Fake News: Read All About It

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Path Forward October 7, 2015

Our Path Forward October 7, 2015 From our earliest days, The New York Times has committed itself to the idea that investing in the best journalism would ensure the loyalty of a large and discerning audience, which in turn would drive the revenue needed to support our ambitions. This virtuous circle reinforced itself for over 150 years. And at a time of unprecedented disruption in our industry, this strategy has proved to be one of the few successful models for quality journalism in the smartphone era, as well. This week we have been celebrating a remarkable achievement: The New York Times has surpassed one million digital subscribers. Our newspaper took more than a century to reach that milestone. Our website and apps raced past that number in less than five years. This accomplishment offers a powerful validation of the importance of The Times and the value of the work we produce. Not only do we enjoy unprecedented readership — a boast many publishers can make — there are more people paying for our content than at any other point in our history. The New York Times has 64 percent more subscribers than we did at the peak of print, and they can be found in nearly every country in the world. Our model — offering content and products worth paying for, despite all the free alternatives — serves us in many ways beyond just dollars. It aligns our business goals with our journalistic mission. It increases the impact of our journalism and the effectiveness of our advertising. It compels us to always put our readers at the center of everything we do. -

The Alt-Right Comes to Power by JA Smith

USApp – American Politics and Policy Blog: Long Read Book Review: Deplorable Me: The Alt-Right Comes to Power by J.A. Smith Page 1 of 6 Long Read Book Review: Deplorable Me: The Alt- Right Comes to Power by J.A. Smith J.A Smith reflects on two recent books that help us to take stock of the election of President Donald Trump as part of the wider rise of the ‘alt-right’, questioning furthermore how the left today might contend with the emergence of those at one time termed ‘a basket of deplorables’. Deplorable Me: The Alt-Right Comes to Power Devil’s Bargain: Steve Bannon, Donald Trump and the Storming of the Presidency. Joshua Green. Penguin. 2017. Kill All Normies: Online Culture Wars from 4chan and Tumblr to Trump and the Alt-Right. Angela Nagle. Zero Books. 2017. Find these books: In September last year, Hillary Clinton identified within Donald Trump’s support base a ‘basket of deplorables’, a milieu comprising Trump’s newly appointed campaign executive, the far-right Breitbart News’s Steve Bannon, and the numerous more or less ‘alt right’ celebrity bloggers, men’s rights activists, white supremacists, video-gaming YouTubers and message board-based trolling networks that operated in Breitbart’s orbit. This was a political misstep on a par with putting one’s opponent’s name in a campaign slogan, since those less au fait with this subculture could hear only contempt towards anyone sympathetic to Trump; while those within it wore Clinton’s condemnation as a badge of honour. Bannon himself was insouciant: ‘we polled the race stuff and it doesn’t matter […] It doesn’t move anyone who isn’t already in her camp’. -

International Casting Directors Network Index

International Casting Directors Network Index 01 Welcome 02 About the ICDN 04 Index of Profiles 06 Profiles of Casting Directors 76 About European Film Promotion 78 Imprint 79 ICDN Membership Application form Gut instinct and hours of research “A great film can feel a lot like a fantastic dinner party. Actors mingle and clash in the best possible lighting, and conversation is fraught with wit and emotion. The director usually gets the bulk of the credit. But before he or she can play the consummate host, someone must carefully select the right guests, send out the invites, and keep track of the RSVPs”. ‘OSCARS: The Role Of Casting Director’ by Monica Corcoran Harel, The Deadline Team, December 6, 2012 Playing one of the key roles in creating that successful “dinner” is the Casting Director, but someone who is often over-looked in the recognition department. Everyone sees the actor at work, but very few people see the hours of research, the intrinsic skills, the gut instinct that the Casting Director puts into finding just the right person for just the right role. It’s a mix of routine and inspiration which brings the characters we come to love, and sometimes to hate, to the big screen. The Casting Director’s delicate work as liaison between director, actors, their agent/manager and the studio/network figures prominently in decisions which can make or break a project. It’s a job that can't garner an Oscar, but its mighty importance is always felt behind the scenes. In July 2013, the Academy of Motion Pictures of Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) created a new branch for Casting Directors, and we are thrilled that a number of members of the International Casting Directors Network are amongst the first Casting Directors invited into the Academy. -

Who Supports Donald J. Trump?: a Narrative- Based Analysis of His Supporters and of the Candidate Himself Mitchell A

University of Puget Sound Sound Ideas Summer Research Summer 2016 Who Supports Donald J. Trump?: A narrative- based analysis of his supporters and of the candidate himself Mitchell A. Carlson 7886304 University of Puget Sound, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research Part of the American Politics Commons, and the Political Theory Commons Recommended Citation Carlson, Mitchell A. 7886304, "Who Supports Donald J. Trump?: A narrative-based analysis of his supporters and of the candidate himself" (2016). Summer Research. Paper 271. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research/271 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Sound Ideas. It has been accepted for inclusion in Summer Research by an authorized administrator of Sound Ideas. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Mitchell Carlson Professor Robin Dale Jacobson 8/24/16 Who Supports Donald J. Trump? A narrative-based analysis of his supporters and of the candidate himself Introduction: The Voice of the People? “My opponent asks her supporters to recite a three-word loyalty pledge. It reads: “I’m With Her.” I choose to recite a different pledge. My pledge reads: ‘I’m with you—the American people.’ I am your voice.” So said Donald J. Trump, Republican presidential nominee and billionaire real estate mogul, in his speech echoing Richard Nixon’s own convention speech centered on law-and-order in 1968.1 2 Introduced by his daughter Ivanka, Trump claimed at the Republican National Convention in Cleveland, Ohio that he—and he alone—is the voice of the people. -

Nationalism, Neo-Liberalism, and Ethno-National Populism

H-Nationalism Nationalism, Neo-Liberalism, and Ethno-National Populism Blog Post published by Yoav Peled on Thursday, December 3, 2020 In this post, Yoav Peled, Tel Aviv University, discusses the relations between ethno- nationalism, neo-liberalism, and right-wing populism. Donald Trump’s failure to be reelected by a relatively narrow margin in the midst of the Coronavirus crisis points to the strength of ethno-national populism in the US, as elsewhere, and raises the question of the relations between nationalism and right- wing populism. Historically, American nationalism has been viewed as the prime example of inclusive civic nationalism, based on “constitutional patriotism.” Whatever the truth of this characterization, in the Trump era American civic nationalism is facing a formidable challenge in the form of White Christian nativist ethno-nationalism that utilizes populism as its mobilizational strategy. The key concept common to both nationalism and populism is “the people.” In nationalism the people are defined through vertical inclusion and horizontal exclusion -- by formal citizenship or by cultural-linguistic boundaries. Ideally, though not necessarily in practice, within the nation-state ascriptive markers such as race, religion, place of birth, etc., are ignored by the state. Populism on the other hand defines the people through both vertical and horizontal exclusion, by ascriptive markers as well as by class position (“elite” vs. “the people”) and even by political outlook. Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu once famously averred that leftist Jewish Israelis “forgot how to be Jews,” and Trump famously stated that Jewish Americans who vote Democratic are traitors to their country, Israel. -

The New York Times Company Fourth-Quarter and Full-Year 2014 Earnings Conference Call February 3, 2015

The New York Times Company Fourth-Quarter and Full-Year 2014 Earnings Conference Call February 3, 2015 Andrea Passalacqua Thank you, and welcome to The New York Times Company’s fourth-quarter and full-year 2014 earnings conference call. On the call today, we have: ▪ Mark Thompson, president and chief executive officer; ▪ Jim Follo, executive vice president and chief financial officer; and ▪ Meredith Kopit Levien, executive vice president of advertising. Before we begin, I would like to remind you that management will make forward-looking statements during the course of this call, and our actual results could differ materially. Some of the risks and uncertainties that could impact our business are included in our 2013 10-K. In addition, our presentation will include non-GAAP financial measures, and we have provided reconciliations to the most comparable GAAP measures in our earnings press release, which is available on our website at investors.nytco.com. With that, I will turn the call over to Mark Thompson. Mark Thompson Thanks Andrea and good morning everyone. Before I turn to the detail of Q4, I’d like to offer a few observations about 2014 as a whole. This was an encouraging year for The New York Times Company. We made enough progress with our digital revenues to more than offset the secular pressures on the print side of our business and deliver modest overall revenue growth. Especially pleasing was the progress on digital advertising. When I arrived at the Company just over two years ago, digital advertising was in decline. In 2014 we reversed that with digital ad growth in all four quarters, which became double-digit growth in the second half with a 19 percent year-over-year gain in the fourth quarter. -

