Compassionate Neo-Traditionalism in Hosoda Mamoru's Animation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Program (PDF)

ヴ ィ ボー ・ ア ニ メー シ カ ョ ワ ン イ フ イ ェ と ス エ ピ テ ッ ィ Viborg クー バ AnimAtion FestivAl ル Kawaii & epikku 25.09.2017 - 01.10.2017 summAry 目次 5 welcome to VAF 2017 6 DenmArk meets JApAn! 34 progrAmme 8 eVents Films For chilDren 40 kAwAii & epikku 8 AnD families Viborg mAngA AnD Anime museum 40 JApAnese Films 12 open workshop: origAmi 42 internAtionAl Films lecture by hAns DybkJær About 12 important ticket information origAmi 43 speciAl progrAmmes Fotorama: 13 origAmi - creAte your own VAF Dog! 44 short Films • It is only possible to order tickets for the VAF screenings via the website 15 eVents At Viborg librAry www.fotorama.dk. 46 • In order to pick up a ticket at the Fotorama ticket booth, a prior reservation Films For ADults must be made. 16 VimApp - light up Viborg! • It is only possible to pick up a reserved ticket on the actual day the movie is 46 JApAnese Films screened. 18 solAr Walk • A reserved ticket must be picked up 20 minutes before the movie starts at 50 speciAl progrAmmes the latest. If not picked up 20 minutes before the start of the movie, your 20 immersion gAme expo ticket order will be annulled. Therefore, we recommended that you arrive at 51 JApAnese short Films the movie theater in good time. 22 expAnDeD AnimAtion • There is a reservation fee of 5 kr. per order. 52 JApAnese short Film progrAmmes • If you do not wish to pay a reservation fee, report to the ticket booth 1 24 mAngA Artist bAttle hour before your desired movie starts and receive tickets (IF there are any 56 internAtionAl Films text authors available.) VAF sum up: exhibitions in Jane Lyngbye Hvid Jensen • If you wish to see a movie that is fully booked, please contact the Fotorama 25 57 Katrine P. -

Tuesday 12 April 2016, London. This June, Audiences at BFI Southbank Will Be Enchanted by the Big-Screen Thrills of Steven Spie

WITH ONSTAGE APPEARANCES FROM: DIRECTORS CRISTI PUIU, RADU JUDE, ANCA DAMIAN, TUDOR GIURGIU, RADU MUNTEAN AND MICHAEL ARIAS; BROADCASTERS MARK KERMODE AND JONATHAN MEADES Tuesday 12 April 2016, London. This June, audiences at BFI Southbank will be enchanted by the big-screen thrills of Steven Spielberg as we kick off a two month season, beginning on Friday 27 May with a re-release of the sci-fi classic Close Encounters of the Third Kind (Director’s Cut) (1977) in a brand new 35mm print, exclusively at BFI Southbank. We also welcome the most exciting talent behind the ‘New Wave’ of Romanian cinema to BFI Southbank, including directors Cristi Puiu and Radu Jude, as we celebrate this remarkable movement in world cinema with a dedicated season Revolution In Realism: The New Romanian Cinema. The BFI’s ever popular Anime Weekend returns to BFI Southbank from 3-5 June with the best new films from the genre, while this month’s television season is dedicated to Architecture on TV, with onscreen appearance from JG Ballard, Iain Nairn and Raymond Williams. The events programme for June boasts film previews of Notes on Blindness (Pete Middleton, James Spinney, 2016) and Race (Stephen Hopkins, 2016), and a TV preview of the new BBC drama The Living and the Dead starring Colin Morgan and Charlotte Spencer. New releases will include the Oscar-nominated Embrace of the Serpent (Ciro Guerra, 2015) and Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s latest film Cemetery of Splendour (2015). The BFI’s new Big Screen Classics series offers films that demand the big-screen treatment, and this month include The Night of the Hunter (Charles Laughton, 1955), Once Upon a Time in the West (Sergio Leone, 1968) and Days of Heaven (Terrence Malick, 1978). -

