Esarbica Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oath Ceremonies in Spain and New Spain in the 18Th Century: a Comparative Study of Rituals and Iconography* Historia Crítica, No

Historia Crítica ISSN: 0121-1617 Departamento de Historia, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de los Andes Rodríguez Moya, Inmaculada Oath Ceremonies in Spain and New Spain in the 18th century: A Comparative Study of Rituals and Iconography* Historia Crítica, no. 66, 2017, October-December, pp. 3-24 Departamento de Historia, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de los Andes DOI: https://doi.org/10.7440/histcrit66.2017.01 Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=81154857002 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative 3 Oath Ceremonies in Spain and New Spain in the 18th Century: A Comparative Study of Rituals and Iconography❧ Inmaculada Rodríguez Moya Universitat Jaume I, Spain doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.7440/histcrit66.2017.01 Reception date: March 02, 2016/Acceptance: September 23, 2016/ Modification: October 13, 2016 How to cite: Rodríguez Moya, Inmaculada. “Oath Ceremonies in Spain and New Spain in the 18th century: A Comparative Study of Rituals and Iconography”. Historia Crítica n. ° 66 (2017): 3-24, doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.7440/histcrit66.2017.01 Abstract: This paper will focus on a comparative study of the royal oath ceremonies in Spain and New Spain starting with the 16th century, when the ritual was established, to later consider some examples from the 18th century. A process of consolidating a Latin American and Hispanic identity began in the 17th century and was reflected in religious and political festivals everywhere. -

List 283 | October 2014

Stephen Album Rare Coins Specializing in Islamic, Indian & Oriental Numismatics P.O. Box 7386, Santa Rosa, CA. 95407, U.S.A. 283 Telephone 707-539-2120 — Fax 707-539-3348 [email protected] Catalog price $5.00 www.stevealbum.com 137187. SAFAVID: Muhammad Khudabandah, 1578-1588, AV ½ OCTOBER 2014 mithqal (2.31g), Mashhad, AH[9]85, A-2616.2, type A, with epithet imam reza, some flatness, some (removable) dirt Gold Coins on obverse, VF, R, ex. Richard Accola collection $350 137186. SAFAVID: Muhammad Khudabandah, 1578-1588, AV mithqal (4.59g), Qazwin, AH[9]89, A-2617.2, type B, some weakness Ancient Gold towards the rim, VF, R, ex. Richard Accola collection $450 137190. SAFAVID: Sultan Husayn, 1694-1722, AV ashrafi (3.47g), Mashhad, AH1130, A-2669E, local design, used only at Mashhad, 138883. ROMAN EMPIRE: Valentinian I, 364-375 AD, AV solidus the site of the tomb of the 8th Shi’ite Imam, ‘Ali b. Musa al-Reza, (4.47g), Thessalonica, bust facing right, pearl-diademed, no weakness, VF, RRR, ex. Richard Accola collection $1,000 draped & cuirassed / Valentinian & Valens seated, holding The obverse text is hoseyn kalb-e astan-e ‘ali, “Husayn, dog at together a globe, Victory behind with outspread wings, the doorstep of ‘Ali.,” with additional royal text in the obverse SMTES below, very tiny rim nick, beautiful bold strike, margin, not found on the standard ashrafis of type #2669. choice EF, R $1,200 By far the most common variety of this type is of the Trier 137217. AFSHARID: Shahrukh, 2nd reign, 1750-1755, AV mohur mint, with Constantinople also relatively common. -

