Representations of Ilford in the Writings of Denise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Best Parkrun

Best Parkrun Ilford AC Park Run List 1 15.39 Blair Mcwhirter 14/10/2017 North Hagley Park Hagley Park Run SM Chelmsford Park 2 15.51 Malcolm Muir 29/06/2013 Central Park SM Run 3 16.01 Paul Grange 15/02/2020 Raphael Park Raphaels Park Run V40 4 16.05 Ahmed Abdulle 15/07/2017 Valentines Park Valentines Park Run U20 5 16.24 Ben Jones 23/04/2011 Valentines Park Valentines Park Run SM Albert Park Run 6 16.24 Tom Gardner 08/02/2020 Albert Park SM (Australia) 7 16.35 Gary Coombes 01/01/2020 Raphael Park Raphaels Park Run V40 Shepton Mallett 8 16.54 Mungo Prior 21/12/2019 Collett Park U20 Parkrun 9 17.01 Steve Philcox 10/09/2011 Valentines Park Valentines Park Run V40 10 17.04 Jak Wright 27/07/2019 Barking Park Barking Park Run U17 11 17.18 Iain Knight 30/04/2011 Valentines Park Valentines Park Run SM 12 17.26 Kevin Newell 29/11/2014 Valentines Park Valentines Park Run SM 13 17.28 Aaron Samuel 17/02/2018 Valentines Park Valentines Park Run U17 14 17.29 Sam Rahman 01/11/2014 Valentines Park Valentines Park Run SM 15 17.31 Bradley Deacon 15/02/2020 Valentines Park Valentines Park Run U17 16 17.40 Ryan Holeyman 14/03/2020 Raphael Park Raphaels Park Run U15 17 17.42 Kevin Wotton 12/05/2012 Valentines Park Valentines Park Run V40 18 17.43 Usamah Patel 14/09/2013 Valentines Park Valentines Park Run U17 19 17.46 Robin Mcnelis 12/03/2016 Raphael Park Raphaels Park Run V40 20 17.47 James Rigby 06/07/2017 Raphael Park Raphael Park Run SM 21 18.1 Haydn Newland 25/12/2019 Barking Park Barking Park Run SM 22 18.11 Joseph Grange 22/02/2020 Barking Park Barking -

London Borough of Barking and Dagenham Section 2

PARKS AND OPEN SPACES STRATEGY London Borough of Barking and Dagenham Section 2 - Technical Appendices and Evidence Base PROJECT TITLE: A1763 London Borough Of Barking and Dagenham Parks and Opens Spaces Strategy Client: The London Borough of Barking and Dagenham Version Date Version Details Prepared by Checked by Approved by Principal V1.0 Jon Sheaff, Peter Neal, Tim Gill, Jon Sheaff Jon Sheaff Sarah Williams, Aniela Zaba Peter Neal Margarida Oliveira, Julia Halasz, Visakha Sroy, Tom Jackson, Erin Gianferrara, Duncan Royle, Ian Dickie V2.0 22.06.2017 Additional information provided Jon Sheaff, Tim Gill Jon Sheaff Jon Sheaff within Section 1.3 Benchmarking and standards; Section 6.0 - Events in Barking and Dagenham and Section 7.0 - Play provision in Barking and Dagenham This document has been prepared for the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham by: Jon Sheaff and Associates Unit 5.1, Bayford Street Business Centre London E8 3SE www.jonsheaff.co.uk Study team: JSA Jon Sheaff Margarida Oliveira Julia Halasz Visakha Sroy Tom Jackson Peter Neal Tim Gill Sarah Williams Aniela Zaba Erin Gianferrara Duncan Royle Ian Dickie Acknowledgements The project team would like to thank LB Barking and Dagenham for contributing to the analysis, providing the necessary data and guidance in a timely matter. 2 LB Barking and Dagenham | Parks and Open Space Strategy | Technical Appendices and Evidence Base CONTENTS - SECTION 2 TECHNICAL APPENDICES AND EVIDENCE BASE 1.0 The Strategic Policy Context 5 7.0 Play provision in Barking and Dagenham 38 11.0 Public -

