Open Source Vendors' Business Model

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

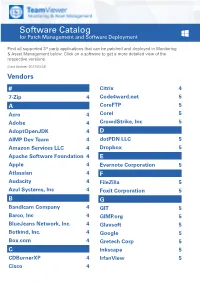

Software Catalog for Patch Management and Software Deployment

Software Catalog for Patch Management and Software Deployment Find all supported 3rd party applications that can be patched and deployed in Monitoring & Asset Management below. Click on a software to get a more detailed view of the respective versions. (Last Update: 2021/03/23) Vendors # Citrix 4 7-Zip 4 Code4ward.net 5 A CoreFTP 5 Acro 4 Corel 5 Adobe 4 CrowdStrike, Inc 5 AdoptOpenJDK 4 D AIMP Dev Team 4 dotPDN LLC 5 Amazon Services LLC 4 Dropbox 5 Apache Software Foundation 4 E Apple 4 Evernote Corporation 5 Atlassian 4 F Audacity 4 FileZilla 5 Azul Systems, Inc 4 Foxit Corporation 5 B G Bandicam Company 4 GIT 5 Barco, Inc 4 GIMP.org 5 BlueJeans Network, Inc. 4 Glavsoft 5 Botkind, Inc. 4 Google 5 Box.com 4 Gretech Corp 5 C Inkscape 5 CDBurnerXP 4 IrfanView 5 Cisco 4 Software Catalog for Patch Management and Software Deployment J P Jabra 5 PeaZip 10 JAM Software 5 Pidgin 10 Juraj Simlovic 5 Piriform 11 K Plantronics, Inc. 11 KeePass 5 Plex, Inc 11 L Prezi Inc 11 LibreOffice 5 Programmer‘s Notepad 11 Lightning UK 5 PSPad 11 LogMeIn, Inc. 5 Q M QSR International 11 Malwarebytes Corporation 5 Quest Software, Inc 11 Microsoft 6 R MIT 10 R Foundation 11 Morphisec 10 RarLab 11 Mozilla Foundation 10 Real 11 N RealVNC 11 Neevia Technology 10 RingCentral, Inc. 11 NextCloud GmbH 10 S Nitro Software, Inc. 10 Scooter Software, Inc 11 Nmap Project 10 Siber Systems 11 Node.js Foundation 10 Simon Tatham 11 Notepad++ 10 Skype Technologies S.A. -

Realvnc @ LC August 2018 LC User Meeting

RealVNC @ LC August 2018 LC User Meeting Cameron Harr Title (optional) Aug. 21, 2018 LLNL-PRES-XXXXXX This work was performed under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under contract DE-AC52-07NA27344. Lawrence Livermore National Security, LLC RealVNC @ LC § What is RealVNC? § What did we have? § What do we have now? § What’s coming in the future? § How do you use it? 2 LLNL-PRES-xxxxxx Cloud versus direct with VNC Connect VNC Connect is unique among remote access software in its ability to offer both cloud and direct connectivity methods within a single product. At first glance, knowing whether to connect directly or via our cloud service can seem confusing. However, there are clear benefits to each connection method. The trick is knowing how to maximize these benefits. This brief product guide provides an overview of the differences between cloud and direct connectivity, and offers some advice on how each method can be used to your greatest advantage. Key terminology Throughout this guide, we refer to certain RealVNC-specific terminology. VNC Connect is comprised of two separate apps: VNC Server and VNC Viewer. You must install and license VNC Server on the computer you want to control. This is known as your VNC Server computer. You must then install VNC Viewer on the computer or device you want to take control from, which is known as your VNC Viewer device. You do not need to license this device, meaning you can freely connect to your VNC Server computer from as many devices as you wish. -

