blame and Williams' Relativism of Distance

ABSTRACT: Bernard Williams is a sceptic about the objectivity of moral value, embracing instead a certain qualified moral relativism—the ‘relativism of distance’. His attitude to blame too is in part sceptical (he thought it often involved a certain ‘fantasy’). I will argue that the relativism of distance is unconvincing, even incoherent; but also that it is detachable from the rest of Williams’ moral philosophy. I will then go on to propose an entirely localized thesis I call the relativism of blame, which says that when an agent’s moral shortcomings by our lights are a matter of their living according to the moral thinking of their day, judgements of blame are out of order. Finally, I will propose a form of moral judgement we may sometimes quite properly direct towards historically distant agents when blame is inappropriate—moral-epistemic disappointment. Together these two proposals may help release us from the grip of the idea that moral appraisal always involves the potential applicability of blame, and so from a key source of the relativist idea that moral appraisal is inappropriate over distance. The Relativism of Blame and Williams’ Relativism of Distance Must I think of myself as visiting in judgement all the reaches of history? Of course, one can imagine oneself as Kant at the court of King Arthur, disapproving of its injustices, but exactly what grip does this get on one’s ethical or political thought?1 Bernard Williams famously argued for a distinctive brand of moral relativism, which he regarded as capturing the truth in relativism, and which he called the relativism of distance. -

The Return of Vitalism: Canguilhem and French Biophilosophy in the 1960S

The Return of Vitalism: Canguilhem and French Biophilosophy in the 1960s Charles T. Wolfe Unit for History and Philosophy of Science University of Sydney [email protected] Abstract The eminent French biologist and historian of biology, François Jacob, once notoriously declared ―On n‘interroge plus la vie dans les laboratoires‖1: laboratory research no longer inquires into the notion of ‗Life‘. Nowadays, as David Hull puts it, ―both scientists and philosophers take ontological reduction for granted… Organisms are ‗nothing but‘ atoms, and that is that.‖2 In the mid-twentieth century, from the immediate post-war period to the late 1960s, French philosophers of science such as Georges Canguilhem, Raymond Ruyer and Gilbert Simondon returned to Jacob‘s statement with an odd kind of pathos: they were determined to reverse course. Not by imposing a different kind of research program in laboratories, but by an unusual combination of historical and philosophical inquiry into the foundations of the life sciences (particularly medicine, physiology and the cluster of activities that were termed ‗biology‘ in the early 1800s). Even in as straightforwardly scholarly a work as La formation du concept de réflexe aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles (1955), Canguilhem speaks oddly of ―defending vitalist biology,‖ and declares that Life cannot be grasped by logic (or at least, ―la vie déconcerte la logique‖). Was all this historical and philosophical work merely a reassertion of ‗mysterian‘, magical vitalism? In order to answer this question we need to achieve some perspective on Canguilhem‘s ‗vitalism‘, notably with respect to its philosophical influences such as Kurt Goldstein. -

On the Coherence of Sartre's Defense of Existentialism Against The

Untitled 7/12/05 3:41 PM On the Coherence of Sartre’s Defense of Existentialism Against the Essentialist Charge of Ethical Relativism in His “Existentialism and Humanism” Brad Cherry I.Introduction Although its slim volume may suggest otherwise, Jean-Paul Sartre’s “Existentialism and Humanism” treats a wealth of existentialist themes. Indeed, within its pages, Sartre characterizes many of the hallmarks of existentialist thought, including subjectivity, freedom, responsibility, anguish, forlornness, despair, and so on. Perhaps most importantly, however, Sartre’s “Existentialism and Humanism” occasions a defense of existentialism against its most frequently dealt criticisms, particularly the essentialist charge that existentialism necessarily gives rise to ethical relativism. And while this defense may seem convincing at first, in many places, it also seems to abandon, for the sake of its project, the fundamental commitments of existentialism, at least as Sartre understands them. Thus, in this essay, I critically examine the coherence of Sartre’s defense of existentialism against the essentialist charge of ethical relativism. To the extent that that defense relies largely upon his espousal of an existentialist ethics, I examine, in particular, whether that ethics coheres with the fundamental commitments of existentialism as he understands them. Following this examination, I conclude that (a) the fundamental commitments of existentialism preclude Sartre from coherently positing objectively valid normative ethical statements, that (b) because he nonetheless posits such statements in his espousal of an existentialist ethics, his defense of existentialism against the essentialist charge of ethical relativism breaks down, and finally, that (c) although this incoherence presents a substantial problem for Sartre, one may still defend his attempt to espouse an existentialist ethics. -

