The Hoanib, Hoarusib and Khumib River Catchments Are the Three Most Northern of the Twelve Major Westerly Flowing Ephemeral

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Instituto Da Cooperação Portuguesa (Portugal)

Instituto da Cooperação Portuguesa (Portugal) Ministério da Energia e Águas de Angola SOUTHERN AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT COMMUNITY PLAN FOR THE INTEGRATED UTILIZATION OF THE WATER RESOURCES OF THE HYDROGRAPHIC BASIN OF THE CUNENE RIVER SYNTHESIS LNEC – Laboratório Nacional de Engenharia Civil Page 1/214 LNEC – Proc.605/1/11926 MINISTÉRIO DO EQUIPAMENTO SOCIAL Laboratório Nacional de Engenharia Civil DEPARTMENT OF HYDRAULICS Section for Structural Hydraulics Proc.605/1/11926 PLAN FOR THE INTEGRATED UTILIZATION OF THE WATER RESOURCES OF THE HYDROGRAPHIC BASIN OF THE CUNENE RIVER Report 202/01 – NHE Lisbon, July 2001 A study commissioned by the Portuguese Institute for Cooperation I&D HYDRAULICS Page 2/214 LNEC – Proc.605/1/11926 PLAN FOR THE INTEGRATED UTILIZATION OF THE WATER RESOURCES OF THE HYDROGRAPHIC BASIN OF THE CUNENE RIVER SYNTHESIS Page 3/214 LNEC – Proc.605/1/11926 PLAN FOR THE INTEGRATED UTILIZATION OF THE WATER RESOURCES OF THE HYDROGRAPHIC BASIN OF THE CUNENE RIVER INTRODUCTORY NOTE This report synthesizes a number of documents that have been elaborated for the Portuguese Institute for Cooperation. The main objective of the work was to establish a Plan for the Integrated Utilization of the Water Resources of the Hydrographic Basin of the Cunene River. As the elaboration of this Plan is a multi-disciplinary task, it was deemed preferable to grant independence of reporting on the work of each team that contributed to the final objective. That is why each report consists of a compilation of volumes. REPORT I VOLUME 1 – SYNTHESIS (discarded) -

Angolan Giraffe (Giraffa Camelopardalis Ssp

Angolan Giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis ssp. angolensis) Appendix 1: Historical and recent geographic range and population of Angolan Giraffe G. c. angolensis Geographic Range ANGOLA Historical range in Angola Giraffe formerly occurred in the mopane and acacia savannas of southern Angola (East 1999). According to Crawford-Cabral and Verissimo (2005), the historic distribution of the species presented a discontinuous range with two, reputedly separated, populations. The western-most population extended from the upper course of the Curoca River through Otchinjau to the banks of the Kunene (synonymous Cunene) River, and through Cuamato and the Mupa area further north (Crawford-Cabral and Verissimo 2005, Dagg 1962). The intention of protecting this western population of G. c. angolensis, led to the proclamation of Mupa National Park (Crawford-Cabral and Verissimo 2005, P. Vaz Pinto pers. comm.). The eastern population occurred between the Cuito and Cuando Rivers, with larger numbers of records from the southeast corner of the former Mucusso Game Reserve (Crawford-Cabral and Verissimo 2005, Dagg 1962). By the late 1990s Giraffe were assumed to be extinct in Angola (East 1999). According to Kuedikuenda and Xavier (2009), a small population of Angolan Giraffe may still occur in Mupa National Park; however, no census data exist to substantiate this claim. As the Park was ravaged by poachers and refugees, it was generally accepted that Giraffe were locally extinct until recent re-introductions into southern Angola from Namibia (Kissama Foundation 2015, East 1999, P. Vaz Pinto pers. comm.). BOTSWANA Current range in Botswana Recent genetic analyses have revealed that the population of Giraffe in the Central Kalahari and Khutse Game Reserves in central Botswana is from the subspecies G. -

Zambezi After Breakfast, We Follow the Route of the Okavango River Into the Zambezi Where Applicable, 24Hrs Medical Evacuation Insurance Region