Bird Species I Have Seen World List

bird species I have seen U.K tally: 276 US tally: 394 Total world: 1,495 world list 1. Abyssinian ground hornbill 2. Abyssinian longclaw 3. Abyssinian white-eye 4. Acorn woodpecker 5. African black-headed oriole 6. African drongo 7. African fish-eagle 8. African harrier-hawk 9. African hawk-eagle 10. African mourning dove 11. African palm swift 12. African paradise flycatcher 13. African paradise monarch 14. African pied wagtail 15. African rook 16. African white-backed vulture 17. Agami heron 18. Alexandrine parakeet 19. Amazon kingfisher 20. American avocet 21. American bittern 22. American black duck 23. American cliff swallow 24. American coot 25. American crow 26. American dipper 27. American flamingo 28. American golden plover 29. American goldfinch 30. American kestrel 31. American mag 32. American oystercatcher 33. American pipit 34. American pygmy kingfisher 35. American redstart 36. American robin 37. American swallow-tailed kite 38. American tree sparrow 39. American white pelican 40. American wigeon 41. Ancient murrelet 42. Andean avocet 43. Andean condor 44. Andean flamingo 45. Andean gull 46. Andean negrito 47. Andean swift 48. Anhinga 49. Antillean crested hummingbird 50. Antillean euphonia 51. Antillean mango 52. Antillean nighthawk 53. Antillean palm-swift 54. Aplomado falcon 55. Arabian bustard 56. Arcadian flycatcher 57. Arctic redpoll 58. Arctic skua 59. Arctic tern 60. Armenian gull 61. Arrow-headed warbler 62. Ash-throated flycatcher 63. Ashy-headed goose 64. Ashy-headed laughing thrush (endemic) 65. Asian black bulbul 66. Asian openbill 67. Asian palm-swift 68. Asian paradise flycatcher 69. Asian woolly-necked stork 70. -

Shared Ownership Homes from Metropolitan

SHARED OWNERSHIP HOMES FROM METROPOLITAN 1 A collection of contemporary homes, located in the leafy Victorian suburb of Ilford, less than 30 minutes from central London. STREETS AHEAD Wanstead Park presents the unique opportunity of affordable and contemporary London living within a family focused, community orientated environment. This modern residential development offers a relaxed, suburban lifestyle and a fast, easy commute. Known as London’s ‘leafy suburb’, the green open spaces of nearby Valentines Park and Wanstead Flats compliment the traditional, close- knit neighbourly feel of this minimal, contemporary terrace style development. With a number of “outstanding” rated schools, excellent local amenities and a brief 30 minute journey to central London, this mix of three and four bedroom houses and one, two and three bedroom apartments offers the perfect foundations for family focused couples and young independent professionals. 04 05 DOWN TOWN Located in one of London’s most historic Victorian Theatre goers and film lovers will be pleased boroughs, Wanstead Park offers relaxed and leafy to find the Kenneth More Theatre and suburban living just a short walk from Ilford’s Cineworld cinema just a short walk away, dynamic and vibrant town centre. with the informative Redbridge Central Library and Museum also close by. The Exchange shopping centre and High Road are just over ten minutes walk away. Both provide an array of shops from national and international retailers. The surrounding streets offer outlets for a range of budgets and needs, while the slightly closer Cranbrook Road is home to a wide selection of independent eateries and stores covering cuisines and cultures from across the world. -