Embedded Linux for Thin Clients Next Generation (Elux® NG) Version 1.25

Embedded Linux for Thin Clients Next Generation (eLux® NG) Version 1.25 Administrator’s Guide Build Nr.: 23 UniCon Software GmbH www.myelux.com eLux® NG Information in this document is subject to change without notice. Companies, names and data used in examples herein are fictitious unless otherwise noted. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, for any purpose, without the express consent of UniCon Software GmbH. © by UniCon 2005 Software GmbH. All rights reserved eLux is a registered trademark of UniCon Software GmbH in Germany. Accelerated-X is a trademark of Xi Graphics, Inc. Adobe, Acrobat Reader and PostScript are registered trademarks of Adobe Systems Incorporated in the United States and/or other countries. Broadcom is a registered trademark of Broadcom Corporation in the U.S. and/or other countries. CardOS is a registered trademark and CONNECT2AIR is a trademark of Siemens AG in Germany and/or other countries. Cisco and Aironet are registered trademarks of Cisco Systems, Inc. and/or its affiliates in the U.S. and certain other countries. Citrix, Independent Computing Architecture (ICA), Program Neighborhood, MetaFrame, and MetaFrame XP are registered trademarks or trademarks of Citrix Systems, Inc. in the United States and other countries. CUPS and the Common UNIX Printing System are the trademark property of Easy Software Products. DivX is a trademark of Project Mayo. Ericom and PowerTerm are registered trademarks of Ericom Software in the United States and/or other countries. Gemplus is a registered trademark and GemSAFE a trademark of Gemplus. -

Crowdsourcing: Today and Tomorrow

Crowdsourcing: Today and Tomorrow An Interactive Qualifying Project Submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science by Fangwen Yuan Jun Liang Zhaokun Xue Approved Professor Sonia Chernova Advisor 1 Abstract This project focuses on crowdsourcing, the practice of outsourcing activities that are traditionally performed by a small group of professionals to an unknown, large community of individuals. Our study examines how crowdsourcing has become an important form of labor organization, what major forms of crowdsourcing exist currently, and which trends of crowdsourcing will have potential impacts on the society in the future. The study is conducted through literature study on the derivation and development of crowdsourcing, through examination on current major crowdsourcing platforms, and through surveys and interviews with crowdsourcing participants on their experiences and motivations. 2 Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 8 1.1 Definition of Crowdsourcing ............................................................................................................... 8 1.2 Research Motivation ........................................................................................................................... 8 1.3 Research Objectives ........................................................................................................................... -

The GNU Configure and Build System

The GNU configure and build system Ian Lance Taylor Copyright c 1998 Cygnus Solutions Permission is granted to make and distribute verbatim copies of this manual provided the copyright notice and this permission notice are preserved on all copies. Permission is granted to copy and distribute modified versions of this manual under the con- ditions for verbatim copying, provided that the entire resulting derived work is distributed under the terms of a permission notice identical to this one. Permission is granted to copy and distribute translations of this manual into another lan- guage, under the above conditions for modified versions, except that this permission notice may be stated in a translation approved by the Free Software Foundation. i Table of Contents 1 Introduction ............................... 1 1.1 Goals................................................... 1 1.2 Tools ................................................... 1 1.3 History ................................................. 1 1.4 Building ................................................ 2 2 Getting Started............................ 3 2.1 Write configure.in ....................................... 4 2.2 Write Makefile.am ....................................... 6 2.3 Write acconfig.h......................................... 7 2.4 Generate files ........................................... 8 2.5 Example................................................ 8 2.5.1 First Try....................................... 9 2.5.2 Second Try.................................... 10 2.5.3 Third -

Running Windows Programs on Ubuntu with Wine Wine Importer Shanna Korby, Fotolia

KNoW-HoW Wine Running Windows programs on Ubuntu with Wine Wine importer Shanna Korby, Fotolia Korby, Shanna Users who move from Windows to Ubuntu often miss some of their favorite programs and games. Wouldn’t it be practical to run Windows applications on the free Ubuntu operating system? Time for a little taste of Wine. BY TIM SCHÜRMANN any Ubuntu migrants miss to develop something similar for Linux. Box or VMware, Wine does not emulate games and graphics programs A short while later, the first version of a whole PC and thus cannot be consid- Msuch as CorelDRAW or prod- Wine was released. Today, more than ered a real emulator. This also explains ucts such as Adobe Photoshop. The only 300 volunteer programmers from all over the name Wine, which means Wine Is solution is to install Windows parallel to the world continue to contribute to the Not an Emulator. Ubuntu – or try Wine, which tricks ap- Wine project. Because of the way Wine works, it of- plications into believing they are run- fers a number of advantages. Chiefly, ning on a Windows system. What’s in a Name? you do not need an expensive Windows The history of Wine goes back to the To run Windows programs on Ubuntu, license. Programs will run almost as fast year 1993. At the time, Sun developed a Wine uses a fairly complex trick: It sits as on the Redmond operating system, small tool to run Windows applications between the Windows application and and windows behave as if they belong on its own Solaris operating system, Ubuntu like a simultaneous interpreter. -