SOAN-CZ | Windhoek to Kasane | Scheduled Guided Tour Day 1 | Tuesday 16 ETOSHA NATIONAL PARK 30 Group size Oshakati Ondangwa Departing Windhoek we travel north through extensive cattle farming areas GROUP DAY Katima Mulilo and bushland to the Etosha National Park, famous for its vast amount of Classic: 2 - 16 guests per vehicle CLASSIC TOURING SIZE FREESELL Opuwo Rundu Kasane wildlife and unique landscape. In the late afternoon, once we have reached ETOSHA NATIONAL PARK BWABWATA NATIONAL our camp located on the outside of the National Park, we have the rest of the PARK Departure details Tsumeb day at leisure. Outjo Overnight at Mokuti Etosha Lodge. Language: Bilingual - German and English Otavi Departure Days: Otjiwarongo Day 2 | Wednesday Tour Language: Bilingual DAMARALAND ETOSHA NATIONAL PARK Okahandja The day is devoted purely to the abundant wildlife found in the Etosha Departure days: TUESDAYS National Park, which surrounds a parched salt desert known as the Etosha Gobabis November 17 Pan. The park is home to 4 of the Big Five - elephant, lion, leopard and rhino. 2020 December 1, 15 WINDHOEK Swakopmund Game viewing in the park is primarily focussed around the waterholes, some January 19 of which are spring-fed and some supplied from a borehole, ideal places to February 16 Walvis Bay Rehoboth sit and watch over 114 different game species, or for an avid birder, more than March 2,16,30 340 bird species. An extensive network of roads links the over 30 water holes April 13 SOSSUSVLEI Mariental allowing visitors the opportunity of a comprehensive game viewing safari May 11, 25 throughout the park as each different area will provide various encounters. -

National Parks of Namibia.Pdf

Namibia’s National Parks “Our national parks are one of Namibia’s most valuable assets. They are our national treasures and their tourism potential should be harnessed for the benefi t of all people.” His Excellency Hifi kepunye Pohamba Republic of Namibia President of the Republic of Namibia Ministry of Environment and Tourism Exploring Namibia’s natural treasures Sparsely populated and covering a vast area of 823 680 km2, roughly three times the size of the United King- dom, Namibia is unquestionably one of Africa’s premier nature tourism destinations. There is also no doubt that the Ministry of Environment and Tourism is custodian to some of the biggest, oldest and most spectacular parks on our planet. Despite being the most arid country in sub-Saharan Af- rica, the range of habitats is incredibly diverse. Visitors can expect to encounter coastal lagoons dense with flamingos, towering sand-dunes, and volcanic plains carpeted with spring flowers, thick forests teeming with seasonal elephant herds up to 1 000 strong and lush sub-tropical wetlands that are home to crocodile, hippopotami and buffalo. The national protected area network of the Ministry of Environment and Tourism covers 140 394 km2, 17 per cent of the country, and while the century-old Etosha National and Namib-Naukluft parks are deservedly re- garded as the flagships of Namibia’s conservation suc- cess, all the country’s protected areas have something unique to offer. The formidable Waterberg Plateau holds on its summit an ecological ‘lost world’ cut off by geology from its surrounding plains for millennia. The Fish River Canyon is Africa’s grandest, second in size only to the American Grand Canyon. -

7 Day Namibia Highlights – Etosha - Sossusvlei Sossusvlei - Swakopmund - Etosha National Park - Windhoek 7 Days / 6 Nights Minimum: 2 Pax Maximum: 18 Pax

