Looking for Science and Mathematics in All the Right Places: Using Mobile Technologies As Culturally-Sensitive Pedagogical Tools to Capture Generative Images

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WEB KARAOKE EN-NL.Xlsx

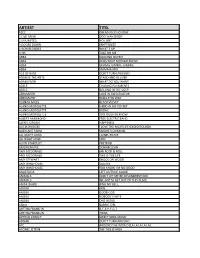

ARTIEST TITEL 10CC DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 2 LIVE CREW DOO WAH DIDDY 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE 4 NON BLONDES WHAT´S UP A HA TAKE ON ME ABBA DANCING QUEEN ABBA DOES YOUR MOTHER KNOW ABBA GIMMIE GIMMIE GIMMIE ABBA MAMMA MIA ACE OF BASE DON´T TURN AROUND ADAM & THE ANTS STAND AND DELIVER ADAM FAITH WHAT DO YOU WANT ADELE CHASING PAVEMENTS ADELE ROLLING IN THE DEEP AEROSMITH LOVE IN AN ELEVATOR AEROSMITH WALK THIS WAY ALANAH MILES BLACK VELVET ALANIS MORISSETTE HAND IN MY POCKET ALANIS MORISSETTE IRONIC ALANIS MORISSETTE YOU OUGHTA KNOW ALBERT HAMMOND FREE ELECTRIC BAND ALEXIS JORDAN HAPPINESS ALICIA BRIDGES I LOVE THE NIGHTLIFE (DISCO ROUND) ALIEN ANT FARM SMOOTH CRIMINAL ALL NIGHT LONG LIONEL RICHIE ALL RIGHT NOW FREE ALVIN STARDUST PRETEND AMERICAN PIE DON MCLEAN AMY MCDONALD MR ROCK & ROLL AMY MCDONALD THIS IS THE LIFE AMY STEWART KNOCK ON WOOD AMY WINEHOUSE VALERIE AMY WINEHOUSE YOU KNOW I´M NO GOOD ANASTACIA LEFT OUTSIDE ALONE ANIMALS DON´T LET ME BE MISUNDERSTOOD ANIMALS WE GOTTA GET OUT OF THIS PLACE ANITA WARD RING MY BELL ANOUK GIRL ANOUK GOOD GOD ANOUK NOBODY´S WIFE ANOUK ONE WORD AQUA BARBIE GIRL ARETHA FRANKLIN R-E-S-P-E-C-T ARETHA FRANKLIN THINK ARTHUR CONLEY SWEET SOUL MUSIC ASWAD DON´T TURN AROUND ATC AROUND THE WORLD (LA LA LA LA LA) ATOMIC KITTEN THE TIDE IS HIGH ARTIEST TITEL ATOMIC KITTEN WHOLE AGAIN AVRIL LAVIGNE COMPLICATED AVRIL LAVIGNE SK8TER BOY B B KING & ERIC CLAPTON RIDING WITH THE KING B-52´S LOVE SHACK BACCARA YES SIR I CAN BOOGIE BACHMAN TURNER OVERDRIVE YOU AIN´T SEEN NOTHING YET BACKSTREET BOYS -

A Silver of Hope Up-And-Comers Top Jerome

SATURDAY, APRIL 23, 2011 For information about TDN, call 732-747-8060. A SILVER OF HOPE KEENELAND TO LAUNCH ADW On the outside looking in at the moment, the (Edited press release) The Keeneland Association connections of Silver Medallion (Badge of Silver) will announced today that it plans to launch an advanced make a last attempt at getting into the field for the deposit wagering system this fall. The ADW platform, May 7 GI Kentucky Derby by which will be powered by TwinSpires.com, will allow sending their sophomore to the horse players to wager on Keeneland racing in the gate for today=s GIII Coolmore spring and fall, as well as throughout the year on other Lexington S. at Keeneland. The tracks. AAfter much thought and deliberation, we bay made his dirt debut as the elected to move forward with launching our own ADW, 5-2 favorite in the Apr. 9 because we are committed to catering to our fans and GI Santa Anita Derby, but faded providing them the services they want in a way that is late to be fourth. Currently 24th convenient for them,@ said Keeneland President and Horsephotos on the list with $184,334 in CEO Nick Nicholson. AIn addition, it will allow us to graded earnings, he will likely boost our purses and reinvest in our industry.@ Unique need every penny of the $120,000 winner=s share of in structure, the Keeneland Association invests its the Lexington purse if he is to be assured of cracking proceeds back into its racing program, the the top 20 for the ARun for the Roses.@ The Black Rock Thoroughbred industry and the community. -

