Lang V. Kohl's Food Stores, Inc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FY 2020 Announcement.Pdf

17 February 2021 –PRELIMINARY RESULTS BRITISH AMERICAN TOBACCO p.l.c. YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2020 ‘ACCELERATING TRANSFORMATION’ GROWTH IN NEW CATEGORIES AND GROUP EARNINGS DESPITE COVID-19 PERFORMANCE HIGHLIGHTS REPORTED ADJUSTED Current Vs 2019 Current Vs 2019 rates Rates (constant) Cigarette and THP volume share +30 bps Cigarette and THP value share +20 bps Non-Combustibles consumers1 13.5m +3.0m Revenue (£m) £25,776m -0.4% £25,776m +3.3% Profit from operations (£m) £9,962m +10.5% £11,365m +4.8% Operating margin (%) +38.6% +380 bps +44.1% +100 bps2 Diluted EPS (pence) 278.9p +12.0% 331.7p +5.5% Net cash generated from operating activities (£m) £9,786m +8.8% Free cash flow after dividends (£m) £2,550m +32.7% Cash conversion (%)2 98.2% -160 bps 103.0% +650 bps Borrowings3 (£m) £43,968m -3.1% Adjusted Net Debt (£m) £39,451m -5.3% Dividend per share (pence) 215.6p +2.5% The use of non-GAAP measures, including adjusting items and constant currencies, are further discussed on pages 48 to 53, with reconciliations from the most comparable IFRS measure provided. Note – 1. Internal estimate. 2. Movement in adjusted operating margin and operating cash conversion are provided at current rates. 3. Borrowings includes lease liabilities. Delivering today Building A Better TomorrowTM • Revenue, profit from operations and earnings • 1 growth* absorbing estimated 2.5% COVID-19 revenue 13.5m consumers of our non-combustible products , headwind adding 3m in 2020. On track to 50m by 2030 • New Categories revenue up 15%*, accelerating • Combustible revenue -

Brands MSA Manufacturers Dateadded 1839 Blue 100'S Box

Brands MSA Manufacturers DateAdded 1839 Blue 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Blue King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Menthol Blue 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Menthol Blue King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Menthol Green 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Menthol Green King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Non Filter King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Red 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Red King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 RYO 16oz Blue Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 RYO 16oz Full Flavor Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 RYO 16oz Menthol Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 RYO 6 oz Full Flavor Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 RYO 6oz Blue Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 RYO 6oz Menthol Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Silver 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Silver King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Blue 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Blue King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Menthol Green 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Menthol Green King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Menthol Silver 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Non Filter King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Red 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Red King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Silver 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 24/7 Gold 100's Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 24/7 Gold King Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 24/7 Menthol 100's Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 24/7 Menthol Gold 100's Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 24/7 Menthol King Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 24/7 Red 100's Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 24/7 Red King Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 24/7 Silver Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 Amsterdam Shag 35g Pouch or 150g Tin Peter Stokkebye Tobaksfabrik A/S 7/1/2021 Bali Shag RYO gold or navy pouch or canister Top Tobacco L.P. -

Group Income Statement

news release www.bat.com 06 May 2009 BRITISH AMERICAN TOBACCO p.l.c. INTERIM MANAGEMENT STATEMENT FOR THE THREE MONTHS ENDED 31 MARCH 2009 • Strong revenue growth at both constant and current exchange rates • Volumes from subsidiaries increased 7 per cent to 170 billion • All four Global Drive Brands grew volume, with overall growth of 7 per cent Trading update British American Tobacco had a good start to 2009 and is continuing to build on the success achieved in 2008. Group revenue for the three months grew strongly in constant currency terms, driven by the continued good pricing momentum and volume growth from the acquisitions made in the middle of last year (Skandinavisk Tobakskompagni (ST) and Tekel). All regions contributed to this good result. Revenue benefited further from the favourable impact of significant exchange rate movements which more than offset the adverse transactional impact of exchange rates on costs. Group volumes from subsidiaries were 170 billion, up 7 per cent, mainly as a result of the acquisitions of ST and Tekel. Excluding the benefits of these acquisitions, volumes were in line with last year with premium volumes slightly ahead. The four Global Drive Brands continued their strong performance and achieved overall volume growth of 7 per cent. Dunhill was up 8 per cent, Kent 3 per cent, Lucky Strike 4 per cent and Pall Mall grew by 11 per cent. Cigarette volumes The segmental analysis of the volumes of subsidiaries is as follows: 3 months to Year to 31.03.09 31.03.08 31.12.08 bns bns bns Asia-Pacific 43.3 42.9 179.5 Americas 37.9 39.2 161.0 Western Europe 29.7 25.1 122.6 Eastern Europe 27.1 29.1 137.3 Africa and Middle East 31.5 22.1 114.2 169.5 158.4 714.6 Trading environment This performance was achieved against general trading conditions which became tougher during the quarter with lower industry volumes in a number of key markets and a deceleration of growth in the premium segment. -

