Sd-Sample Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Region VII 16,336,491,000 936 Projects

Annual Infrastructure Program Revisions Flag: (D)elisted; (M)odified; (R)ealigned; (T)erminated Operating Unit/ Revisions UACS PAP Project Component Decsription Project Component ID Type of Work Target Unit Target Allocation Implementing Office Flag Region VII 16,336,491,000 936 projects GAA 2016 MFO-1 7,959,170,000 202 projects Bohol 1st District Engineering Office 1,498,045,000 69 projects BOHOL (FIRST DISTRICT) Network Development - Off-Carriageway Improvement including drainage 165003015600115 Tagbilaran East Rd (Tagbilaran-Jagna) - K0248+000 - K0248+412, P00003472VS-CW1 Off-Carriageway Square meters 6,609 62,000,000 Region VII / Region VII K0248+950 - K0249+696, K0253+000 - K0253+215, K0253+880 - Improvement: Shoulder K0254+701 - Off-Carriageway Improvement: Shoulder Paving / Paving / Construction Construction 165003015600117 Tagbilaran North Rd (Tagbilaran-Jetafe Sect) - K0026+000 - K0027+ P00003476VS-CW1 Off-Carriageway Square meters 6,828 49,500,000 Bohol 1st District 540, K0027+850 - K0028+560 - Off-Carriageway Improvement: Improvement: Shoulder Engineering Office / Bohol Shoulder Paving / Construction Paving / Construction 1st District Engineering Office 165003015600225 Jct (TNR) Cortes-Balilihan-Catigbian-Macaas Rd - K0009+-130 - P00003653VS-CW1 Off-Carriageway Square meters 9,777 91,000,000 Region VII / Region VII K0010+382, K0020+000 - K0021+745 - Off-Carriageway Improvement: Shoulder Improvement: Shoulder Paving / Construction Paving / Construction 165003015600226 Jct. (TNR) Maribojoc-Antequera-Catagbacan (Loon) - K0017+445 - P00015037VS-CW1 Off-Carriageway Square meters 3,141 32,000,000 Bohol 1st District K0018+495 - Off-Carriageway Improvement: Shoulder Paving / Improvement: Shoulder Engineering Office / Bohol Construction Paving / Construction 1st District Engineering Office Construction and Maintenance of Bridges along National Roads - Retrofitting/ Strengthening of Permanent Bridges 165003016100100 Camayaan Br. -

Icc-Wcf-Competition-Negros-Oriental-Cci-Philippines.Pdf

World Chambers Competition Best job creation and business development project Negros Oriental Chamber of Commerce and Industry The Philippines FINALIST I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Negros Oriental Chamber of Commerce and Industry Inc. (NOCCI), being the only recognized voice of business in the Province of Negros Oriental, Philippines, developed the TIP PROJECT or the TRADE TOURISM and INVESTMENT PROMOTION ("TIP" for short) PROJECT to support its mission in conducting trade, tourism and investment promotion, business development activities and enhancement of the business environment of the Province of Negros Oriental. The TIP Project was conceptualized during the last quarter of 2013 and was launched in January, 2014 as the banner project of the Chamber to support its new advocacy for inclusive growth and local economic development through job creation and investment promotion. The banner project was coined from the word “tip” - which means giving sound business advice or sharing relevant information and expertise to all investors, businessmen, local government officials and development partners. The TIP Project was also conceptualized to highlight the significant role and contribution of NOCCI as a champion for local economic development and as a banner project of the Chamber to celebrate its Silver 25th Anniversary by December, 2016. For two years, from January, 2015 to December, 2016, NOCCI worked closely with its various partners in local economic development like the Provincial Government, Local Government Units (LGUs), National Government Agencies (NGAs), Non- Government Organizations (NGOs), Industry Associations and international funding agencies in implementing its various job creation programs and investment promotion activities to market Negros Oriental as an ideal investment/business destination for tourism, retirement, retail, business process outsourcing, power/energy and agro-industrial projects. -

