MARTIAL EAGLE | Polemaetus Bellicosus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Angolan Giraffe (Giraffa Camelopardalis Ssp

Angolan Giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis ssp. angolensis) Appendix 1: Historical and recent geographic range and population of Angolan Giraffe G. c. angolensis Geographic Range ANGOLA Historical range in Angola Giraffe formerly occurred in the mopane and acacia savannas of southern Angola (East 1999). According to Crawford-Cabral and Verissimo (2005), the historic distribution of the species presented a discontinuous range with two, reputedly separated, populations. The western-most population extended from the upper course of the Curoca River through Otchinjau to the banks of the Kunene (synonymous Cunene) River, and through Cuamato and the Mupa area further north (Crawford-Cabral and Verissimo 2005, Dagg 1962). The intention of protecting this western population of G. c. angolensis, led to the proclamation of Mupa National Park (Crawford-Cabral and Verissimo 2005, P. Vaz Pinto pers. comm.). The eastern population occurred between the Cuito and Cuando Rivers, with larger numbers of records from the southeast corner of the former Mucusso Game Reserve (Crawford-Cabral and Verissimo 2005, Dagg 1962). By the late 1990s Giraffe were assumed to be extinct in Angola (East 1999). According to Kuedikuenda and Xavier (2009), a small population of Angolan Giraffe may still occur in Mupa National Park; however, no census data exist to substantiate this claim. As the Park was ravaged by poachers and refugees, it was generally accepted that Giraffe were locally extinct until recent re-introductions into southern Angola from Namibia (Kissama Foundation 2015, East 1999, P. Vaz Pinto pers. comm.). BOTSWANA Current range in Botswana Recent genetic analyses have revealed that the population of Giraffe in the Central Kalahari and Khutse Game Reserves in central Botswana is from the subspecies G. -

WILDLIFE JOURNAL SINGITA GRUMETI, TANZANIA for the Month of April, Two Thousand and Nineteen

Photo by George Tolchard WILDLIFE JOURNAL SINGITA GRUMETI, TANZANIA For the month of April, Two Thousand and Nineteen Temperature Rainfall Recorded Sunrise & Sunset Average minimum: 19°C Faru Faru 47 mm Sunrise 06:40 Average maximum: 29°C Sabora 53 mm Sunset 18:40 Minimum recorded: 17°C Sasakwa 162 mm Maximum recorded: 34.3°C April has been another lovely month, packed full of exciting moments and incredible wildlife viewing. April is usually an incredibly wet month for us here in northern Tanzania, however this year we have definitely received less rain than in years gone by. Only at the end of the month have we seen a noticeable change in the weather and experienced our first heavy downpours. Thankfully there seems to have been just enough to keep the grasses looking green and although the heavy rains have arrived late, an encouraging green flush is spreading across the grasslands. Resident herds of topi, zebra, buffalo, Thompson’s gazelle, eland, Grant’s gazelle and impala are flourishing as usual and have remained as a great presence especially out on the Nyati Plain and the Nyasirori high ground. Reports of the migratory wildebeest were received towards the end of the month, and on the 27th we glanced from the top of Sasakwa Hill to see mega-herds of wildebeest, to the south of our border with the National Park, streaming onto the grasslands at the base of the Simiti Hills. We sit in anticipation and wonder where the great herds will move next. Cat sightings have been great this month, again, despite the long seeding grasses. -

