Ismail Merchant: Film Producer Extraordinary / Partha Chatterjee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Oscar-Winning 'Slumdog Millionaire:' a Boost for India's Global Image?

ISAS Brief No. 98 – Date: 27 February 2009 469A Bukit Timah Road #07-01, Tower Block, Singapore 259770 Tel: 6516 6179 / 6516 4239 Fax: 6776 7505 / 6314 5447 Email: [email protected] Website: www.isas.nus.edu.sg Oscar-winning ‘Slumdog Millionaire’: A Boost for India’s Global Image? Bibek Debroy∗ Culture is difficult to define. This is more so in a large and heterogeneous country like India, where there is no common language and religion. There are sub-cultures within the country. Joseph Nye’s ‘soft power’ expression draws on a country’s cross-border cultural influences and is one enunciated with the American context in mind. Almost tautologically, soft power implies the existence of a relatively large country and the term is, therefore, now also being used for China and India. In the Indian case, most instances of practice of soft power are linked to language and literature (including Indians writing in English), music, dance, cuisine, fashion, entertainment and even sport, and there is no denying that this kind of cross-border influence has been increasing over time, with some trigger provided by the diaspora. The film and television industry’s influence is no less important. In the last few years, India has produced the largest number of feature films in the world, with 1,164 films produced in 2007. The United States came second with 453, Japan third with 407 and China fourth with 402. Ticket sales are higher for Bollywood than for Hollywood, though revenue figures are much higher for the latter. Indian film production is usually equated with Hindi-language Bollywood, often described as the largest film-producing centre in the world. -

Over His Long Career, the Icon of American Cinema Defined a Style of Filmmaking That Embraced the Burnished Heights of Society, Culture, and Sophistication

JAMES IVORY OVER HIS LONG CAREER, THE ICON OF AMERICAN CINEMA DEFINED A STYLE OF FILMMAKING THAT EMBRACED THE BURNISHED HEIGHTS OF SOCIETY, CULTURE, AND SOPHISTICATION. BUT JAMES IVORY AND HIS LATE PARTNER, ISMAIL MERCHANT, WERE ALSO INVETERATE OUTSIDERS WHOSE ART WAS AS POLITICALLY PROVOCATIVE AS IT WAS VISUALLY MANNERED. AT AGE 88, THE WRITER-DIRECTOR IS STILL BRINGING STORIES TO THE SCREEN THAT FEW OTHERS WOULD DARE. By CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN Photography SEBASTIAN KIM JAMES IVORY IN CLAVERACK, NY, FEBRUARY 2017. COAT: JEFFREY RUDES. SHIRT: IVORY’S OWN. On a mantle in James Ivory’s country house in but also managed to provoke, astonish, and seduce. the depths of winter. It just got to be too much, and I IVORY: I go all the time. I suppose it’s the place I love IVORY: I saw this collection of Indian miniature upstate New York sits a framed photo of actress In the case of Maurice, perhaps because the film was remember deciding to go back to New York to work most in the world. When I went to Europe for the paintings in the gallery of a dealer in San Francisco. Maggie Smith, dressed up in 1920s finery, from the so disarmingly refined and the quality of the act- on Surviving Picasso. first time, I went to Paris and then to Venice. So after I was so captivated by them. I thought, “Gosh, I’ll set of Ivory’s 1981 filmQuartet . By the fireplace in an ing and directing so strong, its central gay love story BOLLEN: The winters up here can be bleak. -