Human Computing and Crowdsourcing Methods for Knowledge Acquisition

UNIVERSITÄT DES SAARLANDES DOCTORAL THESIS Human Computing and Crowdsourcing Methods for Knowledge Acquisition Sarath Kumar Kondreddi Max Planck Institut für Informatik A dissertation presented for the degree of Doctor of Engineering in the Faculty of Natural Sciences and Technology UNIVERSITY OF SAARLAND Saarbrücken, May 2014 PROMOTIONSKOLLOQUIUM Datum 06 Mai 2014 Ort Saarbrücken Dekan der Naturwissenschaftlich- Prof. Dr-Ing. Markus Bläser Technischen Fakultät I Universität des Saarlandes PRÜFUNGSKOMMISSION Vorsitzender Prof. Matthias Hein Gutachter Prof. Dr.-Ing. Gerhard Weikum Gutachter Prof. Peter Triantafillou Gutachter Dr.-Ing. Klaus Berberich Beisitzer Dr.-Ing. Sebastian Michel UNIVERSITÄT DES SAARLANDES Thesis Abstract Database and Information Systems Group Max-Planck Institute for Informatics Doctor of Engineering Human Computing and Crowdsourcing Methods for Knowledge Acquisition by Sarath Kumar KONDREDDI ABSTRACT Ambiguity, complexity, and diversity in natural language textual expressions are major hindrances to automated knowledge extraction. As a result state-of-the-art methods for extracting entities and relationships from unstructured data make in- correct extractions or produce noise. With the advent of human computing, com- putationally hard tasks have been addressed through human inputs. While text- based knowledge acquisition can benefit from this approach, humans alone cannot bear the burden of extracting knowledge from the vast textual resources that exist today. Even making payments for crowdsourced acquisition can quickly become prohibitively expensive. In this thesis we present principled methods that effectively garner human com- puting inputs for improving the extraction of knowledge-base facts from natural language texts. Our methods complement automatic extraction techniques with hu- man computing to reap benefits of both while overcoming each other’s limitations. -

Track 1 Juke Box Jury

CD1: 1959-1965 CD4: 1971-1977 Track 1 Juke Box Jury Tracks 1-6 Mary, Queen Of Scots Track 2 Beat Girl Track 7 The Persuaders Track 3 Never Let Go Track 8 They Might Be Giants Track 4 Beat for Beatniks Track 9 Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland Track 5 The Girl With The Sun In Her Hair Tracks 10-11 The Man With The Golden Gun Track 6 Dr. No Track 12 The Dove Track 7 From Russia With Love Track 13 The Tamarind Seed Tracks 8-9 Goldfinger Track 14 Love Among The Ruins Tracks 10-17 Zulu Tracks 15-19 Robin And Marian Track 18 Séance On A Wet Afternoon Track 20 King Kong Tracks 19-20 Thunderball Track 21 Eleanor And Franklin Track 21 The Ipcress File Track 22 The Deep Track 22 The Knack... And How To Get It CD5: 1978-1983 CD2: 1965-1969 Track 1 The Betsy Track 1 King Rat Tracks 2-3 Moonraker Track 2 Mister Moses Track 4 The Black Hole Track 3 Born Free Track 5 Hanover Street Track 4 The Wrong Box Track 6 The Corn Is Green Track 5 The Chase Tracks 7-12 Raise The Titanic Track 6 The Quiller Memorandum Track 13 Somewhere In Time Track 7-8 You Only Live Twice Track 14 Body Heat Tracks 9-14 The Lion In Winter Track 15 Frances Track 15 Deadfall Track 16 Hammett Tracks 16-17 On Her Majesty’s Secret Service Tracks 17-18 Octopussy CD3: 1969-1971 CD6: 1983-2001 Track 1 Midnight Cowboy Track 1 High Road To China Track 2 The Appointment Track 2 The Cotton Club Tracks 3-9 The Last Valley Track 3 Until September Track 10 Monte Walsh Track 4 A View To A Kill Tracks 11-12 Diamonds Are Forever Track 5 Out Of Africa Tracks 13-21 Walkabout Track 6 My Sister’s Keeper -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