Eagle Hill, Kenya: Changes Over 60 Years

Scopus 34: 24–30, January 2015 Eagle Hill, Kenya: changes over 60 years Simon Thomsett Summary Eagle Hill, the study site of the late Leslie Brown, was first surveyed over 60 years ago in 1948. The demise of its eagle population was near-complete less than 50 years later, but significantly, the majority of these losses occurred in the space of a few years in the late 1970s. Unfortunately, human densities and land use changes are poor- ly known, and thus poor correlation can be made between that and eagle declines. Tolerant local attitudes and land use practices certainly played a significant role in protecting the eagles while human populations began to grow. But at a certain point it would seem that changed human attitudes and population density quickly tipped the balance against eagles. Introduction Raptors are useful in qualifying habitat and biodiversity health as they occupy high trophic levels (Sergio et al. 2005), and changes in their density reflect changes in the trophic levels that support them. In Africa, we know that raptors occur in greater diversity and abundance in protected areas such as the Matapos Hills, Zimbabwe (Macdonald & Gargett 1984; Hartley 1993, 1996, 2002 a & b), and Sabi Sand Reserve, South Africa (Simmons 1994). Although critically important, few draw a direct cor- relation between human effects on the environment and raptor diversity and density. The variables to consider are numerous and the conclusions unworkable due to dif- ferent holding-capacities, latitude, land fertility, seasonality, human attitudes, and different tolerances among raptor species to human disturbance. Although the concept of environmental effects caused by humans leading to rap- tor decline is attractive and is used to justify raptor conservation, there is a need for caution in qualifying habitat ‘health’ in association with the quantity of its raptor community. -

A Multi-Gene Phylogeny of Aquiline Eagles (Aves: Accipitriformes) Reveals Extensive Paraphyly at the Genus Level

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com MOLECULAR SCIENCE•NCE /W\/Q^DIRI DIRECT® PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION ELSEVIER Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 35 (2005) 147-164 www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev A multi-gene phylogeny of aquiline eagles (Aves: Accipitriformes) reveals extensive paraphyly at the genus level Andreas J. Helbig'^*, Annett Kocum'^, Ingrid Seibold^, Michael J. Braun^ '^ Institute of Zoology, University of Greifswald, Vogelwarte Hiddensee, D-18565 Kloster, Germany Department of Zoology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, 4210 Silver Hill Rd., Suitland, MD 20746, USA Received 19 March 2004; revised 21 September 2004 Available online 24 December 2004 Abstract The phylogeny of the tribe Aquilini (eagles with fully feathered tarsi) was investigated using 4.2 kb of DNA sequence of one mito- chondrial (cyt b) and three nuclear loci (RAG-1 coding region, LDH intron 3, and adenylate-kinase intron 5). Phylogenetic signal was highly congruent and complementary between mtDNA and nuclear genes. In addition to single-nucleotide variation, shared deletions in nuclear introns supported one basal and two peripheral clades within the Aquilini. Monophyly of the Aquilini relative to other birds of prey was confirmed. However, all polytypic genera within the tribe, Spizaetus, Aquila, Hieraaetus, turned out to be non-monophyletic. Old World Spizaetus and Stephanoaetus together appear to be the sister group of the rest of the Aquilini. Spiza- stur melanoleucus and Oroaetus isidori axe nested among the New World Spizaetus species and should be merged with that genus. The Old World 'Spizaetus' species should be assigned to the genus Nisaetus (Hodgson, 1836). The sister species of the two spotted eagles (Aquila clanga and Aquila pomarina) is the African Long-crested Eagle (Lophaetus occipitalis). -

South Africa: Magoebaskloof and Kruger National Park Custom Tour Trip Report

SOUTH AFRICA: MAGOEBASKLOOF AND KRUGER NATIONAL PARK CUSTOM TOUR TRIP REPORT 24 February – 2 March 2019 By Jason Boyce This Verreaux’s Eagle-Owl showed nicely one late afternoon, puffing up his throat and neck when calling www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | TRIP REPORT South Africa: Magoebaskloof and Kruger National Park February 2019 Overview It’s common knowledge that South Africa has very much to offer as a birding destination, and the memory of this trip echoes those sentiments. With an itinerary set in one of South Africa’s premier birding provinces, the Limpopo Province, we were getting ready for a birding extravaganza. The forests of Magoebaskloof would be our first stop, spending a day and a half in the area and targeting forest special after forest special as well as tricky range-restricted species such as Short-clawed Lark and Gurney’s Sugarbird. Afterwards we would descend the eastern escarpment and head into Kruger National Park, where we would make our way to the northern sections. These included Punda Maria, Pafuri, and the Makuleke Concession – a mouthwatering birding itinerary that was sure to deliver. A pair of Woodland Kingfishers in the fever tree forest along the Limpopo River Detailed Report Day 1, 24th February 2019 – Transfer to Magoebaskloof We set out from Johannesburg after breakfast on a clear Sunday morning. The drive to Polokwane took us just over three hours. A number of birds along the way started our trip list; these included Hadada Ibis, Yellow-billed Kite, Southern Black Flycatcher, Village Weaver, and a few brilliant European Bee-eaters. -

The Martial Eagle Terror of the African Bush

SCOOP! 4 THE MARTIAL EAGLE TERROR OF THE AFRICAN BUSH The martial eagle is a A CLOSE ENCOUNTER WITH A NEAR-LEGENDARY very large eagle. In total AND SEVERELY THREATENED PREDATOR length, it can range from 78 to 96 cm (31 to 38 in), with a wingspan from 188 to 260 cm (6 ft 2 in to 8 ft 6 in). 5 The martial eagle is one of the world's most powerful avian predators. Prey may vary considerably in size but for the most part, prey weighing less than 0.5 kg (1.1 lb) are ignored, with the average size of prey being between 1 and 5 kg (2.2 and 11.0 lb). TEXT BY ANDREA FERRARI PHOTOS BY ANDREA & ANTONELLA FERRARI uring a lifetime of explorations we have met and mammals, large birds and reptiles. An inhabitant of occasion - while it was gorging itself on a fresh duck or photographed the huge, intimidating martial eagle wooded belts of otherwise open savanna, this species has goose kill by a waterhole in Etosha NP, Namibia - was PolemaetusD bellicosus quite a few times - despite being sadly shown a precipitous decline in the last few centuries rather special. Luckily most martial eagles don’t seem too currently severely threatened and not really common due to a variety of factors as it is one of the most persecuted shy when feasting (if properly approached, of course - we anywhere, it still is relatively easy observing one in the bird species in the world. Due to its habit of taking livestock had already photographed another eating a mongoose in African plains. -

Zambezi After Breakfast, We Follow the Route of the Okavango River Into the Zambezi Where Applicable, 24Hrs Medical Evacuation Insurance Region

SOAN-CZ | Windhoek to Kasane | Scheduled Guided Tour Day 1 | Tuesday 16 ETOSHA NATIONAL PARK 30 Group size Oshakati Ondangwa Departing Windhoek we travel north through extensive cattle farming areas GROUP DAY Katima Mulilo and bushland to the Etosha National Park, famous for its vast amount of Classic: 2 - 16 guests per vehicle CLASSIC TOURING SIZE FREESELL Opuwo Rundu Kasane wildlife and unique landscape. In the late afternoon, once we have reached ETOSHA NATIONAL PARK BWABWATA NATIONAL our camp located on the outside of the National Park, we have the rest of the PARK Departure details Tsumeb day at leisure. Outjo Overnight at Mokuti Etosha Lodge. Language: Bilingual - German and English Otavi Departure Days: Otjiwarongo Day 2 | Wednesday Tour Language: Bilingual DAMARALAND ETOSHA NATIONAL PARK Okahandja The day is devoted purely to the abundant wildlife found in the Etosha Departure days: TUESDAYS National Park, which surrounds a parched salt desert known as the Etosha Gobabis November 17 Pan. The park is home to 4 of the Big Five - elephant, lion, leopard and rhino. 2020 December 1, 15 WINDHOEK Swakopmund Game viewing in the park is primarily focussed around the waterholes, some January 19 of which are spring-fed and some supplied from a borehole, ideal places to February 16 Walvis Bay Rehoboth sit and watch over 114 different game species, or for an avid birder, more than March 2,16,30 340 bird species. An extensive network of roads links the over 30 water holes April 13 SOSSUSVLEI Mariental allowing visitors the opportunity of a comprehensive game viewing safari May 11, 25 throughout the park as each different area will provide various encounters. -

National Parks of Namibia.Pdf

Namibia’s National Parks “Our national parks are one of Namibia’s most valuable assets. They are our national treasures and their tourism potential should be harnessed for the benefi t of all people.” His Excellency Hifi kepunye Pohamba Republic of Namibia President of the Republic of Namibia Ministry of Environment and Tourism Exploring Namibia’s natural treasures Sparsely populated and covering a vast area of 823 680 km2, roughly three times the size of the United King- dom, Namibia is unquestionably one of Africa’s premier nature tourism destinations. There is also no doubt that the Ministry of Environment and Tourism is custodian to some of the biggest, oldest and most spectacular parks on our planet. Despite being the most arid country in sub-Saharan Af- rica, the range of habitats is incredibly diverse. Visitors can expect to encounter coastal lagoons dense with flamingos, towering sand-dunes, and volcanic plains carpeted with spring flowers, thick forests teeming with seasonal elephant herds up to 1 000 strong and lush sub-tropical wetlands that are home to crocodile, hippopotami and buffalo. The national protected area network of the Ministry of Environment and Tourism covers 140 394 km2, 17 per cent of the country, and while the century-old Etosha National and Namib-Naukluft parks are deservedly re- garded as the flagships of Namibia’s conservation suc- cess, all the country’s protected areas have something unique to offer. The formidable Waterberg Plateau holds on its summit an ecological ‘lost world’ cut off by geology from its surrounding plains for millennia. The Fish River Canyon is Africa’s grandest, second in size only to the American Grand Canyon. -

7 Day Namibia Highlights – Etosha - Sossusvlei Sossusvlei - Swakopmund - Etosha National Park - Windhoek 7 Days / 6 Nights Minimum: 2 Pax Maximum: 18 Pax

Page | 1 7 Day Namibia Highlights – Etosha - Sossusvlei Sossusvlei - Swakopmund - Etosha National Park - Windhoek 7 Days / 6 Nights Minimum: 2 Pax Maximum: 18 Pax TOUR OVERVIEW Start Accommodation Destination Basis Room Type Duration Day 1 Sossusvlei Lodge or similar Sossusvlei D,B&B 1x Standard Twin 2 Nights Room Day 3 Swakopmund Sands Hotel Swakopmund B&B 1x Standard Twin 2 Nights Room Day 5 Okaukuejo Resort Etosha South D,B&B 1x Standard Twin 1 Night Room Day 6 Namutoni Resort Etosha East D,B&B 1x Standard Twin 1 Night Room MEERCAT SAFARIS VAT # 778169-01-1 [email protected] Katatura, Windhoek REG # CC/2016/01956 +264 81 329 5790 / 85 662 6014 NTB # TSO 01180 Page | 2 Key B&B: Bed and Breakfast D,B&B: Dinner, Bed and Breakfast Price 01 November 2021- 30 June 2022 N$24 300.00 per person sharing N$ 6 790.00 single supplement 01 July 2022 – 30 October 2022 N$25 420.00 per person sharing N$ 8 980.00 single supplement Included 1. Pick up from Windhoek accommodation 2. Standard Information package 3. Professional English speaking tour guide 4. Accommodation as per itinerary 5. Meals as per itinerary 6. Activities as per itinerary 7. Drop off at Windhoek accommodation Excluded 1. Beverages (Alcoholic, soft drinks & bottled water) 2. Other meals not specified 3. Personal Travel insurance 4. Other optional activities 5. Tour guide tips and gratuities 6. Visa’s 7. Flights 8. Items of personal nature Day 1: Sossusvlei Lodge, Sossusvlei MEERCAT SAFARIS VAT # 778169-01-1 [email protected] Katatura, Windhoek REG # CC/2016/01956 +264 81 329 5790 / 85 662 6014 NTB # TSO 01180 Page | 3 Located in southwestern Africa, Namibia boasts a well-developed infrastructure, some of the best tourist facilities in Africa, and an impressive list of breathtaking natural wonders. -

