Chapter I Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur

A STUDY ON HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATION OF TANGKHUL COMMUNITY IN UKHRUL DISTRICT, MANIPUR. A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPEETH, PUNE FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN SOCIAL WORK UNDER THE BOARD OF SOCIAL WORK STUDIES BY DEPEND KAZINGMEI PRN. 15514002238 UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF DR. G. R. RATHOD DIRECTOR, SOCIAL SCIENCE CENTRE, BVDU, PUNE SEPTEMBER 2019 DECLARATION I, DEPEND KAZINGMEI, declare that the Ph.D thesis entitled “A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur.” is the original research work carried by me under the guidance of Dr. G.R. Rathod, Director of Social Science Centre, Bharati Vidyapeeth University, Pune, for the award of Ph.D degree in Social Work of the Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune. I hereby declare that the said research work has not submitted previously for the award of any Degree or Diploma in any other University or Examination body in India or abroad. Place: Pune Mr. Depend Kazingmei Date: Research Student i CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled, “A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur”, which is being submitted herewith for the award of the Degree of Ph.D in Social Work of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune is the result of original research work completed by Mr. Depend Kazingmei under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work incorporated in this thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any Degree or similar title of this or any other University or examining body. -

The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy

THE IMPACT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE ON TANGKHUL LITERACY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPEETH, PUNE FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) IN ENGLISH BY ROBERT SHIMRAY UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF Dr. GAUTAMI PAWAR UNDER THE BOARD OF ARTS & FINEARTS STUDIES MARCH, 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the thesis entitled “The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy” completed by me has not previously been formed as the basis for the award of any Degree or other similar title upon me of this or any other Vidyapeeth or examining body. Place: Robert Shimray Date: (Research Student) I CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled “The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy” which is being submitted herewith for the award of the degree of Vidyavachaspati (Ph.D.) in English of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune is the result of original research work completed by Robert Shimray under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work incorporated in this thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any Degree or similar title or any University or examining body upon him. Place: Dr. Gautami Pawar Date: (Research Guide) II ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First of all, having answered my prayer, I would like to thank the Almighty God for the privilege and opportunity of enlightening me to do this research work to its completion and accomplishment. Having chosen Rev. William Pettigrew to be His vessel as an ambassador to foreign land, especially to the Tangkhul Naga community, bringing the enlightenment of the ever lasting gospel of love and salvation to mankind, today, though he no longer dwells amongst us, yet his true immortal spirit of love and sacrifice linger. -

9. List of Primary Handloom Cooperative Societies Approved By

LIST OF PRIMARY HANDLOOM COOPERATIVE SOCIETIES APPROVED BY SIMRC ON 28-12-2013 ----- Sl. Name of Society Central State share Total No. share 1 Renu H/L & H/C C.S.Ltd. 1941763.00 215750.00 2157513.00 2 Jaganath Multipurpose Cum W.C.S. Ltd 89389.00 9932.00 99321.00 3 Kakwa Lilando Lampak Emoinu Multi Ind. C.S. Ltd 11412.00 126.00 11538.00 4 Achanbigei Mayai Leikai Imoinu WCS Ltd. 443560.00 49280.00 492840.00 5 Kongpal Kongkham Awang Leikai Muga & Silk W.C.S. Ltd 62273.00 6919.00 69192.00 6 Lingthoingambi Multipurpose Cum W.C .S. Ltd 31928.00 3547.00 35475.00 7 Thambal Khong Maning Leikai Shija W.C.S. Ltd 207852.00 23094.00 230946.00 8 Lourembam Leirak Gobinda Macha W.C.S.Ltd 52101.00 5839.00 57940.00 9 Wangkhei Puja Lampak Mamang Leikai W.C.S. Ltd 68999.00 7666.00 76665.00 10 Dhobi Pukhri Mapal Muga & Silk W.C.S. Ltd. 73076.00 8120.00 81196.00 11 Sairem Handloom production & Exports CS Ltd. 194216.00 21580.00 215796.00 12 Amakcham Pandit Leikai Multi Industrial C.S. Ltd 7734.00 10859.00 18593.00 13 Kongpal Irampham Leikai H/L & H/C C.S Ltd 48398.00 5378.00 53776.00 14 Khabam Mayai Leikai W.C.S. Ltd 124695.00 13854.00 138549.00 15 Ayangleima H/L & H/C C.S. Ltd 46121.00 5124.00 51245.00 16 Wangkhei Leimarol H/L & H/C C.S. Ltd 28071.00 3119.00 31190.00 17 Yaoreishim H/L & H/C C.S. -

