What Hobby Lobby and Abortion Conscience Clauses Teach About Specific Exemptions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

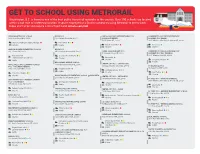

GET to SCHOOL USING METRORAIL Washington, D.C

GET TO SCHOOL USING METRORAIL Washington, D.C. is home to one of the best public transit rail networks in the country. Over 100 schools are located within a half mile of a Metrorail station. If you’re employed at a District school, try using Metrorail to get to work. Rides start at $2 and require a SmarTrip® card. wmata.com/rail AIDAN MONTESSORI SCHOOL BRIYA PCS CARLOS ROSARIO INTERNATIONAL PCS COMMUNITY COLLEGE PREPARATORY 2700 27th Street NW, 20008 100 Gallatin Street NE, 20011 (SONIA GUTIERREZ) ACADEMY PCS (MAIN) 514 V Street NE, 20002 2405 Martin Luther King Jr Avenue SE, 20020 Woodley Park-Zoo Adams Morgan Fort Totten Private Charter Rhode Island Ave Anacostia Charter Charter AMIDON-BOWEN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL BRIYA PCS 401 I Street SW, 20024 3912 Georgia Avenue NW, 20011 CEDAR TREE ACADEMY PCS COMMUNITY COLLEGE PREPARATORY 701 Howard Road SE, 20020 ACADEMY PCS (MC TERRELL) Waterfront Georgia Ave Petworth 3301 Wheeler Road SE, 20032 Federal Center SW Charter Anacostia Public Charter Congress Heights BROOKLAND MIDDLE SCHOOL Charter APPLETREE EARLY LEARNING CENTER 1150 Michigan Avenue NE, 20017 CENTER CITY PCS - CAPITOL HILL PCS - COLUMBIA HEIGHTS 1503 East Capitol Street SE, 20003 DC BILINGUAL PCS 2750 14th Street NW, 20009 Brookland-CUA 33 Riggs Road NE, 20011 Stadium Armory Public Columbia Heights Charter Fort Totten Charter Charter BRUCE-MONROE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL @ PARK VIEW CENTER CITY PCS - PETWORTH 3560 Warder Street NW, 20010 510 Webster Street NW, 20011 DC PREP PCS - ANACOSTIA MIDDLE APPLETREE EARLY LEARNING CENTER 2405 Martin Luther -

Food Resource List

General Information Updated April 17, 2020 Visit the Capital Area Food Bank website to find out where they have Pop Up sites -- their website is www.capitalareafoodbank.org and when you get to the site click on the yellow alert banner at the top --- this will give current information on the Pop Ups. District of Columbia Resources Newly Released As Of April 13, 2020 Mayor Muriel Bowser launched 10 weekday grocery distribution sites at District schools to help families access meals and other resources during the coronavirus (COVID-19) public health emergency. The grocery distribution sites are being launched in partnership with Martha’s Table and DC Central Kitchen. The sites are available to all families and are open Monday – Friday, 12:30 p.m. – 2:00 p.m. Residents can pick up pre-packed grocery bags, which include fresh produce and dry goods. Groceries are being distributed on a first come, first served basis. Below is a list of the distribution sites: Mondays Tuesdays Wednesdays Thursdays Fridays Brookland Middle Kelly Miller Coolidge High Anacostia Ballou High School School Middle School School/Ida B. Wells High School (Ward 8) Ward 5) (Ward 7) Middle School (Ward 8) 3401 4th Street, SE 150 Michigan 301 49th Street, NE (Ward 4) 1601 16th Street, SE Avenue, NE 6315 5th Street, NW Eastern Senior Stanton Elementary Woodson Kimball Elementary Columbia Heights High School School High School School Education Campus (Ward 6) (Ward 8) (Ward 7) (Ward 7) (Ward 1) 1700 East Capitol 2701 Naylor Road, SE 540 55th Street, NE 3375 Minnesota 3101 16th Street, NW Street, NE Avenue, SE For Seniors Starting March 23rd, home delivery will be available to vulnerable seniors in need of emergency food. -