009, As Amended by Resolution No

Republic of the Philippines ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSIO San Miguel Avenue, Pasig City IN THE MATTER OF THE APPLICATION FOR CONFIRMATION AND APPROVAL OF CALCULATIONS OF OVER OR UNDER-RECOVERIES IN THE IMPLEMENTATION OF AUTOMATIC COST ADJUSTMENT AND TRUE- UP MECHANISMS AND CORRESPONDING CONFIRMATION PROCESS PURSUANT TO ERC RESOLUTION NO. 16, SERIES OF 2009, AS AMENDED BY RESOLUTION NO. 21, SERIES OF 2010 ERC CASE NO. 2015-027 CF NEGROS ORIENTAL I ELECTRIC COOPERATIVE, DOCKETED INC. (NORECO I), ]j)ll.te:~;.l:..L.?.l!!.!. " Applicant. 11~'~,.... ._.~ ....- il J(------------------------------------J( DECISION Before this Commission is the application filed by the Negros Oriental I Electric Cooperative, Inc. (NORECO I) on 31 March 2015 for confirmation and approval of calculations of over or under- recoveries in the implementation of automatic cost adjustment and true-up mechanisms and corresponding confirmation process pursuant to ERC Resolution NOr' 6, . ries of 2009, as amended by Resolution No. 21, Series of2010 . ERC Case No. 2015-027 CF Decision/26 July 2016 Page 2 Of20 FACTS In the said application, NORECO I alleged, among others, the following: 1. NORECO I is an electric cooperative duly organized and existing under and by virtue of the laws of the Republic of the Philippines, with principal office at Tinaogan, Bindoy, Negros Oriental; 2. NORECO I holds an exclusive franchise to operate an electric light and power distribution service in the municipalities of Negros Oriental, namely: Mabinay, Manjuyod, Bindoy, Ayungon, Tayasan, Jimalalud, La Libertad, Vallehermoso and the cities of Guihulngan, Bais and Canla-on, all in the province ofNegros Oriental; 3. The Commission's Resolution No. -

Or Negros Oriental

CITY CANLAON CITY LAKE BALINSASAYAO KANLAON VOLCANO VALLEHERMOSO Sibulan - The two inland bodies of Canlaon City - is the most imposing water amid lush tropical forests, with landmark in Negros Island and one of dense canopies, cool and refreshing the most active volcanoes in the air, crystal clear mineral waters with Philippines. At 2,435 meters above sea brushes and grasses in all hues of level, Mt. Kanlaon has the highest peak in Central Philippines. green. Balinsasayaw and Danao are GUIHULNGAN CITY 1,000 meters above sea level and are located 20 kilometers west of the LA LIBERTAD municipality of Sibulan. JIMALALUD TAYASAN AYUNGON MABINAY BINDOY MANJUYOD BAIS CITY TANJAY OLDEST TREE BAYAWAN CITY AMLAN Canlaon City - reportedly the oldest BASAY tree in the Philipines, this huge PAMPLONA SAN JOSE balete tree is estimated to be more NILUDHAN FALLS than a thousand years old. SIBULAN Sitio Niludhan, Barangay Dawis, STA. CATALINA DUMAGUETE Bayawan City - this towering cascade is CITY located near a main road. TAÑON STRAIT BACONG ZAMBOANGUITA Bais City - Bais is popular for its - dolphin and whale-watching activities. The months of May and September are ideal months SIATON for this activity where one can get a one-of-a kind experience PANDALIHAN CAVE with the sea’s very friendly and intelligent creatures. Mabinay - One of the hundred listed caves in Mabinay, it has huge caverns, where stalactites and stalagmites APO ISLAND abound. The cave is accessible by foot and has Dauin - An internationally- an open ceiling at the opposite acclaimed dive site with end. spectacular coral gardens and a cornucopia of marine life; accessible by pumpboat from Zamboanguita. -