Cygwin User's Guide

Cygwin User’s Guide Cygwin User’s Guide ii Copyright © Cygwin authors Permission is granted to make and distribute verbatim copies of this documentation provided the copyright notice and this per- mission notice are preserved on all copies. Permission is granted to copy and distribute modified versions of this documentation under the conditions for verbatim copying, provided that the entire resulting derived work is distributed under the terms of a permission notice identical to this one. Permission is granted to copy and distribute translations of this documentation into another language, under the above conditions for modified versions, except that this permission notice may be stated in a translation approved by the Free Software Foundation. Cygwin User’s Guide iii Contents 1 Cygwin Overview 1 1.1 What is it? . .1 1.2 Quick Start Guide for those more experienced with Windows . .1 1.3 Quick Start Guide for those more experienced with UNIX . .1 1.4 Are the Cygwin tools free software? . .2 1.5 A brief history of the Cygwin project . .2 1.6 Highlights of Cygwin Functionality . .3 1.6.1 Introduction . .3 1.6.2 Permissions and Security . .3 1.6.3 File Access . .3 1.6.4 Text Mode vs. Binary Mode . .4 1.6.5 ANSI C Library . .4 1.6.6 Process Creation . .5 1.6.6.1 Problems with process creation . .5 1.6.7 Signals . .6 1.6.8 Sockets . .6 1.6.9 Select . .7 1.7 What’s new and what changed in Cygwin . .7 1.7.1 What’s new and what changed in 3.2 . -

Virtualgl / Turbovnc Survey Results Version 1, 3/17/2008 -- the Virtualgl Project

VirtualGL / TurboVNC Survey Results Version 1, 3/17/2008 -- The VirtualGL Project This report and all associated illustrations are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Any works which contain material derived from this document must cite The VirtualGL Project as the source of the material and list the current URL for the VirtualGL web site. Between December, 2007 and March, 2008, a survey of the VirtualGL community was conducted to ascertain which features and platforms were of interest to current and future users of VirtualGL and TurboVNC. The larger purpose of this survey was to steer the future development of VirtualGL and TurboVNC based on user input. 1 Statistics 49 users responded to the survey, with 32 complete responses. When listing percentage breakdowns for each response to a question, this report computes the percentages relative to the total number of complete responses for that question. 2 Responses 2.1 Server Platform “Please select the server platform(s) that you currently use or plan to use with VirtualGL/TurboVNC” Platform Number of Respondees (%) Linux/x86 25 / 46 (54%) ● Enterprise Linux 3 (x86) 2 / 46 (4.3%) ● Enterprise Linux 4 (x86) 5 / 46 (11%) ● Enterprise Linux 5 (x86) 6 / 46 (13%) ● Fedora Core 4 (x86) 1 / 46 (2.2%) ● Fedora Core 7 (x86) 1 / 46 (2.2%) ● Fedora Core 8 (x86) 4 / 46 (8.7%) ● SuSE Linux Enterprise 9 (x86) 1 / 46 (2.2%) 1 Platform Number of Respondees (%) ● SuSE Linux Enterprise 10 (x86) 2 / 46 (4.3%) ● Ubuntu (x86) 7 / 46 (15%) ● Debian (x86) 5 / 46 (11%) ● Gentoo (x86) 1 / -

Comércio Eletrônico

Comércio Eletrônico Aula 1 - Overview of Electronic Commerce Learning Objectives 1. Define electronic commerce (EC) and describe its various categories. 2. Describe and discuss the content and framework of EC. 3. Describe the major types of EC transactions. 4. Describe the drivers of EC. 5. Discuss the benefits of EC to individuals, organizations, and society. 6. Discuss social computing. 7. Describe social commerce and social software. 8. Understand the elements of the digital world. 9. Describe some EC business models. 10. List and describe the major limitations of EC. Case: Starbucks Electronic Commerce (EC) EC refers to using the Internet and other networks (e.g., intranets) to purchase, sell, transport, or trade data, goods, or services. e-Business • Narrow definition of EC: buying and selling transactions between business partners. • e-Business refers to a broader definition of EC: – buying and selling of goods and services – Servicing customers – collaborating with business partners, – delivering e-learning, – conducting electronic transactions within organizations. – Among others e-Business Note: some view e-business only as comprising those activities that do not involve buying or selling over the Internet, i.e., a complement of the narrowly defined EC. Major EC Concepts: Non-EC vs. Pure EC vs. Partial EC • EC three major activities: – ordering and payments, – order fulfilment, and – delivery to customers. • pure EC: all activities are digital, • non-EC: none are digital, • otherwise, we have partial EC. Major EC Concepts: Pure -

