Mark Twain, Richard Irving Dodge, and the Indian: Myth and Disillusionment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commonlit | Excerpts from Roughing It

Name: Class: Excerpts from Roughing It By Mark Twain 1872 Samuel Clemens (1835-1910), recognized by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American author and humorist. Roughing It, his second published book, is a semi-autobiographical, humorous collection of stories loosely based on Twain’s actual travels through the “Wild West” from 1861-1866. Twain had traveled west to find work and escape fighting during the Civil War. The protagonist, presented as a young Twain, recounts his adventures as a naïve and inexperienced easterner, during the beginning of his time out West. As you read, take notes on how Twain narrates his own experiences to create a comic effect. Prefatory [1] This book is merely a personal narrative, and not a pretentious history or a philosophical dissertation.1 It is a record of several years of variegated vagabondizing,2 and its object is rather to help the resting reader while away an idle hour than afflict him with metaphysics, or goad him with science. Still, there is information in the volume; information concerning an interesting episode in the history of the Far West3, about which no books have been written by persons "Mark Twain worked here as a reporter in 1863: Territorial who were on the ground in person, and saw the Enterprise Office, Virginia City, Nevada." by Kent Kanouse is happenings of the time with their own eyes. I licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0. allude4 to the rise, growth and culmination of the silver-mining fever in Nevada — a curious episode, in some respects; the only one, of its peculiar kind, that has occurred in the land; and the only one, indeed, that is likely to occur in it. -

"Prisoners of the Caucasus: Literary Myths and Media Representations of the Chechen Conflict" by H

University of California, Berkeley Prisoners of the Caucasus: Literary Myths and Media Representations of the Chechen Conflict Harsha Ram Berkeley Program in Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies Working Paper Series This PDF document preserves the page numbering of the printed version for accuracy of citation. When viewed with Acrobat Reader, the printed page numbers will not correspond with the electronic numbering. The Berkeley Program in Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies (BPS) is a leading center for graduate training on the Soviet Union and its successor states in the United States. Founded in 1983 as part of a nationwide effort to reinvigorate the field, BPSs mission has been to train a new cohort of scholars and professionals in both cross-disciplinary social science methodology and theory as well as the history, languages, and cultures of the former Soviet Union; to carry out an innovative program of scholarly research and publication on the Soviet Union and its successor states; and to undertake an active public outreach program for the local community, other national and international academic centers, and the U.S. and other governments. Berkeley Program in Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies University of California, Berkeley Institute of Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies 260 Stephens Hall #2304 Berkeley, California 94720-2304 Tel: (510) 643-6737 [email protected] http://socrates.berkeley.edu/~bsp/ Prisoners of the Caucasus: Literary Myths and Media Representations of the Chechen Conflict Harsha Ram Summer 1999 Harsha Ram is an assistant professor in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures at UC Berkeley Edited by Anna Wertz BPS gratefully acknowledges support from the National Security Education Program for providing funding for the publication of this Working Paper . -

Gender and Ethnocentrism in Roman Accounts of Germany

Studies in Mediterranean Antiquity and Classics Volume 1 Imperial Women Issue 1 Article 6 November 2006 Primitive or Ideal? Gender and Ethnocentrism in Roman Accounts of Germany Maggie Thompson Macalester College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/classicsjournal Recommended Citation Thompson, Maggie (2006) "Primitive or Ideal? Gender and Ethnocentrism in Roman Accounts of Germany," Studies in Mediterranean Antiquity and Classics: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/classicsjournal/vol1/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Classics Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Mediterranean Antiquity and Classics by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thompson: Gender and Ethnocentrism in Roman Accounts of Germany Primitive or Ideal? Gender and Ethnocentrism in Roman Accounts of Germany Maggie Thompson For a woman who sells her chastity there is no pardon; neither beauty nor youth, nor wealth can find her a husband. For in Germany no one laughs at vice, nor calls mutual corruption “the spirit of the age.” (Tacitus, Germania, 19) It may be tempting to use quotes such as the one above to make inferences about what life must have been like for the German women Tacitus wrote about. However, ethnographies such as the Germania are more useful in garnering information about Tacitus’ Rome than they are accurate accounts of Roman Germany. When constructing the cultural geography of the world they lived in, the Romans often defined themselves, like the Greeks before them, in contrast to a cultural “Other” or “barbarian.” This dichotomy between Roman and non-Roman, West and East, civilized and uncivilized, is a regular theme throughout Classical literature and art. -