PESO-Region 7

REGION VII – PUBLIC EMPLOYMENT SERVICE OFFICES PROVINCE PESO Office Classification Address Contact number Fax number E-mail address PESO Manager Local Chief Executive Provincial Capitol , (032)2535710/2556 [email protected]/mathe Cebu Province Provincial Cebu 235 2548842 [email protected] Mathea M. Baguia Hon. Gwendolyn Garcia Municipal Hall, Alcantara, (032)4735587/4735 Alcantara Municipality Cebu 664 (032)4739199 Teresita Dinolan Hon. Prudencio Barino, Jr. Municipal Hall, (032)4839183/4839 Ferdinand Edward Alcoy Municipality Alcoy, Cebu 184 4839183 [email protected] Mercado Hon. Nicomedes A. de los Santos Municipal Alegria Municipality Hall, Alegria, Cebu (032)4768125 Rey E. Peque Hon. Emelita Guisadio Municipal Hall, Aloquinsan, (032)4699034 Aloquinsan Municipality Cebu loc.18 (032)4699034 loc.18 Nacianzino A.Manigos Hon. Augustus CeasarMoreno Municipal (032)3677111/3677 (032)3677430 / Argao Municipality Hall, Argao, Cebu 430 4858011 [email protected] Geymar N. Pamat Hon. Edsel L. Galeos Municipal Hall, (032)4649042/4649 Asturias Municipality Asturias, Cebu 172 loc 104 [email protected] Mustiola B. Aventuna Hon. Allan L. Adlawan Municipal (032)4759118/4755 [email protected] Badian Municipality Hall, Badian, Cebu 533 4759118 m Anecita A. Bruce Hon. Robburt Librando Municipal Hall, Balamban, (032)4650315/9278 Balamban Municipality Cebu 127782 (032)3332190 / Merlita P. Milan Hon. Ace Stefan V.Binghay Municipal Hall, Bantayan, melitanegapatan@yahoo. Bantayan Municipality Cebu (032)3525247 3525190 / 4609028 com Melita Negapatan Hon. Ian Escario Municipal (032)4709007/ Barili Municipality Hall, Barili, Cebu 4709008 loc. 130 4709006 [email protected] Wilijado Carreon Hon. Teresito P. Mariñas (032)2512016/2512 City Hall, Bogo, 001/ Bogo City City Cebu 906464033 [email protected] Elvira Cueva Hon. -

COMMUNITY-BASED MARINE SANCTUARIES in the PHILIPPINES:A REPORT on FOCUS GROUP DISCUSSIONS

COMMUNITY-BASED MARINE SANCTUARIES in the PHILIPPINES:A REPORT on FOCUS GROUP DISCUSSIONS Brian Crawford, Miriam Balgos and Cesario R. Pagdilao June 2000 Coastal Resources Center Philippine Council for Aquatic and University of Rhode Island Marine Research and Development 1. Introduction 1.1 Project Overview The Coastal Resources Center of the University of Rhode Island (CRC) was awarded a three-year grant in September 1999, from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation to foster marine conservation in Indonesia. The overall goal of the project is to build local capacity in North Sulawesi Province to establish and successfully implement community- based marine sanctuaries. The project builds on previous and on-going CRC field activities in North Sulawesi supported by the USAID Coastal Resources Management Project, locally known as Proyek Pesisir. While the primary emphasis of the project is on Indonesia, it includes a significant Philippine component in the first year. The project objectives are to: • Document methodologies and develop materials for use in widespread adaptation of community-based marine sanctuary approaches to specific site conditions • Build capacity of local institutions in North Sulawesi to replicate models of successful community-based marine sanctuaries by developing human resource capacity and providing supporting resource materials • Replicate small-scale community-based marine sanctuaries in selected North Sulawesi communities through on-going programs of local institutions Activities in the first year of the project are focusing on documenting the limited Indonesia experience and the more than two decades of Philippine experience in establishing and replicating community-based marine sanctuaries. The Philippine experience is highly relevant to Indonesia for several reasons. -

