STARS Contact

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020)

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020) Vertrieb Interpret Titel Info Format Inhalt Label Genre Artikelnummer UPC/EAN AT+CH (ja/nein/über wen?) Exclusive Record Store Day version pressed on 7" picture disc! Top song on Billboard's 375Media Ace Of Base The Sign 7" 1 !K7 Pop SI 174427 730003726071 D 1994 Year End Chart. [ENG]Pink heavyweight 180 gram audiophile double vinyl LP. Not previously released on vinyl. 'Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo' was first released on CD only in 2007 by Ace Fu SPACE AGE 375MEDIA ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE NAM MYO HO REN GE KYO (RSD PINK VINYL) LP 2 PSYDEL 139791 5023693106519 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Records and now re-mastered by John Rivers at Woodbine Street Studio especially for RECORDINGS vinyl Out of print on vinyl since 1984, FIRST official vinyl reissue since 1984 -Chet Baker (1929 - 1988) was an American jazz trumpeter, actor and vocalist that needs little introduction. This reissue was remastered by Peter Brussee (Herman Brood) and is featuring the original album cover shot by Hans Harzheim (Pharoah Sanders, Coltrane & TIDAL WAVES 375MEDIA BAKER, CHET MR. B LP 1 JAZZ 139267 0752505992549 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Sun Ra). Also included are the original liner notes from jazz writer Wim Van Eyle and MUSIC two bonus tracks that were not on the original vinyl release. This reissue comes as a deluxe 180g vinyl edition with obi strip_released exclusively for Record Store Day (UK & Europe) 2020. * Record Store Day 2020 Exclusive Release.* Features new artwork* LP pressed on pink vinyl & housed in a gatefold jacket Limited to 500 copies//Last Tango in Paris" is a 1972 film directed by Bernardo Bertolucci, saxplayer Gato Barbieri' did realize the soundtrack. -

John Lennon from ‘Imagine’ to Martyrdom Paul Mccartney Wings – Band on the Run George Harrison All Things Must Pass Ringo Starr the Boogaloo Beatle

THE YEARS 1970 -19 8 0 John Lennon From ‘Imagine’ to martyrdom Paul McCartney Wings – band on the run George Harrison All things must pass Ringo Starr The boogaloo Beatle The genuine article VOLUME 2 ISSUE 3 UK £5.99 Packed with classic interviews, reviews and photos from the archives of NME and Melody Maker www.jackdaniels.com ©2005 Jack Daniel’s. All Rights Reserved. JACK DANIEL’S and OLD NO. 7 are registered trademarks. A fine sippin’ whiskey is best enjoyed responsibly. by Billy Preston t’s hard to believe it’s been over sent word for me to come by, we got to – all I remember was we had a groove going and 40 years since I fi rst met The jamming and one thing led to another and someone said “take a solo”, then when the album Beatles in Hamburg in 1962. I ended up recording in the studio with came out my name was there on the song. Plenty I arrived to do a two-week them. The press called me the Fifth Beatle of other musicians worked with them at that time, residency at the Star Club with but I was just really happy to be there. people like Eric Clapton, but they chose to give me Little Richard. He was a hero of theirs Things were hard for them then, Brian a credit for which I’m very grateful. so they were in awe and I think they had died and there was a lot of politics I ended up signing to Apple and making were impressed with me too because and money hassles with Apple, but we a couple of albums with them and in turn had I was only 16 and holding down a job got on personality-wise and they grew to the opportunity to work on their solo albums. -

My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R. Fisher Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS By David R. Fisher A thesis submitted to the College of Music In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of David Fisher on March 29, 2006. ______________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis ______________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member ______________________________ Evan Jones Outside Committee M ember The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables......................................................................................................................iv Abstract................................................................................................................................v 1. THE ORIGINS OF THE SHOEGAZER.........................................................................1 2. A BIOGRAPHICAL ACCOUNT OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE.………..………17 3. AN ANALYSIS OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS...............................28 4. LOVELESS AND ITS LEGACY...................................................................................50 BIBLIOGRAPHY..............................................................................................................63 -