Good Parks for London 2017

''The measure of any great civilisation is in its cities, and the measure of a city's greatness is to be found in the quality of its public spaces, it's parks and squares.'' John Ruskin Sponsored by Part of Capita plc Contents Foreword..........................................................3 Part 2 Introduction.....................................................4 Signature Parks and green spaces City of London - Open space beyond the square mile...38 Overall scores...................................................8 Lee Valley Regional Park Authority............................40 Thamesmead - London’s largest housing landscape......42 Part 1 The Royal Parks......................................................43 Good Parks for London Criteria Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park..................................45 1. Public Satisfaction...........................................10 Landscape contractors 2. Awards for quality...........................................12 idverde - A whole system approach............................47 3. Collaboration with other Boroughs..................14 Glendale - Partnership in practice.............................49 4. Events.............................................................16 5. Health, fitness and well-being.........................20 Capel Manor - London’s land based college.........50 6. Supporting nature...........................................24 7. Community involvement.................................28 8. Skills development..........................................30 Valuing our parks -

Ilford London Borough of Redbridge

Historic Building and Archaeological Report Valentines Park Ilford London Borough of Redbridge Historic Building Recording and Archaeological Watching Brief o a April 2009 Client: Redbridge Borough Council Issue No: 1 OA Job No: 3560 NGR: TQ 435 880 Valentines Park, Ilford Historic Building Recording and Watching Brief Client Name: Redbridge Borough Council Document Title: Valentines Park, Ilford, London Borough of Redbridge Document Type: Historic Building Recording and Watching Brief Issue Number: 1 Grid Reference: TQ 435 880 OA Job Number: 3560 Site Code: ILVP07 (issued by Redbridge Museum but also approved by LAARC) Invoice Code: ILVPWB Receiving Museum: Redbridge Museum Service Prepared by: Nick Croxson /Sharon Cook Position: Buildings Archaeologists Date: April 2009 Checked by: Jonathan Gill Position: Senior Project Manager (Historic Buildings) Date: April 2009 Approved by: Julian Munby Signed ............................... Position: Head of Buildings Archaeology Date: April 2009 Doc file location:Server 21-db/buildings/projects ongoing/Ilford Valentines Park/report Disclaimer: This document has been prepared for the titled project or named part thereof and should not be relied upon or used for any other project without an independent check being carried out as to its suitability and prior written authority of Oxford Archaeology being obtained. Oxford Archaeology accepts no responsibility or liability for the consequences of this document being used for a purpose other than the purposes for which it was commissioned. Any person/party using or relying on the document for such other purposes agrees, and will by such use or reliance be taken to confirm their agreement to indemnify Oxford Archaeology for all loss or damage resulting therefrom. -

Wanstead Flats

WANSTEAD FLATS Individual Site Plan Date 08/01/2020 Version Number V4 Review Date Author Fiona Martin/Geoff Sinclair Land Area 187 ha Compartment Number 38 Designations Epping Forest Land (1878 Act) Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) Registered Park and Garden Archaeological Priority Area Site of Metropolitan Importance Locally Important Geological Site Green Belt Wanstead Flats Wanstead Flats INDIVIDUAL SITE PLAN SUMMARY Wanstead Flats forms the largest of the thirty-eight management compartments that comprise Epping Forest. It is an area of open acid grassland, sports pitches, heath, scrub, woodland, scattered trees and waterbodies, located at the southern end of Epping Forest; owned and managed by the City of London Corporation (COL). Wanstead Flats has a number of statutory designations and is a hugely important resource for the people of northeast London, both for its provision of sporting facilities and also for the opportunity to experience a natural environment within urban surroundings. It is one of the few breeding sites for Skylark (Alauda arvensis) in London and is a notable stop-off for migrating birds. It has a long and well-documented history, from the historical right of commoners to graze cattle and the inception of Epping Forest as a legal entity in 1878, through to World War II and modern times. Significant predicted housing growth is planned in the local area with consequent additional visitor pressure. This Individual Site Plan lists current management considerations but also presents a strategic work programme to ensure a sustainable future for the conservation and heritage interest of Wanstead Flats, along with its immense recreational value. -