Journal of the 79Th Diocesan Convention

EPISCOPAL DIOCESE OF ROCHESTER 2010 JOURNAL OF CONVENTION AND THE CONSTITUTION AND CANONS Journal of the Proceedings of the Seventy-Ninth Annual Convention of the EPISCOPAL DIOCESE OF ROCHESTER held at The Hyatt Regency Rochester Rochester, New York November 5 & 6, 2010 together with the Elected Bodies, Clergy Canonically Resident, Diocesan Reports, Parochial Statistics Constitution and Canons 2010 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part One -- Organization Pages Diocesan Organization 4 Districts of the Diocese 13 Clergy in Order of Canonical Residence 15 Addresses of Lay Members and Elected Bodies 21 Parishes and Missions 23 Part Two -- Annual Diocesan Convention Clerical and Lay Deputies 26 Bishop’s Address 31 Official Acts of the Bishop 38 Bishop’s Discretionary Fund 42 Licenses 44 Journal of Convention 52 Diocesan Budget 70 Clergy and Lay Salary Scales 78 Part Three -- Reports Report of Commission on Ministry 84 Diocesan Council Minutes 85 Standing Committee Report 90 Report of the Trustees 92 Reports of Other Departments and Committees 93 Diocesan Audit 120 Part Four -- Parochial Statistics Parochial Statistics 137 Constitution and Canons 141 3 PART ONE ORGANIZATION 4 THE EPISCOPAL DIOCESE OF ROCHESTER 935 East Avenue Rochester, New York 14607 Telephone: 585-473-2977 Fax: 585-473-3195 or 585-473-5414 OFFICERS Bishop of the Diocese The Rt. Rev. Prince G. Singh Chancellor Registrar Philip R. Fileri, Esq. Ms. Nancy Bell Harter, Secrest &Emery, LLP 6 Goldenhill Lane 1600 Bausch & Lomb Place Brockport, NY 14420 Rochester, NY 14607 585-637-0428 585-232-6500 e-mail: [email protected] FAX: 585-232-2152 e-mail: [email protected] Assistant Registrar Ms. -

Towards an Assessment of Fresh Expressions of Church in Acsa

TOWARDS AN ASSESSMENT OF FRESH EXPRESSIONS OF CHURCH IN ACSA (THE ANGLICAN CHURCH OF SOUTHERN AFRICA) THROUGH AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY OF THE COMMUNITY SUPPER AT ST PETER’S CHURCH IN MOWBRAY, CAPE TOWN REVD BENJAMIN JAMES ALDOUS DISSERTATION PRESENTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTORAL PHILOSOPHY IN THEOLOGY (PRACTICAL THEOLOGY) IN THE FACULTY OF THEOLOGY AT THE UNIVERSITY OF STELLENBOSCH APRIL 2019 SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR IAN NELL Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: April 2019 Copyright © 2019 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ABSTRACT Fresh Expressions of Church is a growing mission shaped response to the decline of mainline churches in the West. Academic reflection on the Fresh Expressions movement in the UK and the global North has begun to flourish. No such reflection, of any scope, exists in the South African context. This research asks if the Fresh Expressions of Church movement is an appropriate response to decline and church planting initiatives in the Anglican Church in South Africa. It also seeks to ask what an authentic contextual Fresh Expression of Church might look like. Are existing Fresh Expression of Church authentic responses to church planting in a postcolonial and post-Apartheid terrain? Following the work of the ecclesiology and ethnography network the author presents an ethnographic study of The Community Supper at St Peter’s Mowbray, Cape Town. -

Solidarity and Mediation in the French Stream Of

SOLIDARITY AND MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Timothy R. Gabrielli Dayton, Ohio December 2014 SOLIDARITY AND MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Name: Gabrielli, Timothy R. APPROVED BY: _________________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Faculty Advisor _________________________________________ Dennis M. Doyle, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Anthony J. Godzieba, Ph.D. Outside Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Vincent J. Miller, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Daniel S. Thompson, Ph.D. Chairperson ii © Copyright by Timothy R. Gabrielli All rights reserved 2014 iii ABSTRACT SOLIDARITY MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Name: Gabrielli, Timothy R. University of Dayton Advisor: William L. Portier, Ph.D. In its analysis of mystical body of Christ theology in the twentieth century, this dissertation identifies three major streams of mystical body theology operative in the early part of the century: the Roman, the German-Romantic, and the French-Social- Liturgical. Delineating these three streams of mystical body theology sheds light on the diversity of scholarly positions concerning the heritage of mystical body theology, on its mid twentieth-century recession, as well as on Pope Pius XII’s 1943 encyclical, Mystici Corporis Christi, which enshrined “mystical body of Christ” in Catholic magisterial teaching. Further, it links the work of Virgil Michel and Louis-Marie Chauvet, two scholars remote from each other on several fronts, in the long, winding French stream. -

The Anglican Diocese of Natal a Saga of Division and Healing the New Cathedral of the Holy Nativity in Pietermaritzburg Was Dedicated in November of This Year