Indian Horse

Contents 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 41 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 47 | 48 | 49 | 50 | 51 | 52 | 53 | 54 | 55 | 56 Acknowledgements | Copyright For my wife, Debra Powell, for allowing me to bask in her light and become more. I come into the peace of wild things who do not tax their lives with forethought of grief. I come into the presence of still water. And I feel above me the day-blind stars waiting with their light. For a time I rest in the grace of the world, and am free. WENDELL BERRY, “The Peace of Wild Things” 1 My name is Saul Indian Horse. I am the son of Mary Mandamin and John Indian Horse. My grandfather was called Solomon so my name is the diminutive of his. My people are from the Fish Clan of the northern Ojibway, the Anishinabeg, we call ourselves. We made our home in the territories along the Winnipeg River, where the river opens wide before crossing into Manitoba after it leaves Lake of the Woods and the rugged spine of northern Ontario. They say that our cheekbones are cut from those granite ridges that rise above our homeland. They say that the deep brown of our eyes seeped out of the fecund earth that surrounds the lakes and marshes. The Old Ones say that our long straight hair comes from the waving grasses that thatch the edges of bays. -

INTERVIEWS from the 90'S

INTERVIEWS FROM THE 90’s 1 INTERVIEWS FROM THE 90’S p4. THE SONG TALK INTERVIEW, 1991 p27. THE AGE, APRIL 3, 1992 (MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA) p30. TIMES THEY ARE A CHANGIN'.... DYLAN SPEAKS, APRIL 7, 1994 p33. NEWSWEEK, MARCH 20, 1995 p36. EDNA GUNDERSEN INTERVIEW, USA TODAY, MAY 5, 1995 p40. SUN-SENTINEL TODAY, FORT LAUDERDALE, SEPT. 29, 1995 p45. NEW YORK TIMES, SEPT. 27, 1997 p52. USA TODAY, SEPT. 28, 1997 p57. DER SPIEGEL, OCT. 16, 1997 p66. GUITAR WORLD MAGAZINE, MARCH 1999 Source: http://www.interferenza.com/bcs/interv.htm 2 3 THE SONG TALK INTERVIEW, 1991 Bob Dylan: The Song Talk Interview. By: Paul Zollo Date: 1991 Transcribed from GBS #3 booklet "I've made shoes for everyone, even you, while I still go barefoot" from "I and I" By Bob Dylan Songwriting? What do I know about songwriting? Bob Dylan asked, and then broke into laughter. He was wearing blue jeans and a white tank-top T-shirt, and drinking coffee out of a glass. "It tastes better out of a glass," he said grinning. His blonde acoustic guitar was leaning on a couch near where we sat. Bob Dylan's guitar . His influence is so vast that everything that surrounds takes on enlarged significance: Bob Dylan's moccasins. Bob Dylan's coat . "And the ghost of 'lectricity howls in the bones of her face Where these visions of Johanna have now taken my place. The harmonicas play the skeleton keys and the rain And these visions of Johanna are now all that remain" from "Visions of Johanna" Pete Seeger said, "All songwriters are links in a chain," yet there are few artists in this evolutionary arc whose influence is as profound as that of Bob Dylan. -

Marxman Mary Jane Girls Mary Mary Carolyne Mas

Key - $ = US Number One (1959-date), ✮ UK Million Seller, ➜ Still in Top 75 at this time. A line in red 12 Dec 98 Take Me There (Blackstreet & Mya featuring Mase & Blinky Blink) 7 9 indicates a Number 1, a line in blue indicate a Top 10 hit. 10 Jul 99 Get Ready 32 4 20 Nov 04 Welcome Back/Breathe Stretch Shake 29 2 MARXMAN Total Hits : 8 Total Weeks : 45 Anglo-Irish male rap/vocal/DJ group - Stephen Brown, Hollis Byrne, Oisin Lunny and DJ K One 06 Mar 93 All About Eve 28 4 MASH American male session vocal group - John Bahler, Tom Bahler, Ian Freebairn-Smith and Ron Hicklin 01 May 93 Ship Ahoy 64 1 10 May 80 Theme From M*A*S*H (Suicide Is Painless) 1 12 Total Hits : 2 Total Weeks : 5 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 12 MARY JANE GIRLS American female vocal group, protégées of Rick James, made up of Cheryl Ann Bailey, Candice Ghant, MASH! Joanne McDuffie, Yvette Marine & Kimberley Wuletich although McDuffie was the only singer who Anglo-American male/female vocal group appeared on the records 21 May 94 U Don't Have To Say U Love Me 37 2 21 May 83 Candy Man 60 4 04 Feb 95 Let's Spend The Night Together 66 1 25 Jun 83 All Night Long 13 9 Total Hits : 2 Total Weeks : 3 08 Oct 83 Boys 74 1 18 Feb 95 All Night Long (Remix) 51 1 MASON Dutch male DJ/producer Iason Chronis, born 17/1/80 Total Hits : 4 Total Weeks : 15 27 Jan 07 Perfect (Exceeder) (Mason vs Princess Superstar) 3 16 MARY MARY Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 16 American female vocal duo - sisters Erica (born 29/4/72) & Trecina (born 1/5/74) Atkins-Campbell 10 Jun 00 Shackles (Praise You) -