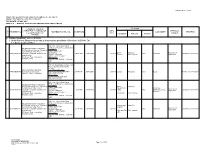

Item Indicators Amlan Ayungon Bacong Bais (City) Basay Bayawan (City) Bindoy Dauin Dumaguete (City)Guihulngan (City) Jimalalud L

Item Indicators Amlan Ayungon Bacong Bais (city) Basay Bayawan (city) Bindoy Dauin Dumaguete (city)Guihulngan (city) Jimalalud Libertad Manjuyod San Jose Santa Catalina Siaton Sibulan Tanjay (city) Tayasan Vallenermoso Zamboanguita 1.1 M/C Fisheries Ordinance Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes 1.2 Ordinance on MCS Yes Yes Yes No No Yes Yes Yes Yes No No No No Yes Yes No Yes No Yes No Yes 1.3a Allow Entry of CFV No N/A No No Yes No Yes No No No No No No Yes No Yes No No No No Yes 1.3b Existence of Ordinance No No No No No No Yes No No N/A No No Yes No No No No No No Yes 1.4a CRM Plan Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes 1.4b ICM Plan Yes No No No No No No No No No Yes No Yes No Yes No N/A Yes No No 1.4c CWUP No No No No No No No No No No Yes No Yes No Yes No N/A Yes No No 1.5 Water Delineation Yes Yes No No No Yes Yes Yes No No No No Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes No Yes 1.6a Registration of fisherfolk Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes 1.6b List of org/coop/NGOs Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes 1.7a Registration of Boats Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes 1.7b Licensing of Boats Yes Yes No No No Yes Yes Yes No No N/A Yes No Yes No Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes 1.7c Fees for Use of Boats Yes Yes No No No Yes No Yes No No No Yes No Yes Yes Yes No Yes No Yes Yes 1.8a Licensing of Gears Yes No No No No Yes Yes Yes No -

A. MINING TENEMENT APPLICATIONS 1. Under Process (Returned Pursuant to the Pertinent Provisions of Section 4 of EO No

ANNEX B Page 1 of 105 MINES AND GEOSCIENCES BUREAU REGIONAL OFFICE NO. VII MINING TENEMENTS STATISTICS REPORT FOR MONTH OF MAY, 2017 ANNEX B - MINERAL PRODUCTION SHARING AGREEMENT (MPSA) TENEMENT HOLDER/ LOCATION line PRESIDENT/ CHAIRMAN OF AREA PREVIOUS TENEMENT NO. ADDRESS/FAX/TEL. NO. DATE FILED COMMODITY REMARKS no. THE BOARD/CONTACT (has.) Barangay/s Mun./City Province HOLDER PERSON A. MINING TENEMENT APPLICATIONS 1. Under Process (Returned pursuant to the pertinent provisions of Section 4 of EO No. 79) 1.1. By the Regional Office 25th Floor, Petron Mega Plaza 358 Sen. Gil Puyat Ave., Makati City Apo Land and Quarry Corporation Cebu Office: Mr. Paul Vincent Arcenas - President Tinaan, Naga, Cebu Contact Person: Atty. Elvira C. Contact Nos.: Bairan Naga City Apo Cement 1 APSA000011VII Oquendo - Corporate Secretary and 06/03/1991 10/02/2009 240.0116 Cebu Limestone Returned on 03/31/2016 (032)273-3300 to 09 Tananas San Fernando Corporation Legal Director FAX No. - (032)273-9372 Mr. Gery L. Rota - Operations Manila Office: Manager (Cebu) (632)849-3754; FAX No. - (632)849- 3580 6th Floor, Quad Alpha Centrum, 125 Pioneer St., Mandaluyong City Tel. Nos. Atlas Consolidated Mining & Cebu Office (Mine Site): 2 APSA000013VII Development Corporation (032) 325-2215/(032) 467-1408 06/14/1991 01/11/2008 287.6172 Camp-8 Minglanilla Cebu Basalt Returned on 03/31/2016 Alfredo C. Ramos - President FAX - (032) 467-1288 Manila Office: (02)635-2387/(02)635-4495 FAX - (02) 635-4495 25th Floor, Petron Mega Plaza 358 Sen. Gil Puyat Ave., Makati City Apo Land and Quarry Corporation Cebu Office: Mr. -