Thomposn Twain Lecture

“An American Cannibal at Home”: Comic Diplomacy in Mark Twain’s Hawai’i Todd Nathan Thompson May 23, 2018 “An American Cannibal at Home” “The new book is to be an account of travel at home, describing in a humorous and satirical way our cities and towns, and the people of different sections. No doubt the volume will be very droll, and largely infused with the shrewd common sense and eccentric mode of thought for which the author has become famous.”—Chicago Republican, August 28, 1870 Twain’s Hawai’i Writings Sacramento Union (1866) New York Tribune (1873) Lectures, sometimes titled “Our Fellow Savages of the Sandwich Islands” (1866-1873) Roughing It (1872) Following the Equator (1897) Unfinished novel (1884) Tonight ’s un-earnest analysis I will talk about how Twain: 1) Parodied travel writing, travel writers, and tourists in general 2) Set himself up as a classic comic fool and rogue (including as a cannibal) 3) Created comic comparisons of Hawaiian and American cultural and political norms that tend towards cultural relativism 4) Used caustic irony in self-undoing, “fake” proclamations of imperialism Some previous scholarship on Twain’s Hawai’i James Caron, Mark Twain, Unsanctified Newspaper Reporter (2008) Jeffrey Alan Melton, Mark Twain, Travel Books, and Tourism: The Tide of a Great Popular Movement (2002) Amy Kaplan, “Imperial Triangles: Mark Twain’s Foreign Affairs” (1997) Don Florence, Persona and Humor in Mark Twain’s Early Writings (1995) Franklin Rogers, “Burlesque Travel Literature and Mark Twain’s Roughing It” (1993) Walter Francis Frear, Mark Twain and Hawaii (1947) Savage Laughter: Nineteenth-Century American Humor and the Pacific "Jonathan's Talk With The King of the Sandwich Islands: Or Young American Diplomacy.” Yankee-Notions, February 1, 1854. -

Warriors As the Feminised Other

Warriors as the Feminised Other The study of male heroes in Chinese action cinema from 2000 to 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Chinese Studies at the University of Canterbury by Yunxiang Chen University of Canterbury 2011 i Abstract ―Flowery boys‖ (花样少年) – when this phrase is applied to attractive young men it is now often considered as a compliment. This research sets out to study the feminisation phenomena in the representation of warriors in Chinese language films from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Mainland China made in the first decade of the new millennium (2000-2009), as these three regions are now often packaged together as a pan-unity of the Chinese cultural realm. The foci of this study are on the investigations of the warriors as the feminised Other from two aspects: their bodies as spectacles and the manifestation of feminine characteristics in the male warriors. This study aims to detect what lies underneath the beautiful masquerade of the warriors as the Other through comprehensive analyses of the representations of feminised warriors and comparison with their female counterparts. It aims to test the hypothesis that gender identities are inventory categories transformed by and with changing historical context. Simultaneously, it is a project to study how Chinese traditional values and postmodern metrosexual culture interacted to formulate Chinese contemporary masculinity. It is also a project to search for a cultural nationalism presented in these films with the examination of gender politics hidden in these feminisation phenomena. With Laura Mulvey‘s theory of the gaze as a starting point, this research reconsiders the power relationship between the viewing subject and the spectacle to study the possibility of multiple gaze as well as the power of spectacle. -

Mark Twain Circular

12 Mark Twain Circular Newsletter of the Mark Twain Circle of America Volume 29 November 2015 Number 2 that I get paid to think about and talk about President’s Column Mark Twain, something I would do for John Bird nothing (but don’t tell my university). Winthrop University As another year begins to wind to a close, I think about how much of my year has centered around this person who died over a hundred years ago. I spent much of my summer reading all the Twain books and articles from 2014 for the “Mark Twain” chapter in American Literary Scholarship, Inside This Issue then scrambling to Twain Talk: distill all that into 20 Peter Messent pages of summary Fall Feature: and evaluation. Nee Brothers’ New Mark Twain is Indie Film, Band of indeed alive and Robbers well in the academy, Mark Twain Circle: and now it is time to I am teaching a graduate seminar on Mark Annual Minutes turn my attention to Twain this semester, a class I have taught two Member Renewal the scholarly work or three times before. It is always a great Calls for Papers: from 2015. My good experience and a great privilege. Most of my ALA 2016 friend from ten students had read Huckleberry Finn, but MLA 2017 most had not read anything else by Twain graduate school, before the class started. So it is very exciting Gary, stopped by the to share with them and watch them read other day on his way to Florida, and I was works including “A Jumping Frog,” Innocents telling him how envious I was of him back Abroad, Roughing It, Tom Sawyer, Huckleberry then in the early 1980s that he had published Finn, A Connecticut Yankee, Pudd’nhead on Mark Twain and had been included in one Wilson, and No. -