Aproximaciones Al Anime: Producción, Circulación Y Consumo

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by El Servicio de Difusión de la Creación Intelectual Vol. 1, N.º 51 (julio-septiembre 2016) Aproximaciones al anime: producción, circulación y consumo en el siglo XXI Analia Lorena Meo Facultad de Ciencias Sociales; Universidad de Buenos Aires (Argentina) Resumen En este escrito se realizó una aproximación al anime (アニメ‘animación japonesa’) presentando brevemente tres fases relacionadas entre sí: producción, circulación y consumo de este lenguaje y producto cultural contemporáneo. Se efectuó una entrada a este mundo animado nipón mediante sus diferentes definiciones y concepciones, su creación a través de las compañías de animación, la posterior distribución mediante distintos medios de comunicación masivos y el consumo pasivo y activo de los otaku (オタク) tanto en la Argentina como en diversas partes del mundo. Se hizo hincapié en la apertura que produjeron los avances tecnológicos para el aumento de la recepción de este bien contemporáneo, la modificación de la forma de consumo y el incremento del interés sobre este fenómeno por parte de académicos en todo el Globo. Palabras clave: anime; estudios de animación; distribución; otaku; Argentina. Artículo recibido: 20/07/16; evaluado: entre 20/07/16 y 25/08/16; aceptado: 12/09/16. Twenty years ago, any non-Japanese encountering the words “anime” or “manga” would have shaken their heads in puzzlement. Flash forward to the twenty-first century, and we find a world where anime and manga are ubiquitous, known and loved around the globe from South Africa to Latin America. -

… … Mushi Production

1948 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 … Mushi Production (ancien) † / 1961 – 1973 Tezuka Productions / 1968 – Group TAC † / 1968 – 2010 Satelight / 1995 – GoHands / 2008 – 8-Bit / 2008 – Diomédéa / 2005 – Sunrise / 1971 – Deen / 1975 – Studio Kuma / 1977 – Studio Matrix / 2000 – Studio Dub / 1983 – Studio Takuranke / 1987 – Studio Gazelle / 1993 – Bones / 1998 – Kinema Citrus / 2008 – Lay-Duce / 2013 – Manglobe † / 2002 – 2015 Studio Bridge / 2007 – Bandai Namco Pictures / 2015 – Madhouse / 1972 – Triangle Staff † / 1987 – 2000 Studio Palm / 1999 – A.C.G.T. / 2000 – Nomad / 2003 – Studio Chizu / 2011 – MAPPA / 2011 – Studio Uni / 1972 – Tsuchida Pro † / 1976 – 1986 Studio Hibari / 1979 – Larx Entertainment / 2006 – Project No.9 / 2009 – Lerche / 2011 – Studio Fantasia / 1983 – 2016 Chaos Project / 1995 – Studio Comet / 1986 – Nakamura Production / 1974 – Shaft / 1975 – Studio Live / 1976 – Mushi Production (nouveau) / 1977 – A.P.P.P. / 1984 – Imagin / 1992 – Kyoto Animation / 1985 – Animation Do / 2000 – Ordet / 2007 – Mushi production 1948 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 … 1948 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 … Tatsunoko Production / 1962 – Ashi Production >> Production Reed / 1975 – Studio Plum / 1996/97 (?) – Actas / 1998 – I Move (アイムーヴ) / 2000 – Kaname Prod. -

Lupine Loss and the Liquidation of the Nuclear Family in Mamoru Hosoda’S Wolf Children (2012) Dr

Journal of Anime and Manga Studies Volume 1 ‘Wolves or People?’: Lupine Loss and the Liquidation of the Nuclear Family in Mamoru Hosoda’s Wolf Children (2012) Dr. David John Boyd Volume 1, Pages 1-34 Abstract: This essay examines an alternative eco-familial reading of Mamoru Hosoda’s manga film, Wolf Children (2012) through an analysis of Japanese extinction anxieties further exacerbated by 3/11. By reading the film through a minor history of the extinction of the Honshu wolf as a metaphor for 3/11, I argue that an examination of the degradation of Japanese preindustrial “stem family” and the fabulative expression of species cooperation and hybridity can more effectively be framed by the popular Japanese imaginary as a lupine apocalypse. In a reading of Deleuze and Guattari on becoming-animal, the omnipresence of lupine loss in the institutions of the home, work, and schools of contemporary Japan, interrogated in many manga, anime, and video game series like Wolf Children, further reveals the ambivalence of post-3/11 artists as they approach family and the State in seeking out more nonhuman depictions of Japan. In this reading of becoming-wolf, Hosoda’s resituates the family/fairy-tale film as a complex critique of the millennial revival of a nuclear Japan in the age of economic and environmental precarity and collapse. I hope to explore the nuances and contradictions of Hosoda’s recapitulation of family through a celebration of Deleuzo-Guattarian pack affects and an introduction of the possibilities of “making kin,” as Donna Haraway explains, at the ends of the Anthropocene. -

