Giswatch 2008 PDF.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Overview of Today's and Tomorrow's M- Commerce In

AN OVERVIEW OF TODAY’S AND TOMORROW’S M- COMMERCE IN THE NETHERLANDS AND EUROPE Hong-Vu Dang BMI Paper AN OVERVIEW OF TODAY’S AND TOMORROW’S M- COMMERCE IN THE NETHERLANDS AND EUROPE Hong-Vu Dang BMI Paper Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam Faculty of Sciences Business Mathematics and Informatics De Boelelaan 1081a 1081 HV Amsterdam www.few.vu.nl August 2006 PREFACE A part of the masters programme of the study that I am following, Business Mathematics & Informatics (BMI) at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, is writing a BMI paper. In this paper a problem in the field of BMI is assessed using existing literature. The subjects addressed in this paper are the past, present and future developments of the relatively new phenomenon called m-commerce. Developments discussed will be from a technological perspective as well as a business perspective. I would like to express my gratitude to Dr. S. Bhulai of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam for his guidance while I was writing this paper. Hong-Vu Dang BMI paper: An Overview Of Today’s And Tomorrow’s M-Commerce In The Netherlands And Europe ABSTRACT This paper explains: • What m-commerce is: in a nutshell, it is commerce using a mobile device such as a hand-held device or a smart phone; • What it is used for: currently, m-commerce in Europe mainly consists of messaging, such as SMS, and mobile entertainment (think of ringtones, wallpapers, and mobile games); • What technology is involved with m-commerce: this paper describes the history and future of mobile networks from 1G to 3G, and how other technologies can be used for m-commerce such as GPS, and Wi-Fi; • The business aspects of m-commerce: how much does it cost to enable m- commerce (for instance the costs of the European UMTS network) and how much turnover is made. -

International Benchmarking of Australian Telecommunications International Services Benchmarking

telecoms.qxd 9/03/99 10:06 AM Page 1 International Benchmarking of Australian Telecommunications International Services Benchmarking March 1999 Commonwealth of Australia 1999 ISBN 0 646 33589 8 This work is subject to copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, the work may be reproduced in whole or in part for study or training purposes, subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgment of the source. Reproduction for commercial use or sale requires prior written permission from AusInfo. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Manager, Legislative Services, AusInfo, GPO Box 1920, Canberra, ACT, 2601. Inquiries: Media and Publications Productivity Commission Locked Bag 2 Collins Street East Post Office Melbourne Vic 8003 Tel: (03) 9653 2244 Fax: (03) 9653 2303 Email: [email protected] An appropriate citation for this paper is: Productivity Commission 1999, International Benchmarking of Australian Telecommunications Services, Research Report, AusInfo, Melbourne, March. The Productivity Commission The Productivity Commission, an independent Commonwealth agency, is the Government’s principal review and advisory body on microeconomic policy and regulation. It conducts public inquiries and research into a broad range of economic and social issues affecting the welfare of Australians. The Commission’s independence is underpinned by an Act of Parliament. Its processes and outputs are open to public scrutiny and are driven by concern for the wellbeing of the community as a whole. Information on the Productivity Commission, its publications and its current work program can be found on the World Wide Web at www.pc.gov.au or by contacting Media and Publications on (03) 9653 2244. -

APPENDICES to the Evidence of Michael Piaskoski Rogers Communications Partnership

