Industry Guidance for Clinical Trial Imaging Endpoint Process Standards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Statement by the Association of Hoving Image Archivists (AXIA) To

Statement by the Association of Hoving Image Archivists (AXIA) to the National FTeservation Board, in reference to the Uational Pilm Preservation Act of 1992, submitted by Dr. Jan-Christopher Eorak , h-esident The Association of Moving Image Archivists was founded in November 1991 in New York by representatives of over eighty American and Canadian film and television archives. Previously grouped loosely together in an ad hoc organization, Pilm Archives Advisory Committee/Television Archives Advisory Committee (FAAC/TAAC), it was felt that the field had matured sufficiently to create a national organization to pursue the interests of its constituents. According to the recently drafted by-laws of the Association, AHIA is a non-profit corporation, chartered under the laws of California, to provide a means for cooperation among individuals concerned with the collection, preservation, exhibition and use of moving image materials, whether chemical or electronic. The objectives of the Association are: a.) To provide a regular means of exchanging information, ideas, and assistance in moving image preservation. b.) To take responsible positions on archival matters affecting moving images. c.) To encourage public awareness of and interest in the preservation, and use of film and video as an important educational, historical, and cultural resource. d.) To promote moving image archival activities, especially preservation, through such means as meetings, workshops, publications, and direct assistance. e. To promote professional standards and practices for moving image archival materials. f. To stimulate and facilitate research on archival matters affecting moving images. Given these objectives, the Association applauds the efforts of the National Film Preservation Board, Library of Congress, to hold public hearings on the current state of film prese~ationin 2 the United States, as a necessary step in implementing the National Film Preservation Act of 1992. -

Information Visualization Lecture 5

Information Visualization Lecture 5 IVIS15 Skylike (link to project, link to video) Mario Romero 2016/02/02 Proposal for Skylike IVIS15 Skylike proposal on Feb 13, 2015: “make night sky constellations from your network of friends.” 2016-02-02 IVIS16 L5 2 Feedback to Proposal: link to presentation PDF Diana, Andrés, Willie, Tomáš, Johanna: Your proposal is ambitious in some aspects and unclear in others. It is ambitious in its plan to compute constellations from network graphs. What is a constellation mathematically? You will need graph theory, a sophisticated data transformation. How many stars and links for a typical constellation? Why? Are there families of constellations? How do you represent the constellations within the network? What are the view transformations? How do you provide overview, zooming, filtering, details on demand? You need to focus. Who is your user? What are the tasks? Where do you get your raw data? You need refine your ideas. Using the 4K screen with the kinect may work. 2016-02-02 IVIS16 L5 3 Skylikes feedback to ”Hello World” Demo Diana, Andrés, Willie, Tomáš, Johanna: Your choice of focusing on Goodreads is wise. Your Hello World demo worked very well and it gave your classmates a concrete opportunity to provide actionable feedback. Good work. Your challenge remains the graph theory to compute reasonable constellations in the number of stars and edges and their location. For example, should you strive for planar graphs? How many nodes and edges? Where do you place the cut off? Also, you have to think about your query system and the permanence of the constellations across users, sessions, and networks of friends. -

Lab 11: the Compound Microscope

OPTI 202L - Geometrical and Instrumental Optics Lab 9-1 LAB 9: THE COMPOUND MICROSCOPE The microscope is a widely used optical instrument. In its simplest form, it consists of two lenses Fig. 9.1. An objective forms a real inverted image of an object, which is a finite distance in front of the lens. This image in turn becomes the object for the ocular, or eyepiece. The eyepiece forms the final image which is virtual, and magnified. The overall magnification is the product of the individual magnifications of the objective and the eyepiece. Figure 9.1. Images in a compound microscope. To illustrate the concept, use a 38 mm focal length lens (KPX079) as the objective, and a 50 mm focal length lens (KBX052) as the eyepiece. Set them up on the optical rail and adjust them until you see an inverted and magnified image of an illuminated object. Note the intermediate real image by inserting a piece of paper between the lenses. Q1 ● Can you demonstrate the final image by holding a piece of paper behind the eyepiece? Why or why not? The eyepiece functions as a magnifying glass, or simple magnifier. In effect, your eye looks into the eyepiece, and in turn the eyepiece looks into the optical system--be it a compound microscope, a spotting scope, telescope, or binocular. In all cases, the eyepiece doesn't view an actual object, but rather some intermediate image formed by the "front" part of the optical system. With telescopes, this intermediate image may be real or virtual. With the compound microscope, this intermediate image is real, formed by the objective lens. -