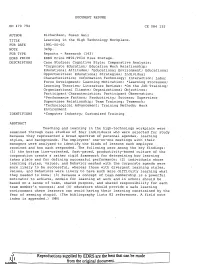

Learning in the High Technology Workplace. PUB DATE 1991-00-00 NOTE 349P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 470 794 CE 084 152 AUTHOR Richardson, Susan Gail TITLE Learning in the High Technology Workplace. PUB DATE 1991-00-00 NOTE 349p. PUB TYPE Reports Research (143) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC14 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Case Studies; Cognitive Style; Comparative Analysis; *Corporate Education; Education Work Relationship; Educational Attitudes; *Educational Environment; Educational Opportunities; Educational Strategies; Individual Characteristics; Information Technology; Interaction; Labor Force Development; Learning Motivation; *Learning Processes; Learning Theories; Literature Reviews; *On the Job Training; Organizational Climate; Organizational Objectives; Participant Characteristics; Participant Observation; *Performance Factors; Productivity; Success; Supervisor Supervisee Relationship; Team Training; Teamwork; *Technological Advancement; Training Methods; Work Environment IDENTIFIERS *Computer Industry; Customized Training ABSTRACT Teaching and learning in the high-technology workplace were examined through case studies of four individuals who were selected for study because they represented a broad spectrum of personal agendas, learning styles, and backgrounds. The employees' one-on-one meetings with their managers were analyzed to identify the kinds of lessons each employee received and how each responded. The following were among the key findings: (1) the bottom line-oriented, fast-paced, productivity-based culture of the corporation create a rather rigid framework for determining how learning takes place and -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

Mikky Ekko Has Come Home. He Recorded His 2015 Debut Album

Mikky Ekko has come home. He recorded his 2015 debut album, Time, in places as far-flung as London, Stockholm, and Los Angeles, plus any point on the compass where inspiration struck while he was on tour with Justin Timberlake, One Republic and Jessie Ware. But he wanted to record Fame, his next album, in the city that had proved both a permanent address and an inspiration for him since moving there in 2005 to attend college. It’s said that people have lucky cities, a geographic location where they seem to flourish or feel that they are their best selves. Although born in Shreveport, Louisiana, with its rich history of country rock and electric blues, Ekko found such a place in Nashville. It allowed him the freedom to be who he wanted to be — starting with those early gigs he played at 12th and Porter with slashes of red painted across his chiseled face. It informed the haunting music of his largely a cappella 2009 dreamscape Strange Fruit, a five-song EP he recorded while still a student at nearby Middle Tennessee State University that had far more in common with Brian Eno than it did Billie Holiday. A restless creator — sometimes writing two songs a day, starting most days at 4:45 am — Ekko quickly followed up Strange Fruit with two companion EPs the next year: Reds and Blues. One of the songs on Reds, "Who Are You, Really,” made its way to underground beatsmith Clams Casino, known mainly for his work with ASAP Rocky, Lil B and The Weeknd. -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1990S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1990s Page 174 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1990 A Little Time Fantasy I Can’t Stand It The Beautiful South Black Box Twenty4Seven featuring Captain Hollywood All I Wanna Do is Fascinating Rhythm Make Love To You Bass-O-Matic I Don’t Know Anybody Else Heart Black Box Fog On The Tyne (Revisited) All Together Now Gazza & Lindisfarne I Still Haven’t Found The Farm What I’m Looking For Four Bacharach The Chimes Better The Devil And David Songs (EP) You Know Deacon Blue I Wish It Would Rain Down Kylie Minogue Phil Collins Get A Life Birdhouse In Your Soul Soul II Soul I’ll Be Loving You (Forever) They Might Be Giants New Kids On The Block Get Up (Before Black Velvet The Night Is Over) I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight Alannah Myles Technotronic featuring Robert Palmer & UB40 Ya Kid K Blue Savannah I’m Free Erasure Ghetto Heaven Soup Dragons The Family Stand featuring Junior Reid Blue Velvet Bobby Vinton Got To Get I’m Your Baby Tonight Rob ‘N’ Raz featuring Leila K Whitney Houston Close To You Maxi Priest Got To Have Your Love I’ve Been Thinking Mantronix featuring About You Could Have Told You So Wondress Londonbeat Halo James Groove Is In The Heart / Ice Ice Baby Cover Girl What Is Love Vanilla Ice New Kids On The Block Deee-Lite Infinity (1990’s Time Dirty Cash Groovy Train For The Guru) The Adventures Of Stevie V The Farm Guru Josh Do They Know Hangin’ Tough It Must Have Been Love It’s Christmas? New Kids On The Block Roxette Band Aid II Hanky Panky Itsy Bitsy Teeny Doin’ The Do Madonna Weeny Yellow Polka Betty Boo -