EB-2015-0141 Ontario Energy Board IN THE MATTER OF the Ontario Energy Board Act, 1998, S.O. 1998, c.15, (Schedule B); AND IN THE MATTER OF Decision EB-2013-0416/EB- 2014-0247 of the Ontario Energy Board (the “OEB”) issued March 12, 2015 approving distribution rates and charges for Hydro One Networks Inc. (“Hydro One”) for 2015 through 2017, including an increase to the Pole Access Charge; AND IN THE MATTER OF the Decision of the OEB issued April 17, 2015 setting the Pole Access Charge as interim rather than final; AND IN THE MATTER OF the Decision and Order issued June 30, 2015 by the OEB granting party status to Rogers Communications Partnership, Allstream Inc., Shaw Communications Inc., Cogeco Cable Inc., on behalf of itself and its affiliate, Cogeco Cable Canada LP, Quebecor Media, Bragg Communications, Packet-tel Corp., Niagara Regional Broadband Network, Tbaytel, Independent Telecommunications Providers Association (ITPA) and Canadian Cable Systems Alliance Inc. (CCSA) (collectively, the “Carriers”); AND IN THE MATTER OF Procedural Order No. 4 of the OEB issued October 26, 2015 setting dates for, inter alia, evidence of the Carriers. APPENDICES to the Evidence of Michael Piaskoski Rogers Communications Partnership November 20, 2015 EB-2015-0141 APPENDIX A to the Evidence of Michael Piaskoski Rogers Communications Partnership November 20, 2015 Michael E. Piaskoski SUMMARY OF QUALIFICATIONS Eight years in Rogers Regulatory proceeded by 12 years as a telecom lawyer specializing in regulatory, competition and commercial matters. Bright, professional and ambitious performer who continually exceeds expectations. Expertise in drafting cogent, concise and easy-to-understand regulatory and legal filings and litigation materials. -

Initial Planning Document NPA 604 Numbering Relief

Initial Planning Document NPA 604 Numbering Relief 250 604 CNA Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC Canada) July 27, 1999 As Presented on 24 September 1999 INITIAL PLANNING DOCUMENT NPA 604 NUMBERING RELIEF JULY 27, 1999 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................... 1 2. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 1 3. CENTRAL OFFICE CODE EXHAUST .................................................................................................... 2 4. CODE RELIEF METHODS...................................................................................................................... 3 4.1. Geographic Split.............................................................................................................................. 3 4.1.1. Definition ...................................................................................................................................... 3 4.1.2. General Attributes ........................................................................................................................ 4 4.2. Distributed Overlay .......................................................................................................................... 4 4.2.1. Definition ..................................................................................................................................... -

PART a Definitions and General Terms 5 ITEM 100

iTeraTEL Communications CRTC 15190 ACCESS SERVICES TARIFF Original Title Page ACCESS SERVICES TARIFF This Tariff sets out the rates, terms and conditions applicable to the interconnection arrangements provisioned to providers of telecommunications services and facilities. Issue Date: December 2,2019 Effective Date: January 15, 2015 Tariff Notice 1 iTeraTEL Communications Inc. CRTC 15190 ACCESS SERVICES TARIFF Original Page 1 Explanation of Symbols The following symbols are used in this Tariff and have meanings as shown: A Increase in rate or charge C Change in wording D Discontinued rate or regulation F Reformatting of existing material with no change to rate or charge M Matter moved from its previous location N New wording, rate or charge R Reduction in rate or charge S Reissued matter Abbreviations of Companies Names The following companies names are used in this Tariff and have meanings as shown: Aliant Aliant Telecom Inc. Bell Bell Canada Bell Aliant Bell Aliant Regional Communications, Limited Partnership IslandTel Island Telecom Inc. MTS MTS Allstream Inc. MTT Maritime Tel & Tel Limited NBTel NBTel NewTel NewTel Communications NorthernTel NorthernTel, Limited Partnership SaskTel SaskTel TBayTel TBayTel TCBC TELUS Communications Company, operating in British Columbia TCC TELUS Communications Company TCI TELUS Communications Company, operating in Alberta TCQ TELUS Communications Company, operating in Quebec Télébec Télébec, société en commandite Issue Date: December 2,2019 Effective Date: January 15, 2015 Tariff Notice 1 iTeraTEL Communications Inc. CRTC 15190 ACCESS SERVICES TARIFF Original Page 2 Check Page Issue Date: December 2, 2019 Effective Date: January 15, 2020 Tariff Notice 1 iTeraTEL Communications Inc. CRTC 15190 ACCESS SERVICES TARIFF Original Page 3 Table of Contents Page Explanation of Symbols 1 Abbreviations of Companies Names 1 Check Page 2 Table of Contents 3 PART A Definitions and General Terms 5 ITEM 100. -

