Liveable and Sustainable Cities: a Framework” Is an Attempt to Share with the Rest of the World Four Key Pieces of Singapore’S Urbanisation Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tan Wah Piow, Smokescreens & Mirrors: Tracing the “Marxist

ASIATIC, VOLUME 7, NUMBER 1, JUNE 2013 Tan Wah Piow, Smokescreens & Mirrors: Tracing the “Marxist Conspiracy.” Singapore: Function 8 Limited, 2012. 172 pp. ISBN 978-981-07-2104-6. On May 21, 1987, in an operation code named “Spectrum,” Singapore’s Internal Security Department (ISD) detained 16 Singaporeans under the International Security Act (ISA). Six more people were arrested the very next month. The government accused these 22-English educated Singaporeans of being involved in a Marxist plot under the leadership of Tan Wah Piow, a self- styled Maoist, and a dissident Singaporean student leader living in the United Kingdom (UK). He was released from prison in 1976 after serving out a jail term of two years for rioting. As soon as he was released from jail, Tan Wah Piow was served with the call-up notice for National Service (NS), which is compulsory for all male Singapore citizens of 18 years and above. But instead of joining the NS, he fled to the UK in 1976, and sought and given political asylum. He has remained there ever since and is now a British citizen. On 26 May, 1987, Singapore’s Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) released a 41-page press statement justifying the detention without trial of the original 16. They were accused of knowing Catholic Church social worker Vincent Cheng, who in turn was alleged to be receiving orders from Tan Wah Piow to organise a network of young people who were inclined towards Marxism, with the objective of capturing political power after Lee Kuan Yew was no longer the prime minister (Lai To 205). -

2 Parks & Waterbodies Plan

SG1 Parks & Waterbodies Plan AND IDENTITY PLAN S UBJECT G ROUP R EPORT O N PARKS & WATERBODIES PLAN AND R USTIC C OAST November 2002 SG1 SG1 S UBJECT G ROUP R EPORT O N PARKS & WATERBODIES PLAN AND R USTIC C OAST November 2002 SG1 SG1 SG1 i 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 The Parks & Waterbodies Plan and the Identity Plan present ideas and possibilities on how we can enhance our living environment by making the most of our natural assets like the greenery and waterbodies and by retaining places with local identity and history. The two plans were put to public consultation from 23 July 2002 to 22 October 2002. More than 35,000 visited the exhibition, and feedback was received from about 3,600 individuals. Appointment of Subject Groups 1.2 3 Subject Groups (SGs) were appointed by Minister of National Development, Mr Mah Bow Tan as part of the public consultation exercise to study proposals under the following areas: a. Subject Group 1: Parks and Waterbodies Plan and the Rustic Coast b. Subject Group 2: Urban Villages and Southern Ridges & Hillside Villages c. Subject Group 3: Old World Charm 1.3 The SG members, comprising professionals, representatives from interest groups and lay people were tasked to study the various proposals for the 2 plans, conduct dialogue sessions with stakeholders and consider public feedback, before making their recommendations to URA on the proposals. Following from the public consultation exercise, URA will finalise the proposals and incorporate the major land use changes and ideas into the Master Plan 2003. -

Singapore Study Tour 21 - 27 Aug 2017 Contents

Singapore Study Tour 21 - 27 Aug 2017 Contents Forewords P. 4 History of ASHRAE Study Tours P. 5 Acknowledgments P. 6 Executive Summary P. 7 Introduction P. 8 - 9 Itinerary P. 10 - 11 Our tour ended. Tour Experiences P. 12 - 32 Reflections P. 33 - 69 Gallery P. 70 - 74 2 3 Forewords History of ASHRAE Study Tour Hong Kong and Singapore are two fast growing economies in Asia. Although 2017 21 - 27 Aug 2017 (Mon-Sun) broadly similar in historical background and economic structure, the two Singapore Study Tour economies are very different in social, economic and political development patterns. This Singapore Study Tour provided a good opportunity for the Hong Kong students to explore and experience Singapore from different 2015 17 - 23 Aug 2015 (Mon-Sun) angles. Philippines Study Tour This is the eleventh year that the ASHRAE Student Branches in Hong 2014 10 - 17 Aug 2014 (Sun-Sun) Kong organized such a study tour, with the aim to promote student Taiwan Study Tour development, cultural exchange and mutual understanding. The study tour has enabled the participants to visit the government facilities, major universities and recent developments in Singapore. Also, they have 2013 26 Aug - 1 Sep 2013 (Mon-Sun) attended the ASHRAE Region XIII Chapters Regional Conference and Indonesia Study Tour interacted with the ASHRAE student representatives and delegates from Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand and USA. The 2012 9 - 15 Aug 2012 (Thu-Wed) study tour allows the Hong Kong students to exchange ideas with peer Malaysia Study Tour groups and professionals through the ASHRAE community. -

