Cultures in Contact at Colony Ross Kent G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smith Collection of Local Reports & Studies (PDF)

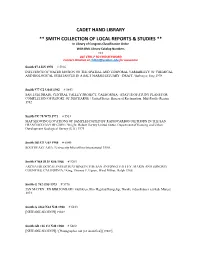

CADET HAND LIBRARY ** SMITH COLLECTION OF LOCAL REPORTS & STUDIES ** In Library of Congress Classification Order With BML Library Catalog Numbers *** USE CTRL-F TO FIND KEYWORD Contact librarian at [email protected] for assistance Smith 87.3 I65 1978 # 5916 INFLUENCE OF WATER MOTION ON THE SPATIAL AND TEMPORAL VARIABILITY OF CHEMICAL AND BIOLOGICAL SUBSTANCES IN A SALT MARSH ESTUARY : DRAFT / Imberger, Jorg 1978. Smith 977 C2 U645 1982 # 5843 SAN LUIS DRAIN, CENTRAL VALLEY PROJECT, CALIFORNIA : STATUS OF STUDY PLANS FOR COMPLETION OF REPORT OF DISCHARGE / United States. Bureau of Reclamation. Mid-Pacific Region 1982. Smith CC 78 W75 1971 # 5513 MAP SHOWING LOCATIONS OF SAMPLES DATED BY RADIOCARBON METHODS IN THE SAN FRANCISCO BAY REGION / Wright, Robert Harvey United States. Department of Housing and Urban Development Geological Survey (U.S.) 1971. Smith DS 521 U65 1980 # 6040 SOUTHEAST ASIA / University Microfilms International 1980. Smith F 868 S135 K56 1966 # 5265 ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS IN THE SAN ANTONIO VALLEY, MARIN AND SONOMA COUNTIES, CALIFORNIA / King, Thomas F. Upson, Ward Milner, Ralph 1966. Smith G 782 G85 1973 # 5776 JAN MAYEN : EN BIBLIOGRAFI / Gulliksen, Elin Hegstad Kongelige Norske videnskabers selskab. Museet 1973. Smith G 4362 N42 N48 1980 # 6233 [NEWARK SLOUGH] 1980?. Smith GB 126 C2 N48 1980 # 5482 [NEWARK SLOUGH] / [Photographer not yet identified] [1980?]. Smith GB 126 C2 S65 1998 # 6267 TOMALES ENVIRONMENT / Smith, Stephen V. Hollibaugh, James T. University of Hawaii. Schooll of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology Tiburon Center for Environmental Studies [1998?]. Smith GB 428 G46 1974 # 6154 GEOLOGY / Environmental Research Consultants (Firm) 1974. Smith GB 451 M35 1960 # 5777 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF COASTAL GEOMORPHOLOGY OF THE WORLD / McGill, John T. -

Bodega Bay Field Trip Guide

ESP/ERS 30 World Ecosystem and Geography Davis-Bodega Bay Sacramento Valley - Coastal Ranges & Valleys - Coastline Introduction This trip follows a westward transect from Davis across the low coastal mountain ranges to the coast. A. Plant Communities 1. Central Valley Grassland (now primarily agricultural fields and orchards) 2. Oak Savannas and Oak Woodlands 3. Chaparral and a chaparral variant with Gray Pine 4. A variety of Riparian habitats 5. Mixed Evergreen Forest 6. Redwood Forest 7. North Coastal Scrub and Prairie 8. Coastal Beach, Marsh, and Tidal Communities B. Environmental Factors Climatic zones you will encounter include the somewhat “continental” climate of the Sacramento Valley, characterized by cool, wet winters with frequent winter fog (a result of cold air subsidence off the Sierras and entrapment in the Valley by the Coast Ranges), and long, dry, hot summers. Even more continental climates are characteristic of regions much further inland, e.g., Ohio. Really extreme continental climates occur in Central Asia and Siberia. Continental climates are so called because as you move inland away from the ocean, the moderating effect of the ocean on temperature leads to more extremes inland. The Coast Ranges are characterized by somewhat less extreme, but still highly variable, conditions of temperature and precipitation as they are in a zone of transition between the more Continental climate of the Valley and the highly Maritime climate of the Coast. The climate along the Coast is dominated by the cool waters of the Pacific Ocean and the California Current which flows south along this part of our coast. The ocean acts as a buffer and greatly reduces the extremes in temperature characteristic of the Sacramento Valley but also increases the amount of moisture in the air, increasing relative humidity. -