49807 Bell AIF Eng Clean

BELL CANADA ANNUAL INFORMATION FORM FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2001 APRIL 15, 2002 2001 T ABLE OF CONTENTS Annual Information Form for the year ended December 31, 2001 April 15, 2002 Documents Incorporated by Reference . .1 Documents incorporated by reference Part of Annual Information Form in Trade-marks . .1 Document which incorporated by reference Item 1 • Corporate Structure of Bell Canada . .2 Portions of the 2001 Bell Canada Financial Information Item 5 Item 2 • General Development of Bell Canada . .2 Item 3 • Business of Bell Canada . .3 General . .3 Principal Service Area . .5 Subsidiaries and Associated Companies . .5 Regulation . .8 Competition . .12 Capital Expenditures . .15 Environment . .15 Employee Relations . .16 Legal Proceedings . .16 Trade-marks Certain Contracts . .17 Owner Trade-mark Forward-Looking Statements . .18 Bell Canada Rings & Head Design Risk Factors . .18 (Bell Canada corporate logo) Bell Item 4 • Selected Financial Information (Consolidated) . .20 Bell World Item 5 • Management’s Discussion and Analysis . .21 Espace Bell Sympatico Item 6 • Market for the Securities of Bell Canada . .21 Bell ActiMedia Inc. Yellow Pages Item 7 • Directors and Officers of Bell Canada . .21 Bell Mobility Inc. / Bell Mobilité inc. Mobile Browser Item 8 • Additional Information . .23 Manitoba Telecom Services Inc. First Rate Schedule – Directors’ and Officers’ Remuneration . .24 Stentor Resource Centre Inc. / Datapac Centre de ressources Stentor Inc. Megalink SmartTouch AT&T Corp. AT&T MCI Communications Corporation Hyperstream OnStar Corporation Onstar NOTES: (1) Unless the context indicates otherwise, “Bell Canada” refers to Bell Canada and its subsidiaries Yahoo! Inc. Yahoo! and associated companies. (2) All dollar figures are in Canadian dollars, unless otherwise indicated. -

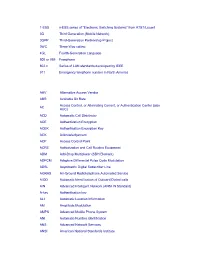

From AT&T/Lucent 3G Third Generation (Mobile Network) 3GPP

1-ESS x-ESS series of "Electronic Switching Systems" from AT&T/Lucent 3G Third Generation (Mobile Network) 3GPP Third-Generation Partnership Project 3WC Three Way calling 4GL Fourth-Generation Language 800 or 888 Freephone 802.x Series of LAN standards developed by IEEE 911 Emergency telephone number in North America AAV Alternative Access Vendor ABR Available Bit Rate Access Control, or Alternating Current, or Authentication Center (also AC AUC) ACD Automatic Call Distributor ACE Authentication Encryption ACEK Authentication Encryption Key ACK Acknowledgement ACP Access Control Point ACRE Authorization and Call Routing Equipment ADM Add-Drop Multiplexer (SDH Element) ADPCM Adaptive Differential Pulse Code Modulation ADSL Asymmetric Digital Subscriber Line AGRAS Air-Ground Radiotelephone Automated Service AIOD Automatic Identification of Outward Dialed calls AIN Advanced Intelligent Network (ANSI IN Standard) A-key Authentication key ALI Automatic Location Information AM Amplitude Modulation AMPS Advanced Mobile Phone System ANI Automatic Number Identification ANS Advanced Network Services ANSI American National Standards Institute ANSI-41 ANSI standard for mobile management (ANSI/TIA/EIA-41) ANT ADSL Network Terminator AOA Angle of Arrival AOL America On Line (ISP) API Application Programming Interface APPC Advanced Program-to Program Communications (IBM SNA) APPN Advanced Peer-to-Peer Network (IBM SNA) ARCnet Attached Resource Computer Network (Datapoint) ARDIS Advanced Radio Data Information Service ARP Address Resolution Protocol ARPA -