2019 LPF-Greater Washington Annual Report

2019 ANNUAL REPORT G r e a t e r W a s h i n g t o n A NOTE FROM THE DIRECTOR Supporters, Even after six years of running Leveling the Playing Field in Washington DC I am still in awe of the support from our local youth sports community. We are so fortunate to be able to engage members of the Greater Washington community on a daily basis who feel passionately about what participation in youth sports can do for young people. It is that continued passion that led to 2019 being yet another year of deep impact for our program. Whether it was a holiday collection at The St James, a fundraiser at District Taco or being chosen as the beneficiary of the annual Morgan Stanley Tee Off for Tots Charity Golf Tournament, the perpetual investment from the community has allowed us to continue providing free sports equipment to schools and youth programs throughout the DC area. Without the support from the Washington Capitals and local youth hockey families we would not have been able to help St Mary’s Ryken HS launch a girls JV hockey program. If the local little leagues were not so willing to invite us to run collection drives at their games we would not be able to ensure that little leagues in SE DC could provide their families with free gear and keep their registration fees affordable. Were it not for local private schools bringing students to our warehouse to volunteer we would not be able to ensure that Title I schools are able to offer enhanced PE programming and after school sports activities. -

2017-2018 LIFT Guidebook (Career Ladder)

2017–2018 Leadership Initiative For Teachers Cover photos by Daisa Gainey, and District of Columbia Public Schools Table of Contents Letter from the Chancellor 3 Introduction to LIFT 4 LIFT Stages: Overview 7 Advancing up the LIFT Ladder 10 Your Starting LIFT Stage 12 More Information about IMPACTplus 14 LIFT Stages: In-Depth View 21 Teacher Stage 21 Established Teacher Stage 23 Advanced Teacher Stage 25 Distinguished Teacher Stage 27 Expert Teacher Stage 29 Leadership Opportunities Catalog 30 Concluding Message 53 DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA PUBLIC SCHOOLS 1 2 Letter from the Chancellor Dear DCPS Teachers, When I became Chancellor of DCPS, I had the pleasure of visiting all 115 schools across the city and witnessing our remarkable teachers in action. I was and continue to be impressed with the passion, skill, and joy our educators bring to the classroom. The progress DCPS made in recent years was only possible because of the extraordinary talent assembled here. Our schools and city are fortunate to have you, and we want you to feel supported and sustained in your careers. Recently, the National Council on Teacher Quality recognized DCPS as a Great District for Great Teachers, with an outstanding designation. We received this distinction for several reasons, one of which is the Leadership Initiative for Teachers career ladder, or LIFT. Through LIFT, exceptional teachers are recognized and rewarded for their continued service to DCPS. Because LIFT provides opportunities for teachers to take on leadership roles without having to leave the classroom, students directly benefit from their teachers’ professional growth. In order to continue that success, we must remain focused on ensuring excellence and equity throughout the district. -

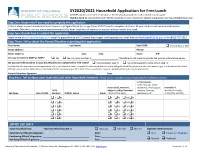

SY2020/2021 Household Application for Free Lunch All DCPS Students Receive Free Breakfast

SY2020/2021 Household Application for Free Lunch All DCPS students receive free breakfast. Select schools provide free afterschool snack/supper. Use this form to request free lunch for the students in your household. Submit 1 application per household/school year. Step One: Determine if you need to complete this application. If ALL students in your household attend a Community Eligible School (list on pg 2) you DO NOT need to complete this form. All your students will automatically receive free lunch. Otherwise, you are encouraged to complete this form, regardless of whether or not you want to receive free lunch. Step Two: Decide how to submit this application. Apply online at dcps.heartlandapps.com, bring this paper form to a DCPS school that accepts lunch applications, email forms to [email protected], or fax @202-727-2512 Step Three: Tell us about the Parent/Guardian submitting this application. First Name: Last Name: Last 4 SSN: ❑ I do not have a SSN Email address: Phone: Home Address: Apt: City: State: ZIP: Are you enrolled in SNAP or TANF? ❑ No ❑ Yes, my case number is: I therefore do not need to provide the income information below. Do you want the students in your household to be considered for free meals? ❑ Yes (complete step 4) ❑ No (write student’s name only in step 4) I certify that all information on this application is true and that all income is reported. I understand that the school will get Federal funds based on the information I give. I understand that school officials may verify the information. -