Appendix 1. Bodega Marine Lab Student Reports on Polychaete Biology

Appendix 1. Bodega Marine Lab student reports on polychaete biology. Species names in reports were assigned to currently accepted names. Thus, Ackerman (1976) reported Eupolymnia crescentis, which was recorded as Eupolymnia heterobranchia in spreadsheets of current species (spreadsheets 2-5). Ackerman, Peter. 1976. The influence of substrate upon the importance of tentacular regeneration in the terebellid polychaete EUPOLYMNIA CRESCENTIS with reference to another terebellid polychaete NEOAMPHITRITE ROBUSTA in regard to its respiratory response. Student Report, Bodega Marine Lab, Library. IDS 100 ∗ Eupolymnia heterobranchia (Johnson, 1901) reported as Eupolymnia crescentis Chamberlin, 1919 changed per Lights 2007. Alex, Dan. 1972. A settling survey of Mason's Marina. Student Report, Bodega Marine Lab, Library. Zoology 157 Alexander, David. 1976. Effects of temperature and other factors on the distribution of LUMBRINERIS ZONATA in the substratum (Annelida: polychaeta). Student Report, Bodega Marine Lab, Library. IDS 100 Amrein, Yost. 1949. The holdfast fauna of MACROSYSTIS INTEGRIFOLIA. Student Report, Bodega Marine Lab, Library. Zoology 112 ∗ Platynereis bicanaliculata (Baird, 1863) reported as Platynereis agassizi Okuda & Yamada, 1954. Changed per Lights 1954 (2nd edition). ∗ Naineris dendritica (Kinberg, 1867) reported as Nanereis laevigata (Grube, 1855) (should be: Naineris laevigata). N. laevigata not in Hartman 1969 or Lights 2007. N. dendritica taken as synonymous with N. laevigata. ∗ Hydroides uncinatus Fauvel, 1927 correct per I.T.I.S. although Hartman 1969 reports Hydroides changing to Eupomatus. Lights 2007 has changed Eupomatus to Hydroides. ∗ Dorvillea moniloceras (Moore, 1909) reported as Stauronereis moniloceras (Moore, 1909). (Stauronereis to Dorvillea per Hartman 1968). ∗ Amrein reported Stylarioides flabellata, which was not recognized by Hartman 1969, Lights 2007 or the Integrated Taxonomic Information System (I.T.I.S.). -

County of Sonoma Local Coastal Program

VI. HARBOR Introduction Harbor and marina facilities, commercial and sport fishing, recreational boating, and harbor construction and maintenance are topics addressed in the Harbor chapter. The Spud Point Master Plan prepared for the Sonoma County Regional Parks Department, the Harbor Discussion Paper prepared by the Harbor Technical Advisory Committee and the Environmental Assessment-Maintenance Dredging Bodega Bay Federal Channel prepared for the United States Army Corps of Engineers provide the basis for the analysis and recommendations. California Coastal Act Policies The coastal act policies are supportive of coastal-dependent development stressing protection of fishing, boating, and necessary support facilities. 30001.5 (d). Assure priority for coastal-dependent development over other development on the coast. 30220. Coastal areas suited for water-oriented recreational activities that cannot readily be provided at inland water areas shall be protected for such uses. 30221. Ocean front land suitable for recreational use shall be protected for recreational use and development unless present and foreseeable future demand for public or commercial recreation activities that could be accommodated on the property is already adequately provided for in the area. 30224. Increased recreational boating use of coastal waters shall be encouraged, in accordance with this division, by developing dry storage areas, increasing public launching facilities, providing additional berthing space in existing harbors, limiting non-water dependent land uses -

Transplanted to a Northern Clime Californian Wives and Children In

TRANSPLANTED TO A NORTHERN CLIME: CALIFORNIAN WIVES AND CHILDREN IN RUSSIAN ALASKA Katherine L. Arndt Elmer E. Rasmuson Library, University of Alaska Fairbanks, P.O. Box 756808, Fairbanks, AK 99775-6808; [email protected] ABSTRACT For nearly thirty years (1812–1841) the Russian-American Company maintained an outpost, Ross, in northern California. During that time, a number of the company’s Alaska Native, Creole, and Rus- sian personnel formed unions with California Native women and fathered children by them. With no priest in residence and priestly visits rare, most of the unions were sanctified by marriage only retro- actively, if at all. This paper traces the evolution of Russian-American Company policy toward such unions and the children born of them, as well as the fate of some of the families who braved the trip north and made Russian Alaska their home. Ross1 (Fig. 1), the Russian colonial outpost in north- Company, subject to recall at any time, many were retained ern California (Fig. 2), has long interested archaeolo- (and some detained) for years on end. Far from friends gists, historians, and ethnographers alike (Hussey 1979). and family in Alaska, they formed ties of friendship and Multidisciplinary research, particularly the Fort Ross kinship among themselves and with the local California Archaeological Project (Lightfoot et al. 1991; Lightfoot Natives. When they did eventually return to Alaska, some et al. 1997) and recently published compendia of archi- of those ties persisted, coloring individuals’ and families’ val documents (Gibson et al. 2014a, 2014b; Istomin et al. social relations long after California was left behind. -

Bodega Bay Area Grounwater Basin

North Coast Hydrologic Region California’s Groundwater Bodega Bay Area Groundwater Basin Bulletin 118 Bodega Bay Area Groundwater Basin • Groundwater Basin Number: 1-57 • County: Sonoma • Surface Area: 2,680 acres Basin Boundaries and Hydrology Bodega Bay lies along the Sonoma County coastline about 55 miles north of San Francisco. The Bodega Bay Area extends approximately 4 miles along the mainland from the area of Salmon Creek to the north to below Cheney Gulch on the south. This area extends inland up to about 1 mile from Bodega Harbor. The area is comprised of the mainland on the east side, Bodega Harbor and Doran Beach, Bodega Head, and the Bodega Tombolo (a sand bar/dune area which connects Bodega Head with the mainland). The Bodega Bay Area Groundwater Basin is defined by the areal extent of Quaternary alluvium, sand dunes, and terrace deposits, but also contains some Cretaceous granitic rocks exposed on Bodega Head. On the mainland side, the groundwater basin is bounded by bedrock of the Franciscan Complex. This basin is bounded on the north by the Fort Ross Terrace Area Groundwater Basin near Salmon Creek. The San Andreas Fault Rift Zone trends northwest through the area of Bodega Bay and Bodega Harbor (Wagner 1982). No major rivers transect the basin; however, Salmon Creek bounds the basin on the north and Cheney Gulch discharges into Bodega Harbor on the south. Annual precipitation in the Bodega Bay Area ranges from approximately 28 inches at Bodega Head to 36 inches on the eastern (inland) side of the basin. Hydrogeologic Information Water Bearing Formations The water-bearing units of primary significance in the Bodega Bay Area include Recent Alluvium in Salmon Creek, Sand Dune Deposits of the Bodega tombolo, and marine terrace deposits. -

36 NEWT HOUGHTS on the K OSTROMITINOV R ANCH, SONOMAC OUNTY, CALIFORNIA Colony Ross, Or Fort Ross As It Is Known Today, Was a Me

36 PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY FOR CALIFORNIA ARCHAEOLOGY, VOL. 19, 2006 NNNEWEWEW THOUGHTSHOUGHTSHOUGHTS ONONON THETHETHE KOSTROMITINOV RANCHANCHANCH, SS, ONOMAONOMAONOMA COUNTYOUNTYOUNTY, CC, ALIFORNIAALIFORNIAALIFORNIA TSIM D. SCHNEIDER Established in 1833, Kostromitinov Ranch was an outlying farming operation intended to supply Colony Ross and to support Russian- American Company (RAC) outposts along the Pacific Rim. Although its precise location is unknown and few ethnohistoric documents mention the operation, Kostromitinov Ranch continues to hold serious potential for culture -contact research. This paper discusses adjunct reconnaissance and survey carried out near Willow Creek during the 2004 summer field school at Fort Ross, archival and map research pertaining to Kostromitinov Ranch, and the possibilities for investigating colonial interactions on a multi-sided and fluid frontier. olony Ross, or Fort Ross as it is known today, was a mercantilist natives living around the Ross settlement it would have been impossible operation and outpost for the Russian-American Company (RAC) to harvest the crops because of a shortage of labor.” A deliberate Cfrom 1812 until 1841. The Ross Colony included the commercial strategy of the RAC thus involved recruitment of local administrative center of Ross, Port Rumianstev at Bodega Harbor, a natives. They could be paid less, required less upkeep, they were familiar hunting artel located on the Farralon Islands, and, later, at least three with extracting local resources such as sea otters, and they had farming or ranching operations located south of Ross (Lightfoot knowledge of local plants and animals that could supplement strained 2005:121). As the distant cornerstone of a once-extensive commercial colonial food resources. -

Northern California Coast Southern Focus Area

15.1 Description of Area 15.1.1 The Land The Northern California Coast-Southern Fours Area is composed of Mendocino, Sonoma, and Marin counties, excluding watersheds that drain into San Francisco Bay (Figure 14). This region of the northern California coast contains three areas with substantial wetland habitats: the coastal wetlands, the interior valleys of the Eel River system, and the interior valleys of the Russian River system. Securement and enhancement of these wetlands will provide nesting, staging, and winter habitat for a variety of waterfowl and many wetland-dependent species. Threatened and endangered species are also present in each of the 15.0 three areas. Limited state and federal protection exists in the form of managed wildlife areas, pants, national seashores or refuges. Wetland enhancement and, in some cases, restoration activities implemented after acquisition will improve NORTHERN and. expand existing wetland habitats. The northern part of the focus area is bounded on the CALIFORNIA east approximately by the dividing ridge between the Eel River and the Sacramento River watersheds. Further south it follows the divide between the water COAST─ sheds of the Russian and Sacramento rivers. Two almost parallel ranges of the Coast Mountain Ranges extend through most of this focus area. The range on SOUTHERN the east is a continuation of the Mayacamas Mountains. In this range, near Potter Valley, rise the two largest rivers of this area: the Eel and Russian rivers. The Eel River flows northward and enters the Pacific Ocean FOCUS AREA just south of Humboldt Bay. The Russian River flows south and then west to empty into the ocean north of Bodega Head. -

Public Access

Sonoma County Mendocino County Local Coastal Plan SubAreas Local Coastal Plan A-4 1 SubArea 1 The Sea Ranch North ! SubArea 2 The Sea Ranch South Public Access 2 SubArea 3 Stewart's Point/Horseshoe Cove 3 SubArea 4 Salt Point Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary SubArea 5 Timber Cove/Fort Ross State Marine Protected Area 4 SubArea 6 High Cliffs/Muniz-Jenner A-7 5 SubArea 7 Duncans Mills California Coastal Trail (CCT) ! SubArea 8 Pacific View/Willow Creek Existing 6 SubArea 9 State Beach/Bodega Bay Gualala Point 7 A-5 SubArea 10 Valley Ford Future !! Regional Park ! 8 A-3 Other Trails ! 9 10 Access Point/Trailhead ! !A-1 !A-2 Base Map Layers Coastal SubArea Park/Public Land Deer Trl ?Ô Parcel Coastal Zone Boundary A-9 Gualala R ! o A-10 Highway Point ck L d ! Cod eew ard R !A-8 Road Perennial Stream Salal Trl lcyon Ha Intermittent Stream ID # NAME A-1 Gualala River North Shore Access Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary A-6 ! Deer Trl A-2 CCT: The Sea Ranch North SubArea A-3 Gualala Point Regional Park A-4 Gualala Point Regional Park Expansion g Helm in The Sea Ranch A-5 Gualala River Water Trail d n u A-11 o A-6 Sea Ranch Bikeway ! S A-7 Coastal Ridge Trail Del Mar Point n A-8 Blufftop Sea Ranch Access Trail Del Mar a A-12 c ! Del Mar Ecological li Reserve e L A-9 The Sea Ranch Recreation Facilities Landing State P e ew Marine Reserve ar A-10 Salal Sea Ranch Access Trail d R Walk-On Beach d Access Trl A-11 Del Mar Landing Ecological Reserve A-12 Walk-On Beach Sea Ranch Access Trail ?Ô Walk-on Beach FIGURE C-PA-1a Public Access L SubArea 1 eew Note: ard R In som e areas th e County’s parcel base isnotbase sominthaligCounty’s parcel In e nmareas e entwithth coastline. -