2020 Annual Report Dear Stockholders

2020 ANNUAL REPORT DEAR STOCKHOLDERS, 2020 was a year like no other for Consolidated Communications. Searchlight’s investment enabled us to completely refinance our debt and We entered the year with strong momentum and a clear set of strategic extend our maturity profile by seven years. Importantly, this investment goals to guide our path and focus for the year: and partnership with an experienced strategic investor in our sector is • stabilize revenue and EBITDA while growing free cash flow enabling us to accelerate our fiber expansion plans immediately. • leverage our network across the regional territories we serve while • We are in a strong position to accelerate our fiber investments with continuing to invest in the expansion of our fiber network; and a fully funded build, supporting our growth initiatives across three customer groups; carrier, commercial and consumer. We have • continue to execute on our disciplined capital allocation plan, including a embarked on a five-year investment initiative to upgrade 1.6 million strategic refinancing, to position the Company for investment in the future. passings and enable multi-gigabit, symmetrical speeds over fiber services. And then the COVID-19 pandemic arrived, testing us in previously We have a proven track record of growing broadband, and we are now unimaginable ways. But your Company and its employees responded positioned to expedite our fiber expansion plans, boost customer speeds with incredible energy, engagement and support for one another. We and expand gigabit fiber services to 70 percent of our addressable market. focused immediately and intensely to ensure the safety of our employees As part of our fiber expansion plans, we intend to transform the customer and customers while at the same time ensuring business continuity and experience by making it easy for customers to do business with us. -

The International Communications Market 2016

The International Communications Market 2016 4 4 TV and audio-visual 117 Contents 4.1 TV and audio-visual: overview and key market developments 119 Overview 119 Subscriptions to video-on-demand services continue to grow 121 4.2 The TV and audio-visual industry 125 Revenues 125 The licence fee and public funding 130 4.3 The TV and audio-visual consumer 132 Digital TV take-up 132 IPTV services and take-up 135 Value-added services 135 Broadcast television viewing 138 Legacy terrestrial channels viewing 139 Domestic publicly-owned channels viewing 140 118 4.1 TV and audio-visual: overview and key market developments Overview Subscription revenues continued to make up over half of total TV revenue Global TV revenues from broadcast advertising, channel subscription and public funding including licence fees reached £263bn in 2015. Subscription revenues continue to make up over half of total revenue, at £137bn. TV revenue per capita in the UK was £221 in 2015, the third highest of our comparator countries after Germany (£289) and the US (£351). South Korea had the highest take-up of pay TV at 99%, compared to the UK which had one of the lowest of our comparator countries at 62%. Just over half of UK television homes received an HD service in 2015 (51%), putting the UK in tenth position among our 18 comparator countries. Declines in viewing to broadcast TV occurred across many countries The UK experienced a year-on-year decline in viewing to broadcast TV (-1.9%), with people watching an average of 3 hours 36 minutes of TV each day. -

Advanced Info Services (AIS), 155 Advanced Wireless Research Initiative (AWRI), 35 Africa, 161-162 AIR 6468, 23 Alaskan Telco GC

Index Advanced Info Services (AIS), 155 Belgium Competition Authority Advanced Wireless Research Initiative (BCA), 73 (AWRI), 35 Bharti Airtel, 144, 162 Africa, 161–162 Bite,´ 88 AIR 6468, 23 Bouygues, 79 Alaskan telco GCI, 134 Brazil, 125 Altice USA, 132 Broadband Radio Services (BRS), America´ Movil,´ 125, 129 137–138 Android, 184 BT Plus, 105 Antel, 139 BT/EE, 185 Apple, 186–190 Bulgaria, 74 Asia Pacific Telecom (APT), 154 Asia-Pacific Telecommunity (APT), 6, C-band, 26 25–26 Cableco/MVNO CJ Hello, 153 AT&T, 129, 131 Canada, 125–127 Auction Carrier aggregation (CA), 5, 22 coverage obligation, 10 CAT Telecom, 155 plans, 137–139 Cellular IoT (CIoT), 31 reserve prices, 9 Centimetre wave (cmWave), 34–35 Auction methods, 8–9 Centuria, 88 combinatorial clock, 8 Ceragon Networks, 93 simultaneous multi-round Channel Islands Competition and ascending, 8 Regulatory Authorities Augmented reality, 195 (CICRA), 83, 88 Australia, 139–140 Chief Technology Officer (CTO), 185 Austria, 71–73 Chile, 127–128 Autonomous transport, 195 Chile, private networks, 127–128 Average revenue per user (ARPU), China, 141–142 165–166, 197 China Broadcasting Network (CBN), Axtel, 129 141 China Mobile, 141 Backhaul, 24–25 China Telecom, 141 Bahrain, 156 China Unicom, 39, 141–142 Batelco, 156 Chipsets, 186–190 Beamforming, 24, 29 Chunghwa Telecom, 154 Beauty contest, 8 Citizens Broadband Radio Service Belgacom, 73 (CBRS), 130–131 Belgium, 73–74 CK Hutchison, 145 210 Index Cloud computing, 24 Eir Group, 85 Co-operative MIMO. See Coordinated Electromagnetic fields (EMFs), 38–39 -