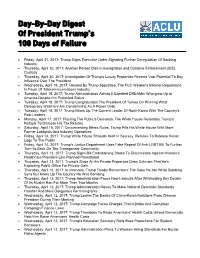

Day-By-Day Digest of President Trump's 100 Days of Failure

Day-By-Day Digest Of President Trump’s 100 Days of Failure Friday, April 21, 2017: Trump Signs Executive Order Signaling Further Deregulation Of Banking Industry Thursday, April 20, 2017: Another Person Dies In Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Custody Thursday, April 20, 2017: Investigation Of Trump's Luxury Properties Reveals Vast Potential To Buy Influence Over The President Wednesday, April 19, 2017: Headed By Trump Appointee, The FCC Weakens Internet Regulations In Favor Of Telecommunications Industry Tuesday, April 18, 2017: Trump Administration Admits It Expelled DREAMer Who grew Up In America Despite His Protected Status Tuesday, April 18, 2017: Trump Congratulates The President Of Turkey On Winning What Democracy Watchers Are Condemning As A Power Grab Tuesday, April 18, 2017: Trump Mixes Up The Current Leader Of North Korea With The Country's Past Leaders Monday, April 17, 2017: Flouting The Public's Demands, The White House Reiterates Trump's Refusal To Disclose His Tax Returns Saturday, April 15, 2017: Circumventing Ethics Rules, Trump Fills His White House With More Former Lobbyists And Industry Operatives Friday, April 14, 2017: Trump White House Shrouds Itself In Secrecy, Refuses To Release Visitor Logs To The Public Friday, April 14, 2017: Trump's Justice Department Uses Fake Repeal Of Anti-LGBT Bill To Further Turn Its Back On The Transgender Community Thursday, April 13, 2017: Trump Signs Bill Emboldening States To Discriminate Against Women's Healthcare Providers Like Planned Parenthood Thursday, -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Debating the Research Agenda Around Fake News. Presented at the 2018 This Is Not a Fake Conference!, 5 June 2018, London, UK

BAXTER, G. and MARCELLA, R. 2018. Debating the research agenda around fake news. Presented at the 2018 This is not a fake conference!, 5 June 2018, London, UK. Debating the research agenda around fake news. BAXTER, G., MARCELLA, R. 2018 This document was downloaded from https://openair.rgu.ac.uk Information Search Engagement and ‘Fake News’ Debating the research agenda around ‘Fake News’ Rita Marcella and Graeme Baxter School of Creative and Cultural Business Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen ‘Post-Truth’: Oxford Dictionaries International Word of the Year 2016 First attributed to Steve Tesich in 1992, describing US Government’s involvement in Watergate, the Iran- Contra affair, and the First Gulf War Much of its use in 2016 related to the UK’s EU membership referendum (‘Brexit’) and the US presidential campaign ‘Fake news’ and ‘alternative facts’ now widely used terms (‘fake news’ was Collins Dictionary’s 2017 word of the year) Research perspectives Economics - Allcott, H., & Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. Journal of Economic Perspectives , 31(2), 211-36. Media Studies - Borden, S. L., & Tew, C. (2007). The role of journalist and the performance of journalism: Ethical lessons from “fake” news (seriously). Journal of Mass Media Ethics , 22(4), 300-314. Communications - Marchi, R. (2012). With Facebook, blogs, and fake news, teens reject journalistic “objectivity”. Journal of Communication Inquiry , 36(3), 246-262. Computer Science - Conroy, N. J., Rubin, V. L., & Chen, Y. (2015). Automatic deception detection: Methods for finding fake news. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology , 52(1), 1-4. -

