Afro- Caribbean Women Filmmakers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Baldwin As a Writer of Short Fiction: an Evaluation

JAMES BALDWIN AS A WRITER OF SHORT FICTION: AN EVALUATION dayton G. Holloway A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 1975 618208 ii Abstract Well known as a brilliant essayist and gifted novelist, James Baldwin has received little critical attention as short story writer. This dissertation analyzes his short fiction, concentrating on character, theme and technique, with some attention to biographical parallels. The first three chapters establish a background for the analysis and criticism sections. Chapter 1 provides a biographi cal sketch and places each story in relation to Baldwin's novels, plays and essays. Chapter 2 summarizes the author's theory of fiction and presents his image of the creative writer. Chapter 3 surveys critical opinions to determine Baldwin's reputation as an artist. The survey concludes that the author is a superior essayist, but is uneven as a creator of imaginative literature. Critics, in general, have not judged Baldwin's fiction by his own aesthetic criteria. The next three chapters provide a close thematic analysis of Baldwin's short stories. Chapter 4 discusses "The Rockpile," "The Outing," "Roy's Wound," and "The Death of the Prophet," a Bi 1 dungsroman about the tension and ambivalence between a black minister-father and his sons. In contrast, Chapter 5 treats the theme of affection between white fathers and sons and their ambivalence toward social outcasts—the white homosexual and black demonstrator—in "The Man Child" and "Going to Meet the Man." Chapter 6 explores the theme of escape from the black community and the conseauences of estrangement and identity crises in "Previous Condition," "Sonny's Blues," "Come Out the Wilderness" and "This Morning, This Evening, So Soon." The last chapter attempts to apply Baldwin's aesthetic principles to his short fiction. -

A Framework for the Static and Dynamic Analysis of Interaction Graphs

A Framework for the Static and Dynamic Analysis of Interaction Graphs DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sitaram Asur, B.E., M.Sc. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Prof. Srinivasan Parthasarathy, Adviser Prof. Gagan Agrawal Adviser Prof. P. Sadayappan Graduate Program in Computer Science and Engineering c Copyright by Sitaram Asur 2009 ABSTRACT Data originating from many different real-world domains can be represented mean- ingfully as interaction networks. Examples abound, ranging from gene expression networks to social networks, and from the World Wide Web to protein-protein inter- action networks. The study of these complex networks can result in the discovery of meaningful patterns and can potentially afford insight into the structure, properties and behavior of these networks. Hence, there is a need to design suitable algorithms to extract or infer meaningful information from these networks. However, the challenges involved are daunting. First, most of these real-world networks have specific topological constraints that make the task of extracting useful patterns using traditional data mining techniques difficult. Additionally, these networks can be noisy (containing unreliable interac- tions), which makes the process of knowledge discovery difficult. Second, these net- works are usually dynamic in nature. Identifying the portions of the network that are changing, characterizing and modeling the evolution, and inferring or predict- ing future trends are critical challenges that need to be addressed in the context of understanding the evolutionary behavior of such networks. To address these challenges, we propose a framework of algorithms designed to detect, analyze and reason about the structure, behavior and evolution of real-world interaction networks. -

PDF Download a Dry White Season Ebook Free

A DRY WHITE SEASON PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Andre Brink | 316 pages | 31 Aug 2011 | HarperCollins Publishers Inc | 9780061138638 | English | New York, NY, United States A Dry White Season PDF Book There are no race relations. Marlon Brando as McKenzie. Detroit: Gale Research, From metacritic. What does he think life is like there? There are so many passages that resonate with the barriers, pitfalls and depressing realities that never seem to change when fighting for a better world against incredible resistance and hatred: When the system is threatened they will do anything to defend it It's not cynicism, it's reality I just want to go back to the way things were Don't you think they would do the same to us if they had the chance. In this process the marriage dissolves. Thompson, Leonard. Police show up at the house with some regularity—to question the Du Toits, to search the house, and ultimately to threaten them. Cry, the Beloved Country. Susan Sarandon plays a sympathetic journalist, and Marlon Brando, in a juicy comeback cameo that evokes Orson Welles's Clarence Darrow impersonation in Compulsion , plays an antiapartheid lawyer. How can scenes of torture and of the death of children not? Afrikaner —the former term was Boer —refers to whites who descend mainly from the early Dutch but also from the early German and French settlers in the region. Trailers and Videos. It's filled with beautiful beaches, abundant wildlife, lush rainforest, lovely waterfalls and dozens of volcanos. In the book the image is rooted in a specific event. -