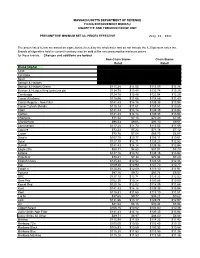

Cigarette Minimum Retail Price List

MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE FILING ENFORCEMENT BUREAU CIGARETTE AND TOBACCO EXCISE UNIT PRESUMPTIVE MINIMUM RETAIL PRICES EFFECTIVE July 26, 2021 The prices listed below are based on cigarettes delivered by the wholesaler and do not include the 6.25 percent sales tax. Brands of cigarettes held in current inventory may be sold at the new presumptive minimum prices for those brands. Changes and additions are bolded. Non-Chain Stores Chain Stores Retail Retail Brand (Alpha) Carton Pack Carton Pack 1839 $86.64 $8.66 $85.38 $8.54 1st Class $71.49 $7.15 $70.44 $7.04 Basic $122.21 $12.22 $120.41 $12.04 Benson & Hedges $136.55 $13.66 $134.54 $13.45 Benson & Hedges Green $115.28 $11.53 $113.59 $11.36 Benson & Hedges King (princess pk) $134.75 $13.48 $132.78 $13.28 Cambridge $124.78 $12.48 $122.94 $12.29 Camel All others $116.56 $11.66 $114.85 $11.49 Camel Regular - Non Filter $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Camel Turkish Blends $110.14 $11.01 $108.51 $10.85 Capri $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Carlton $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Checkers $71.54 $7.15 $70.49 $7.05 Chesterfield $96.53 $9.65 $95.10 $9.51 Commander $117.28 $11.73 $115.55 $11.56 Couture $72.23 $7.22 $71.16 $7.12 Crown $70.76 $7.08 $69.73 $6.97 Dave's $107.70 $10.77 $106.11 $10.61 Doral $127.10 $12.71 $125.23 $12.52 Dunhill $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Eagle 20's $88.31 $8.83 $87.01 $8.70 Eclipse $137.16 $13.72 $135.15 $13.52 Edgefield $73.41 $7.34 $72.34 $7.23 English Ovals $125.44 $12.54 $123.59 $12.36 Eve $109.30 $10.93 $107.70 $10.77 Export A $120.88 $12.09 $119.10 $11.91 -

Manufacturer Brand Style Length (Mm's) Circ

Iowa Approved Fire Standard Compliant Cigarettes -04/01/2021 (SORTED BY BRAND STYLE) Date Length Circ Certified/ Manufacturer Brand Style (mm's) (mm's) Flavor Filter Package Test Date Recertified Premier Manufacturing, Inc. 1839 Blue 100 Box 97.90 24.60 Regular Filter Box 03/30/18 01/11/21 Premier Manufacturing, Inc. 1839 Blue King Box 82.40 24.60 Regular Filter Box 04/03/18 01/11/21 Premier Manufacturing, Inc. 1839 Menthol Blue 100 Box 97.90 24.70 Menthol Filter Box 03/30/18 01/11/21 Premier Manufacturing, Inc. 1839 Menthol Blue King Box 82.90 24.60 Menthol Filter Box 04/04/18 01/11/21 Premier Manufacturing, Inc. 1839 Menthol Green 100 Box 97.30 24.60 Menthol Filter Box 04/02/18 01/11/21 Premier Manufacturing, Inc. 1839 Menthol Green King Box 83.00 24.50 Menthol Filter Box 04/04/18 01/11/21 Premier Manufacturing, Inc. 1839 Red 100 Box 97.80 24.60 Regular Filter Box 03/30/18 01/11/21 Premier Manufacturing, Inc. 1839 Red King Box 82.80 24.70 Regular Filter Box 04/03/18 01/11/21 Premier Manufacturing, Inc. 1839 Silver 100 Box 97.40 24.70 Regular Filter Box 04/03/18 01/11/21 Premier Manufacturing, Inc. 1839 Silver King Box 82.80 24.70 Regular Filter Box 04/04/18 01/11/21 Premier Manufacturing, Inc. 1st Class Blue 100's Box 97.10 24.60 Regular Filter Box 04/05/18 01/11/21 Premier Manufacturing, Inc. 1st Class Blue Kings Box 82.80 24.70 Regular Filter Box 04/05/18 01/11/21 Premier Manufacturing, Inc. -