GOVT. SCHOOLS Type of School Rural/ Sl

LIST OF SCHOOLS ( As on 30th September, 2015 ) GOVT. SCHOOLS Type of School Rural/ Sl. Class Managemen Name of School Boys/ Address Urban Constituency Block Remarks No. Structure t Girls/ (R/U) Co-Edn 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 HIGHER SECONDARY Schools in CPIS ( ZEO - Bishnupur ) 1 Bishnupur Higher Secondary School VI-XII Edn Dept Co-Edn. Bishnupur Ward No.6 Urban Bishnupur BM Bishnupur Hr./Sec Nambol Hr./Sec, Nambol 2 Nambolg Higherp Secondary p School IX-XII Edn Dept Co-Edn. Nambol Ward No. 3 Urban Nambol NM 3 Higher Secondary School IX-XII Edn Dept Co-Edn. Moirang Lamkhai Urban Moirang MM Moirang Multipurpose Hr./Sec Schools in CPIS ZEO Imphal- East 1 Ananda Singh Hr.Sec. School IX-XII Edn Dept Co-Edn. khumunnom Urban Wangkhei IMC Ananda Singh Hr./Sec Academy 2 Churachand Hr.Sec. School IX-XII Edn Dept Boys Palace Gate Urban Yaiskul IMC C.C. Higher Sec. School 3 Lamlong Hr.Sec. School VI-XII Edn Dept Co-Edn. Khurai Thoudam Lk. Urban Wangkhei IMC Lamlong Hr./Sec 4 Azad Hr.Sec. School VI-XII Edn Dept Co-Edn. Yairipok Tulihal Rural Andro I- E -II Azad High School, Yairipok 5 Sagolmang Hr.Sec. School VI-XII Edn Dept Co-Edn. Sagolmang Rural Khundrakpam I- E -I Sagolmang Govt. H/S. ( ZEO-Jiribam) 1 Jiribam Higher Secondary IX-XII Edn Dept Co-Edn. Babupara Jiribam Urban Jiribam JM Jiribam Hr./Sec 2 Borobekara Hr.Sec. III-XII Edn Dept Co-Edn. Borobekara Rural Jiribam Jiribam Borobekra Hr. -

COVID-19 Pandemic a Warning to Mankind : Experts and Openly Declaring Sup- Held Earlier

JNIMS clarifies Fear, anxiety, apprehension grip Ukhrul as... IMPHAL, Jun 28: The Lockdown to be Jawaharlal Nehru Institute of Medical Sciences (JNIMS) has clarified to the query extended till Jul 15 First report of 25 says negative, second says positive raised by Democratic Stu- Mungchan Zimik lage of Ukhrul. dents Alliance of Manipur Meanwhile the convener (DESAM) that there are 150 UKHRUL, Jun 28 : Fear, of Tangkhul Co-ordination dedicated COVID beds with anxiety and apprehension Forum on COVID-19 bed occupancy of 140 to 150 have gripped Ukhrul district (TCFC -19) K Tuisem tak- per day. after 25 persons who were ing the development "All the daily wastes gen- declared negative after their seriously questioned the per- erated from COVID wards samples were tested were sons (microbiologists) like PPE, caps, face cover, again declared to be positive handling the test lab at shoe cover, gloves, face within a span of 24 hours. RIMS and asserted that they masks, etc are treated with Twenty five persons who should be held accountable sodium hypochlorite solu- were declared negative of for the faulty test result. tion and then collected in the dreaded virus on June 26 In case there is commu- double layered polythene however found that they had nity spread, the persons bags and then burnt in the tested positive on June 27. concerned including the Incinerator Plant," said Dr The samples of the 25 Health Department should Rajen Singh in a statement IMPHAL, Jun 28 (DIPR) persons were collected on be held responsible, he as- on plain paper. June 22 and June 23 and the serted. -