Russian Japanology Review 2020

RUSSIAN JAPANOLOGY REVIEW 2020. Vol. 3 (No. 2) REVIEW JAPANOLOGY RUSSIAN 2020. Vol. 3(No. 2020. Vol. I SSN: 2658-6444 2) Association of Japanologists of Russia Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences RUSSIAN JAPANOLOGY REVIEW 2020. Vol. 3 (No. 2) MOSCOW Editors Streltsov D. V. Doctor of Sciences (History), Professor, Head of Department of Afro-Asian Studies, MGIMO-University, Chairman of the Association of Japanologists of Russia Grishachev S. V. Ph.D. (History), Associate professor, School of Asian Studies, HSE Universlty, Executive secretary of the Association of Japanologists of Russia With compliment to Japan Foundation and The International Chodiev Foundation. Russian Japanology Review, 2020. Vol. 3 (No. 2). 152 p. The Russian Japanology Review is a semiannual edition. This edition is published under the auspices of the Association of Japanologists in cooperation with the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS). The purpose of this project is broader international promotion of the results of Japanese Studies in Russia and the introduction of the academic activities of Russian Japanologists. E-mail: [email protected] Web sites: www.japanstudies.ru www.japanreview.ru ISSN: 2658-6789 (print) ISSN: 2658-6444 (e-book) © Association of Japanologists of Russia, 2020. © Institute of Oriental Studies of RAS, 2020. © Grishachev S., photo, 2020. CONTENT Panov A. N. The Soviet-Japanese Joint Declaration of 1956: a Difficult Path to Signing, a Difficult Fate after Ratification ............................ 5 Katasonova E. L. Japanese Prisoners of War in the USSR: Facts, Versions, Questions ..................................... 52 Dyachkov I. V. Collective Memory and Politics: ‘Comfort Women’ in Current Relations between South Korea and Japan .............................................................. -

Mamoru Hosoda and His Humanistic Animations

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE 79 Mamoru Hosoda and His Humanistic Animations Satoshi TSUKAMOTO 愛知大学国際コミュニケーション学部 Faculty of International Communication, Aichi University E-mial: [email protected] 概 要 本論文は、日本のアニメーションの監督である細田守の作品を考察する。彼のアニメーショ ンには、筆者によると二つの特徴がある。一つ目は人と人とのつながりが大切であるというメッ セージを、細田はアニメーションを通して伝えている。人と人とのつながりは、家族ばかりで なく、親戚、友人、隣人、師弟を含んでいる。作品によって人と人との関係性は違うが、その 重要性を彼の作品は伝えている。二つ目は異次元の世界をうまく描いているという点である。 インターネットの世界と現実、人間とオオカミ、人間と化け物などの二つの次元の違う世界を 相対立する世界というより、共存する世界として描いている。この二つの点が細田守のアニメー ションの特徴である。 Introduction Japanese animations are popular not only domestically but also globally. The wide variety of animations ranges from family-oriented TV animations such as Sazae San (1968–the present) and Chibi Maruko-chan (1990–1992, 1995–the present) to science fiction animations, such as Appleseed (2004) and PSYCHO-PASS (2015). Because of the Internet it is easy to gain access anywhere to the contents of Japanese animations 80 文明21 No.42 with provocative themes, and this situation contributes to their popularity (Otmazgin, 2014). The first animation appearing on TV in Japan was Astro Boy, created by Osamu Tezuka in 1963. Then, an epoch-making animation that surprised audiences throughout the world, Akira, was produced by Katsuhiko Otomo in 1988. In my generation (i.e., born in the 1960s), many people grew up with animations, starting with the TV series, Space Battleship Yamato (1974–1975). Lupin the Third: The Castle of Cagliostro (1979) and Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind (1984) followed, both of which were directed by Hayao Miyazaki. Of course, I watched more animations in my school days. In fact, many people, including me, have been influenced by certain animations in their youth in one way or another. -