District of Columbia State Athletic Association Announces Student-Athlete Academic Scholarship Winners

For Immediate Release Contact: May 12, 2016 Jesse Harteis 202-344-9805 [email protected] Josh Barr 202-309-5021 [email protected] District of Columbia State Athletic Association Announces Student-Athlete Academic Scholarship Winners Washington, D.C. -- The District of Columbia State Athletic Association (DCSAA) is proud to announce that 16 high school seniors have been selected to receive $1,000 college scholarships as part of the DCSAA’s partnerships with Modell’s Sporting Goods and Wendy’s restaurants. The Student-Athlete Academic Scholarship Program winners come from 15 different high schools in the District, including public schools, public charter schools and independent/private schools. The scholarship awards will be used to help cover the cost of tuition and fees, room and board and books at an accredited college or university. A reception to honor the scholarship winners will be held on Wednesday, May 18 at the Charles Sumner School Museum and Archives, 1201 17th Street NW. The event is open to media. “Thanks to commitment of partners like Modell’s and Wendy’s, we are able to continue the DCSAA scholarship program and honor these young men and women for all of their contributions in the classroom, in athletics and in the community,” DCSAA Executive Director Clark Ray said. “Our schools are producing many fine young men and women and we are excited to be able to help them as they take the next steps in their education.” The scholarship winners are: Ariel Austin, Maret School, Volleyball and Basketball Jamar Bolden, Coolidge Senior High School, Football and Basketball Tristan Colaizzi, Georgetown Day School, Cross-Country and Track and Field Johanna Flores, E.L. -

School Profiles Directory C. DC Public Charter School Board: Find a Charter School D

10. Placements a. NCLB Teacher Qualifications Request Information b. DCPS: School Profiles Directory c. DC Public Charter School Board: Find a Charter School d. OSSE LEA Status of Charter Schools e. MySchoolsDC Lottery Information f. OSSE Approved Nonpublic Day Schools g. OSSE Approved Nonpublic Residential Programs h. OSSE Approved Nonpublic Psychiatric Residential Treatment Facilities i. Sample Referral Packet to a Non-Public School j. DCPS Special Education Programs link k. School and Program Information (Including Non- Traditional Programs) No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Parent’s Right to Know Request Form Student’s Name: _____________________________________________________ (Child’s) Last Name First Name MI School Name: _______________________________________________________ Parent’s Name: ______________________________________________________ Last Name First Name MI Parent’s Address:_________________________________________________________________________ City : ________________________ State: _______ Zip: ____________Contact #: (______)_____-________ I am requesting information on my child’s teacher(s) and/or paraprofessional(s) named below: (Please indicate the last name, first name of the teacher(s) / paraprofessional(s), if necessary contact the school office for this information) No. Last Name, First Name MI Position (Teacher /Parapro) Subject taught 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Note: This notice is to request information on the teacher(s) and/or paraprofessional(s) qualifications that parents have a right to know under NCLB. Notification of a teacher’s qualifications does not include the right to request that your child be reassigned to another classroom. Fax this form at (202) 535-2483 to the attention of Licensure and Highly Qualified Compliance Unit Parent/ Guardian’s Signature: ______________________________________ Date: ____/______/_________ Verification from School Office I verify that the personnel named above is/was the teacher(s) and/or paraprofessional(s) for the stated student. -