Cigarettes by Manufacturer

North Dakota Office of Attorney General Fire Marshal Division Certified Cigarettes by Manufacturer Manufacturer Brand Description Renewal British American Tobacco Singapore State Express 555 Gold Filter Box 06/21/2022 British American Tobacco Switzerland Dunhill Black Fine Cut Filter Box 06/21/2022 Dunhill Blue International Filter Box 06/21/2022 Dunhill Green International Menthol Filter Box 06/21/2022 Dunhill Red International Filter Box 06/21/2022 Dunhill White Fine Cut Filter Box 06/21/2022 Cheyenne International, LLC Aura Glen Menthol Filter Box 07/15/2022 Aura Radiant Gold Filter Box 07/15/2022 Aura Robust Red Filter Box 07/15/2022 Aura Sky Blue Filter Box 07/15/2022 Cheyenne 100's Menthol Filter Box 07/15/2022 Cheyenne Gold 100's Filter Box 07/15/2022 Cheyenne Gold Kings Filter Box 07/15/2022 Cheyenne Kings Non-Filter Box 07/15/2022 Cheyenne Kings Menthol Filter Box 07/15/2022 Cheyenne Red 100's Filter Box 07/15/2022 Cheyenne Red Kings Filter Box 07/15/2022 Cheyenne Silver 100's Filter Box 07/15/2022 Cheyenne Silver 100's Menthol Filter Box 07/15/2022 Cheyenne Silver Kings Menthol Filter Box 07/15/2022 Cheyenne Silver Kings Filter Box 07/15/2022 Decade 100's Menthol Filter Box 07/15/2022 Decade Gold 100's Filter Box 07/15/2022 Decade Gold Kings Filter Box 07/15/2022 Decade Kings Menthol Filter Box 07/15/2022 Decade Red 100's Filter Box 07/15/2022 Decade Red Kings Filter Box 07/15/2022 Decade Silver 100"s Filter Box 07/15/2022 Decade Silver 100's Menthol Filter Box 07/15/2022 Decade Silver Kings Menthol Filter Box 07/15/2022 Decade Silver Kings Filter Box 07/15/2022 Commonwealth Brands, Inc. -

Case Study Industry: Tobacco

CASE STUDY INDUSTRY: TOBACCO CUSTOMER: R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company LOCATION: Winston Salem, North Carolina BACKGROUND: R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company is the second-largest tobacco company in the United States, offering products in all segments of the market and makes many of the nation’s best-selling cigarette brands, including: Camel, Pall Mall, Kool, Winston, Salem, Doral, and VUSE brand E-cigarette. SCOPE OF WORK: Armstrong International is responsible for the operation and maintenance of the utilities systems at the Tobaccoville and Whitaker Park Boiler and Process Services plants including all associated equipment to provide quality steam, condensate, chill water, compressed air, and water treatment to meet ISO, FDA, and process requirements of the R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company manufacturing facilities. Armstrong provides one site manager, two operation and maintenance managers as well as 35 operation and maintenance support employees, which includes 18 utility plant operators, one water treatment specialist, four operations and maintenance lead technicians, 11 HVAC and instrumentation technicians, and four mechanical maintenance technicians to furnish continuous plant staffing. BENEFITS: R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company now has on-site utility expertise motivated to continually reduce cost and focus on utility system reliability at two separate manufacturing locations. They also have access to all of Armstrong’s extensive utility/energy engineering resources including the following: • Annual engineering audits • Identification/development -

NVWA Nr. Merk/Type Nicotine (Mg/Sig) NFDPM (Teer)

