Arxiv:1912.03988V2 [Cond-Mat.Mes-Hall] 10 Feb 2021 [2, 13–15], Threshold Current Densities Found in Qcls Are [24–29]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quantum Cascade Laser-Based Substance Detection: Approaching the Quantum Noise Limit

Quantum cascade laser-based substance detection: approaching the quantum noise limit Peter C. Kuffnera, Kathryn J. Conroya, Toby K. Boysona, Greg Milford,a Mohamed A. Mabrok,a Abhijit G. Kallapura, Ian R. Petersena, Maria E. Calzadab, Thomas G. Spence,c Kennith P. Kirkbrided and Charles C. Harb a a School of Engineering and Information Technology, University College, The University of New South Wales, Canberra, ACT, 2600, Australia. b Department of Mathematical Sciences, Loyola University New Orleans, New Orleans, LA, 70118, USA. c Department of Chemistry, Loyola University New Orleans, New Orleans, LA, 70118, USA. d Forensic and Data Centres, Australian Federal Police, Weston, ACT, 2611, Australia. ABSTRACT A consortium of researchers at University of New South Wales (UNSW@ADFA), and Loyola University New Orleans (LU NO), together with Australian government security agencies (e.g., Australian Federal Police), are working to develop highly sensitive laser-based forensic sensing strategies applicable to characteristic substances that pose chemical, biological and explosives (CBE) threats. We aim to optimise the potential of these strategies as high-throughput screening tools to detect prohibited and potentially hazardous substances such as those associated with explosives, narcotics and bio-agents. Keywords: Quantum Cascade laser, Trace gas detection, Cavity Ringdown Spectroscopy, IR detection, Foren- sics 1. INTRODUCTION Analysis of bulk organic explosives is a straightforward task for well-equipped forensic laboratories, but it is more difficult to analyse trace amounts of organic explosive residues (particularly in highly-contaminated post- blast samples); this usually requires an elaborate sequence of solvent extraction from swabs and some form of chromatographic or electrophoretic separation. -

New Frontiers in Quantum Cascade Lasers

Physica Scripta INVITED COMMENT Related content - External cavity terahertz quantum cascade New frontiers in quantum cascade lasers: high laser sources based on intra-cavity frequency mixing with 1.2–5.9 THz tuning range performance room temperature terahertz sources Yifan Jiang, Karun Vijayraghavan, Seungyong Jung et al. To cite this article: Mikhail A Belkin and Federico Capasso 2015 Phys. Scr. 90 118002 - Novel InP- and GaSb-based light sources for the near to far infrared Sprengel Stephan, Demmerle Frederic and Amann Markus-Christian - Recent progress in quantum cascade View the article online for updates and enhancements. lasers andapplications Claire Gmachl, Federico Capasso, Deborah L Sivco et al. Recent citations - Optical external efficiency of terahertz quantum cascade laser based on erenkov difference frequency generation A. Hamadou et al - Distributed feedback 2.5-terahertz quantum cascade laser with high-power and single-mode emission Jiawen Luo et al - H. L. Hartnagel and V. P. Sirkeli This content was downloaded from IP address 128.103.224.178 on 26/05/2020 at 19:55 | Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Physica Scripta Phys. Scr. 90 (2015) 118002 (13pp) doi:10.1088/0031-8949/90/11/118002 Invited Comment New frontiers in quantum cascade lasers: high performance room temperature terahertz sources Mikhail A Belkin1 and Federico Capasso2 1 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, USA 2 Harvard University, School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, 29 Oxford St., Cambridge, MA 02138, USA E-mail: [email protected] and [email protected] Received 19 June 2015, revised 25 August 2015 Accepted for publication 11 September 2015 Published 2 October 2015 Abstract In the last decade quantum cascade lasers (QCLs) have become the most widely used source of mid-infrared radiation, finding large scale applications because of their wide tunability and overall high performance. -

High Power Spatial Single-Mode Quantum Cascade Lasers at 8.9 Μm

High power spatial single-mode quantum cascade lasers at 8.9 µm S.Forget, C.Faugeras, J-Y.Bengloan, M.Calligaro, O.Parillaud, M.Giovannini, J.Faist and C.Sirtori Abstract : High performance of InP-based quantum cascade lasers emitting at λ ≈ 9µm are reported. Thick electroplated gold layer was deposited on top of the laser to improve heat dissipation. With one facet high reflection coated, the devices produce a maximum output power of 175mW at 40% duty cycle at room temperature and continuous-wave operation up to 278K. Introduction : Since their first demonstration in 1994 [1], the quantum cascade laser [2] (QCL) is one of the most promising mid- and far-infrared wavelength coherent light source. Its performances in terms of power and operating temperature have been continuously improved and the range of available wavelengths extended. These unipolar lasers are able to cover the wavelength range from 3 to more than 100 µm, and more specifically operate efficiently in the two atmospheric windows (3-5 µm and 8-14µm). Those mid-IR lasers are needed for chemical sensing, free-space optical communications or spectroscopy [3, 4]. These applications require high power, room temperature continuous wave (CW) operation with a diffraction limited laser beam. We report on devices based on InP substrates with a GaInAs/AlInAs active region have proved to be the most efficient material system with regard to the emitted power and CW operation [5]. The main difficulty on the route to high power and CW operation at room temperature is the large amount of heat that must be dissipated in the device. -

Continuous-Wave Room-Temperature Inas Quantum Cascade Laser

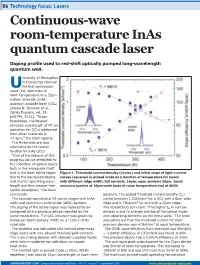

86 Technology focus: Lasers Continuous-wave room-temperature InAs quantum cascade laser Doping profile used to red-shift optically pumped long-wavelength quantum well. niversity of Montpellier in France has claimed Uthe first continuous- wave (cw) operation at room temperature of a 15µm indium arsenide (InAs) quantum cascade laser (QCL) [Alexei N. Baranov et al, Optics Express, vol. 24, p18799, 2016]. “To our knowledge, the longest emission wavelength of RT cw operation for QCLs fabricated from other materials is 12.4µm,” the team reports. The thresholds are also claimed to be the lowest to-date for InAs QCLs. “One of the reasons of this progress can be attributed to the reduction of optical losses both in the waveguide itself and in the laser active region Figure 1. Threshold current density (circles) and initial slope of light-current due to the decreased doping curves (squares) in pulsed mode as a function of temperature for lasers and shorter operating wave- with different ridge width: full symbols, 16µm; open symbols 20µm. Inset: length and thus weaker free emission spectra of 16µm-wide laser at room temperature and at 400K. carrier absorption,” the team comments. perature. The pulsed threshold current density (Jth) The cascade consisted of 55 active stages with InAs varied between 1.22kA/cm2 for a QCL with a 8µm-wide wells and aluminium antimonide (AlSb) barriers. ridge and 0.73kA/cm2 for one with a 20µm ridge. The doping of the active region was reduced by 6x The researchers comment: “The higher Jth in narrow compared with a previous device reported by the devices is due to a larger overlap of the optical mode same researchers. -