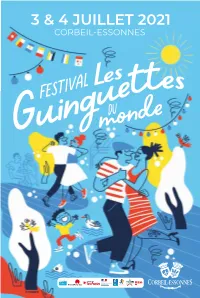

3 & 4 Juillet 2021

3 & 4 JUILLET 2021 CORBEIL-ESSONNES À L’ENTRÉE DU SITE, UNE FÊTE POPULAIRE POUR D’UNE RIVE À L’AUTRE… RE-ENCHANTER NOTRE TERRITOIRE Pourquoi des « guinguettes » ? à établir une relation de dignité Le 3 juillet Le 4 juillet Parce que Corbeil-Essonnes est une avec les personnes auxquelles nous 12h 11h30 ville de tradition populaire qui veut nous adressons. Rappelons ce que le rester. Parce que les guinguettes le mot culture signifie : « les codes, Parade le long Association des étaient des lieux de loisirs ouvriers les normes et les valeurs, les langues, des guinguettes originaires du Portugal situés en bord de rivière et que nous les arts et traditions par lesquels une avons cette chance incroyable d’être personne ou un groupe exprime SAMBATUC Bombos portugais son humanité et les significations Départ du marché, une ville traversée par la Seine et Batucada Bresilienne l’Essonne. qu’il donne à son existence et à son place du Comte Haymont développement ». Le travail culturel 15h Pourquoi « du Monde » ? vers l’entrée du site consiste d’abord à vouloir « faire Parce qu’à Corbeil-Essonnes, 93 Super Raï Band humanité ensemble ». le monde s’est donné rendez-vous, Maghreb brass band 12h & 13h30 108 nationalités s’y côtoient. Notre République se veut fraternelle. 16h15 Aquarela Nous pensons que cela est On ne peut concevoir une humanité une chance. fraternelle sans des personnes libres, Association des Batucada dignes et reconnues comme telles Alors pourquoi une fête des originaires du Portugal dans leur identité culturelle. 15h « guinguettes du monde » Bombos portugais Association Scène à Corbeil-Essonnes ? À travers cette manifestation, 18h Parce que c’est tellement bon de c’est le combat éthique de Et Sonne faire la fête. -

Beyond the Stereotypes: a Guide to Resources for Black Girls and Young Women

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 275 772 UD 025 155 AUTHOR Wilson, Geraldine, Comp.; Vassall, Merlene, Comp. TITLE Beyond the Stereotypes: A Guide to Resources for Black Girls and Young Women. INSTITUTION National Black Child Development Inst., Inc., Washington, D.C. SPONS AGENCY Women's Educational Equity Act Program (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 86 NOTE 71p.; Educational Equity for Black Girls Project: Building Achievement Motivation, Counteracting the Stereotypes. AVAILABLE FROMNational Black Child Development Inst., 1463 Rhode Island Ave., N.W., Washington, DC 20005 ($8.50). PUB TYPE Guides - General (050) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) -- Reports - Evaluative/Feasibility (142) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescents; Annotated Bibliographies; Black Attitudes; Black Culture; *Black Literature; *Blacks; *Black Youth; *Females; Films; *Preadolescents; Preschool Children; *Resource Materials ABSTRACT This resource guide lists books, records, and films that provide a realistic and wholesome depiction of what it means to be a black girl or woman. Organized according to medium and appropriate age ranges, it includes a brief annotation for each item. Suggestions for use of the guide are provided, as are the following criteria for selecting resources for black girls: (1) accurate presentation of history; (2) non-stereotypical characterization; (3) non-derogatory language and terminology; and (4) illustrations demonstrating the diversity of the black experience. Also included are distributors and -

Coopération Culturelle Caribéenne : Construire Une Coopération Autour Du Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel Anaïs Diné

Coopération culturelle caribéenne : construire une coopération autour du Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel Anaïs Diné To cite this version: Anaïs Diné. Coopération culturelle caribéenne : construire une coopération autour du Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel. Sciences de l’Homme et Société. 2017. dumas-01730691 HAL Id: dumas-01730691 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-01730691 Submitted on 13 Mar 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License Sous le sceau de l’Université Bretagne Loire Université Rennes 2 Equipe de recherche ERIMIT Master Langues, cultures étrangères et régionales Les Amériques – Parcours PESO Coopération culturelle caribéenne Construire une coopération autour du Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel Anaïs DINÉ Sous la direction de : Rodolphe ROBIN Septembre 2017 0 1 REMERCIEMENTS Je tiens à remercier toutes les personnes avec lesquelles j’ai pu échanger et qui m’ont aidé à la rédaction de ce mémoire. Je remercie tout d’abord mon directeur de recherches Rodolphe Robin pour m’avoir accompagné et soutenu depuis mes premières années à l’Université Rennes 2. Je remercie grandement l’Université Rennes 2 et l’Université de Puerto Rico (UPR) pour la formation et toutes les opportunités qu’elles m’ont offertes. -