43 The Anglican Diocese of Natal A Saga of Division and Healing The new cathedral of the Holy Nativity in Pietermaritzburg was dedicated in November of this year. The vast cylinder of red brick stands next to the smaller neo-gothic shale and slate church of St Peter which was consecrated in 1857. The period of 124 years between the two events carries a tale of division which in its lurid details is as ugly as the subsequent process of reunion has been fruitful. Now follows the saga of division and healing. In 1857 when St Peter's was first opened for worship there was already tension between the dean and bishop, though it was still below the surface. The private correspondence of Bishop John William Colenso shows that he would have preferred his former college friend, the Reverend T. Patterson Ferguson, to be dean. Dean James Green on the other hand was writing to Metopolitan Robert Gray of Cape Town and complaining about Colenso's methods of administering the diocese. The disagreements between the two men became public during the following year, 1858. Dean Green, together with Canon John David Jenkins, walked out. of the cathedral when they heard Colenso preaching about the theology of the eucharist. Although they later returned, Colenso had to administer holy communion unassisted. Later in the year the same men, together with Archdeacon C.F. Mackenzie and the Reverend Robert Robertson, walked out of a conference of clergy and laity of the diocese. On each occasion the dean and bishop were differing on points of detail. -

Denis Hurley Association

Support the Denis Hurley Association The Denis Hurley Association is a registered charity based in Britain. Our aim is to keep the vision of Denis Hurley alive and to promote and raise funds for the Denis Hurley Centre in Durban, South Africa. All money raised by the Denis Hurley Association goes Denis Hurley dedicated his life to the directly to the Denis Hurley Centre. You can become a poor, the marginalised, the abandoned supporter by donating to the Denis Hurley Association. and the downtrodden. He fought Donations can be made by: Denis Hurley tirelessly for an end to apartheid, and Cheque Please make cheques payable to Association for equality among all human beings. “Denis Hurley Association” He truly lived the words of the Oblate Bank Transfer Bank name: The Co-operative Bank Founder, St Eugene de Mazenod, Account Name: Denis Hurley Association who called us to lead people to be Account Number: 65456699 Sort Code: 08-92-99 “human beings first of all, then Online Donations Christians, then saints.” https://mydonate.bt.com/charities/denishurleyassociation Please e-mail [email protected] if you send an online bank transfer, so we can properly acknowledge your contribution and keep you up to date on the project. Archbishop Denis Hurley OMI PATRONS Contact us at: “Guardian of the Light” Bishop David Konstant Denis Hurley Association, Cardinal Cormac Murphy-O’Connor Denis Hurley House, 14 Quex Road, Bishop Maurice Taylor London NW6 4PL Fr Ray Warren OMI [email protected] Archbishop Denis Hurley had a vision of the Baroness Shirley Williams www.denishurleyassociation.org.uk church as a “community serving humanity”. -