What Is Test-Driven Development?

www.allitebooks.com Test-Driven Development with Django Develop powerful, fully-featured Django applications by writing tests first Kevin Harvey BIRMINGHAM - MUMBAI www.allitebooks.com Test-Driven Development with Django Copyright © 2015 Packt Publishing All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles or reviews. Every effort has been made in the preparation of this book to ensure the accuracy of the information presented. However, the information contained in this book is sold without warranty, either express or implied. Neither the author, nor Packt Publishing, and its dealers and distributors will be held liable for any damages caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by this book. Packt Publishing has endeavored to provide trademark information about all of the companies and products mentioned in this book by the appropriate use of capitals. However, Packt Publishing cannot guarantee the accuracy of this information. First published: July 2015 Production reference: 1230715 Published by Packt Publishing Ltd. Livery Place 35 Livery Street Birmingham B3 2PB, UK. ISBN 978-1-78528-116-7 www.packtpub.com www.allitebooks.com Credits Author Copy Editor Kevin Harvey Yesha Gangani Reviewers Project Coordinator Ian Cordasco Milton Dsouza Anamta Farook Jason Myers Proofreader Safis Editing Vimal Atreya Ramaka Yogendra Sharma Indexer Rekha Nair Commissioning Editor Ashwin Nair Production Coordinator Melwyn D'sa Acquisition Editor Shaon Basu Cover Work Melwyn D'sa Content Development Editor Susmita Sabat Technical Editors Prajakta Mhatre Manan Patel www.allitebooks.com About the Author Kevin Harvey first fell in love with Django while living in Quelimane, Mozambique, in 2007. -

Aretha Franklin Looking out on the Morning Rain I Used to Feel So

A1: Natural Woman – Aretha Franklin Looking out on the morning rain I used to feel so uninspired And when I knew I had to face another day Lord, it made me feel so tired Before the day I met you, life was so unkind But your the key to my peace of mind 'Cause you make me feel You make me feel You make me feel like A natural woman (woman) When my soul was in the lost and found You came along to claim it I didn't know just what was wrong with me Till your kiss helped me name it Now I'm no longer doubtful, of what I'm living for And if I make you happy I don't need to do more 'Cause you make me feel You make me feel You make me feel like A natural woman (woman) Oh, baby, what you've done to me (what you've done to me) You make me feel so good inside (good inside) And I just want to be, close to you (want to be) You make me feel so alive You make me feel You make me feel You make me feel like A natural woman (woman) (repeat to close) A2: Across the Universe - Beatles Words are flowing out like endless rain into a paper cup, They slither while they pass, they slip away across the universe Pools of sorrow, waves of joy are drifting through my open mind, Possessing and caressing me. Jai guru deva om Nothing's gonna change my world, Nothing's gonna change my world. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun