Bodega Bay Field Trip Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Pacific Coast Breeding Window Survey

2020 Breeding Window Survey for Snowy Plovers on U.S. Pacific Coast Note: March 17, 2020 we entered into coronavirus pandemic and as a result some segments were not monitored during the window period 2020 Adult Breakdown County (listed North to South) Site (location) OWNER 2020 male fem. sex unknown? Date of Survey (window) Primary Observer(s) & Additional Notes Grays Harbor Copalis Spit WA State Parks 4 2 1 1 20-May-20 C. Sundstrom, W. Michaelis Conner Creek WA State Parks 4 2 2 0 20-May-20 C. Sundstrom, W. Michaelis Damon Point/Oyhut WA State Parks, WDFW 2 1 1 0 20-May-20 C. Sundstrom, W. Michaelis Ocean Shores to Ocean City WA State Parks, Private 0 0 0 0 22-May-20 C. Sundstrom, W. Michaelis Oyhut Spit County Total 10 5 4 1 Pacific Midway Beach Private, WA State Parks 37 23 13 1 19-May-20 C. Sundstrom, W. Michaelis Graveyard Shoalwater Indian Tribe no survey due to coronavirus restrictions and staffing limitations North Willapa Bay Islands USFWS, DNR no survey due to coronavirus restrictions and staffing limitations Leadbetter Point NWR USFWS, WA State Parks no survey due to coronavirus restrictions and staffing limitations South Long Beach Private no survey due to coronavirus restrictions and staffing limitations Benson Beach Private no survey due to coronavirus restrictions and staffing limitations County Total 37 23 13 1 Washington Total 47 28 17 2 Clatsop Fort Stevens State Park (ClatsopACOE, OPRD 8 2 6 0 15-May-20 P. Schmidt, V. Loverti Sunset Beach no survey due to coronavirus restrictions and staffing limitations Del Rey Beach no survey due to coronavirus restrictions and staffing limitations Gearhart Beach no survey due to coronavirus restrictions and staffing limitations Camp Rilea DOD 0 0 0 0 27-May-20 S. -

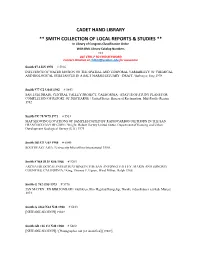

Smith Collection of Local Reports & Studies (PDF)

CADET HAND LIBRARY ** SMITH COLLECTION OF LOCAL REPORTS & STUDIES ** In Library of Congress Classification Order With BML Library Catalog Numbers *** USE CTRL-F TO FIND KEYWORD Contact librarian at [email protected] for assistance Smith 87.3 I65 1978 # 5916 INFLUENCE OF WATER MOTION ON THE SPATIAL AND TEMPORAL VARIABILITY OF CHEMICAL AND BIOLOGICAL SUBSTANCES IN A SALT MARSH ESTUARY : DRAFT / Imberger, Jorg 1978. Smith 977 C2 U645 1982 # 5843 SAN LUIS DRAIN, CENTRAL VALLEY PROJECT, CALIFORNIA : STATUS OF STUDY PLANS FOR COMPLETION OF REPORT OF DISCHARGE / United States. Bureau of Reclamation. Mid-Pacific Region 1982. Smith CC 78 W75 1971 # 5513 MAP SHOWING LOCATIONS OF SAMPLES DATED BY RADIOCARBON METHODS IN THE SAN FRANCISCO BAY REGION / Wright, Robert Harvey United States. Department of Housing and Urban Development Geological Survey (U.S.) 1971. Smith DS 521 U65 1980 # 6040 SOUTHEAST ASIA / University Microfilms International 1980. Smith F 868 S135 K56 1966 # 5265 ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS IN THE SAN ANTONIO VALLEY, MARIN AND SONOMA COUNTIES, CALIFORNIA / King, Thomas F. Upson, Ward Milner, Ralph 1966. Smith G 782 G85 1973 # 5776 JAN MAYEN : EN BIBLIOGRAFI / Gulliksen, Elin Hegstad Kongelige Norske videnskabers selskab. Museet 1973. Smith G 4362 N42 N48 1980 # 6233 [NEWARK SLOUGH] 1980?. Smith GB 126 C2 N48 1980 # 5482 [NEWARK SLOUGH] / [Photographer not yet identified] [1980?]. Smith GB 126 C2 S65 1998 # 6267 TOMALES ENVIRONMENT / Smith, Stephen V. Hollibaugh, James T. University of Hawaii. Schooll of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology Tiburon Center for Environmental Studies [1998?]. Smith GB 428 G46 1974 # 6154 GEOLOGY / Environmental Research Consultants (Firm) 1974. Smith GB 451 M35 1960 # 5777 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF COASTAL GEOMORPHOLOGY OF THE WORLD / McGill, John T. -

Dane Kristopher Behrens Dissertation Doctor Of

The Russian River Estuary: Inlet Morphology, Management, and Estuarine Scalar Field Response By DANE KRISTOPHER BEHRENS B.S. (University of California, Davis) 2006 M.S. (University of California, Davis) 2008 DISSERTATION Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Civil and Environmental Engineering in the OFFICE OF GRADUATE STUDIES of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA DAVIS Approved: ______________________ Fabián Bombardelli, Co-Chair ______________________ John Largier, Co-Chair ______________________ David Schoellhamer ______________________ Gregory Pasternack Committee in Charge 2012 i © 2012 by Dane Kristopher Behrens. All Rights Reserved. ii Dane Kristopher Behrens December 2012 Civil and Environmental Engineering The Russian River Estuary: Inlet morphology, Management, and Estuarine Scalar Field Response Abstract Bar-built estuaries with unstable tidal inlets are widespread in Mediterranean climates and along wave-exposed coasts. While similarly important to coastal sediment balances and estuarine ecosystems, and more numerous than larger inlet systems, they suffer from a relative lack of understanding. This is a result of the setting: bar-built estuaries lie at a nexus of coastal and fluvial environments, often behaving like lakes with extreme variability in boundary conditions. At the ocean-side boundary, inlet channel blockage from wave-driven sedimentation is common, leading to water levels in the lagoon that are consistently higher than ocean levels (perched conditions) or to complete disconnection between the lagoon and the ocean (inlet closure). During times when the inlet channel allows tidal conveyance, flood tides provide saline, nutrient-rich water and vigorous turbulent mixing. Inlet closure traps seawater in the estuary and transforms these systems into salt-stratified coastal lakes. -

Sonoma Coast

Our Mission The mission of California State Parks is his awe-inspiring to provide for the health, inspiration and T Sonoma Coast education of the people of California by helping shoreline offers a wealth to preserve the state’s extraordinary biological diversity, protecting its most valued natural and of opportunities for State Park cultural resources, and creating opportunities for high-quality outdoor recreation. wholesome fun. Whether you like to stroll along the beach, fish, sunbathe, or settle down for a California State Parks supports equal access. Prior to arrival, visitors with disabilities who family picnic, you will need assistance should contact the park at (707) 875-3483. This publication can be be able to create many made available in alternate formats. Contact [email protected] or call (916) 654-2249. unforgettable moments. CALIFORNIA STATE PARKS P.O. Box 942896 Sacramento, CA 94296-0001 For information call: (800) 777-0369 (916) 653-6995, outside the U.S. 711, TTY relay service www.parks.ca.gov Discover the many states of California.™ Sonoma Coast State Park 3095 Highway 1 Bodega Bay, CA 94923 (707) 875-3483 or (707) 865-2391 © 2004 California State Parks (Rev. 2012) I magine broad, sandy beaches, secluded The Pomo and the Miwok were among several used to protect dikes in the Netherlands. coves, rugged headlands, natural arches, a Native Californian groups who actively resisted This species is now considered invasive, so craggy coastline with fertile tide pools and the drastic changes brought by the fur trappers, California State Parks staff and volunteers offshore reefs—this is Sonoma Coast State Spanish missionaries are removing the beach Park, one of California’s most scenic attractions. -

Jenner Visitor Center Sonoma Coast State Beach Docent Manual

CALIFORNIA STATE PARKS Jenner Visitor Center Sonoma Coast State Beach Docent Manual Developed by Stewards of the Coast & Redwoods Russian River District State Park Interpretive Association Jenner Visitor Center Docent Program California State Parks/Russian River District 25381 Steelhead Blvd, PO Box 123, Duncans Mills, CA 95430 (707) 865-2391, (707) 865-2046 (FAX) Stewards of the Coast and Redwoods (Stewards) PO Box 2, Duncans Mills, CA 95430 (707) 869-9177, (707) 869-8252 (FAX) [email protected], www.stewardsofthecoastandredwoods.org Stewards Executive Director Michele Luna Programs Manager Sukey Robb-Wilder State Park VIP Coordinator Mike Wisehart State Park Cooperating Association Liaison Greg Probst Sonoma Coast State Park Staff: Supervising Rangers Damien Jones Jeremy Stinson Supervising Lifeguard Tim Murphy Rangers Ben Vanden Heuvel Lexi Jones Trish Nealy Cover & Design Elements: Chris Lods Funding for this program is provided by the Fisherman’s Festival Allocation Committee, Copyright © 2004 Stewards of the Coast and Redwoods Acknowledgement page updated February 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents 1 Part I The California State Park System and Volunteers The California State Park System 4 State Park Rules and Regulations 5 Role and Function of Volunteers in the State Park System 8 Volunteerism Defined 8 Volunteer Standards 9 Interpretive Principles 11 Part II Russian River District State Park Information Quick Reference to Neighboring Parks 13 Sonoma Coast State Beach Information 14 Sonoma Coast Beach Safety 17 Tide Pooling -

Appendix 1. Bodega Marine Lab Student Reports on Polychaete Biology

Appendix 1. Bodega Marine Lab student reports on polychaete biology. Species names in reports were assigned to currently accepted names. Thus, Ackerman (1976) reported Eupolymnia crescentis, which was recorded as Eupolymnia heterobranchia in spreadsheets of current species (spreadsheets 2-5). Ackerman, Peter. 1976. The influence of substrate upon the importance of tentacular regeneration in the terebellid polychaete EUPOLYMNIA CRESCENTIS with reference to another terebellid polychaete NEOAMPHITRITE ROBUSTA in regard to its respiratory response. Student Report, Bodega Marine Lab, Library. IDS 100 ∗ Eupolymnia heterobranchia (Johnson, 1901) reported as Eupolymnia crescentis Chamberlin, 1919 changed per Lights 2007. Alex, Dan. 1972. A settling survey of Mason's Marina. Student Report, Bodega Marine Lab, Library. Zoology 157 Alexander, David. 1976. Effects of temperature and other factors on the distribution of LUMBRINERIS ZONATA in the substratum (Annelida: polychaeta). Student Report, Bodega Marine Lab, Library. IDS 100 Amrein, Yost. 1949. The holdfast fauna of MACROSYSTIS INTEGRIFOLIA. Student Report, Bodega Marine Lab, Library. Zoology 112 ∗ Platynereis bicanaliculata (Baird, 1863) reported as Platynereis agassizi Okuda & Yamada, 1954. Changed per Lights 1954 (2nd edition). ∗ Naineris dendritica (Kinberg, 1867) reported as Nanereis laevigata (Grube, 1855) (should be: Naineris laevigata). N. laevigata not in Hartman 1969 or Lights 2007. N. dendritica taken as synonymous with N. laevigata. ∗ Hydroides uncinatus Fauvel, 1927 correct per I.T.I.S. although Hartman 1969 reports Hydroides changing to Eupomatus. Lights 2007 has changed Eupomatus to Hydroides. ∗ Dorvillea moniloceras (Moore, 1909) reported as Stauronereis moniloceras (Moore, 1909). (Stauronereis to Dorvillea per Hartman 1968). ∗ Amrein reported Stylarioides flabellata, which was not recognized by Hartman 1969, Lights 2007 or the Integrated Taxonomic Information System (I.T.I.S.). -

David E. Pesonen: the Battle for Bodega Head Stacey Olson

David E. Pesonen: The Battle for Bodega Head Stacey Olson Individual Exhibit Senior Division (Exhibit: 477 student composed words) (Process Paper: 496 words) I decided to research David E. Pesonen and the battle for Bodega Head when I learned that PG&E had intended to build a nuclear power plant on Bodega Head in the 1960s. Initially, I was uncertain about choosing a local history topic, but after some research I decided that Pesonen’s leadership had a significant legacy far beyond Sonoma County. Pesonen’s leadership style enabled a grassroots protest to defeat the largest power company in the country. Through my research I’ve discovered that the legacy of this victory extended beyond the issue of nuclear power, influenced the modern environmental movement, and became a model for participatory democracy. I started my research by visiting the Sonoma State University Regional History Collection and looking at documents and photographs. I accessed special reports and oral histories at the Bancroft Library and the National Archives and Records Administration. My best secondary source was Critical Masses by Thomas Wellock. I also found useful documents at the Eisenhower Presidential Library and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Interviews were an integral source of information. I interviewed David Pesonen, Doris Sloan, and journalists who covered the battle. My interview with David Pesonen was key to understanding his leadership style and why he was significant. Beyond my interviews, my best primary source was A Visit to Atomic Park by David Pesonen. I balanced my research in several ways. For PG&E’s perspective, I researched the demands for energy, the Atoms for Peace initiative, and interviewed a local citizen who wanted the power plant. -

Goat Rock Beach Jetty Feasibility Study

Goat Rock Beach Jetty Feasibility Study Matt Brennan, PhD, PE Dane Behrens, PhD, PE June 11, 2015 Monte Rio Community Center National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) 2008 Biological Opinion (BO) Estuary Management Objectives During the dry season (May 15 – October 15) Less of this… More of this… Tidal Outflow Perched Inflow & only Outflow & & salty fresh Why Study the Jetty? Freshwater lagoon habitat May 15 – Oct 15 Inlet morphology Evolution of the Jetty Jetty Components Seismic Beach Berm Profile Beach sand Beach Jetty parking lot Artificial rock fill groin Beach sand Bedrock Bedrock Rockfill Beach Morphology: Influence of Construction Adjacent to Goat Rock Prior to jetty construction, Goat Rock was only connected to the shore by a tombolo (low-lying sand spit). 1875 Beach Morphology: Influence of Construction Adjacent to Goat Rock Shoreline accretion of 1.5 ft/yr Shoreline erosion of 0.8 ft/yr Beach Morphology: Influence of Jetty Access Elements Beach widening of 2 ft/yr Beach Morphology: Influence of Jetty Access Elements Extensive migration • Sites with extensive inlet migration have lower, nearly uniform beach spits Limited migration • Sites with less frequent inlet migration or movement have higher, less uniform beach crests • Jetty access elements likely widened and maintained high beach south of the groin Inlet Morphology Jetty’s influence on self-breaching 1. Open 2. Closed 10/7/12 10/8/12 3. Rising water levels 4. Self-breach at jetty 10/15/12 10/16/12 Groundwater Seepage BEACH LAGOON groundwater seepage cfs) Seepage ( Water -

Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary Advisory Council

Sonoma-Marin Coastal Regional Sediment Management Report Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary Advisory Council February 2018 Report Citation GFNMS Advisory Council, 2018. Sonoma-Marin Coastal Regional Sediment Management Report. Report of the Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary Advisory Council for the Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary. San Francisco, CA. 197 pp. Cover photos (top left) Bodega Harbor Dredging, Cea Higgins (top right) Gleason Beach area, Doug George (bottom left) Aerial view of Stinson Beach and Seadrift, Bob Wilson (bottom right) Bolinas Highway revetment, Kate Bimrose This work was made possible with support from: i Sonoma-Marin Coastal Regional Sediment Management Working Group Members Chair: Cea Higgins, Sonoma Coast Surfrider; Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary (GFNMS) Advisory Council Hattie Brown, Sonoma County Regional Parks Jon Campo, Marin County Parks Clif Davenport, Coastal Sediment Management Workgroup Ashley Eagle-Gibbs, Environmental Action Committee of West Marin Brook Edwards, Wildlands Conservancy Leslie Ewing, California Coastal Commission Luke Farmer, Wildlands Conservancy Shannon Fiala, California Coastal Commission Stefan Galvez, Caltrans Brannon Ketcham, National Park Service, Point Reyes National Seashore John Largier, UC Davis Bodega Marine Lab, Sanctuary Advisory Council chair Neil Lassettre, Sonoma County Water Agency Bob Legge, Russian Riverkeeper Jack Liebster, County of Marin Planning Department Jeannine Manna, California Coastal Commission Abby Mohan, -

California's Best Beaches North of San Francisco

California’s Best Beaches North of San Francisco Author’s Note: This article “California’s Best Beaches North of San Francisco” is also a chapter in my travel guidebook/ebook Northern California Travel: The Best Options. That book is available in English as a book/ebook and also as an ebookin Chinese. Parallel coverage on Northern California occurs in my latest travel guidebook/ebook Northern California History Travel Adventures: 35 Suggested Trips. All my travel guidebooks/ebooks on California can be seen on myAmazon Author Page. By Lee Foster Summer entices the connoisseur of California’s best beaches to the coast north and south of San Francisco. Whether you want to bronze your skin, marvel at tide pools, escape from urban life, or simply restore your lungs in the bracing salt air, the nearby beaches offer something for everyone. If you think you already know the roughly 250 miles of coast between Point Arena and Carmel, peruse the following selections. You may have overlooked these well-known and lesser-known beaches, all true delights. Moreover, some beaches also boast features that may be new to you, such as an improved hiking trail between Bodega Head and Bodega Dunes. If you haven’t recently explored the beauty of the coast, many aspects beckon throughout the year. For example, marvel at the salubrious spring and fall sunlight with its visual clarity. Or imbibe the pensive fogs of summer. On the other hand, savor the invigorating storms of winter as the pageant of the seasons unfolds. This article covers beaches north of San Francisco. -

Socogazette 9-18.Indd

What if I told you last year there were 2,412,151 cigarette butts or 1,739743 food wrappers all collected from beach cleanups. Shocking, right? Well here’s one more: enough balloons were collected to lift a great white shark according to Ocean Conservancy in 2017. All that trash would still be on the beaches if people like you didn’t help. This year International Coastal Cleanup is Saturday, September 15, 2018. There are cleanups taking place all over the world; many in Sonoma County. So, choose your beach or river and come out and make a difference. Let’s try and get all the trash out before the rains come. If you cannot make the September 15th cleanup there are other ongoing/monthly events throughout the county. City of Santa Rosa- 34th Roseland Action Adopt-A-Beach Coastwalk- California Riverkeeper Laguna de Annual Sonoma County Creek Oct 27 at 10am The Coastal Commission® runs a year- Coastal Clean-up Day 31st Annual Russian River Santa Rosa to Coast Clean Up Santa Rosa, Meet at: 1683 Burbank Ave round cleanup program called Adopt- Sept 15th 9am-12pm Watershed Cleanup Foundation Sept 15th 9:30-12 (Roseland Creek Elementary School) A-Beach®. Help us keep the California coast debris-free all year long. Register at: www.coastwalk.org Sept 15th 8am-1pm The Great Santa Rosa Roseland Creek Clean up and also a Cleanup 9-12 and Volunteer Roseland Neighbor Wood cleanup. Info: www.coastal.ca.gov Register at: russianrivercleanup.org Laguna Cleanup 1698 Hazel Street (Olive Park Footbridge) Appreciation Picnic on the coast from We will be working along the creek Russian Riverkeeper will be organizing (Part of Coastal Keep the beaches clean! Join the 34rd 1-3 (details and tickets for the picnic between 1370 Burbank Ave. -

County of Sonoma Local Coastal Program

VI. HARBOR Introduction Harbor and marina facilities, commercial and sport fishing, recreational boating, and harbor construction and maintenance are topics addressed in the Harbor chapter. The Spud Point Master Plan prepared for the Sonoma County Regional Parks Department, the Harbor Discussion Paper prepared by the Harbor Technical Advisory Committee and the Environmental Assessment-Maintenance Dredging Bodega Bay Federal Channel prepared for the United States Army Corps of Engineers provide the basis for the analysis and recommendations. California Coastal Act Policies The coastal act policies are supportive of coastal-dependent development stressing protection of fishing, boating, and necessary support facilities. 30001.5 (d). Assure priority for coastal-dependent development over other development on the coast. 30220. Coastal areas suited for water-oriented recreational activities that cannot readily be provided at inland water areas shall be protected for such uses. 30221. Ocean front land suitable for recreational use shall be protected for recreational use and development unless present and foreseeable future demand for public or commercial recreation activities that could be accommodated on the property is already adequately provided for in the area. 30224. Increased recreational boating use of coastal waters shall be encouraged, in accordance with this division, by developing dry storage areas, increasing public launching facilities, providing additional berthing space in existing harbors, limiting non-water dependent land uses