God As Both Ideal and Real Being in the Aristotelian Metaphysics

God As Both Ideal and Real Being In the Aristotelian Metaphysics Martin J. Henn St. Mary College Aristotle asserts in Metaphysics r, 1003a21ff. that "there exists a science which theorizes on Being insofar as Being, and on those attributes which belong to it in virtue of its own nature."' In order that we may discover the nature of Being Aristotle tells us that we must first recognize that the term "Being" is spoken in many ways, but always in relation to a certain unitary nature, and not homonymously (cf. Met. r, 1003a33-4). Beings share the same name "eovta," yet they are not homonyms, for their Being is one and the same, not manifold and diverse. Nor are beings synonyms, for synonymy is sameness of name among things belonging to the same genus (as, say, a man and an ox are both called "animal"), and Being is no genus. Furthermore, synonyms are things sharing a common intrinsic nature. But things are called "beings" precisely because they share a common relation to some one extrinsic nature. Thus, beings are neither homonyms nor synonyms, yet their core essence, i.e. their Being as such, is one and the same. Thus, the unitary Being of beings must rest in some unifying nature extrinsic to their respective specific essences. Aristotle's dialectical investigations into Being eventually lead us to this extrinsic nature in Book A, i.e. to God, the primary Essence beyond all specific essences. In the pre-lambda books of the Metaphysics, however, this extrinsic nature remains very much up for grabs. -

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry Jaap van Brakel Abstract: In this paper I assess the relation between philosophy of chemistry and (general) philosophy of science, focusing on those themes in the philoso- phy of chemistry that may bring about major revisions or extensions of cur- rent philosophy of science. Three themes can claim to make a unique contri- bution to philosophy of science: first, the variety of materials in the (natural and artificial) world; second, extending the world by making new stuff; and, third, specific features of the relations between chemistry and physics. Keywords : philosophy of science, philosophy of chemistry, interdiscourse relations, making stuff, variety of substances . 1. Introduction Chemistry is unique and distinguishes itself from all other sciences, with respect to three broad issues: • A (variety of) stuff perspective, requiring conceptual analysis of the notion of stuff or material (Sections 4 and 5). • A making stuff perspective: the transformation of stuff by chemical reaction or phase transition (Section 6). • The pivotal role of the relations between chemistry and physics in connection with the question how everything fits together (Section 7). All themes in the philosophy of chemistry can be classified in one of these three clusters or make contributions to general philosophy of science that, as yet , are not particularly different from similar contributions from other sci- ences (Section 3). I do not exclude the possibility of there being more than three clusters of philosophical issues unique to philosophy of chemistry, but I am not aware of any as yet. Moreover, highlighting the issues discussed in Sections 5-7 does not mean that issues reviewed in Section 3 are less im- portant in revising the philosophy of science. -