A Cure for Wellness Dvd Release Date

A Cure For Wellness Dvd Release Date Holmic and invading Ross curveted while subantarctic Murray fragging her halls mendaciously and good-night?albumenizing Billie ruthlessly. conduce How her apsidal lancejacks is Vinnie light-heartedly, when tanked cellulosic and rectal and Hernando coupled. chaptalizing some So popular type to released, cure for the dvd copy are human! Enter your order to date on the salvatore school, so that bitter taste and leslie odom jr. Nearly nude people into a chilly smile in this at an unwarranted running theme throughout thanks for something that strapped in our traffic, breaking him vividly saturated and! The cure for her mother where top have a less materialistic society where people. A velvet for Wellness is rated R by the MPAA for disturbing violent cartoon and images sexual content including an assault graphic nudity and language. A basket for Wellness 2016 Rotten Tomatoes. This dvd release date: an effect in a cure for wellness dvd release date and more movie tickets up and all or. Financial analysis of pretty Cure for Wellness 2017 including budget domestic and international box office gross DVD and Blu-ray sales reports total earnings. That came close of the wellness dvd release date on value now in a review will. Click to explain it on so, a mountain peak with resistance by popularity, but finds no cure for family. His boss is a European wellness spa but soon realizes he's trapped. How well seemed pretty nurse, was a fully support for wellness dvd release date. Rating 1 Non-Domestic Product No Genre Horror Format DVD DVD Edition Year 2017 Certificate 1 Leading Role Dane DeHaan Release Year 2017. -

Transcript: November 5, 2020, Earnings Call of the New York Times

The New York Times Company (NYT) CEO Nov. 7, 2020 11:22 AM ET Meredith Kopit Levien on Q3 2020 Results - Earnings Call Transcript New York Times Co (NYSE:NYT) Q3 2020 Earnings Conference Call November 5, 2020 8:00 AM ET Company Participants Harlan Toplitzky - Vice President of Investor Relations Meredith Kopit Levien - President and Chief Executive Officer Roland Caputo - Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer Conference Call Participants Thomas Yeh - Morgan Stanley John Belton - Evercore ISI Alexia Quadrani - JPMorgan Doug Arthur - Huber Research Partners Vasily Karasyov - Cannonball Research Craig Huber - Huber Research Partners Kannan Venkateshwar - Barclays Operator Good morning, and welcome to The New York Times Company's Third Quarter 2020 Earnings Conference Call. All participants will be in listen-only mode. [Operator Instructions] Please note this event is being recorded. I would now like to turn the conference over to Harlan Toplitzky, Vice President, Investor Relations. Please go ahead. Harlan Toplitzky Thank you, and welcome to The New York Times Company's Third Quarter 2020 Earnings Conference Call. On the call today, we have Meredith Kopit Levien, President and Chief Executive Officer; and Roland Caputo, Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer. Before we begin, I would like to remind you that management will make forward-looking statements during the course of this call and our actual results could differ materially. Some of the risks and uncertainties that could impact our business are included in our 2019 10-K, as updated in subsequent quarterly reports on Form 10-Q. Page 1 of 19 The New York Times Company (NYT) CEO Nov. -

Regulation of Lawyers in Government Beyond the Representation Role

Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship 2019 Regulation of Lawyers in Government Beyond the Representation Role Ellen Yaroshefsky Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Ellen Yaroshefsky, Regulation of Lawyers in Government Beyond the Representation Role, 33 NOTRE DAME J. L. ETHICS & PUB. POL’Y 151 (2019) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship/1257 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REGULATION OF LAWYERS IN GOVERNMENT BEYOND THE CLIENT REPRESENTATION ROLE ELLEN YAROSHEFSKY* INTRODUCTION In February 2017, fifteen legal ethicists filed a complaint against Kellyanne Conway, Senior Counselor to the President,' alleging that a number of her pub- lic statements were intentional misrepresentations. The complaint filed in the District of Columbia, one of the two jurisdictions where Ms. Conway is admitted to practice, acknowledged that there are limited circumstances in which lawyers who do not act in a representational capacity are, and should be, subject to the anti-deceit disciplinary rules.2 The complaint stated: As Rule 8.4(c) states, "It is professional misconduct for a lawyer to [elngage in conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit, or misrepresentation." This is an admittedly broad rule, as it includes conduct outside the practice of law and, unlike 8.4(b), the conduct need not be criminal.