Page | 1 7 Day Namibia Highlights – Etosha - Sossusvlei Sossusvlei - Swakopmund - Etosha National Park - Windhoek 7 Days / 6 Nights Minimum: 2 Pax Maximum: 18 Pax TOUR OVERVIEW Start Accommodation Destination Basis Room Type Duration Day 1 Sossusvlei Lodge or similar Sossusvlei D,B&B 1x Standard Twin 2 Nights Room Day 3 Swakopmund Sands Hotel Swakopmund B&B 1x Standard Twin 2 Nights Room Day 5 Okaukuejo Resort Etosha South D,B&B 1x Standard Twin 1 Night Room Day 6 Namutoni Resort Etosha East D,B&B 1x Standard Twin 1 Night Room MEERCAT SAFARIS VAT # 778169-01-1 [email protected] Katatura, Windhoek REG # CC/2016/01956 +264 81 329 5790 / 85 662 6014 NTB # TSO 01180 Page | 2 Key B&B: Bed and Breakfast D,B&B: Dinner, Bed and Breakfast Price 01 November 2021- 30 June 2022 N$24 300.00 per person sharing N$ 6 790.00 single supplement 01 July 2022 – 30 October 2022 N$25 420.00 per person sharing N$ 8 980.00 single supplement Included 1. Pick up from Windhoek accommodation 2. Standard Information package 3. Professional English speaking tour guide 4. Accommodation as per itinerary 5. Meals as per itinerary 6. Activities as per itinerary 7. Drop off at Windhoek accommodation Excluded 1. Beverages (Alcoholic, soft drinks & bottled water) 2. Other meals not specified 3. Personal Travel insurance 4. Other optional activities 5. Tour guide tips and gratuities 6. Visa’s 7. Flights 8. Items of personal nature Day 1: Sossusvlei Lodge, Sossusvlei MEERCAT SAFARIS VAT # 778169-01-1 [email protected] Katatura, Windhoek REG # CC/2016/01956 +264 81 329 5790 / 85 662 6014 NTB # TSO 01180 Page | 3 Located in southwestern Africa, Namibia boasts a well-developed infrastructure, some of the best tourist facilities in Africa, and an impressive list of breathtaking natural wonders. -

Basingstoke Local Group

BBAASSIINNGGSSTTOOKKEE LLOOCCAALL GGRROOUUPP DECEMBER 2015 NEWSLETTER http://www.rspb.org.uk/groups/basingstoke Contents: From The Group Leader Notices What’s Happening? December’s Outdoor Meeting January’s Outdoor Meeting November’s Outdoor Meeting Namibia: To Hobatere For Mountain Zebras, Mountain Squirrels … And… “Mountain Giraffes”? Local Wildlife News Quiz Page And Finally! Charity registered in England and Wales no. 207076 From The Group Leader Welcome to the December, dare I say Christmas Newsletter! Now that the winter's truly with us, as those attending recent walks will attest to, it's surely time to once again look forward to the coming year, the meetings to attend, the wildlife to look for and enjoy, both within the presentations and out in the field, and all that the RSPB and Britain can offer. We're all very fortunate in that we live in the latter and that we have the former protecting so many areas, with our help, for wildlife, both for now and, hopefully, the future. Hopefully, once again, we'll all get the opportunity to make the most of the special sites under the protection of the Society, some of which the Local Group will be visiting, both locally and further afield on forays to Norfolk etc. in the coming year. Yet again earlier this year the Local Group placed a donation with the HQ to help with work on these sites, so if you do visit any of the c.200 reserves please do remember that your generosity continues to help maintain these, and of course the wildlife that flourishes on them; perhaps you paid for those reeds that the ‘pinging’ Bearded Tit you’re trying to watch are remaining all too elusive in! At the AGM earlier this year the Treasurer, Gerry, explained about changes that we thought ought to be brought in with regard to the annual donation, primarily the way in which such monies would be raised in the future. -

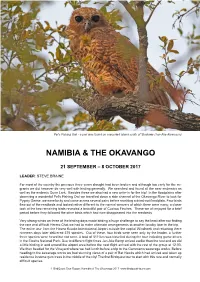

Namibia & the Okavango

Pel’s Fishing Owl - a pair was found on a wooded island south of Shakawe (Jan-Ake Alvarsson) NAMIBIA & THE OKAVANGO 21 SEPTEMBER – 8 OCTOBER 2017 LEADER: STEVE BRAINE For most of the country the previous three years drought had been broken and although too early for the mi- grants we did however do very well with birding generally. We searched and found all the near endemics as well as the endemic Dune Lark. Besides these we also had a new write-in for the trip! In the floodplains after observing a wonderful Pel’s Fishing Owl we travelled down a side channel of the Okavango River to look for Pygmy Geese, we were lucky and came across several pairs before reaching a dried-out floodplain. Four birds flew out of the reedbeds and looked rather different to the normal weavers of which there were many, a closer look at the two remaining birds revealed a beautiful pair of Cuckoo Finches. These we all enjoyed for a brief period before they followed the other birds which had now disappeared into the reedbeds. Very strong winds on three of the birding days made birding a huge challenge to say the least after not finding the rare and difficult Herero Chat we had to make alternate arrangements at another locality later in the trip. The entire tour from the Hosea Kutako International Airport outside the capital Windhoek and returning there nineteen days later delivered 375 species. Out of these, four birds were seen only by the leader, a further three species were heard but not seen. -

05 Night Namib Desert & Etosha National Park

05 NIGHT NAMIB DESERT & ETOSHA NATIONAL PARK This tour is for those who want to experience two of Namibia´s main attractions in the shortest possible time – The Namib Desert and the Etosha National Park. INFORMATION Sossusvlei Located in the scenic Namib-Naukluft National Park, Sossusvlei is where you will find the iconic red sand dunes of the Namib. The clear blue skies contrast with the giant red dunes to make this one of the most scenic natural wonders of Africa and a photographer's heaven. This awe-inspiring destination is possibly Namibia's premier attraction, with its unique dunes rising to almost 400 metres- some of the highest in the world. These iconic dunes come alive in morning and evening light and draw photography enthusiasts from around the globe. Sossusvlei is home to a variety desert wildlife including oryx, springbok, ostrich and a variety of reptiles. Visitors can climb 'Big Daddy', one of Sossusvlei’s tallest dunes; explore Deadvlei, a white, salt, claypan dotted with ancient trees; or for the more extravagant, scenic flights and hot air ballooning are on offer, followed by a once-in-a-lifetime champagne breakfast amidst these majestic dunes. Namib-Naukluft National Park Stretching almost 50000 square kilometres across the red-orange sands of the Namib Desert over the Naukluft Mountains to the east, the Namib-Naukluft National Park is Africa’s biggest wildlife reserve and the fourth largest in the world. Despite the unforgiving conditions, it is inhabited by a plethora of desert-adapted animals, including reptiles, buck, hyenas, jackals, insects and a variety of bird species. -

The Mayflies (Ephemeroptera) of Angola—New Species and Distribution Records from Previously Unchartered Waters, with a Provisional Species Checklist

Zoosymposia 16: 124–138 (2019) ISSN 1178-9905 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zs/ ZOOSYMPOSIA Copyright © 2019 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1178-9913 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zoosymposia.16.1.11 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:EEC14B5A-21DE-4FB7-8D62-AD29C65F35BA The Mayflies (Ephemeroptera) of Angola—new species and distribution records from previously unchartered waters, with a provisional species checklist HELEN M. BARBER-JAMES1,2,3*& INA S. FERREIRA2,1,3 1 Department of Freshwater Invertebrates, Albany Museum, Somerset Street, Makhanda (Grahamstown) 6139, South Africa. 2 Department of Zoology and Entomology, Rhodes University, Makhanda (Grahamstown) 6140, South Africa. 3 National Geographic Okavango Wilderness Project, Wild Bird Trust, South Africa. (*) Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract A preliminary assessment of Ephemeroptera species diversity in Angolan freshwater ecosystems is presented. The results are based on three surveys carried out between 2016 and 2018, supplemented by literature synthesis. The area studied includes headwater streams and tributaries feeding the Okavango Delta, namely the Cubango, Cuito and Cuanavale Rivers, which together produced 35 species, and those flowing into the Zambezi River system, the Cuembo, Cuando, Luanginga and Lungué-Bungo Rivers which together produced 29 species. Twenty-one species were identified from the Cubango River, a fast flowing, rocky substrate river, different in character to all the other rivers surveyed. The other rivers, which all flow over Kalahari sand substrate with dense rooted aquatic macrophytes, generally lacking rocky substrate, produced 33 species between them. Prior to this research, only one mayfly species had been described from Angola in 1959. -