Natural Resources 51

50 CHAPTER 4 NATURAL RESOURCES 51 Chapter 4 NATURAL RESOURCES his chapter provides background information on the status of the mineral resources, forest resources, and coastal resources in the profile area, which t help determine the best resource use and approach to resource management. MINERAL RESOURCES The province of Negros Oriental has a variety of mineral resources of important economic value with copper topping the list. In the profile area, minor deposits of copper are found in the Manjuyod, Sibulan, Bacong, and Dauin area (OPA 1990). Iron and its related compounds of magnetite, pyrite, and marcasite are also found in Sibulan. Solar salt is made in Tanjay, Bais City, and Manjuyod. Other deposits include limestone, dolomite, diatomite, manganese, galena, gypsum, phosphate, and china clay (OPA 1990). Commercial deposits of red burning clay are mostly found in the southeastern portion of Negros Oriental; however, some deposits are spread throughout the profile area. Sand and gravel is also extracted from municipalities in the province and in the profile area. A total of 103,000 m3 of sand and gravel has been extracted in recent years (PPDO 1999). UPLAND FOREST RESOURCES Total good forestland in the province of Negros Oriental is believed to be only 5 percent (27,011 ha) of the total land area of the province (540,230 ha). This low forest cover is due to illegal logging activities that are difficult to stop despite government efforts to formulate laws and enforce prohibition. According to PPDO (1992), forestland is 281,386 ha and is broken down into 5 categories. The categories and the respective areas are summarized in Table 4.1. -

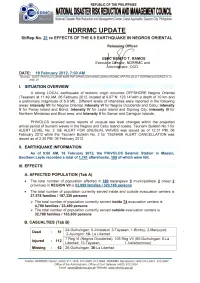

NDRRMC Update Sitrep No.21 on Negros 6.9 Earthquake As Of

C. STATUS OF ROADS AND BRIDGES AND OTHER PUBLIC AND PRIVATE STRUCTURES The estimated total cost of damages incurred by both passable and impassable roads and bridges, public buildings, and flood control structures was pegged PHP 383,059,000.00 INFRASTRUCTURE Region/Province/ PUBLIC TOTAL COST City/Municipality ROADS BRIDGES BUILDINGS GRAND TOTAL 116,825,000.00 168,034,000.00 98,200,000.00 383,059,000.00 Region VI 1,200,000.00 1,200,000.00 Negros Occidental 1,200,000.00 1,200,000.00 Region VII 116,825,000.00 168,034,000.00 97,000,000.00 381,859,000.00 Cebu 1,950,000.00 15,750,000.00 17,700,000.00 Negros Oriental 114,875,000.00 152,284,000.00 97,000,000.00 364,159,000.00 • IMPASSABLE BRIDGES: Two (2) bridges in Negros Oriental remain impassable due to collapsed span of Martilo Bridge in La Libertad and collapsed center span of Pangaloan Bridge in Jimalalud . Delivery of bailey panels from other District Engineering Offices is scheduled for use in the construction of detour bridges. • IMPASSABLE ROAD: One (1) road section along Dumaguete North road remains inaccessible due to cracks/ cuts, rockfalls, landslides and road slips. Restoration works are ongoing. D. DAMAGED HOUSES (Tab C) • A total of 15,787 houses were damaged (Totally – 6,352 / Partially – 9,435) E. STATUS OF LIFELINES • NGCP restored power transmission services in parts of Negros Oriental affected by earthquake. As of 1:56PM, 11 February 2012 normal operations of the Negros sub-grid was restored after completion of repairs and re-energization of the Bindoy-Guihulngan 69-kV transmission line • As of 9 February 2012, some portions of La libertad and Jimalalud were already energized thru the efforts of the National Grid Corp. -