Image Compression Using Discrete Cosine Transform Method

Qusay Kanaan Kadhim, International Journal of Computer Science and Mobile Computing, Vol.5 Issue.9, September- 2016, pg. 186-192 Available Online at www.ijcsmc.com International Journal of Computer Science and Mobile Computing A Monthly Journal of Computer Science and Information Technology ISSN 2320–088X IMPACT FACTOR: 5.258 IJCSMC, Vol. 5, Issue. 9, September 2016, pg.186 – 192 Image Compression Using Discrete Cosine Transform Method Qusay Kanaan Kadhim Al-Yarmook University College / Computer Science Department, Iraq [email protected] ABSTRACT: The processing of digital images took a wide importance in the knowledge field in the last decades ago due to the rapid development in the communication techniques and the need to find and develop methods assist in enhancing and exploiting the image information. The field of digital images compression becomes an important field of digital images processing fields due to the need to exploit the available storage space as much as possible and reduce the time required to transmit the image. Baseline JPEG Standard technique is used in compression of images with 8-bit color depth. Basically, this scheme consists of seven operations which are the sampling, the partitioning, the transform, the quantization, the entropy coding and Huffman coding. First, the sampling process is used to reduce the size of the image and the number bits required to represent it. Next, the partitioning process is applied to the image to get (8×8) image block. Then, the discrete cosine transform is used to transform the image block data from spatial domain to frequency domain to make the data easy to process. -

Identifying Robust Plans Through Plan Diagram Reduction

Identifying Robust Plans through Plan Diagram Reduction ∗ Harish D. Pooja N. Darera Jayant R. Haritsa Database Systems Lab, SERC/CSA Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore 560012, INDIA ABSTRACT tary and conceptually different approach, which we consider in this Estimates of predicate selectivities by database query optimizers paper, is to identify robust plans that are relatively less sensitive to often differ significantly from those actually encountered during such selectivity errors. In a nutshell, to “aim for resistance, rather query execution, leading to poor plan choices and inflated response than cure”, by identifying plans that provide comparatively good times. In this paper, we investigate mitigating this problem by performance over large regions of the selectivity space. Such plan replacing selectivity error-sensitive plan choices with alternative choices are especially important for industrial workloads where plans that provide robust performance. Our approach is based on global stability is as much a concern as local optimality [18]. the recent observation that even the complex and dense “plan di- Over the last decade, a variety of strategies have been proposed agrams” associated with industrial-strength optimizers can be ef- to identify robust plans, including the Least Expected Cost [6, 8], ficiently reduced to “anorexic” equivalents featuring only a few Robust Cardinality Estimation [2] and Rio [3, 4] approaches. These plans, without materially impacting query processing quality. techniques provide novel and elegant formulations (summarized in Extensive experimentation with a rich set of TPC-H and TPC- Section 6), but have to contend with the following issues: DS-based query templates in a variety of database environments Firstly, they are intrusive requiring, to varying degrees, modifi- indicate that plan diagram reduction typically retains plans that are cations to the optimizer engine. -

Ground-Based Photographic Monitoring

United States Department of Agriculture Ground-Based Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station Photographic General Technical Report PNW-GTR-503 Monitoring May 2001 Frederick C. Hall Author Frederick C. Hall is senior plant ecologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Region, Natural Resources, P.O. Box 3623, Portland, Oregon 97208-3623. Paper prepared in cooperation with the Pacific Northwest Region. Abstract Hall, Frederick C. 2001 Ground-based photographic monitoring. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-503. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 340 p. Land management professionals (foresters, wildlife biologists, range managers, and land managers such as ranchers and forest land owners) often have need to evaluate their management activities. Photographic monitoring is a fast, simple, and effective way to determine if changes made to an area have been successful. Ground-based photo monitoring means using photographs taken at a specific site to monitor conditions or change. It may be divided into two systems: (1) comparison photos, whereby a photograph is used to compare a known condition with field conditions to estimate some parameter of the field condition; and (2) repeat photo- graphs, whereby several pictures are taken of the same tract of ground over time to detect change. Comparison systems deal with fuel loading, herbage utilization, and public reaction to scenery. Repeat photography is discussed in relation to land- scape, remote, and site-specific systems. Critical attributes of repeat photography are (1) maps to find the sampling location and of the photo monitoring layout; (2) documentation of the monitoring system to include purpose, camera and film, w e a t h e r, season, sampling technique, and equipment; and (3) precise replication of photographs. -