Statistical Year Book of Ukhrul District 2014

GOVERNMENT OF MANIPUR STATISTICAL YEAR BOOK OF UKHRUL DISTRICT 2014 DISTRICT STATISTICAL OFFICE, UKHRUL DIRECTORATE OF ECONOMICS & STATISTICS GOVERNMENT OF MANIPUR PREFACE The present issue of ‘Statistical Year Book of Ukhrul District, 2014’ is the 8th series of the publication earlier entitled „Statistical Abstract of Ukhrul District, 2007‟. It presents the latest available numerical information pertaining to various socio-economic aspects of Ukhrul District. Most of the data presented in this issue are collected from various Government Department/ Offices/Local bodies. The generous co-operation extended by different Departments/Offices/ Statutory bodies in furnishing the required data is gratefully acknowledged. The sincere efforts put in by Shri N. Hongva Shimray, District Statistical Officer and staffs who are directly and indirectly responsible in bringing out the publications are also acknowledged. Suggestions for improvement in the quality and coverage in its future issues of the publication are most welcome. Dated, Imphal Peijonna Kamei The 4th June, 2015 Director of Economics & Statistics Manipur. C O N T E N T S Table Page Item No. No. 1. GENERAL PARTICULARS OF UKHRUL DISTRICT 1 2. AREA AND POPULATION 2.1 Area and Density of Population of Manipur by Districts, 2011 Census. 1 2.2 Population of Manipur by Sector, Sex and Districts according to 2011 2 Census 2.3 District wise Sex Ratio of Manipur according to Population Censuses 2 2.4 Sub-Division-wise Population and Decadal Growth rate of Ukhrul 3 District 2.5 Population of Ukhrul District by Sex 3 2.6 Sub-Division-wise Population in the age group 0-6 of Ukhrul District by sex according to 2011 census 4 2.7 Number of Literates and Literacy Rate by Sex in Ukhrul District 4 2.8 Workers and Non-workers of Ukhrul District by sex, 2001 and 2011 5 censuses 3. -

District Report UKHRUL

Baseline Survey of Minority Concentrated Districts District Report UKHRUL Study Commissioned by Ministry of Minority Affairs Government of India Study Conducted by Omeo Kumar Das Institute of Social Change and Development: Guwahati VIP Road, Upper Hengerabari, Guwahati 781036 1 ommissioned by the Ministry of Minority CAffairs, this Baseline Survey was planned for 90 minority concentrated districts (MCDs) identified by the Government of India across the country, and the Indian Council of Social Science Research (ICSSR), New Delhi coordinates the entire survey. Omeo Kumar Das Institute of Social Change and Development, Guwahati has been assigned to carry out the Survey for four states of the Northeast, namely Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya and Manipur. This report contains the results of the survey for Ukhrul district of Manipur. The help and support received at various stages from the villagers, government officials and all other individuals are most gratefully acknowledged. ■ Omeo Kumar Das Institute of Social Change and Development is an autonomous research institute of the ICSSR, New delhi and Government of Assam. 2 CONTENTS BACKGROUND....................................................................................................................................8 METHODOLOGY.................................................................................................................................9 TOOLS USED ......................................................................................................................................10 -

Review of Research Impact Factor : 5.2331(Uif) Ugc Approved Journal No

Review Of ReseaRch impact factOR : 5.2331(Uif) UGc appROved JOURnal nO. 48514 issn: 2249-894X vOlUme - 7 | issUe - 10 | JUly - 2018 __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATION OF TANGKHUL COMMUNITY IN UKHRUL DISTRICT, MANIPUR STATE Depend Kazingmei Ph. D Scholar , Social Work Department , Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth Pune. ABSTRACT The Tribal communities are the most marginalized group in India as per their disadvantages and exploitation by the outsiders. The peace and harmony of the Tangkhul community are disturbed by continuous violation act committed by various Arm forces and insurgents in the district. It is the responsibility of the government to tackle human rights violation and focus on the grievances faced by the Tangkhul community. Due to implementation of AFSP Act 1958 Manipur state has been suffered under the power of Arm Forces. Many innocent lives have been taken by the Indian Arm forces resulting to increase in widows and orphans. Youth life has been vulnerable and risked due to intense suspect and torture given by the Arm forces. Exploitation towards the Tangkhul community and denial of human rights should not be taken as granted they should be safeguarded equally as Indian citizen. KEY WORDS : National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), Armed Forces Special Powers Act, (AFSPA), Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA), United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and Human Rights Violation. INTRODUCTION Manipur state is one of the eight sister’s state of Northeast India with the total population of about 2.6 million, inhabiting more than 30 indigenous communities with unique multiple culture. Since the implemented of AFSP Act in 1980 at present there are roughly 100,000 Indian armed forces in Manipur not including Manipur state police commando units. -