The Communalization and Disintegration of Urdu in Anita Desai’S in Custody 1

The Communalization and Disintegration of Urdu in Anita Desai’s In Custody 1 Introduction T of Urdu in India is an extremely layered one which needs to be examined historically, politically and ideologically in order to grasp the various forces which have shaped its current perception as a sectarian language adopted by Indian Muslims, marking their separation from the national collectivity. In this article I wish to explore these themes through the lens of literature, specifically an Indian English novel about Urdu entitled In Custody by Anita Desai. Writing in the early s, Aijaz Ahmad was of the opinion that the teaching of English literature has cre- ated a body of English-speaking Indians who represent “the only” over- arching national community with a common language, able to imagine themselves across the disparate nation as a “national literary intelligentsia” with “a shared body of knowledge, shared presumptions and a shared knowledge of mutual exchange” (, ).2 Arguably both Desai and Ahmad belong to this “intelligentsia” through the postcolonial secular English connection, but equally they are implicated in the discursive structures of cultural hegemony in civil society (Viswanathan , –; Rajan , –). However, it is not my intention to re-inscribe an authentic myth of origin about Indianness through linguistic associations, 1An earlier version of this essay was first presented as a paper at the Minori- ties, Education and Language in st Century Indian Democracy—The Case of Urdu with Special Reference to Dr. Zakir Husain, Late President of India Con- ference held in Delhi, February . 2See also chapter “‘Indian Literature’: Notes Toward the Definition of a Category,” in the same work, –. -

The Secret Scripture

Presents THE SECRET SCRIPTURE Directed by JIM SHERIDAN/ In cinemas 7 December 2017 Starring ROONEY MARA, VANESSA REDGRAVE, JACK REYNOR, THEO JAMES and ERIC BANA PUBLICITY REQUESTS: Transmission Films / Amy Burgess / +61 2 8333 9000 / [email protected] IMAGES High res images and poster available to download via the DOWNLOAD MEDIA tab at: http://www.transmissionfilms.com.au/films/the-secret-scripture Distributed in Australia by Transmission Films Ingenious Senior Film Fund Voltage Pictures and Ferndale Films present with the participation of Bord Scannán na hÉireann/ the Irish Film Board A Noel Pearson production A Jim Sheridan film Rooney Mara Vanessa Redgrave Jack Reynor Theo James and Eric Bana THE SECRET SCRIPTURE Six-time Academy Award© nominee and acclaimed writer-director Jim Sheridan returns to Irish themes and settings with The Secret Scripture, a feature film based on Sebastian Barry’s Man Booker Prize-winning novel and featuring a stellar international cast featuring Rooney Mara, Vanessa Redgrave, Jack Reynor, Theo James and Eric Bana. Centering on the reminiscences of Rose McNulty, a woman who has spent over fifty years in state institutions, The Secret Scripture is a deeply moving story of love lost and redeemed, against the backdrop of an emerging Irish state in which female sexuality and independence unsettles the colluding patriarchies of church and nationalist politics. Demonstrating Sheridan’s trademark skill with actors, his profound sense of story, and depth of feeling for Irish social history, The Secret Scripture marks a return to personal themes for the writer-director as well as a reunion with producer Noel Pearson, almost a quarter of a century after their breakout success with My Left Foot. -

Ismail Merchant: Film Producer Extraordinary / Partha Chatterjee,Shabd Leela – the Interplay of Words / Manohar Khushalani,I K

Ismail Merchant: Film Producer Extraordinary / Partha Chatterjee Ismail Merchant with James Ivory Ismail Merchant’s passing away on May 25, 2005 marked the end of a certain kind of cinema. He was the last of the maverick film producers with taste who made without any compromise, films with a strong literary bias which were partial to actors and had fine production values. It is sad that he died at sixty eight of bleeding ulcers unable to any longer work his legendary charm on venal German financiers who were supposed to finance his last production, The White Countess, which was to have been directed by his long-time partner James Ivory. Merchant-Ivory productions came into being in 1961 when, Ismail Merchant, a Bohra Muslim student on a scholarship in America met James Ivory, an Ivy-leaguer with art and cinema on his mind, quite by accident in a New York coffee shop. The rest as they say is history. Together they made over forty films in a relationship that lasted all of forty- four years. A record in the annals of independent filmmaking anywhere in the world. Ivory’s gentle, inward looking vision may never have found expression on the scale that it did but for Merchant’s amazing resourcefulness that included coaxing, cajoling, bullying and charming all those associated, directly and indirectly with the making of his films. Merchant-Ivory productions’ first venture was a documentary, The Delhi Way back in 1962. The next year they made a feature length fiction film The Householder in Black and White. It was about a young college lecturer, tentative and clumsy trying to find happiness with his wife from a sheltered background. -