Domestic Blitz: a Revisionist History of the Fifties

Domestic Blitz: A Revisionist History of the Fifties Gaile McGregor The fir st version of this paper was written for a 1990 conference at the University of Kansas entitled "Ikë s America." It was an interesting event—though flawed somewhat by the organizers' decision to schedule sessions and design program flow according to academic category. Eminently sensible from an administrative standpoint, this arrangement worked counter to the articulated aim of stimulating interdisciplinary dialogue by encouraging participants to spend all their time hanging out with birds of their own feather—economists with economists, historians with historians, literati with literati. Like many of the would-be innovative conferences, symposia, andevenfull-scale academic programsmounted over the last decade, this one was multi- rather than truly inter-disciplinary. This didn' t mean that I wasn t able to find any critical grist for my mill. Substantive aspects aside, the two things I found most intriguing about what I heard during those few days were, first, the number and variety of people who had recently "rediscovered" the fifties, and second, the extent to which the pattern of their rediscovery paralleled my own. Arriving there convinced I had made a major breakthrough in elucidating the darker and more complex feelings that undercolored the broadly presumed conservatism of the decade, what I heard over and over again from presenter s was the same (gleeful or earnest) revisions, the same sense of surprise at how much had been overlooked. Two messages might be taken from this. The first is that the fifties is suddenly relevant again. The second and perhaps more sobering concerns the mind-boggling power of 0026-3079/93/3401 -005$ 1.50/0 5 American culture to foster an almost complete collective amnesia about events and attitudes of the not-very-distant past. -

Mark Twain and the Bible

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Kentucky University of Kentucky UKnowledge American Literature American Studies 1969 Mark Twain and the Bible Allison Ensor University of Tennessee - Knoxville Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Ensor, Allison, "Mark Twain and the Bible" (1969). American Literature. 4. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_american_literature/4 Mark Twain & The Bible This page intentionally left blank MARK TWAIN & THE JBIJBLE Allison Ensor UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY PRESS Copyright (c) I 969 UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY PRESS, LEXINGTON Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 76-80092 Standard Book NU11lber 8131-1181-1 TO Anne & Beth This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgments THis BOOK could not have been what it is without the assistance of several persons whose help I gratefully acknowledge: Professor Edwin H. Cady, Indiana Uni versity, guided me through the preliminaries of this study; Professor Nathalia Wright, University of Ten nessee, whose study of Melville and the Bible is still a standard work, read my manuscript and made valuable suggestions; Professor Henry Nash Smith, University of California at Berkeley, former editor of the Mark Twain Papers, read an earlier version of the book and encouraged and directed me by his comments on it; the Graduate School of the University of Tennessee awarded me a summer grant, releasing me from teach ing responsibilities for a term so that I might revise the manuscript; and my wife, Anne Lovell Ensor, was will ing to accept Mark Twain as a member of the family for some five years. -

Apaches and Comanches on Screen Kenneth Estes Hall East Tennessee State University, [email protected]

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University ETSU Faculty Works Faculty Works 1-1-2012 Apaches and Comanches on Screen Kenneth Estes Hall East Tennessee State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etsu-works Part of the American Film Studies Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Citation Information Hall, Kenneth Estes. (true). 2012. Apaches and Comanches on Screen. Studies in the Western. Vol.20 27-41. http://www.westernforschungszentrum.de/ This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in ETSU Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Apaches and Comanches on Screen Copyright Statement This document was published with permission from the journal. It was originally published in the Studies in the Western. This article is available at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University: https://dc.etsu.edu/etsu-works/591 Apaches and Comanches on Screen Kenneth E. Hall A generally accurate appraisal of Western films might claim that In dians as hostiles are grouped into one undifferentiated mass. Popular hostile groups include the Sioux (without much differentiation between tribes or bands, the Apaches, and the Comanches). Today we will examine the images of Apache and Comanche groups as presen ted in several Western films. In some cases, these groups are shown with specific, historically identifiable leaders such as Cochise, Geron imo, or Quanah Parker. -