BOARD of SECONDARY EDUCATION, MANIPUR School-Wise Pass Percentage for H.S.L.C

BOARD OF SECONDARY EDUCATION, MANIPUR School-wise pass percentage for H.S.L.C. Examination, 2019 1-Government Stu. 1st 2nd 3rd Total Sl. No. Code Name of School Pass% App. Div. Div. Div. Passed 1 36091 ABDUL ALI HIGH MADRASSA, LILONG 37 4 19 0 23 62.16 2 28331 AHMEDABAD HIGH SCHOOL, JIRIBAM 48 0 7 3 10 20.83 3 98741 AIMOL CHINGNUNGHUT HIGH SCHOOL, CHANDEL 50 4 19 0 23 46 4 88381 AKHUI HIGH SCHOOL, TAMENGLONG 5 1 4 0 5 100 5 21201 ANANDA SINGH HR. SECONDARY ACADEMY, IMPHAL24 3 7 0 10 41.67 6 29121 ANDRO HIGH SCHOOL, ANDRO IMPHAL EAST DISTRICT9 0 5 1 6 66.67 7 79451 AWANG LONGA KOIRENG GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL, LONGA13 KOIRE 1 2 0 3 23.08 8 21211 AWANG POTSANGBAM HIGH SCHOOL, AWANG POTSANGBAM21 0 2 1 3 14.29 9 21221 AZAD HIGH SCHOOL, YAIRIPOK 84 27 55 0 82 97.62 10 18271 BENGOON HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL, MAYANG IMPHAL30 4 20 4 28 93.33 11 10031 BHAIRODAN MAXWELL HINDI HIGH SCHOOL, IMPHAL19 1 2 1 4 21.05 12 79431 BISHNULAL HIGH SCHOOL, CHARHAJARE 50 8 37 2 47 94 13 43101 BISHNUPUR HIGH SCHOOL , BISHNUPUR 31 7 14 1 22 70.97 14 43111 BISHNUPUR HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL, BISHNUPUR68 0 5 1 6 8.82 15 21231 BOROBEKRA HR. SEC. SCHOOL, JIRIBAM 51 1 11 1 13 25.49 16 63981 BUKPI HIGH SCHOOL, B.P.O. BUKPI, CCPUR 16 0 5 0 5 31.25 17 79221 BUNGTE CHIRU HIGH SCHOOL, SADAR HILLS 7 0 1 0 1 14.29 18 21241 C.C. -

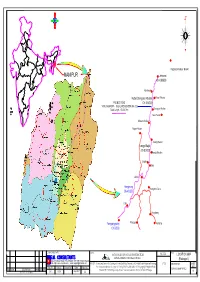

WORK\NHIDCL\Manipur\DRAWING YN UJ SETUP\KEY

L A N D U S E / L A N D C O V E R IMPHAL EAST DISTRICT , MANIPUR ( RESTRICTED CIRCULATION AMONG INTENDED AND AUTHORISED USERS ONLY ) K e Thonamba ith T e lm KeithenmanbiTumnoupokpi an S b i-T ho n a C m b a R 9 o a 3 d - E H N I Matakkhong Heinoupok Makengngularou Bolsang-Kholjang Road M R N o Khoirentampak ln o m - J a Makeng n g m Khonjin Khongjail o T l R o A a d S Kuraopokpi g n P a r i ® o K I 0 1.25 2.5 5 u d Im a S p 800 h # a l - A S D a Puramkhunou ik Kilometers u l R o a d Sadanglonga 807 # T I Puram_Likli aharup Pukhao N Ekpal khunou T I Kanglatongbi A Pukhoahallup Pukhao Khabam Ja mm u & P Khewa Company o K a a d sh h m a k ir o u R P Thongnagpal i Khongban Tangkhul a Ekpalkhullen m k b Himachal Pradesh e A D ja S n S a u g P Chandigarh o lm Sekmai an Haryana d g oa Delhi U R Sin tt Keingamkhunou a S a N m Uyumpok r m i Yumam Patlou P Aarunachal Pradesh n ra g a d in m 968 Rajasthan e e s Sikkim K k # h o 196 I m # S sam As e R k Y o Purumkhulen Nagaland m Meghalaya u a La Tingri E m d mb Bihar a oik Manipur to i n h Kanto an ul K R d N Gujarat g a Tripura o m West Bengal Le a P a a o i Madhya Pradesh im o ra Mizoram d K t a R n s g h k i h b h u S o a Leikinthabi a aretkhul u a T n o P m n n g n m Maharabi S o o g Dadra and Nagar Haveli R u k t u a b e d oa h s u Orissa a a Khurkhul d K S um o n m K Maharashtra t g l i ho H b n b k e R g a a In a K K Tendongyan k u Keibikhulen Laikot m o ro r o a o n Road a M r ei K L donya o mb 812 h e Ten R d ha # ur i l w S uk m o o a sh h a u r e ul Potsangbamkhoiru a R k d a T ad o h -