Food System Assessment

FOOD SYSTEM ASSESSMENT The District’s efforts to support a more equitable, healthy, and sustainable food system 2018 Published Spring 2019 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS LETTER FROM THE MAYOR OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA.................................................................. 3 LETTER FROM THE DC FOOD POLICY DIRECTOR .....................................................................................................4 DISTRICT AGENCY ACRONYMS ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 METHODOLOGY AND DATA COLLECTION .......................................................................................................................... 6 OVERVIEW OF THE FOOD ASSESSMENT..................................... ........................................................... 7 OVERVIEW OF THE DISTRICT’S FOOD SYSTEM GOALS AND PRIORITIES..................................... 8 SECTION 1: IMPROVING FOOD SECURITY AND HEALTH IN THE DISTRICT FOOD INSECURITY .......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 10 FOOD INSECURITY AND HEALTH ..............................................................................................................................................................................11 FEDERAL NUTRITION ASSISTANCE PROGRAMS ................................................................................................................................................ -

Letter from Education Leaders in DC

August 22, 2017 To Our DC Community, We are extremely excited about the back to school season! Schools are places where our students grow as individuals – where they learn more about themselves, how to relate to others, and important lessons about our nation. We also recognize that the events in Charlottesville, Virginia have stirred strong emotions in our District and nationwide. It is difficult to watch these horrific events unfold mere hours away from where we live. Over the past week, we’ve heard concerns and fears from residents of all ages, races, and backgrounds, fears that are justified by simply watching local news or listening to your local radio station. We, like many others, are frustrated by the race-based hatred we see in our country. As DC education leaders, we are writing today to affirm that we are unequivocally committed to protecting our schools and our young people from hatred. Let us be clear: All public schools in DC are safe places not just for students, but also for parents, families, educators, staff, and community members. Our schools are places of inclusion that value diversity in all its forms, including race, ethnic background, religion, immigration status, disability, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, language, and family’s income level. The diversity throughout the city doesn’t just make us stronger – it is something to celebrate. As educators, it is not only our responsibility to develop students academically, but also to help them grapple with the world around them. It is our hope that we can use these events to have deep and productive conversations about inclusion and respect so that everyone in our schools feels loved, valued, and supported. -

Coping with COVID-19: a Resource Guide for Parents & Families

Meeting Clients' Needs Amidst COVID-19 Updated March 17, 2020 Coping with COVID-19: A Resource Guide for Parents & Families Personal & ● Gabriel Network Office Resources ○ Two week supply of baby toiletries, diapers, & wipes available Family Hygiene ○ Call 301-637-3223 or email [email protected] ○ Time: Walk-In Hours | Wednesday & Friday, 11am-1pm ○ Location: GN Main Office in Crofton, delivery available to Angel Friend Team Nutrition ● Nutritious Shopping List ● Budget Shopping List ● Cleaning and Hygiene Essentials ○ CDC Recommendations ○ Soap, paper towels, sanitizing wipes, latex gloves, hand sanitizer, and hydrogen peroxide ● In the wake of COVID-19, there is more leniency for Clients who are receiving WIC ○ this includes less requirements to come in person to receive &/or maintain benefits ● Capital Area Food Bank Pop Up Food Pantry Location(s) and hours |Tuesday & Saturday 3pm-7pm ○ Giant Parking Lot - 6000 Greenbelt Rd ○ Giant Parking Lot - 7074 Allentown Rd ○ Giant Parking Lot - 10480 Campus Way South ● Every Tuesday, 1pm-3pm: Free Produce & Other Food Items at St. Stephen Baptist Church ○ 5757 Temple Hill Rd, Camp Springs, MD 20748 ○ ● Free Meals for Students in the DMV ○ Free Meals for Students in MD, by County ○ Free Meals for Students in DC ■ Meals will be available for all students every weekday from Monday, March 16-Tuesday, March 31 from 10 am-2 pm at the following sites: School Name Address W a r d Anacostia High School 1601 16th Street SE 8 Ballou High School 3401 4th Street SE 8 Banneker High School 800 Euclid -