Producing Open Source Software How to Run a Successful Free Software Project

Producing Open Source Software How to Run a Successful Free Software Project Karl Fogel Producing Open Source Software: How to Run a Successful Free Software Project by Karl Fogel Copyright © 2005-2018 Karl Fogel, under the CreativeCommons Attribution-ShareAlike (4.0) license. Version: 2.3098 Home site: http://producingoss.com/ Dedication This book is dedicated to two dear friends without whom it would not have been possible: Karen Under- hill and Jim Blandy. i Table of Contents Preface ............................................................................................................................. vi Why Write This Book? ............................................................................................... vi Who Should Read This Book? .................................................................................... vii Sources ................................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements ................................................................................................... viii For the first edition (2005) ................................................................................ viii For the second edition (2017) ............................................................................... x Disclaimer .............................................................................................................. xiii 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... -

Linux at 25 PETERHISTORY H

Linux at 25 PETERHISTORY H. SALUS Peter H. Salus is the author of A n June 1991, at the USENIX conference in Nashville, BSD NET-2 was Quarter Century of UNIX (1994), announced. Two months later, on August 25, Linus Torvalds announced Casting the Net (1995), and The his new operating system on comp.os.minix. Today, Android, Google’s Daemon, the Gnu and the Penguin I (2008). [email protected] version of Linux, is used on over two billion smartphones and other appli- ances. In this article, I provide some history about the early years of Linux. Linus was born into the Swedish minority of Finland (about 5% of the five million Finns). He was a “math guy” throughout his schooling. Early on, he “inherited” a Commodore VIC- 20 (released in June 1980) from his grandfather; in 1987 he spent his savings on a Sinclair QL (released in January 1984, the “Quantum Leap,” with a Motorola 68008 running at 7.5 MHz and 128 kB of RAM, was intended for small businesses and the serious hobbyist). It ran Q-DOS, and it was what got Linus involved: One of the things I hated about the QL was that it had a read-only operating system. You couldn’t change things ... I bought a new assembler ... and an editor.... Both ... worked fine, but they were on the microdrives and couldn’t be put on the EEPROM. So I wrote my own editor and assembler and used them for all my programming. Both were written in assembly language, which is incredibly stupid by today’s standards. -

FLOSS Final Report – Part 3 Free/Libre Open Source Software: Survey and Study

FLOSS Final Report – Part 3 Free/Libre Open Source Software: Survey and Study Basics of Open Source Software Markets and Business Models Berlin, July 2002 3 BERLECON RESEARCH GmbH Oranienburger Str. 32 10117 Berlin Tel.: +49 30 285296-0 Fax: +49 30 285296-29 Web: http://www.berlecon.de Email: [email protected] Acknowledgements: This work was prepared by Dorit Spiller and Thorsten Wichmann from Berlecon Research. It is part of the final report for the project „FLOSS – Free/Libre Open Source Software: Survey and Study“, which was financed under the European Com- mission‘s IST programme, key action 4 as accompanying measure (IST-2000-4.1.1). Disclaimer: The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily re- flect those of the European Commission. Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use that might be made of the following information. Nothing in this report implies or expresses a warranty of any kind. Results from this report should only be used as guidelines as part of an overall strategy. For detailed ad- vice on corporate planning, business processes and management, technology integra- tion and legal or tax issues, the services of a professional should be obtained. Names and trademarks mentioned in the report are the property of their respective owners. © 2002 by Berlecon Research GmbH. 4 V 1.1 - 020905 © 2002 by Berlecon Research GmbH. 5 Table of contents 1 Introduction....................................................................................................... 9 2 Software and the Open Source phenomenon.................................................... 11 2.1 The Open Source phenomenon .................................................................