The Microscope Parts And

The Microscope Parts and Use Name:_______________________ Period:______ Historians credit the invention of the compound microscope to the Dutch spectacle maker, Zacharias Janssen, around the year 1590. The compound microscope uses lenses and light to enlarge the image and is also called an optical or light microscope (vs./ an electron microscope). The simplest optical microscope is the magnifying glass and is good to about ten times (10X) magnification. The compound microscope has two systems of lenses for greater magnification, 1) the ocular, or eyepiece lens that one looks into and 2) the objective lens, or the lens closest to the object. Before purchasing or using a microscope, it is important to know the functions of each part. Eyepiece Lens: the lens at the top that you look through. They are usually 10X or 15X power. Tube: Connects the eyepiece to the objective lenses Arm: Supports the tube and connects it to the base. It is used along with the base to carry the microscope Base: The bottom of the microscope, used for support Illuminator: A steady light source (110 volts) used in place of a mirror. Stage: The flat platform where you place your slides. Stage clips hold the slides in place. Revolving Nosepiece or Turret: This is the part that holds two or more objective lenses and can be rotated to easily change power. Objective Lenses: Usually you will find 3 or 4 objective lenses on a microscope. They almost always consist of 4X, 10X, 40X and 100X powers. When coupled with a 10X (most common) eyepiece lens, we get total magnifications of 40X (4X times 10X), 100X , 400X and 1000X. -

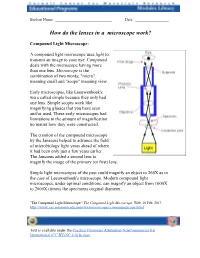

How Do the Lenses in a Microscope Work?

Student Name: _____________________________ Date: _________________ How do the lenses in a microscope work? Compound Light Microscope: A compound light microscope uses light to transmit an image to your eye. Compound deals with the microscope having more than one lens. Microscope is the combination of two words; "micro" meaning small and "scope" meaning view. Early microscopes, like Leeuwenhoek's, were called simple because they only had one lens. Simple scopes work like magnifying glasses that you have seen and/or used. These early microscopes had limitations to the amount of magnification no matter how they were constructed. The creation of the compound microscope by the Janssens helped to advance the field of microbiology light years ahead of where it had been only just a few years earlier. The Janssens added a second lens to magnify the image of the primary (or first) lens. Simple light microscopes of the past could magnify an object to 266X as in the case of Leeuwenhoek's microscope. Modern compound light microscopes, under optimal conditions, can magnify an object from 1000X to 2000X (times) the specimens original diameter. "The Compound Light Microscope." The Compound Light Microscope. Web. 16 Feb. 2017. http://www.cas.miamioh.edu/mbi-ws/microscopes/compoundscope.html Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) license. - 1 – Student Name: _____________________________ Date: _________________ Now we will describe how a microscope works in somewhat more detail. The first lens of a microscope is the one closest to the object being examined and, for this reason, is called the objective. -

Current Strategies for Reducing Recidivism

CURRENT STRATEGIES FOR REDUCING RECIDIVISM LISE MCKEAN, PH.D. CHARLES RANSFORD CENTER FOR IMPACT RESEARCH AUGUST 2004 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS PROJECT FUNDER Chicago Community Organizing Capacity Building Initiative PROJECT PARTNERS Developing Justice Coalition Coalition Members ACORN Ambassadors for Christ Church Brighton Park Neighborhood Council Chicago Coalition for the Homeless Community Renewal Society Developing Communities Project Foster Park Neighborhood Council Garfield Area Partnership Global Outreach Ministries Inner-City Muslim Action Network Northwest Neighborhood Federation Organization of the North East Protestants for the Common Good SERV-US Southwest Organizing Project Target Area Development Corp. West Side Health Authority Center for Impact Research Project Staff Lise McKean, Ph.D., Project Director Charles Ransford 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY……………………………………………… 4 INTRODUCTION …………………………...……………………….. 8 STUDY DESIGN……………………………………………………… 9 DEFINING RECIDIVISM……………………………………………… 11 FINDINGS ON PROGRAMS ………………………………………….. 15 Treatment Programs………………………………………….. 15 Educational Programs……………………………………....... 18 Employment Programs………………………………………. 19 Other Types of Programs……………………………….......... 21 RECOMMENDATIONS …………..…………………………………… 24 APPENDIX…..………………………………………………………. 27 3 CURRENT STRATEGIES FOR REDUCING RECIDIVISM Lise McKean, Ph.D., and Charles Ransford Center for Impact Research August 2004 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Recidivism is the relapse into criminal activity and is generally measured by a former prisoner’s return to prison for a new offense. Rates of recidivism reflect the degree to which released inmates have been rehabilitated and the role correctional programs play in reintegrating prisoners into society. The rate of recidivism in the U.S. is estimated to be about two-thirds, which means that two-thirds of released inmates will be re-incarcerated within three years. High rates of recidivism result in tremendous costs both in terms of public safety and in tax dollars spent to arrest, prosecute, and incarcerate re-offenders. -