Tañon Strait

Love Letter to TAÑON STRAIT Stacy K. Baez, Ph.D., Charlotte Grubb, Margot L. Stiles and Gloria Ramos Tañon Strait PROTECTED SEASCAPE Bantayan Santa Fe Daanbantayan Medellin The Largest Marine Protected Area Visayan Sea IN THE PHILIPPINES San Remigio Cadiz Sagay Escalante Tabuela Tuburan Toboso Bacolod Asturias San Carlos Balambam Vallehermoso Toledo Cebu Pinamungahan Aloguinsan Gulhulngan Barili La Libertad Dumanjug Aloguinsan Jimalalud Ronda Tayasan Pescador Island Moalboal Ayungon Badian Bindoy Mantalip Reef Alegria Manjuyod Malabuyoc Bais Ginatilan Talabong Mangrove Park Tanjay Samboan Pamplona Amlan Santander San Jose Sibulan Dumaguete Bohol Sea 1 PH.OCEANA.ORG Modified from L. Aragones Introduction Bantayan Santa Fe Daanbantayan Medellin The Largest Marine Protected Area Visayan Sea IN THE PHILIPPINES San Remigio Cadiz Sagay Escalante Tabuela añon Strait Protected Seascape Colorful bangkas grace blue waters is the largest marine protected teeming with fish, and thatched roof Tuburan Toboso Tarea in the Philippines, and the nipa huts shelter families of farmers Bacolod third largest park, nearly as extensive as and fisherfolk all along the shorelines the two largest terrestrial natural parks of Negros and Cebu. Tañon Strait was Asturias in the Northern Sierra Madre and Samar declared a protected seascape in 1998, Island which protect the Philippine in honor of the 14 species of whales and Balambam San Carlos Eagle and other wonders. Tañon Strait dolphins which live within this special is their marine counterpart, with an area place. Several of the Philippines’ most 2 Vallehermoso Toledo of 5,182 km , more than three times the ancient and endangered animals have area of the Tubbataha National Park. -

Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population BOHOL 1,255,128 ALBURQUERQUE 9,921 Bahi 787 Basacdacu 759 Cantiguib 5

2010 Census of Population and Housing Bohol Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population BOHOL 1,255,128 ALBURQUERQUE 9,921 Bahi 787 Basacdacu 759 Cantiguib 555 Dangay 798 East Poblacion 1,829 Ponong 1,121 San Agustin 526 Santa Filomena 911 Tagbuane 888 Toril 706 West Poblacion 1,041 ALICIA 22,285 Cabatang 675 Cagongcagong 423 Cambaol 1,087 Cayacay 1,713 Del Monte 806 Katipunan 2,230 La Hacienda 3,710 Mahayag 687 Napo 1,255 Pagahat 586 Poblacion (Calingganay) 4,064 Progreso 1,019 Putlongcam 1,578 Sudlon (Omhor) 648 Untaga 1,804 ANDA 16,909 Almaria 392 Bacong 2,289 Badiang 1,277 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Bohol Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population Buenasuerte 398 Candabong 2,297 Casica 406 Katipunan 503 Linawan 987 Lundag 1,029 Poblacion 1,295 Santa Cruz 1,123 Suba 1,125 Talisay 1,048 Tanod 487 Tawid 825 Virgen 1,428 ANTEQUERA 14,481 Angilan 1,012 Bantolinao 1,226 Bicahan 783 Bitaugan 591 Bungahan 744 Canlaas 736 Cansibuan 512 Can-omay 721 Celing 671 Danao 453 Danicop 576 Mag-aso 434 Poblacion 1,332 Quinapon-an 278 Santo Rosario 475 Tabuan 584 Tagubaas 386 Tupas 935 Ubojan 529 Viga 614 Villa Aurora (Canoc-oc) 889 National Statistics Office 2 2010 Census of Population and Housing Bohol Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and