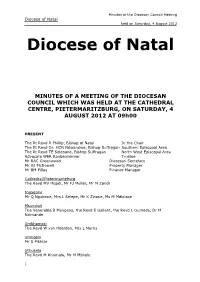

Diocese of Natal Held on Saturday, 4 August 2012

Minutes of the Diocesan Council Meeting Diocese of Natal held on Saturday, 4 August 2012 Diocese of Natal MINUTES OF A MEETING OF THE DIOCESAN COUNCIL WHICH WAS HELD AT THE CATHEDRAL CENTRE, PIETERMARITZBURG, ON SATURDAY, 4 AUGUST 2012 AT 09h00 PRESENT The Rt Revd R Phillip, Bishop of Natal In the Chair The Rt Revd Dr. HCN Ndwandwe, Bishop Suffragan Southern Episcopal Area The Rt Revd TE Seleoane, Bishop Suffragan North West Episcopal Area Advocate WER Raubenheimer Trustee Mr RAC Greenwood Diocesan Secretary Mr GJ McDowell Property Manager Mr BM Pillay Finance Manager Cathedral/Pietermaritzburg The Revd MV Mqadi, Mr FJ Muller, Mr M Zondi Ingagane Mr Q Ngubane, Mrs L Selepe, Mr K Zwane, Ms M Mdlalose Msunduzi The Venerable B Mangena, the Revd E Gallant, the Revd L Gumede, Dr M Nzimande Umkhomazi The Revd W van Heerden, Mrs L Morris Umngeni Mr S Mkhize Uthukela The Revd M Khumalo, Mr M Mbhele 1 Minutes of the Diocesan Council Meeting Diocese of Natal held on Saturday, 4 August 2012 Durban The Venerable GM Laban, Mr D Trudgeon Durban Ridge The Venerable NM Msimango, the Revd T Tembe, Mr W Abrahams Durban South The Venerable WP Dludla, the Revd M Zondi, Mr W Joshua, Mr A Mvelase, the Revd M Zondi Lovu The Revd M Wishart, the Revd M Silva, Mr A Cooper North Coast The Venerable PC Houston, the Revd C Mahaye, Ms P Nzuza 2 Minutes of the Diocesan Council Meeting Diocese of Natal held on Saturday, 4 August 2012 North Durban The Venerable M Skevington Pinetown The Venerable Dr AE Warmback, the Revd G Thompson, Ms T Maseatile, Mr E Pines, Mr S Zondi Umzimkhulu The Venerable P Nene, Ms L Cebisa Diocesan Committees The Revd Canon Dr P Wyngaard, The Revd GA Thompson, Mrs R Phillip, Ms Z Mbongwe, Mrs N Vilakazi, Mr K Dube, Ms Z Hlatshwayo 1. -

The Story of Father EDWARD MNGANGA the First Zulu Catholic Priest

1 THE ABUSE OF A GENIUS EDWARD MULLER KECE MNGANGA -1872-1945 The Story of Father EDWARD MNGANGA The First Zulu Catholic Priest By T. S. N. GQUBULE 2 INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I was at the home of my daughter, Phumla, and her husband Tutu Mnganga when Tutu told me that there was a Roman Catholic Priest in his family who had studied in Rome. I was interested because I had written a Ph.D thesis on the Theological Education of Africans in the Anglican, Congregational, Methodist and Presbyterian Ministers in South Africa during the period 1860-1960. I visited the offices of the Roman Catholic Church in Durban where that I contact Bishop Mlungisi Pius Dlungwane of the Diocese of Mariannhill. The Bishop welcomed Tutu Mnganga and myself warmly and introduced us to Father Raphael Mahlangu, a lecturer at St. Joseph’s Scholasticate, Cedara outside Pietermaritzburg. Father Mahlangu gave me valuable information and many pictures which are included in this book as well as articles which appeared in a Zulu Newspaper, “UmAfrika”. Many of these were written after the death of Edward Mnganga in 1945. I am very grateful to Professor Philippe Denis of the University of KZN who passed on to me the unpublished Ph.D. thesis of G. S. Mukuka from which I have learnt a lot about the life and work of Father Edward Mnganga. Later Mukuka’s thesis appeared in book form under the title “The Other Side of The Story” . The book details the experiences of the Black clergy in the Catholic Church in South Africa (1898-1976) and is published by Cluster Publications (2008). -

In This Issue …

Marist Brothers – Irmãos Maristas Province of Southern Africa – Província da África Austral NEWSLETTER 2017 May - June Vol.2 #6 IN THIS ISSUE … Reception of our First-Year Novices Message from Brother Norbert Birthdays “Senderos” Programme in Manziana Br Adrien Beaudoin (99) RIP Creative Projects by the “Blue Marists” in Aleppo Photo Time! Pope Francis in a Private Audience with Br Emili Meeting of Marist Bursars from around the World Gems from Brother Emili A First Trip to Rome Post-Truth Intentions for our Prayers Commemorating 150 years of the Brothers in Africa Brother Jude Pieterse receives the BONUM COMUNE AWARD New Icon represents our three-year preparation for the Bicentenary 1 OFFICIAL RECEPTION OF FIRST-YEAR NOVICES New Novices with Br António Pisco, Br Emmanuel Mwanalirenji and Br Norbert Mwila fter a long wait of nearly two months, the novices- to-be finally arrived at the novitiate. We were in high spirits and they too were contented to start the A novitiate. They were officially accepted on 1 April 2017 in a vibrant and well-thought-out ceremony. Our Chaplain, Father Petros, led the Eucharistic celebration at 11h 00. During the celebration, the Master of novices, Brother Emmanuel, exhorted to them to be good Marist Novices and to embrace the formation process. The provincial Brother Norbert challenged them to be the main artisans of their own formation as they journey towards holiness. Thereafter we had a special meal and the 2nd-year novices performed a number of activities. As they start the canonical year we wish the 1st-years the graces they need from above. -