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala's Adapted Screenplays

Absorbing the Worlds of Others: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s Adapted Screenplays By Laura Fryer Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of a PhD degree at De Montfort University, Leicester. Funded by Midlands 3 Cities and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. June 2020 i Abstract Despite being a prolific and well-decorated adapter and screenwriter, the screenplays of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala are largely overlooked in adaptation studies. This is likely, in part, because her life and career are characterised by the paradox of being an outsider on the inside: whether that be as a European writing in and about India, as a novelist in film or as a woman in industry. The aims of this thesis are threefold: to explore the reasons behind her neglect in criticism, to uncover her contributions to the film adaptations she worked on and to draw together the fields of screenwriting and adaptation studies. Surveying both existing academic studies in film history, screenwriting and adaptation in Chapter 1 -- as well as publicity materials in Chapter 2 -- reveals that screenwriting in general is on the periphery of considerations of film authorship. In Chapter 2, I employ Sandra Gilbert’s and Susan Gubar’s notions of ‘the madwoman in the attic’ and ‘the angel in the house’ to portrayals of screenwriters, arguing that Jhabvala purposely cultivates an impression of herself as the latter -- a submissive screenwriter, of no threat to patriarchal or directorial power -- to protect herself from any negative attention as the former. However, the archival materials examined in Chapter 3 which include screenplay drafts, reveal her to have made significant contributions to problem-solving, characterisation and tone. -

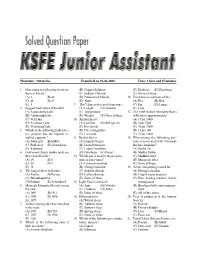

1. How Many West Flowing Rivers Are There in Kerala?

Maximum : 100 marks Exam held on 29-06-2002 Time: 1 hour and 15 minutes 1. How many west flowing rivers are (B) Copper Sulphate (C) Diabetes (D) Diarrhoea there in Kerala? (C) Sodium Chloride (E) None of these (A) 3 (B) 40 (D) Potassium Chloride 16. Trachoma is a disease of the: (C) 41 (D) 21 (E) Alum (A) Eye (B) Skin. (E) 5 9. The Celsius scale is used to measure: (C) Ear (D) Lungs 2. Biggest back water of Kerala? (A) Length (B) Velocity (E) Liver (A) Sastamkotta Lake (C) Temperature 17. The IMR (Infant Mortality Rate) (B) Ashtamudi Lake (D) Weight (E) None of these of Kerala is approximately: (C) Veli Lake 10. Ammonia is a : (A) 13 per 1000 (D) Paravoor Lake (A) Fertilizer (B) Refrigerant (B) 3 per 7000 (E) Vembanad Lake (C) Insecticide (C) 36 per 7000 3. Which of the following hydroelec- (D) Fire extinguisher (D) 13 per 100 tric projects has the highest in- (E) Larvicide (E) 31 per 1000 stalled capacity ? 11. Rocket fuel is : 18. Who among the following per- (A) Sabarigiri (B) Idukki (A) Liquid Oxygen sons is associated with Narmada (C) Pallivasal (D) Edamalayar (B) Liquid Nitrogen Bachao Andolan? (E) Kuttiyadi (C) Liquid Ammonia (A) Shoba De 4. How many Rajya Sabha seats are (D) Petroleum (E) Diesel (B) Medha Patkar there from Kerala ? 12. Which gas is used in the prepara- (C) Madhuri Dixit (A) 14 (B) 5 tion of soda water? (D) Margerret Alva (C) 20 (D) 9 (A) Carbon monoxide (E) None of these (E) 11 (B) Nitrogen dioxide 19. -

February 18, 2014 (Series 28: 4) Satyajit Ray, CHARULATA (1964, 117 Minutes)