Internet Hall of Fame Announces 2013 Inductees

Internet Hall of Fame Announces 2013 Inductees Influential engineers, activists, and entrepreneurs changed history through their vision and determination Ceremony to be held 3 August in Berlin, Germany [Washington, D.C. and Geneva, Switzerland -- 26 June 2013] The Internet Society today announced the names of the 32 individuals who have been selected for induction into the Internet Hall of Fame. Honored for their groundbreaking contributions to the global Internet, this year’s inductees comprise some of the world’s most influential engineers, activists, innovators, and entrepreneurs. The Internet Hall of Fame celebrates Internet visionaries, innovators, and leaders from around the world who believed in the design and potential of an open Internet and, through their work, helped change the way we live and work today. The 2013 Internet Hall of Fame inductees are: Pioneers Circle – Recognizing individuals who were instrumental in the early design and development of the Internet: David Clark, David Farber, Howard Frank, Kanchana Kanchanasut, J.C.R. Licklider (posthumous), Bob Metcalfe, Jun Murai, Kees Neggers, Nii Narku Quaynor, Glenn Ricart, Robert Taylor, Stephen Wolff, Werner Zorn Innovators – Recognizing individuals who made outstanding technological, commercial, or policy advances and helped to expand the Internet’s reach: Marc Andreessen, John Perry Barlow, Anne-Marie Eklund Löwinder, François Flückiger, Stephen Kent, Henning Schulzrinne, Richard Stallman, Aaron Swartz (posthumous), Jimmy Wales Global Connectors – Recognizing individuals from around the world who have made significant contributions to the global growth and use of the Internet: Karen Banks, Gihan Dias, Anriette Esterhuysen, Steven Goldstein, Teus Hagen, Ida Holz, Qiheng Hu, Haruhisa Ishida (posthumous), Barry Leiner (posthumous), George Sadowsky “This year’s inductees represent a group of people as diverse and dynamic as the Internet itself,” noted Internet Society President and CEO Lynn St. -

The Impact of Over the Top Service Providers on the Global Mobile Telecom Industry: a Quantified Analysis and Recommendations for Recovery

The impact of Over The Top service providers on the Global Mobile Telecom Industry: A quantified analysis and recommendations for recovery Ahmed Awwad Faculty of Science and Engineering, Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge Campus, East Rd, Cambridge CB1 1PT, United Kingdom. [email protected] Key words: Mobile Network Operators (MNO), Over the top (OTT), Telecom industry revenue decrease, telecom operator’s revenue growth strategies. This work is licensed under Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ABSTRACT Telecom industry is significantly evolving all over the analysis of global MNOs` revenue over the last globe than ever. Mobile users’ number is increasing decade. Additionally, the research aims to compile, remarkably. Telecom operators are investing to get evaluate, and analyse set of former proposed more users connected and to improve user strategies for MNOs to overcome the OTTs` impact. experience, however, they are facing various Methods –Referring to available open source raw challenges. Decrease of main revenue streams of data collected from GSMA and official voice calls, SMS (Short Message Service) and LDC telecommunications regulatory authorities (Long distance calls) with a significant increase in data worldwide, the research develops a statistical model traffic. In contrary, with free cost, OTT (Over the based on regression and extrapolation to analyse the top) providers such as WhatsApp and Facebook global MNOs` revenue trend. communication services rendered over networks that Findings – This study reveals a hidden revenue loss built and owned by MNOs. Recently, OTT services for global telecommunications industry represented gradually substituting the traditional MNOs` services in all MNOs all over the world.