WOLF 359 "BRAVE NEW WORLD" by Gabriel Urbina Story By: Sarah Shachat & Gabriel Urbina

WOLF 359 "BRAVE NEW WORLD" by Gabriel Urbina Story by: Sarah Shachat & Gabriel Urbina Writer's Note: This episode takes place starting on Day 1220 of the Hephaestus Mission. FADE IN: On HERA. Speaking directly to us. HERA So here's a story. Once upon a time, there lived a broken little girl. She was born with clouded eyes, and a weak heart, not destined to beat through an entire lifetime. But instead of being wretched or afraid, the little girl decided to be clever. She got very, very good at fixing things. First she fixed toys, and clocks, and old machines that no one thought would ever run again. Then, she fixed bigger things. She fixed the cold and drafty orphanage where she grew up; when she went to school, she fixed equations to make them more useful; everything around her, she made better... and sharper... and stronger. She had no friends, of course, except for the ones she made. The little girl had a talent for making dolls - beautiful, wonderful mechanical dolls - and she thought they were better friends than anyone in the world. They could be whatever she wanted them to be - and as real as she wanted them to be - and they never left her behind... and they never talked back... and they were never afraid of her. Except when she wanted them to be. But if there was one thing the girl never felt like she could fix, it was herself. Until... one day a strange thing happened. The broken girl met an old man - older than anyone she had ever met, but still tricky and clever, almost as clever as the girl. -

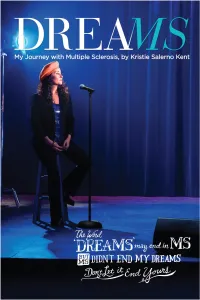

Dreams-041015 1.Pdf

DREAMS My Journey with Multiple Sclerosis By Kristie Salerno Kent DREAMS: MY JOURNEY WITH MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS. Copyright © 2013 by Acorda Therapeutics®, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Author’s Note I always dreamed of a career in the entertainment industry until a multiple sclerosis (MS) diagnosis changed my life. Rather than give up on my dream, following my diagnosis I decided to fight back and follow my passion. Songwriting and performance helped me find the strength to face my challenges and help others understand the impact of MS. “Dreams: My Journey with Multiple Sclerosis,” is an intimate and honest story of how, as people living with MS, we can continue to pursue our passion and use it to overcome denial and find the courage to take action to fight MS. It is also a story of how a serious health challenge does not mean you should let go of your plans for the future. The word 'dreams' may end in ‘MS,’ but MS doesn’t have to end your dreams. It has taken an extraordinary team effort to share my story with you. This book is dedicated to my greatest blessings - my children, Kingston and Giabella. You have filled mommy's heart with so much love, pride and joy and have made my ultimate dream come true! To my husband Michael - thank you for being my umbrella during the rainy days until the sun came out again and we could bask in its glow together. Each end of our rainbow has two pots of gold… our precious son and our beautiful daughter! To my heavenly Father, thank you for the gifts you have blessed me with. -

Diverse on Screen Talent Directory

BBC Diverse Presenters The BBC is committed to finding and growing diverse onscreen talent across all channels and platforms. We realise that in order to continue making the BBC feel truly diverse, and improve on where we are at the moment, we need to let you know who’s out there. In this document you will find biographies for just some of the hugely talented people the BBC has already been working with and others who have made their mark elsewhere. It’s the responsibility of every person involved in BBC programme making to ask themselves whether what, and who, they are putting on screen reflects the world around them or just one section of society. If you are in production or development and would like other ideas for diverse presenters across all genres please feel free to get in touch with Mary Fitzpatrick Editorial Executive, Diversity via email: [email protected] Diverse On Screen Talent Directory Presenter Biographies Biographies Ace and Invisible Presenters, 1Xtra Category: 1Xtra Agent: Insanity Artists Agency Limited T: 020 7927 6222 W: www.insanityartists.co.uk 1Xtra's lunchtime DJs Ace and Invisible are on a high - the two 22-year-olds scooped the gold award for Daily Music Show of the Year at the 2004 Sony Radio Academy Awards. It's a just reward for Ace and Invisible, two young south Londoners with high hopes who met whilst studying media at the Brits Performing Arts School in 1996. The 'Lunchtime Trouble Makers' is what they are commonly known as, but for Ace and Invisible it's a story of friendship and determination. -