The Language of Spatial ANALYSIS CONTENTS

The Language of spatial ANALYSIS CONTENTS Foreword How to use this book Chapter 1 An introduction to spatial analysis Chapter 2 The vocabulary of spatial analysis Understanding where Measuring size, shape, and distribution Determining how places are related Finding the best locations and paths Detecting and quantifying patterns Making predictions Chapter 3 The seven steps to successful spatial analysis Chapter 4 The benefits of spatial analysis Case study Bringing it all together to solve the problem Reference A quick guide to spatial analysis Additional resources FOREWORD Watching the GIS industry grow for more than 25 years, I have seen innovation in the problems we solve, the people we can reach through technology, the stories we tell, and the decisions that help make our organizations and the world more successful. However, what has not changed is our longstanding goal to better understand our world through spatial analysis. Traveling the world I have met people from many diverse cultures who work in a wide range of industries. However, as I listen to their mission and challenges, there is a common pattern: we all speak the same language—it is the language of spatial analysis. This language consists of a core set of questions that we ask, a taxonomy that organizes and expands our understanding, and the fundamental steps to spatial analysis that embody how we solve spatial problems. I encourage each of you to learn and communicate to the world the power of spatial analysis. Learn the definition, learn the vocabulary and the process, and most important, be able to speak this language to the world. -

A Curriculum Guide

FOCUS ON PHOTOGRAPHY: A CURRICULUM GUIDE This page is an excerpt from Focus on Photography: A Curriculum Guide Written by Cynthia Way for the International Center of Photography © 2006 International Center of Photography All rights reserved. Published by the International Center of Photography, New York. Printed in the United States of America. Please credit the International Center of Photography on all reproductions. This project has been made possible with generous support from Andrew and Marina Lewin, the GE Fund, and public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs Cultural Challenge Program. FOCUS ON PHOTOGRAPHY: A CURRICULUM GUIDE PART IV Resources FOCUS ON PHOTOGRAPHY: A CURRICULUM GUIDE This section is an excerpt from Focus on Photography: A Curriculum Guide Written by Cynthia Way for the International Center of Photography © 2006 International Center of Photography All rights reserved. Published by the International Center of Photography, New York. Printed in the United States of America. Please credit the International Center of Photography on all reproductions. This project has been made possible with generous support from Andrew and Marina Lewin, the GE Fund, and public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs Cultural Challenge Program. FOCUS ON PHOTOGRAPHY: A CURRICULUM GUIDE Focus Lesson Plans Fand Actvities INDEX TO FOCUS LINKS Focus Links Lesson Plans Focus Link 1 LESSON 1: Introductory Polaroid Exercises Focus Link 2 LESSON 2: Camera as a Tool Focus Link 3 LESSON 3: Photographic Field -

Recommended Drawing Numbering, Scales and Dimensioning 1 / 3

Recommended Drawing Numbering, Scales and Dimensioning 1 / 3 Architectural Drawings: General: G101 Cover Sheet G102 General Information G201 Live Safety Plan Civil: C100 Site Topo Plan C200 Demolition Plan C300 Site Staking/Signing/Striping/Erosion Control Plan C400 Grading & Drainage Plan C500 Utility Plan Landscape: I‐1 Irrigation Plan I‐2 Irrigation Details L‐1 Landscape Plan L‐2 Landscape Details Architectural: AC01 Overall Architectural Site Plan AC02 Enlarged Architectural Site Plan AC03 Site Plan Details A001 Finish Schedule & Legend A002 Opening Schedule, Elevations A101 Floor Plan A102 Dimension Plan A103 Lower Roof Plan A104 Upper Roof Plan A105 Canopy Plan and Details A111 Enlarged Floor Plans A201 Exterior Elevations A201 Exterior Elevations A301 Building Sections A302 Building Sections A311 Wall Sections A312 Details – Curved Roof A313 Details – Curved Roof A316 Wall Partition Types A321 Plan Details A331 Section Details A332 Typical Details and Profiles A341 Roof Details A351 Interior Column Details A401 Interior Elevations A402 Interior Elevations A501 Reflected Ceiling Plan A601 Equipment Plan Recommended Drawing Numbering, Scales and Dimensioning 2 / 3 The recommendation scales* for key architectural drawings are as follows: Site plan – engineering scale 1:20 or similar, depend upon size of site Arch Floor Plan – 1/8” Arch Ceiling Plan – 1/8” Arch Roof Plan – 1/8” or 1/16” – (try to show roof as one drawing view) Interiors Floor Finish Plan – 1/8” Interiors Furniture Plan – 1/8” Enlarged Arch Floor Plans – ¼” or larger as needed (typically the toilet rooms) Arch Exterior Elevations – 1/8” Arch Building Section – ¼” or ½” if needed for a specialty area (ie lobby) Arch typical wall sections – ¾” Wall types (wall sections or plan views) – 1 ½” Details ‐ Plan and Section – 1 ½” or 3” Interior Elevations – ¼” or 3/8” as needed *Note: set up each drawing on a 42” x 30” page.