Mid-Infrared Gaas/Algaas Quantum Cascade Lasers Technology

Vol. 116 (2009) ACTA PHYSICA POLONICA A Supp. Proceedings of the III National Conference on Nanotechnology NANO 2009 Mid-Infrared GaAs/AlGaAs Quantum Cascade Lasers Technology A. Szerling, P. Karbownik, K. Kosiel, J. Kubacka-Traczyk, E. Pruszyńska-Karbownik, M. Płuska and M. Bugajski Institute of Electron Technology, al. Lotników 32/46, 02-668, Warsaw, Poland The fabrication technology of AlGaAs/GaAs based quantum cascade lasers is reported. The devices operated in pulsed mode at up to 260 K. The peak powers recorded at 77 K were over 1 W for the GaAs/Al0:45Ga0:55As laser without anti-reflection/high-reflection coatings. PACS numbers: 42.55.Px, 85.60.–q, 85.35.Be, 72.80.Ey, 73.61.Ey, 78.66.Fd 1. Introduction for current injection was narrower than the ridge width, which minimizes absorption of generated radiation in di- The quantum cascade lasers (QCLs) are unipolar de- electric layers insulating mesa sidewalls [6, 15]. vices based on intersubband transitions and tunnelling As a rule the relatively high voltages as well as current transport [1, 2]. The GaAs-based QCLs have proved to densities are necessary to polarize QCLs. That indicates be an effective source of laser radiation in mid-infrared demand for low resistance ohmic contacts in order to re- (MIR) as well as far-infrared (FIR) regions. They find duce the device serial resistance. These contacts should application in the gas sensing systems (e.g., for detecting be characterized by thermal stability, low depth of metal CO , NO, CH ) [3], medical diagnostics [4] and environ- 2 4 diffusion into semiconductor layers and lateral uniformity ment monitoring [5]. -

Family Type and Incidence

STRAINED INDIUM ARSENIDE/GALLIUM ARSENIDE LAYER FOR QUANTUM CASCADE LASER DESIGN USING GENETIC ALGORITHM David Mueller Dr. Gregory Triplett, Dissertation Supervisor ABSTRACT Achieving high power, continuous wave, room temperature operation of midinfrared (3-5 um) lasers is diffcult due to the effects of auger recombination in band-to-band designs. Intersubband laser designs such as quantum cascade lasers reduce the effects of recombination, increasing efficiency and have advantages in large tunability of wavelength ranges. Highly efficient quantum cascade laser designs are typically used in lasers designed for >5 um wavelength operation due to the small offset of conduction band energy in lattice matched materials. Some promising material systems have been used to achieve high-power output in the first atmospheric window (3-5 um) but still suffer from low efficiency. Larger ıconduction band offset is attainable through the use of strained materials. However, these material systems have limitations on the traditional (100) crystal orientation due to the large strain and low critical thickness. The necessity for controlled two-dimensional, optical quality layer growth limits the amount of strain incorporation due to defect formation in highly lattice mis-matched layers. The material systems used in this study are GaAs (100) and (111)B, AlGaAs, and (Ga)InAs. In the initial stage of research, I found that pseudomorphic growth of highly strained InAs layers on GaAs (111)B is possible. However, the growth window is very narrow and necessitates precise control over growth temperature and anion overpressure to achieve optical quality layers. As a result, a second stage of research explores the design space made available by this finding by using genetic algorithm based design and simulation of devices with a Schrodinger-Poisson solver. -

Mid-Infrared Quantum Cascade Laser Operable in High Temperature (200°C)

NEW AREAS Mid-infrared Quantum Cascade Laser Operable in High Temperature (200°C) Hiroyuki YOSHINAGA*, Takashi KATO, Yukihiro TSUJI, Hiroki MORI, Jun-ichi HASHIMOTO, and Yasuhiro IGUCHI ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- A quantum cascade laser (QCL) is the most promising semiconductor laser for trace gas sensing in the mid-infrared region due to its excellent features such as a small chip size, high speed modulation, and a narrow linewidth. In practical gas-sensing, QCLs are required to achieve single-mode operation and wide-wavelength tuning without mode-hopping for high-sensitive and multiple gas detection. To obtain the wide tuning range of QCLs, increasing the operation temperature is effective. Therefore, we have developed a distributed feedback (DFB)-QCL that can operate at high temperature by introducing our original strain-compensated core structure and buried-hetero waveguide structure. As a result, we have successfully achieved single-mode operation without mode-hopping between -40ºC and 200ºC under a pulse condition, leading to a wide tuning range of 123 nm with only a single- waveguide QCL. As a future challenge, we will develop a gas-sensing method using the above-mentioned DFB-QCLs as the light source. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Light-Enhanced Incoherence of Electronic Transport in Quantum Cascade Lasers Andrzej Kolek