Basingstoke Local Group

BBAASSIINNGGSSTTOOKKEE LLOOCCAALL GGRROOUUPP DECEMBER 2015 NEWSLETTER http://www.rspb.org.uk/groups/basingstoke Contents: From The Group Leader Notices What’s Happening? December’s Outdoor Meeting January’s Outdoor Meeting November’s Outdoor Meeting Namibia: To Hobatere For Mountain Zebras, Mountain Squirrels … And… “Mountain Giraffes”? Local Wildlife News Quiz Page And Finally! Charity registered in England and Wales no. 207076 From The Group Leader Welcome to the December, dare I say Christmas Newsletter! Now that the winter's truly with us, as those attending recent walks will attest to, it's surely time to once again look forward to the coming year, the meetings to attend, the wildlife to look for and enjoy, both within the presentations and out in the field, and all that the RSPB and Britain can offer. We're all very fortunate in that we live in the latter and that we have the former protecting so many areas, with our help, for wildlife, both for now and, hopefully, the future. Hopefully, once again, we'll all get the opportunity to make the most of the special sites under the protection of the Society, some of which the Local Group will be visiting, both locally and further afield on forays to Norfolk etc. in the coming year. Yet again earlier this year the Local Group placed a donation with the HQ to help with work on these sites, so if you do visit any of the c.200 reserves please do remember that your generosity continues to help maintain these, and of course the wildlife that flourishes on them; perhaps you paid for those reeds that the ‘pinging’ Bearded Tit you’re trying to watch are remaining all too elusive in! At the AGM earlier this year the Treasurer, Gerry, explained about changes that we thought ought to be brought in with regard to the annual donation, primarily the way in which such monies would be raised in the future. -

Namibia & the Okavango

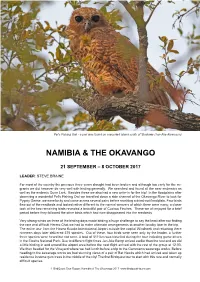

Pel’s Fishing Owl - a pair was found on a wooded island south of Shakawe (Jan-Ake Alvarsson) NAMIBIA & THE OKAVANGO 21 SEPTEMBER – 8 OCTOBER 2017 LEADER: STEVE BRAINE For most of the country the previous three years drought had been broken and although too early for the mi- grants we did however do very well with birding generally. We searched and found all the near endemics as well as the endemic Dune Lark. Besides these we also had a new write-in for the trip! In the floodplains after observing a wonderful Pel’s Fishing Owl we travelled down a side channel of the Okavango River to look for Pygmy Geese, we were lucky and came across several pairs before reaching a dried-out floodplain. Four birds flew out of the reedbeds and looked rather different to the normal weavers of which there were many, a closer look at the two remaining birds revealed a beautiful pair of Cuckoo Finches. These we all enjoyed for a brief period before they followed the other birds which had now disappeared into the reedbeds. Very strong winds on three of the birding days made birding a huge challenge to say the least after not finding the rare and difficult Herero Chat we had to make alternate arrangements at another locality later in the trip. The entire tour from the Hosea Kutako International Airport outside the capital Windhoek and returning there nineteen days later delivered 375 species. Out of these, four birds were seen only by the leader, a further three species were heard but not seen. -

05 Night Namib Desert & Etosha National Park

05 NIGHT NAMIB DESERT & ETOSHA NATIONAL PARK This tour is for those who want to experience two of Namibia´s main attractions in the shortest possible time – The Namib Desert and the Etosha National Park. INFORMATION Sossusvlei Located in the scenic Namib-Naukluft National Park, Sossusvlei is where you will find the iconic red sand dunes of the Namib. The clear blue skies contrast with the giant red dunes to make this one of the most scenic natural wonders of Africa and a photographer's heaven. This awe-inspiring destination is possibly Namibia's premier attraction, with its unique dunes rising to almost 400 metres- some of the highest in the world. These iconic dunes come alive in morning and evening light and draw photography enthusiasts from around the globe. Sossusvlei is home to a variety desert wildlife including oryx, springbok, ostrich and a variety of reptiles. Visitors can climb 'Big Daddy', one of Sossusvlei’s tallest dunes; explore Deadvlei, a white, salt, claypan dotted with ancient trees; or for the more extravagant, scenic flights and hot air ballooning are on offer, followed by a once-in-a-lifetime champagne breakfast amidst these majestic dunes. Namib-Naukluft National Park Stretching almost 50000 square kilometres across the red-orange sands of the Namib Desert over the Naukluft Mountains to the east, the Namib-Naukluft National Park is Africa’s biggest wildlife reserve and the fourth largest in the world. Despite the unforgiving conditions, it is inhabited by a plethora of desert-adapted animals, including reptiles, buck, hyenas, jackals, insects and a variety of bird species.