Wolf Children

PRESENTS WOLF CHILDREN A MAMORU HOSODA FILM Running time: 117 minutes Certificate: TBC Opens at UK cinemas on 25th October Press Contacts Elle McAtamney – [email protected] For hi-res images/production notes and more, go to – www.fetch.fm To the children, a movie like a delightful, fun fairy tale… To the youth, to make raising children, which they have yet to experience, seem full of surprises and wonder… And to the parents, to let them reminisce about their children’s growth… I am striving to make an invigorating movie that satisfies the principles of entertainment. Mamoru Hosoda Director, screenwriter, author of original story INTRODUCTION The long-awaited new film by Director Mamoru Hosoda! Yet another movie that enthralls people of all generations!! In “The Girl Who Leapt Through Time” (2006), he depicted the radiance of youth in flashing moments of life. In “SUMMER WARS” (2009), he told a story about a miracle, of how the bond between people saved Earth’s crisis, and the film swept awards domestic and abroad. Mamoru Hosoda has become the most noted animation director in the world. Why do his works appeal to people of all generations? His stories are not about the extraordinary, and they are not about superheroes. Set in towns that could really exist, the main characters are surrounded by ordinary people and are troubled by slightly unique circumstances, which they struggle to overcome. Based on well-thought-out scenarios, these real-to-life stories are made into dynamic animation. That’s why the main characters seem so familiar to us and draw our sympathy, and we get excited watching how they fare. -

El Anime De Los Noventa Como Un Reflejo De La Interacción Entre El Hombre/Usuario E Internet

UNIVERSIDAD JUAN AGUSTÍN MAZA FACULTAD DE PERIODISMO LICENCIATURA EN COMUNICACIÓN SOCIAL DE LO FANTÁSTICO A LO REAL: EL ANIME DE LOS NOVENTA COMO UN REFLEJO DE LA INTERACCIÓN ENTRE EL HOMBRE/USUARIO E INTERNET Alumna: Lourdes Micaela Arrieta Tutor disciplinario: Lic. Andrea Ginestar Tutor metodológico: Lic. Guillermo Gallardo MENDOZA 2016 Mediante la presente tesina y la defensa del mismo aspiro al título de Licenciatura en Comunicación Social. Alumno: Lourdes Micaela Arrieta DNI: 37.298.417 Matrícula: 2.029 Fecha del examen final: Docentes del Tribunal Evaluador: Calificación: Lourdes Micaela Arrieta I DEDICATORIA “Entonces, cuando aprendió a navegar por la Red, nuestro mundo se derrumbó. Se dejó llevar por los signos calientes y empezó conocer sin caras. Los perfiles adúlteros de los espectros femeninos (y si es que los eran), condujeron a desconocernos. Fue, cuando como espías cibergálacticos, incursionamos (los tres) a engañar a las maestras de la seducción virtual. ¡Qué fácil era embaucar con datos falsos las ilusiones de las destructoras de familias! Parece ser, son las mujeres de entre 40 y 50 años de viejas, las que se registran para jugar a los detestables clicks en los “gatos” (o chats) y las redes sociales (no lo sé, me imagino una red pesquera y alrededor cientos de individuos, en un mismo bote, todos hablándole a la mar) y pretenden, quizá, escapar de sus maridos, sus hijos u otro contacto ‘romántico’. No le hallo la gracia… De adolescente me pasaba un largo rato en Internet; indagaba cómo burlar los datos, aunque no son conocimientos de un hacker, es más básico. Pensándolo bien, no logro comprender el dolor de ella, ante semejantes artimañas de él, y tampoco de él, el querer abandonarnos por signos efímeros y ¿reales? Lo cierto, es que con mi hermano llorábamos muy mucho. -

Anime Fusion Will Return! Year 9: “Trick Or Treat” October 16-18, 2020 Crowne Plaza Minneapolis West