Timber for the Comstock

In October 2008, the Society of American Foresters will hold its convention in Reno, Nevada. Attendees can visit nearby Virginia City, the home of America’s first major “silver rush,” the Comstock Lode. Virginia City was built over one of North America’s largest silver deposits and a “forest of underground timbers.” Demand for timber was satisfied by the large forest at the upper elevations of the Sierra Nevada, especially around Lake Tahoe. After discussing historical background, this article offers a short forest history tour based on Nevada historical markers and highlighting Lake Tahoe logging history. TIMBER FOR THE COMSTOCK old was discovered in western Nevada around 1850 by prospectors on their way to California. In early 1859, James Finney and a small group of G prospectors discovered the first indications of silver ore near present-day Virginia City. Later that year other prospectors located the ledge of a major gold lode. Fellow prospector Henry Comstock claimed the ledge Over the next twenty years, the 21⁄2-mile deposit of high-grade as being on his property and soon gained an interest in the area, ore would produce nearly $400 million in silver and gold, create and the strike became known as the Comstock Lode. Finney, several fortunes, and lead to Nevada’s early admission to the nicknamed “Old Virginny” after his birthplace, reportedly named Union during the Civil War, even though it lacked the popula- the collection of mining tents in honor of himself during a tion required by the Constitution to become a state.2 In 1873, a drunken celebration. -

Stereotypes of Contemporary Native American Indian Characters in Recent Popular Media Virginia A

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2012 Stereotypes of Contemporary Native American Indian Characters in Recent Popular Media Virginia A. Mclaurin University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, and the Television Commons Mclaurin, Virginia A., "Stereotypes of Contemporary Native American Indian Characters in Recent Popular Media" (2012). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 830. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/830 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Stereotypes of Contemporary Native American Indian Characters in Recent Popular Media A Thesis Presented by Virginia A. McLaurin Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2012 Department of Anthropology Sociocultural Anthropology Stereotypes of Contemporary Native American Indian Characters in Recent Popular Media A Thesis Presented by Virginia A. McLaurin Approved as to style and content by: _________________________________________________ Jean Forward, Chair _________________________________________________ Robert Paynter, Member _________________________________________________ Jane Anderson, Member _________________________________________________ Elizabeth Chilton, Department Chair Anthropology Department DEDICATION To my wonderful fiancé Max, as well as my incredibly supportive parents, friends and entire family. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Jean Forward, not only for her support and guidance but also for kindness and general character. -

Read the Introduction

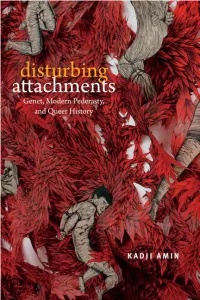

disturbing attachments A series edited by Lauren Berlant and Lee Edelman disturbing attachments Genet, Modern Pederasty, and Queer History KADJI AMIN Duke University Press · Durham and London · 2017 © 2017 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Amy Ruth Buchanan Typeset in Arno Pro by Copperline Books Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data Names: Amin, Kadji, [date– ] author. Title: Disturbing attachments [electronic resource] : Genet, modern pederasty, and queer history / Kadji Amin. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2017. | Series: Theory Q | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Description based on print version record and cip data provided by publisher; resource not viewed. Identifiers: lccn 2017009234 (print) | lccn 2017015463 (ebook) isbn 9780822368892 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822369172 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 9780822372592 (e-book) Subjects: lcsh: Genet, Jean, 1910–1986. | Homosexuality in literature. | Queer theory. Classification: lcc pq2613.e53 (ebook) | lcc pq2613.e53 z539 2017 (print) | ddc 842/.912—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017009234 Cover art: Felipe Baeza, Fogata, 2013. Woodblock, silkscreen, and monoprint on varnished paper. Courtesy of the artist. contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS · ix INTRODUCTION · 1 CHAPTER 1 · 19 Attachment Genealogies of Pederastic Modernity CHAPTER 2 · 45 Light of a Dead Star: The Nostalgic Modernity of Prison Pederasty CHAPTER 3 · 76 Racial Fetishism, Gay Liberation, and the Temporalities of the Erotic CHAPTER 4 · 109 Pederastic Kinship CHAPTER 5 · 141 Enemies of the State: Terrorism, Violence, and the Affective Politics of Transnational Coalition EPILOGUE · 176 Haunted by the 1990s: Queer Theory’s Affective Histories NOTES · 191 BIBLIOGRAPHY · 235 INDEX · 249 Solange: S’aimer dans le dégoût, ce n’est pas s’aimer.