NVWA nr. Merk/type Nicotine (mg/sig) NFDPM (teer) (mg/sig) CO (mg/sig) 89537347 Lexington 1,06 12,1 7,6 89398436 Camel Original 0,92 11,7 8,9 89398339 Lucky Strike Original Red 0,88 11,4 11,6 89398223 JPS Red 0,87 11,1 10,9 89399459 Bastos Filter 1,04 10,9 10,1 89399483 Belinda Super Kings 0,86 10,8 11,8 89398347 Mantano 0,83 10,8 7,3 89398274 Gauloises Brunes 0,74 10,7 10,1 89398967 Winston Classic 0,94 10,6 11,4 89399394 Titaan Red 0,75 10,5 11,1 89399572 Gauloises 0,88 10,5 10,6 89399408 Elixyr Groen 0,85 10,4 10,9 89398266 Gauloises Blondes Blue 0,77 10,4 9,8 89398886 Lucky Strike Red Additive Free 0,85 10,3 10,4 89537266 Dunhill International 0,94 10,3 9,9 89398932 Superkings Original Black 0,92 10,1 10,1 89537231 Mark 1 New Red 0,78 10 11,2 89399467 Benson & Hedges Gold 0,9 10 10,9 89398118 Peter Stuyvesant Red 0,82 10 10,9 89398428 L & M Red Label 0,78 10 10,5 89398959 Lambert & Butler Original Silver 0,91 10 10,3 89399645 Gladstone Classic 0,77 10 10,3 89398851 Lucky Strike Ice Gold 0,75 9,9 11,5 89537223 Mark 1 Green 0,68 9,8 11,2 89393671 Pall Mall Red 0,84 9,8 10,8 89399653 Chesterfield Red 0,75 9,8 10 89398371 Lucky strike Gold 0,76 9,7 11,1 89399599 Marlboro Gold 0,78 9,6 10,3 89398193 Davidoff Classic 0,88 9,6 10,1 89399637 Marlboro Red 100 0,79 9,6 9 89398878 Lucky Strike Ice 0,71 9,5 10,9 89398045 Pall Mall Red 0,81 9,5 10,5 89398355 Dunhill Master Blend Red 0,82 9,5 9,8 89399475 JPS Red 0,81 9,5 9,6 89398029 Marlboro Red 0,79 9,5 9 89537355 Elixyr Red 0,79 9,4 9,8 89398037 Marlboro Menthol 0,72 9,3 10,3 89399505 Marlboro -

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 4/29/10

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 4/29/10 Beginning August 1, 2008, only the cigarette brands and styles listed below are allowed to be imported, stamped and/or sold in the State of Alaska. Per AS 18.74, these brands must be marked as fire safe on the packaging. The brand styles listed below have been certified as fire safe by the State Fire Marshall, bear the "FSC" marking. There is an exception to these requirements. The new fire safe law allows for the sale of cigarettes that are not fire safe and do not have the "FSC" marking as long as they were stamped and in the State of Alaska before August 1, 2008 and found on the "Directory of MSA Compliant Cigarette & RYO Brands." Filter/ Non- Brand Style Length Circ. Filter Pkg. Descr. Manufacturer 1839 Full Flavor 82.7 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 97 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 83 24.60 Non-Filter Soft Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 83 24.40 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol 83 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol Light 83 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. -

Page 1 of 15

Updated September14, 2021– 9:00 p.m. Date of Next Known Updates/Changes: *Please print this page for your own records* If there are any questions regarding pricing of brands or brands not listed, contact Heather Lynch at (317) 691-4826 or [email protected]. EMAIL is preferred. For a list of licensed wholesalers to purchase cigarettes and other tobacco products from - click here. For information on which brands can be legally sold in Indiana and those that are, or are about to be delisted - click here. *** PLEASE sign up for GovDelivery with your EMAIL and subscribe to “Tobacco Industry” (as well as any other topic you are interested in) Future lists will be pushed to you every time it is updated. *** https://public.govdelivery.com/accounts/INATC/subscriber/new RECENTLY Changed / Updated: 09/14/2021- Changes to LD Club and Tobaccoville 09/07/2021- Update to some ITG list prices and buydowns; Correction to Pall Mall buydown 09/02/2021- Change to Nasco SF pricing 08/30/2021- Changes to all Marlboro and some RJ pricing 08/18/2021- Change to Marlboro Temp. Buydown pricing 08/17/2021- PM List Price Increase and Temp buydown on all Marlboro 01/26/2021- PLEASE SUBSCRIBE TO GOVDELIVERY EMAIL LIST TO RECEIVE UPDATED PRICING SHEET 6/26/2020- ***RETAILER UNDER 21 TOBACCO***(EFF. JULY 1) (on last page after delisting) Minimum Minimum Date of Wholesale Wholesale Cigarette Retail Retail Brand List Manufacturer Website Price NOT Price Brand Price Per Price Per Update Delivered Delivered Carton Pack Premier Mfg. / U.S. 1839 Flare-Cured Tobacco 7/15/2021 $42.76 $4.28 $44.00 $44.21 Growers Premier Mfg. -