Places of Prayer in the Monastery of Batalha Places of Prayer in the Monastery of Batalha 2 Places of Prayer in the Monastery of Batalha

PLACES OF PRAYER IN THE MONASTERY OF BATALHA PLACES OF PRAYER IN THE MONASTERY OF BATALHA 2 PLACES OF PRAYER IN THE MONASTERY OF BATALHA CONTENTS 5 Introduction 9 I. The old Convent of São Domingos da Batalha 9 I.1. The building and its grounds 17 I. 2. The keeping and marking of time 21 II. Cloistered life 21 II.1. The conventual community and daily life 23 II.2. Prayer and preaching: devotion and study in a male Dominican community 25 II.3. Liturgical chant 29 III. The first church: Santa Maria-a-Velha 33 IV. On the temple’s threshold: imagery of the sacred 37 V. Dominican devotion and spirituality 41 VI. The church 42 VI.1. The high chapel 46 VI.1.1. Wood carvings 49 VI.1.2. Sculptures 50 VI.2. The side chapels 54 VI.2.1. Wood carvings 56 VI.3. The altar of Jesus Abbreviations of the authors’ names 67 VII. The sacristy APA – Ana Paula Abrantes 68 VII.1. Wood carvings and furniture BFT – Begoña Farré Torras 71 VIII. The cloister, chapter, refectory, dormitories and the retreat at Várzea HN – Hermínio Nunes 77 IX. The Mass for the Dead MJPC – Maria João Pereira Coutinho MP – Milton Pacheco 79 IX.1. The Founder‘s Chapel PR – Pedro Redol 83 IX.2. Proceeds from the chapels and the administering of worship RQ – Rita Quina 87 X. Popular Devotion: St. Antão, the infante Fernando and King João II RS – Rita Seco 93 Catalogue SAG – Saul António Gomes SF – Sílvia Ferreira 143 Bibliography SRCV – Sandra Renata Carreira Vieira 149 Credits INTRODUCTION 5 INTRODUCTION The Monastery of Santa Maria da Vitória, a veritable opus maius in the dark years of the First Republic, and more precisely in 1921, of artistic patronage during the first generations of the Avis dynasty, made peace, through the transfer of the remains of the unknown deserved the constant praise it was afforded year after year, century soldiers killed in the Great War of 1914-1918 to its chapter room, after century, by the generations who built it and by those who with their history and homeland. -

Reviewed by Bobby Godsell

THE JOURNAL OF THE HELEN SUZMAN FOUNDATION | ISSUE 69 | JUNE 2013 Bobby Godsell Bobby Godsell is a BOOK REVIEW distinguished South African businessman. He is currently the chairman of Business Denis Hurley Leadership South Africa, and a member of the National Truth to Power Planning Commission. The American sociologist Peter Berger has produced, more or less, in every decade of his adult life an important book about religion. On the cover of one of these he put a picture of the place of great Italian beauty, Lake Como. Berger asserted that this place of beauty was reason enough to accept that our world had a creator whose design for our universe and our lives was good. I would argue that the lives of some people – saints in the broadest, oldest and most inclusive sense – is reason enough to believe that this creator continues to love our crazy, troubled world and inspire those who love him to act in it. One such saintly person is Denis Hurley. Paddy Kearney’s abridged story of his life tells a remarkable story of: where this man of God began his journey, what he became, his achievements, his failures and most, of all, of that deep and abiding love which inhabited his heart and character until the moment of his death. Hurley began his journey in South Africa as the son of a pretty poor immigrant family (from Ireland). His father was a lighthouse keeper leading therefore, a life that was itinerant, isolated and lonely. Hurley’s family circumstances required an active search for quality schooling, DENIS HURLEY: leading to time spent first in Ireland and Rome in preparation for ordination as a TRUTH TO POWER priest.