Sonoma Coast State Park Brochure

Our Mission The mission of California State Parks is to provide for the health, inspiration and Sonoma Coast education of the people of California by helping Sixteen miles of to preserve the state’s extraordinary biological diversity, protecting its most valued natural and awe-inspiring shoreline State Park cultural resources, and creating opportunities for high-quality outdoor recreation. offer myriad opportunities to create unforgettable memories — stroll the beach, fish, sunbathe, or unpack a family picnic. California State Parks supports equal access. Prior to arrival, visitors with disabilities who need assistance should contact the park at (707) 875-3483. If you need this publication in an alternate format, contact [email protected]. CALIFORNIA STATE PARKS P.O. Box 942896 Sacramento, CA 94296-0001 For information call: (800) 777-0369 (916) 653-6995, outside the U.S. 711, TTY relay service www.parks.ca.gov Sonoma Coast State Park 3095 Highway 1 Bodega Bay, CA 94923 (707) 875-3483 or (707) 865-2391 © 2004 California State Parks (Rev. 2017) I magine broad, sandy beaches, secluded is now Marin County. These groups built western wallflower, verbena, and dozens of coves, rugged headlands, natural arches, seasonal villages of redwood bark houses other species of native wildflowers. a craggy coastline with fertile tide pools, along rivers and streams and near today’s In 1951 a program was begun to stabilize and offshore reefs — this is Sonoma Coast Bodega Bay. Both groups were accomplished the drifting sand and keep it from filling State Park, one of California’s most scenic basket makers. The Russian and Aleutian fur Bodega Bay. -

JETTIES at BODEGA HARBOR Orville T. Magoon1, Donald D. Treadwell2, and Paul S. Atwood3 Bodega Harbor, a Lagoon Connected to Bode

JETTIES AT BODEGA HARBOR Orville T. Magoon1, Donald D. Treadwell2, and Paul S. Atwood3 To create and maintain a navigable entrance for small craft between the Pacific Ocean and the natural lagoon now referred to as Bodega Harbor, the construction of two rubble-mound jetties and the associated dredging of interior channels were authorized by the United States Congress in the late 1930s. The jetties were built by the United States Army Corps of Engineers in the early 1940s. Elements of the planning, design, construction, monitoring, and maintenance of the jetties are discussed herein. Keywords: rubble-mound jetties; long-term performance; monitoring; maintenance; Bodega Bay; Bodega Harbor INTRODUCTION Bodega Harbor, a lagoon connected to Bodega Bay and the Pacific Ocean, is located on the California coast of the United States about 50 miles north of San Francisco. The Pacific Ocean areas offshore of Bodega Bay are excellent for both commercial and recreational fishing. However, the natural unimproved entrance to Bodega Harbor, both shallow and unstable, was very difficult to navigate safely. The project undertaken in the early 1940s by the United States government to improve the situation included two entrance channel jetties, a bulkhead to help retain the natural sandspit, and dredging of interior channels and turning basins. Figure 1 is an aerial view of the jetties, the sandspit, a portion of the dredged channels, and the seaward (western) end of the peninsula known as Bodega Head. Figure 1. Aerial View of Jetties and Dredged Entrance Channel at Bodega Harbor PHYSICAL AND GEOLOGIC SETTING The climate at Bodega Harbor in western Sonoma County is temperate and there is little variation between summer and winter temperatures with few days falling below freezing. -

Spud Point Marina History

Spud Point Marina History by Sue Tichava - 2017 The building of Spud Point Marina in Bodega Bay harbor meanders through a maze of 52 years of bureaucracy on the county, state and federal levels. It began in 1933 and ended with the opening of the Marina in 1985. The opening was followed immediately by the collapse of the local fishing industry. In an attempt to keep it brief, a lot of material has not been included, but hopefully a picture will emerge of the tremendous effort it took to get Spud Point Marina built, and then the despair at watching the bottom fall out of the commercial fishing industry and it’s impact on the Marina and the Bodega Bay Community. Commercial fishing has been the primary industry in Bodega Bay for at least 99 years, since the Smith Brothers started selling fish to Paladini, a fish marketing company in San Francisco in 1919. Sport fishing has always been popular as well and has been bringing visitors to the Sonoma coast since the 1920s. It was the dream of the earliest local fishermen to develop the inner bay to create a safe harbor in order for the fishing industry to thrive. Over the next 25 years, the inner bay was developed with wharves, small private marinas, fish processing plants, restaurants and cafes, motels, gas stations and markets to provide the necessary services to Bodega Bay residents, fishermen and visitors. These included the Smith Brothers, the Tides, Shaw’s Marina (Porto Bodega), Mason’s Marina, Meredith Fisheries (defunct) and Lazio Fish Company (defunct) to name just a few.