London 10 Awards Artwork Revised

celebrating 20 years of excellence held at St Paul’s Cathedral London 12 May 2010 www.rics.org/awards awards sponsor Building Conservation Entries Marianne North Eagle House, The Royal College of National Theatre Gallery, London SW4 Pathologists, Studio, Royal Botanic Gardens, London SW1 London SE1 The brief was to alter and Kew, Surrey re-adapt this listed Remodelling of the Redevelopment of Major repairs to, and refurbishment of, Grade II building, which had been used as lower ground floor areas of this Grade I Grade II listed theatre aiming to retain the Victorian art gallery built specifically to house ‘Mission Rooms’ from 1895 until about 1979, listed building in Carlton House Terrace as robust practicality of the original design the artist Marianne North’s botanical paintings. to create a family home. an education centre for the College. while opening the building to new users. Project entered by: Project entered by: Project entered by: Project entered by: Donald Insall Associates Sinclair Johnson + Partners Ltd Bennetts Associates Architects Haworth Tompkins Hall Place and The Monument, Upper Lodge Water Void Practice Rooms, Gardens Restoration, London EC3 Gardens, Royal Academy of Bexley, Kent Bushy Park, Hampton, Music, NW1 This project involved Middlesex Conservation and repair refurbishment and A new building designed to of a historic building and preservation of the conservation works to the 65 metre Restoration of the Upper Lodge Water enhance the listed buildings situated around house as a major historic asset involving freestanding column of solid stone walls Gardens at Bushy Park, which had fallen it and which has revived the original town- conservation of the fabric of the house and with slit window openings and, inside, a into disrepair, including de-silting and scape objectives set out by John Nash in what removal of inappropriate features. -

Conservation Management Plans Relating to Historic Designed Landscapes, September 2016

Conservation Management Plans relating to Historic Designed Landscapes, September 2016 Site name Site location County Country Historic Author Date Title Status Commissioned by Purpose Reference England Register Grade Abberley Hall Worcestershire England II Askew Nelson 2013, May Abberley Hall Parkland Plan Final Higher Level Stewardship (Awaiting details) Abbey Gardens and Bury St Edmunds Suffolk England II St Edmundsbury 2009, Abbey Gardens St Edmundsbury BC Ongoing maintenance Available on the St Edmundsbury Borough Council Precincts Borough Council December Management Plan website: http://www.stedmundsbury.gov.uk/leisure- and-tourism/parks/abbey-gardens/ Abbey Park, Leicester Leicester Leicestershire England II Historic Land 1996 Abbey Park Landscape Leicester CC (Awaiting details) Management Management Plan Abbotsbury Dorset England I Poore, Andy 1996 Abbotsbury Heritage Inheritance tax exempt estate management plan Natural England, Management Plan [email protected] (SWS HMRC - Shared Workspace Restricted Access (scan/pdf) Abbotsford Estate, Melrose Fife Scotland On Peter McGowan 2010 Scottish Borders Council Available as pdf from Peter McGowan Associates Melrose Inventor Associates y of Gardens and Designed Scott’s Paths – Sir Walter Landscap Scott’s Abbotsford Estate, es in strategy for assess and Scotland interpretation Aberdare Park Rhondda Cynon Taff Wales (Awaiting details) 1997 Restoration Plan (Awaiting Rhondda Cynon Taff CBorough Council (Awaiting details) details) Aberdare Park Rhondda Cynon Taff -