First-Of-Its-Kind Filing for VUSE Products

Reynolds American Inc. P.O. Box 2990 Winston-Salem, NC 27102-2990 Media Contact: Kaelan Hollon [email protected] 202-421-4921 VUSE Premarket Tobacco Product Application Filed for Substantive Review by the FDA First-of-its-Kind Filing for VUSE Products WINSTON-SALEM, N.C. – Nov. 27, 2019 – Today, Reynolds American Inc. (“RAI”) announced that the recently-submitted Premarket Tobacco Product Application (“PMTA”) for VUSE vapor products has been filed by the Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”) for substantive scientific review, moving the application one step further through the review process. “This is a first-of-its-kind application for VUSE products, and it puts VUSE one step closer to gaining a marketing order from the FDA. FDA will now review our scientific justification and determine the appropriateness of VUSE e-cigarette products against the public health standard,” notes RAI CEO Ricardo Oberlander. “For adult tobacco consumers seeking an alternative source of nicotine, having FDA oversight of e-cigarette products is an important step to ensure those alternatives meet strict regulatory scrutiny.” The FDA’s scientific review of the VUSE application – which totals more than 150,000 pages of research and data – comes just over six weeks after its initial submission to the FDA. The FDA, per its earlier-issued guidance, considers the following issues, among others: • Risks and benefits to the population as a whole, including both users and nonusers of tobacco products; • Whether people who currently use any tobacco product would be more or less likely to stop using such products if the proposed new tobacco product were available; • Whether people who currently do not use any tobacco products would be more or less likely to begin using tobacco products if the new product were available; and • The methods, facilities, and controls used to manufacture, process, and pack the new tobacco product. -

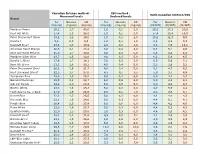

TNCO Levels and Ratio's

Canadian Intense method - ISO method - Ratio Canadian Intense/ISO Measured levels Declared levels Brand Tar Nicotine CO Tar Nicotine CO Tar Nicotine CO (mg/cig) (mg/cig) (mg/cig) (mg/cig) (mg/cig) (mg/cig) (CI/ISO) (CI/ISO) (CI/ISO) Marlboro Prime 26,1 1,7 40,0 1,0 0,1 2,0 26,1 17,2 20,0 Kent HD White 17,4 1,3 28,0 1,0 0,1 2,0 17,4 13,4 14,0 Peter Stuyvesant Silver 15,2 1,2 19,0 1,0 0,1 2,0 15,2 12,3 9,5 Karelia I 9,6 0,9 9,3 1,0 0,1 1,0 9,6 8,6 9,3 Davidoff Blue* 23,6 1,7 30,9 2,9 0,2 2,6 8,3 7,0 12,1 American Spirit Orange 20,5 2,1 18,4 3,0 0,4 4,0 6,8 5,1 4,6 Kent Surround Menthol 25,0 1,7 30,8 4,0 0,4 5,0 6,3 4,3 6,2 Marlboro Silver Blue 24,7 1,5 32,6 4,0 0,3 5,0 6,2 5,0 6,5 Karelia L (Blue) 17,6 1,7 14,1 3,0 0,3 2,0 5,9 5,6 7,1 Kent HD Silver 21,1 1,6 26,2 4,0 0,4 5,0 5,3 3,9 5,2 Peter Stuyvesant Blue* 20,2 1,6 21,7 4,0 0,4 5,0 5,1 4,7 4,3 Kent Surround Silver* 22,5 1,7 27,0 4,5 0,5 5,5 5,0 3,7 4,9 Templeton Blue 25,0 1,8 26,2 5,0 0,4 6,0 5,0 4,4 4,4 Belinda Filterkings 29,9 2,2 24,7 6,0 0,5 6,0 5,0 4,3 4,1 Silk Cut Purple 24,9 2,0 23,4 5,0 0,5 5,0 5,0 4,0 4,7 Boston White 23,3 1,6 25,3 5,0 0,3 6,0 4,7 5,5 4,2 Mark Adams No.