Singapore's Chinese-Speaking and Their Perspectives on Merger

Chinese Southern Diaspora Studies, Volume 5, 2011-12 南方華裔研究雜志, 第五卷, 2011-12 “Flesh and Bone Reunite as One Body”: Singapore’s Chinese- speaking and their Perspectives on Merger ©2012 Thum Ping Tjin* Abstract Singapore’s Chinese speakers played the determining role in Singapore’s merger with the Federation. Yet the historiography is silent on their perspectives, values, and assumptions. Using contemporary Chinese- language sources, this article argues that in approaching merger, the Chinese were chiefly concerned with livelihoods, education, and citizenship rights; saw themselves as deserving of an equal place in Malaya; conceived of a new, distinctive, multiethnic Malayan identity; and rejected communist ideology. Meanwhile, the leaders of UMNO were intent on preserving their electoral dominance and the special position of Malays in the Federation. Finally, the leaders of the PAP were desperate to retain power and needed the Federation to remove their political opponents. The interaction of these three factors explains the shape, structure, and timing of merger. This article also sheds light on the ambiguity inherent in the transfer of power and the difficulties of national identity formation in a multiethnic state. Keywords: Chinese-language politics in Singapore; History of Malaya; the merger of Singapore and the Federation of Malaya; Decolonisation Introduction Singapore’s merger with the Federation of Malaya is one of the most pivotal events in the country’s history. This process was determined by the ballot box – two general elections, two by-elections, and a referendum on merger in four years. The centrality of the vote to this process meant that Singapore’s Chinese-speaking1 residents, as the vast majority of the colony’s residents, played the determining role. -

Expat Singapore.Pdf

SINGAPORE An everyday guide to expatriate life and work. YOUR SINGAPORE COUNTRY GUIDE Contents Overview 1 Employment Quick Facts 1 The job market 7 Getting Started Income tax 7 Climate and weather 2 Business etiquette 7 Visas 3 Retirement 7 Accommodation 3 Finance Schools 3 Currency 8 Culture Cost of living 8 Language 4 Banking 8 Social etiquette and faux pas 4 Cost of living chart 9 Eating 4 Drinking 4 Health Holidays 5 Private Medical Insurance 8 Emergencies BC Transport 6 Vaccinations BC Getting In Touch Health Risks BC Telephone 6 Pharmacies BC Internet 6 Postal services 6 Quick facts Capital: Singapore Population: 5.6 million Major language: English, Malay, Mandarin and Tamil Major religion: Buddhism, Christianity Currency: Singapore Dollar (SGD) Time zone: GMT+8 Emergency number: 999 (police), 995 (ambulance, fire) Electricity: 230 volts, 50Hz. Three-pin plugs with flat blades are used. Drive on the: Left http://www.expatarrivals.com/singapore/essential- info-for-singapore Overview Singapore is a buzzing metropolis with a fascinating mix of nationalities and cultures that promote tolerance and harmony. Expats can take comfort in the knowledge that the island city- state is clean and safe. Renowned for its exemplary and efficient public transport and communications infrastructure, Singapore is also home to some of the best international schools and healthcare facilities in the world. In the tropical climate that Singapore boasts, expats can look forward to a relaxed, outdoor lifestyle all year round. Its location, situated off the southern coast of Malaysia, also makes Singapore an ideal base from which to explore other parts of Asia. -