Fall 2021 Longmont Recreation Activity Guide

Longmont RECREATION Fall 2021 arts cultura hugs reunions comunidad amigos spontaneity conexión creativity celebraciones Welcome gatherings back to HOLIDAY EVENTS . CITY INFORMATION A Message from Our Manager Welcome & Welcome Back to Longmont Recreation & Golf Services! After what feels like an eon, we are grateful to be able to offer you a full brochure of programs and activities. We missed you. From the new community event at Twin Peaks Golf Course – the Par Tee on Sept 17 – to familiar favorites like Longmont Lights and the Halloween Parade, there are times to get together and celebrate being a community. Through coordination and collaboration with local public, private, and non-profit agencies, Longmont Recreation offers diverse programming for all ages. We invite you to explore and reconnect with others this fall. Have you found yourself drawn to try something new, in terms of employment? Whether you are just starting out in your working career or exploring a different career path, Longmont Recreation & Golf Services seeks to fill over 100 part-time, full-time, benefitted and non-benefitted positions each season. Jobs exist in aquatics, athletics, business operations, fitness, building support, and custodial staff. Interviews are ongoing! Check out LongmontColorado.gov/jobs for the most current offerings. Check and see what we have to offer and find the program, event, or job that is right for you! Jeff Friesner, Recreation & Golf Manager Quick Reference Guide 3 Easy Ways to Connect with Recreation Questions? Registrations? Reservations? Register for classes beginning ONLINE [email protected] Aug 3 » Home Page: www.LongmontColorado.gov/rec , » Program Registrations: rec.ci.longmont.co.us 2021 » New in 2021: select self-service online cancellations » Park Shelter Reservations: www.LongmontColorado.gov/park-shelters IN PERSON IMPORTANT INFORMATION » Full payment is due at registration unless otherwise noted. -

M a Dry White Season

A DRY WHITE SEASON ade in 1989, A Dry White Season , things straight. He hires a lawyer, Ian this first ever release of the score, we used a searing indictment of South Africa Mackenzie (Brando), a human rights attor - only score cues and those cues are as they Munder apartheid , was a superb, riv - ney who knows the case is hopeless but were originally written and recorded. The eting film that audiences simply did not who takes it on anyway. The case is dis - film order worked beautifully in terms of dra - want to see, despite excellent reviews. Per - missed, more people die, Du Toit is threat - matic and musical flow. We’ve included two haps it was because South Africa was still ened, he is abetted in his political bonus tracks – alternate versions of two in the final throes of apartheid and the film awakening by a reporter (Susan Sarandon), cues, which bring the musical presentation was just too uncomfortable to watch. Some - has his garage bombed, and has his wife to a very satisfying conclusion. times people need distance and one sus - and daughter turn against him. Only his pects that if the film had come out even a young son knows that what Du Toit is trying Dave Grusin is one of those composers decade later it would have probably been to do is right. Eventually, gathering affidavits who can do everything. And he has – from more successful. As it is, over the years from many people, he is able to outwit the dramatic film scoring to his great work in tel - people have discovered it and been truly af - secret police and have the documents de - evision (It Takes A Thief, Maude, Good fected by its portrayal of racial turmoil in a livered to a newspaper, but in the end it Times, Baretta, The Name Of The Game, country divided and the way the film was does no real good. -

I Am Not Your Negro

Magnolia Pictures and Amazon Studios Velvet Film, Inc., Velvet Film, Artémis Productions, Close Up Films In coproduction with ARTE France, Independent Television Service (ITVS) with funding provided by Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), RTS Radio Télévision Suisse, RTBF (Télévision belge), Shelter Prod With the support of Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée, MEDIA Programme of the European Union, Sundance Institute Documentary Film Program, National Black Programming Consortium (NBPC), Cinereach, PROCIREP – Société des Producteurs, ANGOA, Taxshelter.be, ING, Tax Shelter Incentive of the Federal Government of Belgium, Cinéforom, Loterie Romande Presents I AM NOT YOUR NEGRO A film by Raoul Peck From the writings of James Baldwin Cast: Samuel L. Jackson 93 minutes Winner Best Documentary – Los Angeles Film Critics Association Winner Best Writing - IDA Creative Recognition Award Four Festival Audience Awards – Toronto, Hamptons, Philadelphia, Chicago Two IDA Documentary Awards Nominations – Including Best Feature Five Cinema Eye Honors Award Nominations – Including Outstanding Achievement in Nonfiction Feature Filmmaking and Direction Best Documentary Nomination – Film Independent Spirit Awards Best Documentary Nomination – Gotham Awards Distributor Contact: Press Contact NY/Nat’l: Press Contact LA/Nat’l: Arianne Ayers Ryan Werner Rene Ridinger George Nicholis Emilie Spiegel Shelby Kimlick Magnolia Pictures Cinetic Media MPRM Communications (212) 924-6701 phone [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 49 west 27th street 7th floor new york, ny 10001 tel 212 924 6701 fax 212 924 6742 www.magpictures.com SYNOPSIS In 1979, James Baldwin wrote a letter to his literary agent describing his next project, Remember This House. -