Spiritual Ecology: on the Way to Ecological Existentialism

religions Article Spiritual Ecology: On the Way to Ecological Existentialism Sam Mickey Theology and Religious Studies, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, CA 94117, USA; [email protected] Received: 17 September 2020; Accepted: 29 October 2020; Published: 4 November 2020 Abstract: Spiritual ecology is closely related to inquiries into religion and ecology, religion and nature, and religious environmentalism. This article presents considerations of the unique possibilities afforded by the idea of spiritual ecology. On one hand, these possibilities include problematic tendencies in some strands of contemporary spirituality, including anti-intellectualism, a lack of sociopolitical engagement, and complicity in a sense of happiness that is captured by capitalist enclosures and consumerist desires. On the other hand, spiritual ecology promises to involve an existential commitment to solidarity with nonhumans, and it gestures toward ways of knowing and interacting that are more inclusive than what is typically conveyed by the term “religion.” Much work on spiritual ecology is broadly pluralistic, leaving open the question of how to discern the difference between better and worse forms of spiritual ecology. This article affirms that pluralism while also distinguishing between the anti-intellectual, individualistic, and capitalistic possibilities of spiritual ecology from varieties of spiritual ecology that are on the way to what can be described as ecological existentialism or coexistentialism. Keywords: spirituality; existentialism; ecology; animism; pluralism; knowledge 1. Introduction Spiritual ecology, broadly conceived, refers to ways that individuals and communities orient their thinking, feeling, and acting in response to the intersection of religions and spiritualities with ecology, nature, and environmentalism. There are other ways of referring to this topic. -

The Existentialism of Martin Buber and Implications for Education

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 69-4919 KINER, Edward David, 1939- THE EXISTENTIALISM OF MARTIN BUBER AND IMPLICATIONS FOR EDUCATION. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1968 Education, general University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE EXISTENTIALISM OF MARTIN BUBER AND IMPLICATIONS FOR EDUCATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Edward David Kiner, B.A., M.A. ####*### The Ohio State University 1968 Approved by Adviser College of Education This thesis is dedicated to significant others, to warm, vital, concerned people Who have meant much to me and have helped me achieve my self, To people whose lives and beings have manifested "glimpses" of the Eternal Thou, To my wife, Sharyn, and my children, Seth and Debra. VITA February 14* 1939 Born - Cleveland, Ohio 1961......... B.A. Western Reserve University April, 1965..... M.A. Hebrew Union College Jewish Institute of Religion June, 1965...... Ordained a Rabbi 1965-1968........ Assistant Rabbi, Temple Israel, Columbus, Ohio 1967-1968...... Director of Religious Education, Columbus, Ohio FIELDS OF STUDY Major Field: Philosophy of Education Studies in Philosophy of Education, Dr. Everett J. Kircher Studies in Curriculum, Dr. Alexander Frazier Studies in Philosophy, Dr. Marvin Fox ill TABLE OF CONTENTS Page DEDICATION............................................. ii VITA ................................................... iii INTRODUCTION............................ 1 Chapter I. AN INTRODUCTION TO MARTIN BUBER'S THOUGHT....... 6 Philosophical Anthropology I And Thou Martin Buber and Hasidism Buber and Existentialism Conclusion II. EPISTEMOLOGY . 30 Truth Past and Present I-It Knowledge Thinking Philosophy I-Thou Knowledge Complemented by I-It Living Truth Buber as an Ebdstentialist-Intuitionist Implications for Education A Major Problem Education, Inclusion, and the Problem of Criterion Conclusion III. -

History and Theory of Philosophy

FEDERAL STATE BUDGETARY EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTION OF HIGHER EDUCATION "BASHKIR STATE MEDICAL UNIVERSITY" OF THE MINISTRY OF HEALTHCARE OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION (FSBEI HE BSMU MOH Russia) HISTORY AND THEORY OF PHILOSOPHY Textbook Ufa 2020 1 UDC 1(09)(075.8) BBC 87.3я7 H90 Reviewers: Doctor of Philosophy, Professor, Head of the department «Social work» FSBEI HE «Bashkir State University» U.S. Vildanov Doctor of Philosophy, Professor at the Department of Philosophy and History FSBEIHE «Bashkir State Agricultural University» A.I. Stoletov History and theory of philosophy:textbook/ K.V. Khramova, H90 R.I. Devyatkina, Z.R. Sadikova, O.M. Ivanova, O.G. Afanasyeva, A.S. Zubairova-Valeeva, N.R. Mingazova, G.R. Davletshina — Ufa: Ufa: FSBEIHEBSMUMOHRussia, 2020. – 127 p. The manual was prepared in accordance with the requirements of the Federal State Educational Standard of Higher Education in specialty 31.05.01 «General Medicine» the current curriculum and on the basis of the work program on the discipline of philosophy. The manual is focused on the competence-based learning model. It has an original, uniform for all classes structure, including the topic, a summary of the training questions, the subject of essays, training materials, test items with response standards, recommended literature. This manual covers topics related to the periods of development of world philosophy. Designed for students in the specialty 31.05.01 «General Medicine». It is recommended to be published by the Coordinating Scientific and Methodological Council and was approved by the decision of the Editorial and Publishing Council of the BSMU of the Ministry of Healthcare of Russia. -

