Working Paper Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sholay, the Making of a Classic #Anupama Chopra

Sholay, the Making of a Classic #Anupama Chopra 2000 #Anupama Chopra #014029970X, 9780140299700 #Sholay, the Making of a Classic #Penguin Books India, 2000 #National Award Winner: 'Best Book On Film' Year 2000 Film Journalist Anupama Chopra Tells The Fascinating Story Of How A Four-Line Idea Grew To Become The Greatest Blockbuster Of Indian Cinema. Starting With The Tricky Process Of Casting, Moving On To The Actual Filming Over Two Years In A Barren, Rocky Landscape, And Finally The First Weeks After The Film'S Release When The Audience Stayed Away And The Trade Declared It A Flop, This Is A Story As Dramatic And Entertaining As Sholay Itself. With The Skill Of A Consummate Storyteller, Anupama Chopra Describes Amitabh Bachchan'S Struggle To Convince The Sippys To Choose Him, An Actor With Ten Flops Behind Him, Over The Flamboyant Shatrughan Sinha; The Last-Minute Confusion Over Dates That Led To Danny Dengzongpa'S Exit From The Fim, Handing The Role Of Gabbar Singh To Amjad Khan; And The Budding Romance Between Hema Malini And Dharmendra During The Shooting That Made The Spot Boys Some Extra Money And Almost Killed Amitabh. file download natuv.pdf UOM:39015042150550 #Dinesh Raheja, Jitendra Kothari #The Hundred Luminaries of Hindi Cinema #Motion picture actors and actresses #143 pages #About the Book : - The Hundred Luminaries of Hindi Cinema is a unique compendium if biographical profiles of the film world's most significant actors, filmmakers, music #1996 the Performing Arts #Jvd Akhtar, Nasreen Munni Kabir #Talking Films #Conversations on Hindi Cinema with Javed Akhtar #This book features the well-known screenplay writer, lyricist and poet Javed Akhtar in conversation with Nasreen Kabir on his work in Hindi cinema, his life and his poetry. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

PHARMACIST 18 K 2018.Pdf

PUNJAB PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION, LAHORE WRITTEN TEST FOR THE POSTS OF PHARMACIST (BS-17) IN THE PRIMARY & SECONDARY HEALTHCARE DEPARTMENT, 2018 NOTICE The Punjab Public Service Commission announces that the following 475 candidates for recruitment to 586 POSTS (INCLUDING 18 POSTS RESERVED FOR SPECIAL PERSONS QUOTA, 29 POSTS RESERVED FOR MINORITY QUOTA, 88 POSTS RESERVED FOR WOMAN QUOTA AND 117 POSTS RESERVED FOR SPECIAL ZONE QUOTA) OF PHARMACIST (BS-17) ON REGULAR BASIS IN THE PRIMARY & SECONDARY HEALTHCARE DEPARTMENT, have been provisionally cleared for interview as a result of written test held on 09-12-2018. 2. Call up letters for Interview will be uploaded on the website of the PPSC very soon. Candidates will also be informed through SMS and Email. 3. The candidates will be interviewed, if they are found eligible at the time of Interview as per duly notified conditions of Advertisement & Service Rules. It will be obligatory for the candidates to bring original academic certificates and related documents at the time of Interview as being intimated to them through PPSC Website, SMS and Email shortly. OPEN MERIT SR. ROLL DIARY NAME OF THE CANDIDATE FATHER'S NAME NO. NO. NO. 1 10022 25700135 ZAHEER AHMED KHAN*SPECIAL MUHAMMAD KHAN PERSON* 2 10028 25701621 AARTI DAVI*NON-MUSLIM* QEEMTI LAL 3 10030 25701708 AASMA HANIF MUHAMMAD HANIF BHATTI 4 10046 25704770 AFFAF SALMAN RIFFAT SALMAN 5 10085 25704643 ALIA RAMZAN MUHAMMAD RAMZAN 6 10090 25701936 ALINA ZEESHAN RAO RAO ZEESHAN AHMAD 7 10094 25702236 ALMAS FATIMA CHAUDRY HIDAYAT ALI 8 10106 -

Balaji Telefilms Limited 10 20 11 Company Review

annual report Balaji Telefilms Limited 10 20 11 Company Review 02 A Snapshot of Our World 04 Shifting Paradigms 06 Performance Highlights 07 Financial Highlights 08 Letter to the Shareholders 09 Managing Director’s Review Statutory Report 10 Joint Managing 14 Management Financial Statements Director’s Message Discussion & Analysis 34 Standalone Financial 11 Balaji Shows on 20 Directors’ Report Statements Television 24 Corporate Goverance 61 Consolidated 12 Board of Directors Report Financial Statements Balaji Motion Pictures Limited 86 Directors’ Report 89 Financial Statements 107 AGM Notice Forward looking statement In this Annual Report, we have disclosed forward looking information to enable investors to comprehend our prospects and take investment decisions. This report and other statements, written and verbatim, that we periodically make contain forward looking statements that set out anticipated results based on the management’s plans and assumptions. We have tried wherever possible to identify such statements by using words such as ‘anticipate’, ‘estimate’, ‘expects’, ‘projects’, ‘intends’, ‘plans’, ‘believes’, and words of similar substance in connection with any discussion of future performance. We cannot guarantee that these forward looking statements will be realised, although we believe we have been prudent in assumptions. The achievements of results are subject to risks, uncertainties, and even inaccurate assumptions. Should known or unknown risks or uncertainties materialise, or should underlying assumptions prove inaccurate, actual results could vary materially from those anticipated, estimated, or projected. Readers should keep this in mind. We undertake no obligation to publicly update any forward looking statements, whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise. Vision is all about looking ahead It is seldom static but often consistent. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