Implications of a Feminist Narratology: Temporality, Focalization and Voice in the Films of Julie Dash, Mona Smith and Trinh T

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 11-4-1996 Implications of a Feminist Narratology: Temporality, Focalization and Voice in the Films of Julie Dash, Mona Smith and Trinh T. Minh-ha Jennifer Alyce Machiorlatti Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Machiorlatti, Jennifer Alyce, "Implications of a Feminist Narratology: Temporality, Focalization and Voice in the Films of Julie Dash, Mona Smith and Trinh T. Minh-ha" (1996). Wayne State University Dissertations. 1674. http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations/1674 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. IMPLICATIONS OF A FEMINIST NARRATOLOGY: TEMPORALITY, FOCALIZATION AND VOICE IN THE FILMS OF JULIE DASH, MONA SMITH AND TRINH T. MINH-HA Volume I by JENNIFER ALYCE MACHIORLATTI DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 1996 MAJOR: COMMUNICATION (Radio/Television/Film) Approved by- © COPYRIGHT BY JENNIFER ALYCE MACHIORLATTI 1996 All Rights Reserved her supportive feminist perspective as well as information from the speech communication and rhetorical criticism area of inquiry. Robert Steele approached this text from a filmmaker's point of view. I also thank Matthew Seegar for guidance in the graduate program at Wayne State University and to Mark McPhail whose limited presence in my life allowed me consider the possibilities of thinking in new ways, practicing academic activism and explore endless creative endeavors. -

Society for Ethnomusicology 60Th Annual Meeting, 2015 Abstracts

Society for Ethnomusicology 60th Annual Meeting, 2015 Abstracts Walking, Parading, and Footworking Through the City: Urban collectively entrained and individually varied. Understanding their footwork Processional Music Practices and Embodied Histories as both an enactment of sedimented histories and a creative process of Marié Abe, Boston University, Chair, – Panel Abstract reconfiguring the spatial dynamics of urban streets, I suggest that a sense of enticement emerges from the oscillation between these different temporalities, In Michel de Certeau’s now-famous essay, “Walking the City,” he celebrates particularly within the entanglement of western imperialism and the bodily knowing of the urban environment as a resistant practice: a relational, development of Japanese capitalist modernity that informed the formation of kinesthetic, and ephemeral “anti-museum.” And yet, the potential for one’s chindon-ya. walking to disrupt the social order depends on the walker’s racial, ethnic, gendered, national and/or classed subjectivities. Following de Certeau’s In a State of Belief: Postsecular Modernity and Korean Church provocations, this panel investigates three distinct urban, processional music Performance in Kazakhstan traditions in which walking shapes participants’ relationships to the past, the Margarethe Adams, Stony Brook University city, and/or to each other. For chindon-ya troupes in Osaka - who perform a kind of musical advertisement - discordant walking holds a key to their "The postsecular may be less a new phase of cultural development than it is a performance of enticement, as an intersection of their vested interests in working through of the problems and contradictions in the secularization producing distinct sociality, aesthetics, and history. For the Shanghai process itself" (Dunn 2010:92). -

Contemporary World Cinema Brian Owens, Artistic Diretor – Nashville Film Festival

Contemporary World Cinema Brian Owens, Artistic Diretor – Nashville Film Festival OLLI Winter 2015 Term Tuesday, January 13 Viewing Guide – The Cinema of Europe These suggested films are some that will or may come up for discussion during the first course. If you go to Netflix, you can use hyperlinks to find further suggestions. The year listed is the year of theatrical release in the US. Some films (Ida for instance) may have had festival premieres in the year prior. VOD is “Video On Demand.” Note: It is not necessary to see any or all of the films, by any means. These simply serve as a guide for the discussion. You can also use IMDB.com (Internet Movie Database) to search for other works by these filmmakers. You can also keep this list for future viewing after the session, if that is what you prefer. Most of the films are Rated R – largely for language and brief nudity or sexual content. I’ve noted in bold the films that contain scenes that could be too extreme for some viewers. In the “Additional works” lines, those titles are noted by an asterisk. Force Majeure Director: Ruben Östlund. 2014. Sweden. 118 minutes. Rated R. A family on a ski holiday in the French Alps find themselves staring down an avalanche during lunch. In the aftermath, their dynamic has been shaken to its core. Currently playing at the Belcourt. Also Available on VOD through most services and on Amazon Instant. Ida Director: Pawel Pawlikowski. 2014. Poland. 82 minutes. Rated PG-13. A young novitiate nun in 1960s Poland, is on the verge of taking her vows when she discovers a dark family secret dating back to the years of the Nazi occupation.