A Special Issue to Commemorate Singapore Bicentennial 2019

2019 A Special Issue to Commemorate Singapore Bicentennial 2019 About the Culture Academy Singapore Te Culture Academy Singapore was established in 2015 by the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth to groom the next generation of cultural leaders in the public sector. Guided by its vision to be a centre of excellence for the development of culture professionals and administrators, the Culture Academy Singapore’s work spans three areas: Education and Capability Development, Research and Scholarship and Tought Leadership. Te Culture Academy Singapore also provides professional development workshops, public lectures and publishes research articles through its journal, Cultural Connections, to nurture thought leaders in Singapore’s cultural scene. One of the Academy’s popular oferings is its annual thought leadership conference which provides a common space for cultural leaders to gather and exchange ideas and best practices, and to incubate new ideas. It also ofers networking opportunities and platforms for collaborative ideas-sharing. Cultural Connections is a journal published annually by the Culture Academy Singapore to nurture thought leadership in cultural work in the public sector. Te views expressed in the publication are solely those of the authors and contributors, and do not in any way represent the views of the National Heritage Board or the Singapore Government. Editor-in-Chief: Tangamma Karthigesu Editor: Tan Chui Hua Editorial Assistants: Geraldine Soh & Nur Hummairah Design: Fable Printer: Chew Wah Press Distributed by the Culture Academy Singapore Published in July 2019 by Culture Academy Singapore, 61 Stamford Road #02-08 Stamford Court Singapore 178892 © 2019 National Heritage Board. All rights reserved. National Heritage Board shall not be held liable for any damages, disputes, loss, injury or inconvenience arising in connection with the contents of this publication. -

World Cities Summit 2016

BETTER CITIES Your monthly update from the Centre for Liveable Cities Issue 67 July 2016 World Cities Summit 2016 The World Cities Summit 2016, co-organised by the Centre for Liveable Cities and the Urban Redevelopment Authority, attracted about 110 mayors and city leaders representing 103 cities from 63 countries and regions around the world to engage on issues of urban sustainability. Held from 10-14 July, the fifth edition of the World Cities Summit, together with Singapore International Water Week (SIWW) and CleanEnviro Summit Singapore (CESS), was attended by more than 21,000 visitors and participants including ministers, government officials, industry leaders and experts, academics, as well as representatives from international organisations. Themed ‘Liveable and Sustainable Cities: Innovative Cities of Opportunity’, this year’s Summit expanded its focus on how cities can leverage innovations to build smart cities. A key highlight of the expo was the ‘Towards a Smart and Sustainable Singapore’ pavilion, which showcased innovations from more than 16 Singapore government agencies designed to help serve citizens better. WCS 2016 also explored the strategy of co-creation and how cities can better engage their citizens to build more resilient cities beyond infrastructure alone. For the first time at WCS, the impact of softer aspects of a city like culture and heritage on urban planning and design was discussed at a dedicated track. The next World Cities Summit will be held from 8-12 July 2018 at the Sands Expo and Convention Centre, Singapore. Click here for the WCS 2016 press release. Enabling Technologies: A Prototype for Urban Planning By Zhou Yimin CLC is working with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) on an interactive urban planning tool that creates realistic simulations of planning decisions and allows planners to understand the implications for their city. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “ Missing Page(s)“ . If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in “sectioning" the material. It is customary tc begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from “ photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

The Complex Expression of Singapore's Contemporary Daily Life and Culture Through Animation

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Animating Singapore : the complex expression of Singapore's contemporary daily life and culture through animation Goh, Wei Choon 2017 Goh, W. C. (2017). Animating Singapore : the complex expression of Singapore's contemporary daily life and culture through animation. Master's thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. http://hdl.handle.net/10356/72490 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/72490 Downloaded on 10 Oct 2021 04:01:50 SGT ATTENTION: The Singapore Copyright Act applies to the use of this document. Nanyang Technological University Library Animating Singapore: The complex expression of Singapore's contemporary daily life and culture through animation. GOH WEI CHOON SCHOOL OF ART, DESIGN & MEDIA A thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts 2017 (Year of Submission of Hard Bound Thesis) 1 ATTENTION: The Singapore Copyright Act applies to the use of this document. Nanyang Technological University Library Acknowledgements Firstly, I would like to thank my supervisor, Hans-Martin Rail for his tireless support and encouragement. He has been a steadfast anchor for my post-graduate endeavors, and I would not have made it this far without his guidance as a mentor on academia, animation and life. Professor Ishu Patel was an important spiritual guide for my soul. He provided me with the ethical and artistic basis that I keep close to my heart at all times to remind myself of my power, role and responsibilities as an animator and artist. -