February 18, 2014 (Series 28: 4) Satyajit Ray, CHARULATA (1964, 117 minutes) Directed by Satyajit Ray Written byRabindranath Tagore ... (from the story "Nastaneer") Cinematography by Subrata Mitra Soumitra Chatterjee ... Amal Madhabi Mukherjee ... Charulata Shailen Mukherjee ... Bhupati Dutta SATYAJIT RAY (director) (b. May 2, 1921 in Calcutta, West Bengal, British India [now India]—d. April 23, 1992 (age 70) in Calcutta, West Bengal, India) directed 37 films and TV shows, including 1991 The Stranger, 1990 Branches of the Tree, 1989 An Enemy of the People, 1987 Sukumar Ray (Short documentary), 1984 The Home and the World, 1984 (novel), 1979 Naukadubi (story), 1974 Jadu Bansha (lyrics), “Deliverance” (TV Movie), 1981 “Pikoor Diary” (TV Short), 1974 Bisarjan (story - as Kaviguru Rabindranath), 1969 Atithi 1980 The Kingdom of Diamonds, 1979 Joi Baba Felunath: The (story), 1964 Charulata (from the story "Nastaneer"), 1961 Elephant God, 1977 The Chess Players, 1976 Bala, 1976 The Kabuliwala (story), 1961 Teen Kanya (stories), 1960 Khoka Middleman, 1974 The Golden Fortress, 1973 Distant Thunder, Babur Pratyabartan (story - as Kabiguru Rabindranath), 1960 1972 The Inner Eye, 1972 Company Limited, 1971 Sikkim Kshudhita Pashan (story), 1957 Kabuliwala (story), 1956 (Documentary), 1970 The Adversary, 1970 Days and Nights in Charana Daasi (novel "Nauka Doobi" - uncredited), 1947 the Forest, 1969 The Adventures of Goopy and Bagha, 1967 The Naukadubi (story), 1938 Gora (story), 1938 Chokher Bali Zoo, 1966 Nayak: The Hero, 1965 “Two” (TV Short), 1965 The (novel), 1932 Naukadubi (novel), 1932 Chirakumar Sabha, 1929 Holy Man, 1965 The Coward, 1964 Charulata, 1963 The Big Giribala (writer), 1927 Balidan (play), and 1923 Maanbhanjan City, 1962 The Expedition, 1962 Kanchenjungha, 1961 (story). -

Please Turn Off Cellphones During Screening March 6, 2012 (XXIV:8) Satyajit Ray, the MUSIC ROOM (1958, 96 Min.)

Please turn off cellphones during screening March 6, 2012 (XXIV:8) Satyajit Ray, THE MUSIC ROOM (1958, 96 min.) Directed, produced and written by Satyajit Ray Based on the novel by Tarashankar Banerjee Original Music by Ustad Vilayat Khan, Asis Kumar , Robin Majumder and Dakhin Mohan Takhur Cinematography by Subrata Mitra Film Editing by Dulal Dutta Chhabi Biswas…Huzur Biswambhar Roy Padmadevi…Mahamaya, Roy's wife Pinaki Sengupta…Khoka, Roy's Son Gangapada Basu…Mahim Ganguly Tulsi Lahiri…Manager of Roy's Estate Kali Sarkar…Roy's Servant Waheed Khan…Ujir Khan Roshan Kumari…Krishna Bai, dancer SATYAJIT RAY (May 2, 1921, Calcutta, West Bengal, British India – April 23, 1992, Calcutta, West Bengal, India) directed 37 films: 1991 The Visitor, 1990 Branches of the Tree, 1989 An Elephant God (novel / screenplay), 1977 The Chess Players, Enemy of the People, 1987 Sukumar Ray, 1984 The Home and 1976 The Middleman, 1974 The Golden Fortress, 1974 Company the World, 1984 “Deliverance”, 1981 “Pikoor Diary”, 1980 The Limited, 1973 Distant Thunder, 1972 The Inner Eye, 1971 The Kingdom of Diamonds, 1979 Joi Baba Felunath: The Elephant Adversary, 1971 Sikkim, 1970 Days and Nights in the Forest, God, 1977 The Chess Players, 1976 The Middleman, 1976 Bala, 1970 Baksa Badal, 1969 The Adventures of Goopy and Bagha, 1974 The Golden Fortress, 1974 Company Limited, 1973 Distant 1967 The Zoo, 1966 Nayak: The Hero, 1965 Kapurush: The Thunder, 1972 The Inner Eye, 1971 The Adversary, 1971 Sikkim, Coward, 1965 Mahapurush: The Holy Man, 1964 The Big City: 1970 Days -