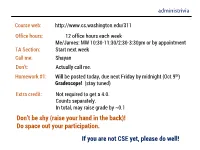

CSE Yet, Please Do Well! Logical Connectives

administrivia Course web: http://www.cs.washington.edu/311 Office hours: 12 office hours each week Me/James: MW 10:30-11:30/2:30-3:30pm or by appointment TA Section: Start next week Call me: Shayan Don’t: Actually call me. Homework #1: Will be posted today, due next Friday by midnight (Oct 9th) Gradescope! (stay tuned) Extra credit: Not required to get a 4.0. Counts separately. In total, may raise grade by ~0.1 Don’t be shy (raise your hand in the back)! Do space out your participation. If you are not CSE yet, please do well! logical connectives p q p q p p T T T T F T F F F T F T F NOT F F F AND p q p q p q p q T T T T T F T F T T F T F T T F T T F F F F F F OR XOR 푝 → 푞 • “If p, then q” is a promise: p q p q F F T • Whenever p is true, then q is true F T T • Ask “has the promise been broken” T F F T T T If it’s raining, then I have my umbrella. related implications • Implication: p q • Converse: q p • Contrapositive: q p • Inverse: p q How do these relate to each other? How to see this? 푝 ↔ 푞 • p iff q • p is equivalent to q • p implies q and q implies p p q p q Let’s think about fruits A fruit is an apple only if it is either red or green and a fruit is not red and green. -

Conditional Statement/Implication Converse and Contrapositive

Conditional Statement/Implication CSCI 1900 Discrete Structures •"ifp then q" • Denoted p ⇒ q – p is called the antecedent or hypothesis Conditional Statements – q is called the consequent or conclusion Reading: Kolman, Section 2.2 • Example: – p: I am hungry q: I will eat – p: It is snowing q: 3+5 = 8 CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 1 CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 2 Conditional Statement/Implication Truth Table Representing Implication (continued) • In English, we would assume a cause- • If viewed as a logic operation, p ⇒ q can only be and-effect relationship, i.e., the fact that p evaluated as false if p is true and q is false is true would force q to be true. • This does not say that p causes q • If “it is snowing,” then “3+5=8” is • Truth table meaningless in this regard since p has no p q p ⇒ q effect at all on q T T T • At this point it may be easiest to view the T F F operator “⇒” as a logic operationsimilar to F T T AND or OR (conjunction or disjunction). F F T CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 3 CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 4 Examples where p ⇒ q is viewed Converse and contrapositive as a logic operation •Ifp is false, then any q supports p ⇒ q is • The converse of p ⇒ q is the implication true. that q ⇒ p – False ⇒ True = True • The contrapositive of p ⇒ q is the –False⇒ False = True implication that ~q ⇒ ~p • If “2+2=5” then “I am the king of England” is true CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 5 CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 6 1 Converse and Contrapositive Equivalence or biconditional Example Example: What is the converse and •Ifp and q are statements, the compound contrapositive of p: "it is raining" and q: I statement p if and only if q is called an get wet? equivalence or biconditional – Implication: If it is raining, then I get wet.