MARUAH Singapore

J U N E 2012 DEFINED MARUAH FROM THE PRESIDENT’S DESK ignity is starving. It needs detainees to varying grades of Dattention. It needs activation. inhuman treatment. Dignity is inherent in the human In this inaugural issue of condition. We all want to live Dignity Defined, MARUAH’s e-news every day in dignity, with dignity magazine, we raise awareness on and hopefully also treat others human rights, human responsibilities with dignity. The challenge to and social justice through discussions realising dignity lies in the around Operation Spectrum. difficulty of conceptualising this I was a teacher when the quality. alleged Marxist Conspiracy broke Dignity - what does it entail, in 1987. I read the newspapers what values does it embody, intently and watched television what principles is it based on, hawkishly as the detentions and how do we hold it in the palm were unravelled. I unpicked and of our hands to own it. We at unpacked the presentations made MARUAH are committed to finding by the government, the Catholic WHAT’S INSIDE? some answers to visualising, Church and the detainees too when conceptualising and discussing they were paraded for television 3 From History.... Dignity. We believe that much confessions. Operation Spectrum of what we can do to activate I was sceptical then and today & the ISA on Dignity comes from a rights- I am still unconvinced that they Rizwan Ahmad based approach to self and to were a national threat. others. As such we premise much It was an awful time. I watched 4 The Internal Security of our work on the aspirations the 22 detainees being ferried Act and the “Marxist of the Universal Declaration of away, from view. -

Islam in a Secular State Walid Jumblatt Abdullah Islam in a Secular State

RELIGION AND SOCIETY IN ASIA Abdullah Islam in a Secular State a Secular in Islam Walid Jumblatt Abdullah Islam in a Secular State Muslim Activism in Singapore Islam in a Secular State Religion and Society in Asia This series contributes cutting-edge and cross-disciplinary academic research on various forms and levels of engagement between religion and society that have developed in the regions of South Asia, East Asia, and South East Asia, in the modern period, that is, from the early 19th century until the present. The publications in this series should reflect studies of both religion in society and society in religion. This opens up a discursive horizon for a wide range of themes and phenomena: the politics of local, national and transnational religion; tension between private conviction and the institutional structures of religion; economical dimensions of religion as well as religious motives in business endeavours; issues of religion, law and legality; gender relations in religious thought and practice; representation of religion in popular culture, including the mediatisation of religion; the spatialisation and temporalisation of religion; religion, secularity, and secularism; colonial and post-colonial construction of religious identities; the politics of ritual; the sociological study of religion and the arts. Engaging these themes will involve explorations of the concepts of modernity and modernisation as well as analyses of how local traditions have been reshaped on the basis of both rejecting and accepting Western religious, -

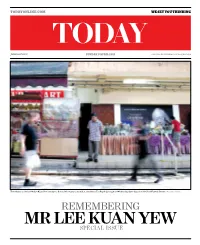

Lee Kuan Yew Continue to flow As Life Returns to Normal at a Market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, Three Days After the State Funeral Service

TODAYONLINE.COM WE SET YOU THINKING SUNDAY, 5 APRIL 2015 SPECIAL EDITION MCI (P) 088/09/2014 The tributes to the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew continue to flow as life returns to normal at a market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, three days after the State Funeral Service. PHOTO: WEE TECK HIAN REMEMBERING MR LEE KUAN YEW SPECIAL ISSUE 2 REMEMBERING LEE KUAN YEW Tribute cards for the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew by the PCF Sparkletots Preschool (Bukit Gombak Branch) teachers and students displayed at the Chua Chu Kang tribute centre. PHOTO: KOH MUI FONG COMMENTARY Where does Singapore go from here? died a few hours earlier, he said: “I am for some, more bearable. Servicemen the funeral of a loved one can tell you, CARL SKADIAN grieved beyond words at the passing of and other volunteers went about their the hardest part comes next, when the DEPUTY EDITOR Mr Lee Kuan Yew. I know that we all duties quietly, eiciently, even as oi- frenzy of activity that has kept the mind feel the same way.” cials worked to revise plans that had busy is over. I think the Prime Minister expected to be adjusted after their irst contact Alone, without the necessary and his past week, things have been, many Singaporeans to mourn the loss, with a grieving nation. fortifying distractions of a period of T how shall we say … diferent but even he must have been surprised Last Sunday, about 100,000 people mourning in the company of others, in Singapore. by just how many did.