District Census Handbook, Imphal East, Part-XII a & B, Series-15

CENSUS OF INDIA 2001 SERIES':'15 MANIPUR DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK Part XII - A & B I'MPHAL EAST DISTRICT VILLAGE & TOWN DIRECTORY & VILLAGE AND TOWNVVISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT Y.Thamkishore Singh of the Indian Administrative Service, Director of Census Operations, Manipur Product Code Number ??-???-2CX>1 - Cen-Book (E) DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK: IMPHAL EAST Shree Shree Govindajee Temple This is the temple of Shree Shree Govindajee at the present Palace Compound, in the heart of the Imphal City, on the eastern bank of the Imphal River. The temple is being observed as a sacred religious & worshipping place by the devoted Hindu Manipuri Vaishnavaites. This may be recalled that during the Anglo-Manipuri War in 1891, "Kangla Fort" the original Manipur Maharaja's Palace was destroyed and occupied by the British Garrison. Since then a New Palace with a New Temple at this present existing Palatial Site was constructed in 1907. Shree Shree Govindajee was then resurrected in this New Temple and which was inaugurated in 1910, by His Highness, Shree Shree Yukt Maha raja Sir Churachand Singh, KCSI,CBE . It has three sections that there is the main Idol of Shree Govindajee (Lord Krishna), in the middle, the Idol of Shree Jagannath, (Lord Jagannath) in the north and the Idol of Shree Gouranga Prabhu, in the south. The temple is a place for performance of Manipllri Art and Culture and Cultural Programmes. Im mediately in front of the temple, there is a big Mandop/Jagamahal where various dance sequences depicting the play of Lord Krishna are presented throughout the year in obei sance of the Lord Krishna. -

Roll Numbers Allotted MTS.Xlsx

Annexure to Notification No. AO/252/MTS/2016(5)-DE(S)Pt-1 dated 5/12/2018 Applicant's Roll Numbers in respect of the recruitment of MTS in the Department of Education(S), Manipur. Sl. No. Name of Applicants Residential Address Roll No 1 Chongtham Anup Singh Sagoltongba Makha Leikai 10001 2 Nikhindra Chongtham Sagoltongba Makha Leikai 10002 C/O Upa Thanghrim, Muolvaiphai Phaiveng, 3 Warhnem Sinrung 10003 Po/Ps, Dist-Churachandpur 795128 Chahkap Village, Po/Ps-Chakpikarong, 4 Joseph Seikholet Hanghal 10004 Chandel, Manipur Leilon Khunou Village, Bpo-Leimakhong, Po- 5 Lamkholen Vaiphei 10005 Mantripukhri, Senapati 795002 6 Mideuyile Tousem, Tamenglong, Manipur 795141 10006 Viii- Charhazare, Po- Motbung, Ps- 7 Krishna Kumar Mainali 10007 Gamnom/Sapermeina, Senapati, Manipur 8 Paotinkai Guite New Checkon, Imphal 10008 9 Neihoivah Guite New Checkon, Imphal 10009 Leibi Village, H/N0-79, Po-Pallel, Chandel 10 Dangshawa Koshang 10010 795135 11 Charanga Koshang Maringphai, Po-Pallel Chandel 795135 10011 Chingjaroi Ngachaphung Village Ukhrul, 12 R. Clifford 10012 Manipur 795142, H/No-32 13 Ngoruh Borda Moyon Kurkam Village, Chandel, Manipur 795127 10013 14 Sl. Hatlomkim L. Mulvi P.O. Mantripukhri, 10014 Sangaiprou Behind Fci Godown, Po-Tulihal, 15 Hrangneiyang Kom 10015 Imphal West 795140 Tuisenphai Village, Senapati, Po-Porompat, 16 Moses Shaichal 10016 Ps-Lamlai, Bpo-Takhel 795005 Singda Kuki Village, Po-Lamshang, Bpo- 17 Thangjalal Kipgen 10017 Kharam Vaiphei 795146 Motbung Village, Sadar Hills, Senapati, 18 Lhingneichong Tuboi 10018 Manipur Khangabok Moirang Palli Leikai, Khangabok, 19 Moirangthem Sanjit Singh 10019 Thoubal, Manipur 795138 Yairipok Bishnunaha, Po/Ps-Yairipok, 20 Khangembam Bamkim Singh 10020 Thoubal, Manipur 795149 Tengnoupal Village, Po-Moreh, Ps- 21 Phuthou Shominlen Mate 10021 Tengnoupal, Chandel 795131 Thoubal Khekman Makha Leikai 22 Asem Suran Singh 10022 Wangmataba 23 Ngamkholien Vaiphei Ts.