Été Indien 10E Édition 100 Ans De Cinéma Indien

Été indien 10e édition 100 ans de cinéma indien Été indien 10e édition 100 ans de cinéma indien 9 Les films 49 Les réalisateurs 10 Harishchandrachi Factory de Paresh Mokashi 50 K. Asif 11 Raja Harishchandra de D.G. Phalke 51 Shyam Benegal 12 Saint Tukaram de V. Damle et S. Fathelal 56 Sanjay Leela Bhansali 14 Mother India de Mehboob Khan 57 Vishnupant Govind Damle 16 D.G. Phalke, le premier cinéaste indien de Satish Bahadur 58 Kalipada Das 17 Kaliya Mardan de D.G. Phalke 58 Satish Bahadur 18 Jamai Babu de Kalipada Das 59 Guru Dutt 19 Le vagabond (Awaara) de Raj Kapoor 60 Ritwik Ghatak 20 Mughal-e-Azam de K. Asif 61 Adoor Gopalakrishnan 21 Aar ar paar (D’un côté et de l’autre) de Guru Dutt 62 Ashutosh Gowariker 22 Chaudhvin ka chand de Mohammed Sadiq 63 Rajkumar Hirani 23 La Trilogie d’Apu de Satyajit Ray 64 Raj Kapoor 24 La complainte du sentier (Pather Panchali) de Satyajit Ray 65 Aamir Khan 25 L’invaincu (Aparajito) de Satyajit Ray 66 Mehboob Khan 26 Le monde d’Apu (Apur sansar) de Satyajit Ray 67 Paresh Mokashi 28 La rivière Titash de Ritwik Ghatak 68 D.G. Phalke 29 The making of the Mahatma de Shyam Benegal 69 Mani Ratnam 30 Mi-bémol de Ritwik Ghatak 70 Satyajit Ray 31 Un jour comme les autres (Ek din pratidin) de Mrinal Sen 71 Aparna Sen 32 Sholay de Ramesh Sippy 72 Mrinal Sen 33 Des étoiles sur la terre (Taare zameen par) d’Aamir Khan 73 Ramesh Sippy 34 Lagaan d’Ashutosh Gowariker 36 Sati d’Aparna Sen 75 Les éditions précédentes 38 Face-à-face (Mukhamukham) d’Adoor Gopalakrishnan 39 3 idiots de Rajkumar Hirani 40 Symphonie silencieuse (Mouna ragam) de Mani Ratnam 41 Devdas de Sanjay Leela Bhansali 42 Mammo de Shyam Benegal 43 Zubeidaa de Shyam Benegal 44 Well Done Abba! de Shyam Benegal 45 Le rôle (Bhumika) de Shyam Benegal 1 ] Je suis ravi d’apprendre que l’Auditorium du musée Guimet organise pour la dixième année consécutive le festival de films Été indien, consacré exclusivement au cinéma de l’Inde. -

Revisiting the Experience of Translating Faiz for Merchant-Ivory’S in Custody by Shahrukh Husain

Pakistaniaat: A Journal of Pakistan Studies Vol. 5, No. 1 (2013) Found in Translation: Revisiting the experience of Translating Faiz for Merchant-Ivory’s In Custody By Shahrukh Husain “To recite a verse, you need power, resonance, the explosion of a cannon. There’s a spark or two still left in Urdu.” Nur, In Custody (quoted from film subtitle) It was an odd experience watching In Custody eighteen years after it was premiered at the London Film Festival in 1993. The decision to make this film was unique and crazy. Anita Desai’s Booker-nominated novel of the same title follows the nightmarish journey of a Hindi lecturer, Deven (Om Puri), in the small town of Mirpur whose secret passion for Urdu (“the right to left language”) is suddenly exposed when a roguish magazine editor of an Urdu magazine commissions an interview with Nur Shahjahanabadi (Shashi Kapoor). Nur is the pivotal character of the narrative, once hailed as the ‘poet of the age’, though now he is all but forgotten, having fallen into decadent ways, impoverished, sick and unproductive. Perhaps he has given up on his art, believing that “if Urdu is no more, of what significance is its poetry? It is dead, finished. You see its corpse lying here, waiting to be disposed of.” Nur, In Custody (quoted from film subtitle). Deven is charged with recording any new work by the poet for his magazine and so begins a nightmarish journey in which the lecturer disgraces himself at his university, embarrasses his supporters and alienates even his long-suffering wife.