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Light-enhanced incoherence of electronic transport in quantum cascade lasers Andrzej Kolek Since their invention in the middle of the 1990s, quantum cascade lasers (QCLs) attract increasing theoretical interest stimulated by their widening applications. One of the key theoretical issues is the optimization of electronic transport which in most of these devices is governed by the injection barrier of QCL heterostructure. In the paper, the nonequilibrium Green’s function formalism is used to study electronic transition through the injection barrier as a function of laser feld in the cavity; for the increasing feld, a crossover is observed from the strong coupling regime, in which electronic transport through the barrier is coherent, to the weak coupling regime, in which electronic transport gets incoherent. This crossover is characterized by gain recovery time, τrec, which takes sub-picosecond values for mid-IR QCLs operating at room temperature. This time is also important for the performance of devices under steady-state conditions; the maximum output power is obtained when the fgure of merit, FOM = (g(0)/gth − 1)/gcτrec [g(0) is the linear response gain, gth is the threshold gain needed to compensate all losses, gc is the gain cross-section], reaches maximum. It is shown that the use of this optimization criterion can result in the structures essentially diferent from those which can be obtained when the optimized quantity is the linear response gain, g(0). Quantum cascade laser (QCL) is a semiconductor device used to emit the radiation in the mid-IR or THz fre- quency range. -

New Developments in Gaas-Based Quantum Cascade Lasers

New Developments in GaAs-based Quantum Cascade Lasers Chris Neil Atkins PhD Thesis October 2013 Department of Physics and Astronomy Abstract This thesis presents a study of the design and optimisation of gallium-arsenide-based quantum cascade lasers (QCLs). Traditionally, the optical and electrical performance of these devices has been inferior in comparison to QCLs that are based on the InP material system, due mainly to the limitations imposed on performance by the intrinsic material properties of GaAs. In an attempt to improve the performance of GaAs QCLs, indium-gallium-phosphide and indium-aluminium-phosphide have been used as the waveguide cladding layers in several new QCL designs. These two materials combine low waveguide losses with a high confinement of the laser optical mode, and are easily integrated into typical GaAs QCL structures. Devices containing a double-phonon relaxation active region design have been combined with an InAlP waveguide, with the result being that the lowest threshold currents yet observed for a GaAs-based QCL have been observed - 2.1kA/cm2 and 4.0kA/cm2 at 240K and 300K respectively. Accompanying these low threshold currents however, were large operating voltages approaching 30V at room-temperature and 60V at 80K. These voltages were responsible for a high rate of device failure due to overheating. In an attempt to address this situation, two transitional layer (TL) designs were applied at the QCL GaAs/InAlP interfaces in order to aid electron flow at these points. The addition of the TLs resulted in a lowering of operating voltage by ~12V and 30V at 300K and 240K respectively, however threshold current density increased to 5.1kA/cm2 and 2.7kA/cm2 at the same temperatures. -

Terahertz Quantum Cascade Lasers, Electronics, and Real-Time Imaging

Chapter 27. Terahertz Quantum Cascade, Electronics, and Real-time Imaging Terahertz Quantum Cascade Lasers, Electronics, and Real-time Imaging Academic and Research Staff Professor Qing Hu Postdoctoral Associates Benjamin S. Williams Graduate Students Hans Callebaut, Sushil Kumar, Alan Lee, Qi Qin Introduction THz frequencies (f = 0.3-10 THz) remain one of the most underdeveloped frequency ranges, even though the potential applications in remote sensing and imaging, spectroscopy, and communications are great. This is mainly due to lack of coherent sources with high output power levels. The difficulty to generate THz radiation is because of the so-called "THz gap" in conventional semiconductor devices, which falls between two other frequency ranges in which solid-state sources have been well developed. One is the microwave and millimeter-wave frequency range, and the other is the near-infrared and optical frequency range. Semiconductor electronic devices that utilize oscillating conduction current J (such as transistors, Gunn oscillators, Schottky-diode frequency multipliers, and photomixers) are limited by the transit time and parasitic RC time constants. Consequently, the power level of these electronic devices decreases rapidly as the frequency f increases above 1 THz. In contrast to the electronic devices, photonic or quantum electronic devices (such as laser diodes) generate radiation by ∂p oscillating bounded dipoles (which give rise to an oscillating displacement current ). As a result, they ∂ t are not limited by the transient time and/or the RC time constant. However, for conventional bi-polar laser diodes, they are limited to frequencies above that corresponds to the semiconductor energy gap, which is higher than 10 THz even for narrow-gap lead-salt materials. -