The Collaborative City

the londoncollaborative The Collaborative City Working together to shape London’s future March 2008 THE PROJECT The London Collaborative aims to increase the capacity of London’s public sector to respond to the key strategic challenges facing the capital. These include meeting the needs of a growing, increasingly diverse and transient population; extending prosperity while safe- guarding cohesion and wellbeing, and preparing for change driven by carbon reduction. For more information visit young- foundation.org/london Abbey Wood Abchurch Lane Abchurch Yard Acton Acton Green Adams Court Addington Addiscombe Addle Hill Addle Street Adelphi Wharf Albion Place Aldborough Hatch Alder- manbury Aldermanbury Square Alderman’s Walk Alders- brook Aldersgate Street Aldersgate Street Aldgate Aldgate Aldgate High Street Alexandra Palace Alexandra Park Allhal- lows and Stairs Allhallows Lane Alperton Amen Corner Amen CornerThe Amen Collaborative Court America Square City Amerley Anchor Wharf Angel Working Angel Court together Angel to Court shape Angel London’s Passage future Angel Street Arkley Arthur Street Artillery Ground Artillery Lane Artillery AperfieldLane Artillery Apothecary Passage Street Arundel Appold Stairs StreetArundel Ardleigh Street Ashen Green- tree CourtFORE WAustinORD Friars Austin Friars Passage4 Austin Friars Square 1 AveINTRO MariaDUctio LaneN Avery Hill Axe Inn Back6 Alley Back of Golden2 Square OVerVie WBalham Ball Court Bandonhill 10 Bank Bankend Wharf Bankside3 LONDON to BarbicanDAY Barking Barkingside12 Barley Mow Passage4 -

London Green Spaces Commission

Call for evidence: London Green Spaces Commission 07 June 2019 For more information please contact: Christopher Laine MA CMLI Landscape Architect Regions Group: London and South East Region Tel: 0207 973 3473 | Mob: 07780 545 979 [email protected] Looking After Parks, Gardens and Landscapes https://historicengland.org.uk/advice/technical-advice/parks- gardens-and-landscapes/ Registered Parks and Gardens https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/what-is-designation/registered-parks- and-gardens/ 1 Historic England is the Government’s statutory adviser on all matters relating to the historic environment in England. We are a non-departmental public body sponsored by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). We champion and protect England’s historic places, providing expert advice to local planning authorities, developers, owners and communities to help ensure our historic environment is properly understood, enjoyed and cared for. London’s historic public parks, cemeteries and green spaces are important, and often the largest green infrastructure features in the capital. We enjoy an amazing inheritance, and its conservation and upkeep is critical to the liveability of the city. These parks and green spaces shape London and are part of its identity. Many of these parks are of international significance as well as valued as local green spaces. The parks and green spaces tell the story of amenity and recreation in the city from medieval churchyards and burial grounds, the creation of the Royal Parks and London’s iconic 18th century garden squares to the 19th century inner London municipal parks and garden cemeteries and late 20th century outer London country parks. -

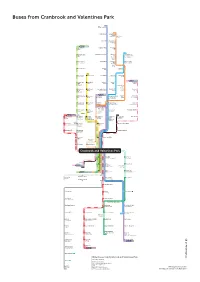

Buses from Cranbrook and Valentines Park

Buses from Cranbrook and Valentines Park EM 167 E AD R Loughton RO S O ’S N E G OR AD E RO . G T 462 S REW’S D Roding Road Limes Farm AN E. Estate . T AV S ELL R Coppereld Hail & Ride H O BET section A Valentines D Park VAUGHAN GARDENS Valley Hill Manor Road RD St. Winifred’s R E Church T ©P1ndar S S E N COWLEY ROAD HOLCOMBE H E C D 123 O R DON GARDENSENS R A EN RD Wood Green Loughton Way Grange G T AR Hill H L H GA E C AG S EL DN N G A E C FF R S R LI 150 EN C A RD D D Turnpike Lane Buckhurst Hill Manford Chigwell Row A E N G R R H Way for Hainault Forest DS IVE B AN IS Manford Country Park GHL D R I N O Primary H S S E NS N V E O School D N S D The Lake E K G N S CA R D ES ROAD E N N Lordship Lane Roding Lane Manford Manford Way E R GA D E P A The Roundway Way Manford Cross R NTI G D S O A R Hainault H N LE E G A E N L VA Health G D A IL E S T R R N H&R1 Centre V S O N A E E K O G C M T D U D Bruce Grove Chigwell Hainault A Y G R N R S E H A E Rise The Lowe N G GR Y S I I G V E R H&R2 S E A U .