Welcome General Information Operations, Parking, Shuttle, Concessions ................................................. 2 Registration, Volunteers, Con Fuel ................................................................. 3 Activity Information Club Fusion, Photoshoots, Cosplay Lounge, Family Activity Room, Quiet Zone, Merchandise ...................................... 4 Room Parties, Karma Café, Manga Library ..................................................... 5 Masquerade Cosplay Competition ..................................................................... 6 Vendor Information Artist Alley, Dealers Room, Ambassador Row ............................................. 7 Guest Information Guests of Honor ........................................................................................................... 8 Featured Speakers .......................................................................................................... 9 Dance DJs ......................................................................................................................... 11 Autograph Sessions, Charity Auctions ........................................................ 12 Special Features Maid Cafe, Swap Meet ................................................................................................ 14 Community Rooms, Boffer Foam Fighting ................................................. 15 Gaming Rooms Tabletop Gaming .......................................................................................................... 16 Video -

![REVISTA ECOS DE ASIA / Nº 23] Enero De 2016](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0035/revista-ecos-de-asia-n%C2%BA-23-enero-de-2016-3770035.webp)

REVISTA ECOS DE ASIA / Nº 23] Enero De 2016

[REVISTA ECOS DE ASIA / Nº 23] Enero de 2016 REVISTA ECOS DE ASIA /revistacultural.ecosdeasia.com / ENERO 2016 Página 1 [REVISTA ECOS DE ASIA / Nº 23] Enero de 2016 Presentación Iniciamos el año 2016 con la ilusión intrínseca a todo nuevo comienzo y con la confianza de seguir ÍNDICE DE CONTENIDOS ofreciendo artículos de calidad que sacien vuestro interés sobre la cultura asiática. La primera semana Historia y Pensamiento del año tiene en España un carácter muy especial, Contra el Tigre de Papel: Mao Zedong y el maoísmo vinculado al mundo de la infancia, por lo que desde (II). Por Pablo M. Somoano 4 Ecos de Asia quisimos preparar la llegada de Sus Majestades los Reyes Magos de Oriente con una Muñecas como embajadoras de la paz. El caso de las serie de artículos que nos ayudaron a conectar con Friendship Dolls. Por María Gutiérrez. 9 nuestro niño interior y a recuperar recuerdos infantiles. De esta forma, Carolina Plou Anadón nos habló sobre el regreso de la afamada serie Digimon, Arte además de continuar con la quinta entrega de su serie Aprendiendo Asia, dedicada a la ochentera La obra La pittura moderna giapponese (1930) de serie de animación Jem y los Hologramas. Esta Pietro Silvio Rivetta. Por Pilar Araguás. 14 misma colaboradora dio inicio a una nueva serie de artículos destinados a analizar la presencia oriental El neosurrealismo en el Sudeste Asiático: Vida y obra de Nguyen Dinh Dang II (Japón: libertad y crítica). Por en los álbumes de cromos de Nestlé de los años Andrea García. 18 treinta y sesenta. -

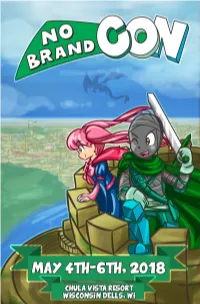

No Brand Con 2018 Program Guide

1 Table of Contents Welcome 04 Convention Rules 06 Guests 09 Artist Alley 18 Vendor Room 20 Merchandise 22 Schedule 24 Main Events 30 Panels 34 No Mercy Room 40 Anime Room 44 Video Game Room 48 Tabletop Gaming Room 50 Puzzle Hunt 52 Food Near the Chula Vista 54 FAQs 55 Convention Maps 56 Registration Table Friday: 10am - 9pm Saturday: 9am - 9pm Sunday: 9am - 1pm For off-hour registration, lost badges, or questions regarding registration, you can visit the Staff Room (Sierra Vista). Location is on our floor map in the back of this book. Special thanks to Cassafrass (fb.com/CassafrassCosplay) for our amazing Cover Art! 3 Welcome to No Brand Con 2018 Letter From The Directors! Hello and welcome to No Brand Con 17! Not only is it our 17th consecutive year, but our third here at the Chula Vista Resort. We have worked tirelessly to ensure this year will be our best yet- but we couldn’t have done it alone! We have an amazing staff to thank that has put in countless hours, fantastic hotel staff to help us out, our most gracious spon- sors, and let’s not forget the most important people of all- YOU! From our fans who have been here from the beginning to those of you joining us for the first time and everyone in between, thank you for supporting No Brand Con through the years. This year we are fortunate enough to welcome back staff that have been with No Brand since day one, and we couldn’t be more excited to merge the old and the new.