Quantum Cascade Laser User's Manual

QUANTUM CASCADE LASER USER’S MANUAL Version number 3.0 c 2012 ALPES LASERS SA This page intentionally left blank. COPYRIGHT INFORMATION This manual can be copied and distributed under the following conditions: the work must be attributed in the manner specified by the author or licensor, and cannot be altered or transformed. WARRANTY 1. The customer must control the incoming deliveries and inform ALPES LASERS about incomplete shipments or defective goods within 30 days after delivery. ALPES LASERS warrants that the products respect the performance set forth in the quotation, provided that the product is used according to ALPES LASERS recommendations described in the datasheet included in the shipment. 2. Defective products will be replaced during the 2 years following delivery. 3. All other claims such as purchase refund, product reconditioning or damage of any nature, be it direct, indirect or consequential, are expressly ousted. 4. The customer is aware of laser products being devices with a statistical rate of failure. Depending on the use made of this product, it is the customer’s respon- sibility to use caution, redundancy and appropriate technical measurement to ensure the final product’s proper operation. 5. In case of discrepancy between the manual and terms written in the order con- firmation, the order confirmation prevails. CONTACT INFORMATION Max-Meuron 1-3 C.P. 1766 CH-2001 Neuchâtel Switzerland Telephone: +41 32 729 9510 Fax: +41 32 721 3619 Email: [email protected] Web site: http://www.alpeslasers.ch c 2012 SA iii This page intentionally left blank. Preface This manual is a reference tool for personnel using ALPES LASERS QCLs and elec- tronic equipment. -

Quantum Cascade Laser Code Prediction

Quantum Cascade Laser Code Prediction Dr. Christopher Baird Submillimeter-Wave Technology Laboratory University of Massachusetts Lowell February, 2009 OUTLINE I. Current Work A. Introduction & Code Structure Overview B. Finding the Wave Functions C. Finding the Scattering Times D. Finding the Populations and Gain II. Future Work WHAT IS A QCL? A Quantum Cascade Laser (QCL) is a next-generation device that uses electron transitions between man-made quantum well levels, as opposed to traditional lasers that use transitions between atomic levels. WHAT IS A QCL? Quantum wells are built by stacking up alternating layers of semiconductors with thicknesses of only a few atoms. WHAT IS A QCL? Molecular Beam Epitaxy (MBE) system used at UMass to build QCL's layer by layer. HOW DOES A QCL WORK? E AlGaAs GaAs AlGaAs E (z) c Ψ (z) Conduction V(z) Φ(z) n Band E E (z) n F Φ(z) E (z) Φ(z) E (z) g v Valence Band -eΔΦ app z ΔΦ : Externally applied voltage drop E : Energies of possible quantum states applied n Φ(z): Built-in potential E (z) : Fermi energies F E (z) : Conduction band edge energy in bulk E (z) : Valence band edge energy in bulk c v V(z) : Effective conduction band edge energy E (z) : Band-gap energies in bulk g Ψ (z): Wave functions n HOW DOES A QCL WORK? By properly adjusting the layer thicknesses, the quantum states are fine-tuned until lasing occurs. The electrons cascade down through the quantum states like a waterfall, emitting laser radiation at each drop.