Namibia and Angola: Analysis of a Symbiotic Relationship Hidipo Hamutenya*

Namibia and Angola: Analysis of a symbiotic relationship Hidipo Hamutenya* Introduction Namibia and Angola have much in common, but, at the same time, they differ greatly. For example, both countries fought colonial oppression and are now independent; however, one went through civil war, while the other had no such experience. Other similarities include the fact that the former military groups (Angola’s Movimiento Popular para la Liberacão de Angola, or MPLA, and Namibia’s South West Africa People’s Organisation, or SWAPO) are now in power in both countries. At one time, the two political movements shared a common ideological platform and lent each other support during their respective liberation struggles. The two countries are also neighbours, with a 1,376-km common border that extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Zambezi River in the west. Families and communities on both sides of the international boundary share resources, communicate, trade and engage in other types of exchange. All these facts point to a relationship between the two countries that goes back many decades, and continues strongly today. What defines this relationship and what are the crucial elements that keep it going? Angola lies on the Atlantic coast of south-western Africa. It is richly endowed with natural resources and measures approximately 1,246,700 km2 in land surface area. Populated with more than 14 million people, Angola was a former Portuguese colony. Portuguese explorers first came to Angola in 1483. Their conquest and exploitation became concrete when Paulo Dias de Novais erected a colonial settlement in Luanda in 1575. -

Namibia and Botswana: the Living Desert to the Okavongo a Tropical Birding Custom Trip

Namibia and Botswana: The Living Desert to the Okavongo A Tropical Birding Custom Trip September 1 - 19, 2009 Guide: Ken Behrens All photos by Ken Behrens unless noted otherwise All photos taken during this trip TOUR SUMMARY Namibia often flies under the radar of world travelers, particularly those from North America, despite being one of the jewels of the African continent. It offers an unprecedented combination of birds, mammals, and scenery. Its vast deserts hold special species like the sand-adapted Dune Lark and remarkable mammals like southern oryx. Rising from the desert is a rugged escarpment, whose crags and valleys shelter a range of endemics, from Herero Chat and Hartlaub’s Francolin to black mongoose. In the north lies Etosha National Park, one of Africa’s most renowned protected areas. Here, mammals can be seen in incredible concentrations, particularly towards the end of the dry season, and this park’s waterholes are one of the great spectacles to be seen on the continent. Though less obvious than the mammalian megafauna, Etosha’s birds are also spectacular, with a full range of Kalahari endemics on offer. As you travel north and east, towards the Caprivi Strip, you enter an entirely different world of water, papyrus, and broadleaf woodland. Here, hippos soak in the murky water below cliffs teeming with thousands of nesting Southern Carmine Bee-eaters. The Okavango is another of the world’s great wild places, and it seems extraordinary to experience it after walking amidst towering sand dunes just a few days before. Impala drinking at one of Etosha’s amazing waterholes. -

Namibia Is a Country of Astonishing Contrasts, Home to the Oldest Desert

Namibia is a country of astonishing contrasts, home to the oldest desert on the planet, the white saltpans of Etosha National Park, the uninhabited beaches of the Skeleton Coast and the vast wilderness of Kaokoveld. These unique landscapes are not only home to an astonishing diversity of wildlife, but also to endemic and special wildlife that are found nowhere else on Earth. There are approximately 4 000 species of plants, over 650 bird species and 80 large mammal species. The landscape is defined by an arid, harsh climate and a long geographical history. The western part of the country has a mixture of enormous sand dunes, open plains, rugged valleys, escarpments and mountains and it is here that the oldest desert on the planet, the Namib, is found. The eastern interior is a sand-covered, more uniform landscape and contains the country's second great desert: the Kalahari, a vast and sparsely vegetated savannah that sprawls across the border into South Africa and Botswana. The flat vastness of Namibia's deserts is relieved by a belt of broken mountains and inselbergs (the highest is the Brandberg at 2 579 m / 8 461 feet above sea level), deep dry river valleys that serve as linear oases, savannah and woodlands, and long stretches of sandy beaches along the dramatic Skeleton Coast. All this is in contrast to the rich grasslands, and subtropical woodlands of the Caprivi area in the north- east, the mopane woodlands of Etosha National Park, and the rich coastal lagoons of the Atlantic Ocean on the western coastline. Namibia’s maze of national parks, reserves and community conservancies makes up an impressive 20% of the country, providing many pristine areas for unrivalled wildlife observation.