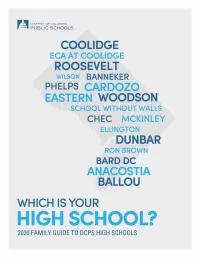

2020 Family Guide to DCPS High Schools 1 What Is the Purpose of This Guide?

2020 Family Guide to DCPS High Schools 1 What is the purpose of this guide? Use this guide as a tool to learn about DCPS high schools, the amazing programs offered, and how your student can enroll. How do I use this guide? Find your neighborhood school: enrolldcps.dc.gov/node/41 enrolldcps.dc.gov/node/16 www.myschooldc.org enrolldcps.dc.gov/node/66 Enrollment typically begins in April of each year. Visit EnrollDCPS.dc.gov for more information. Plan Review the Career Education Pathways available at each DCPS high school on pages 26 and 27 of this guide. Graduate DCPS strives to empower our students on their path to graduation with the tools they need to be successful by creating policies that are supportive, inclusive, and equitable. Learn about our graduation policy here: dcps.dc.gov/prektograduation 2020 Family Guide to DCPS High Schools MY SCHOOL DC LOTTERY The My School DC lottery gives families the opportunity to apply for available seats in early childhood programs for 3- and 4-year-olds, out-of- boundary DCPS schools in grades K-12, citywide schools, DCPS application high schools, and participating charter schools. A single, random lottery is run by My School DC to determine placement of new students at all participating schools.The Office of the State Superintendent of Education oversees the My School DC lottery in collaboration with DCPS, the Public Charter School Board, and participating charter schools. To learn more about the lottery process, visit: www.myschooldc.org 2020 Family Guide to DCPS High Schools 3 Destination school (also feeder pattern school): A middle, high, or education campus school that a student has a right to attend based on the student completing the terminal grade at an elementary or middle school during the previous school year. -

Collegiate Academy 19 Ward 7 Male Friendship

16 Ward 7 Male Friendship PCS - Collegiate Academy 19 Ward 7 Male Friendship PCS - Collegiate Academy 19 Ward 5 Male Friendship PCS - Collegiate Academy 19 Ward 7 Male Friendship PCS - Collegiate Academy 18 Ward 1 Female Phelps Architecture, Construction, and Engineering HS 14 Ward 4 Female Phelps Architecture, Construction, and Engineering HS 17 Ward 5 Male Phelps Architecture, Construction, and Engineering HS 18 Ward 8 Male Friendship PCS - Collegiate Academy 18 Ward 7 Female Friendship PCS - Collegiate Academy 14 Ward 7 Male KIPP DC PCS 19 Ward 6 Female Luke C. Moore HS 16 Ward 7 Female Friendship PCS - Collegiate Academy 17 Ward 7 Male Friendship PCS - Collegiate Academy 14 Ward 7 Female Center City PCS - Trinidad Campus 16 Ward 7 Male Friendship PCS - Collegiate Academy 15 Ward 8 Female Friendship PCS - Collegiate Academy 18 Ward 8 Female Friendship PCS - Collegiate Academy 20 Ward 7 Male Luke C. Moore HS 18 Ward 7 Female Friendship PCS - Collegiate Academy 16 Ward 7 Female Friendship PCS - Collegiate Academy 20 Ward 5 Female Luke C. Moore HS 16 Ward 7 Female Friendship PCS - Collegiate Academy 16 Ward 7 Female Friendship PCS - Collegiate Academy 18 Ward 8 Female Luke C. Moore HS 14 Ward 8 Female Kramer MS 19 Ward 7 Female Friendship PCS - Collegiate Academy 17 Ward 7 Male Phelps Architecture, Construction, and Engineering HS 18 Ward 6 Male Phelps Architecture, Construction, and Engineering HS 17 Ward 5 Male Phelps Architecture, Construction, and Engineering HS 17 Ward 5 Male Luke C. Moore HS 18 Ward 7 Male Friendship PCS - Collegiate Academy 15 Ward 5 Male Phelps Architecture, Construction, and Engineering HS 15 Ward 7 Male Two Rivers PCS 21 Ward 5 Female Luke C.