Volume 11, Issue 4 a Collection of Writing Pieces Chosen by Erickson Students to Demonstrate Their Writing Growth Over the Course of the 2014

Volume 11, Issue 4 A collection of writing pieces chosen by Erickson students to demonstrate their writing growth over the course of the 2014- 2015 school year. The Squirrel and the Dinosaur! Fable By: Gavin Grade 5 Based off of David and Goliath! Once upon a time, a long time ago, there was a squirrel named Dave and a di- nosaur named Giant Bob. Giant Bob wants to conquer the squirrels for multiple reasons. First, they have good land. The land had plenty of trees, rocks, other animals, water, just about any- thing a dinosaur would want. Second, they taste good. What meat eating dinosaur doesn’t want a life supply of food? Third, they are easy to destroy' or are they& When the squirrels saw the dinosaur, they hid in any place they could find. (n- der trees, behind rocks, or in the leaves. With this, Giant Bob bragged. )HA-HA-HA! I will destroy you all any second and will be the greatest, most powerful, and smartest dinosaur on Earth, -ou are ants just trying to flee from me, but nobody can escape my enormous eyes. .othing can stop me,/ Dave knew that Giant Bob wasn%t no match for his weapon, God, and the faith Dave had made him even stronger. 0e was one of all the squirrels who praised God but it seemed that he was the only one who remembered his power. Dave remem- bered the stories his mother taught to him about 1dam and Eve. 0ow he created the sky, the world, the land, the sea, and all of the animals, not to mention himself. -

Lucinda Williams .Pages

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution July 12, 1998 You may not know her name. You may not have seen her face. But after hearing 'Car Wheels on a Gravel Road, ' you'll know . LUCINDA WILLIAMS By Eileen M. Drennen The perfect sound can live in your mind like a landscape you know by heart. You can circle around it, tirelessly, until maybe, just maybe, you capture it on tape. When others finally hear it, they will heap praise upon you for getting it so right. Until then, you may be dismissed as a "nutty perfectionist" by band mates or even The New York Times. And instead of talking about your music, every interviewer will want to chat about being obsessive. Welcome to Lucinda Williams' nightmare. At 45, she is revered by other musicians, critics and fans for making country blues that are closer to poetry than pop. She's never charted, and every label she's ever signed with has folded, so she's largely unknown to the average consumer of popular entertainment. "Passionate Kisses, " her most famous song, only hit country radio when Mary Chapin Carpenter covered it, winning them both a Grammy in 1994. Though her fifth album, "Car Wheels on a Gravel Road" is being greeted with raves (see ours on Page L3), it did not come without a price: three sets of producers, an ever- expanding cast of musicians, take and retake, mix and remix. The usual question is "why does Lucinda Williams take so long to make a record?" She's gladly sacrificed volume for creative control on each disc --- her last, the acclaimed "Sweet Old World, " came out in 1992. -

ENGAGE Inelegant Engagement Workshop Report

ENGAGE 2019 INELEGANCE AND WHY WE MIGHT DESIRE IT WORKSHOP REPORT Bentley Crudgington ABSTRACT In founding Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC) and the AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power (ACT-UP), Larry Kramer created two of the earliest centrally organised examples of health research engagement and public and patient involvement. These activists were not rejecting the research itself but denouncing its “elegant” nature. What would inelegant engagement look like and why might we desire it? What would it look like if we acted up and queered engagement, lavishing our time, skills, creativity and resources on the public and not researchers? This participatory workshop will explore these possibilities to produce an inelegant manifesto of change. FORMAT As an introduction to the concept of inelegance, and why we might desire it, we considered some of the inventions used by ACT UP and compared them with two current areas of social theory. We borrowed from queer theory and visual culture analysis to consider how we, as engagement professionals, frame our invitations, construct our publics and operate within institutional structures. We used these experiences to identify what systems need to be in place and which barriers need managing to allow us to become inelegant. We reviewed these ideas together and clustered them into emerging themes. We then named each cluster with an action to create an inelegant manifesto. This report summarises what we learnt together. In January 1982, Larry Kramer, a New York based writer, held a gathering of around eighty gay men at his apartment to discuss the emerging reports of a “gay cancer”.