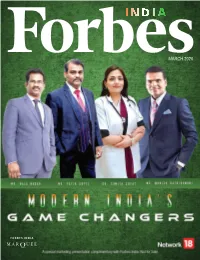

March 2020 from the Editor

MARCH 2020 FROM THE EDITOR: A visionary leader or a company that has contributed to or had a notable impact on the society is known as a game changer. India is a land of such game changers where a few modern Indians have had a major impact on India's development through their actions. These modern Indians have been behind creating a major impact on the nation's growth story. The ones, who make things happen, prove their mettle in current time and space and are highly SHILPA GUPTA skilled to face the adversities, are the true leaders. DIRECTOR, WBR Corp These Modern India's Game Changers and leaders have proactively contributed to their respective industries and society at large. While these game changers are creating new paradigms and opportunities for the growth of the nation, they often face a plethora of challenges like lack To read this issue online, visit: of funds and skilled resources, ineffective strategies, non- globalindianleadersandbrands.com acceptance, and so on. WBR Corp Locations Despite these challenges these leaders have moved beyond traditional models to find innovative solutions to UK solve the issues faced by them. Undoubtedly these Indian WBR CORP UK LIMITED 3rd Floor 207 Regent Street, maestros have touched the lives of millions of people London, Greater London, and have been forever keen on exploring beyond what United Kingdom, is possible and expected. These leaders understand and W1B 3HH address the unstated needs of the nation making them +44 - 7440 593451 the ultimate Modern India's Game Changers. They create better, faster and economical ways to do things and do INDIA them more effectively and this issue is a tribute to all the WBR CORP INDIA D142A Second Floor, contributors to the success of our great nation. -

Once Upon a Time …

- Ô RUWANTHI ABEYAKOON Happy Valentine’s Day to all those who are celebrating it out there! This week many events will take place with Valentine’s Day in heart. Amid the many celebrations you can also enjoy the art exhibitions, dramas and musical recitals that take place within this week. Read the ‘Cultural Diary’ and know where to head to break away from the busy work schedule. You can also go for the thrilling movies that are screened at well known venues. If there is an event you would like others to know, drop an email to [email protected] or call us on 011 2429652. FEBRUARY show Alex wants many viewers to free their thoughts, invent connections and discover present day myths. None FEBRUARY Once Upon is wrong as none is correct. ‘Is he dead?’ They are all a part of the meaning to be shared. Imagine find- 27 ing in an old suitcase, a collection of drawings and paintings, ‘Is He Dead?’ presented by Elizabeth Moir School will take stage at the there are angels, three wheelers, forms that are based on betel Lionel Wendt, 18, Guildford Crescent, Colombo 7 on February 18 and 19. Barefoot 18 cutters, jungle and ruins. All familiar, but no words beyond enig- Gallery a time Lionel matic titles, you are left to decipher the image for yourselves. Wendt The illustrations of unwritten tales of an unwritten history- These new paintings also reflect something of Alex’s deepen- `Once upon a time’ by Alex Stewart will take place at Barefoot ing recollections of travelling in Sri Lanka over the last 15 years Gallery, 704, Galle road, Colombo 3, until February 27. -

Satya 13 Ram Gopal Varma, 1998

THE CINEMA OF INDIA EDITED BY LALITHA GOPALAN • WALLFLOWER PRESS LO NOON. NEW YORK First published in Great Britain in 2009 by WallflowerPress 6 Market Place, London WlW 8AF Copyright © Lalitha Gopalan 2009 The moral right of Lalitha Gopalan to be identified as the editor of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transported in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owners and the above publisher of this book A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-905674-92-3 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-905674-93-0 (hardback) Printed in India by Imprint Digital the other �ide of 1 TRUTH l Hl:SE\TS IU\ffi(W.\tYEHl\"S 1 11,i:1111111,1:11'1111;1111111 11111111:U 1\ 11.IZII.IH 11.1\lli I 111 ,11 I ISll.lll. n1,11, UH.Iii 236 24 FRAMES SATYA 13 RAM GOPAL VARMA, 1998 On 3 July, 1998, a previously untold story in the form of an unusual film came like a bolt from the blue. Ram Gopal Varma'sSatya was released all across India. A low-budget filmthat boasted no major stars, Satya continues to live in the popular imagination as one of the most powerful gangster filmsever made in India. Trained as a civil engineer and formerly the owner of a video store, Varma made his entry into the filmindustry with Shiva in 1989. -

Movies of Feroz Khan

1 / 2 Movies Of Feroz Khan Feroze Khan (born July 11, 1990) is famous for being tv actor. ... Padmavati is undeniably the most awaited movie of the year and it won't be hard to call it a hit .... Feroz Khan Movies List. Thambi Arjuna (2010)Ramana, Aashima. Welcome (2007)Feroz Khan, Anil Kapoor. Ek Khiladi Ek Haseena (2005)Fardeen Khan, .... See more ideas about actors, pakistani actress, feroz khan. ... Khushbo is Pakistani film and stage Actress. c) On some minimal productions (e. Want to Become .... Tasveer Full Hindi Movie (1966) Film cast : Feroz Khan, Kalpana, Helen, Sajjan, Rajendra Nath, Nazir Hasain, Leela Mishra, Raj Mehra, Lalita Pawar, Sabeena. MUMBAI, India (Agence France-Presse) — Feroz Khan, a Bollywood ... he made “Dharmatma,” the first Hindi-language movie shot on location .... Actor Rishi Kapoor tweeted that the two actors, who worked together in three films, died of Cancer on the same date. Known for his flamboyant persona, Feroz Khan was an actor, director and producer who had a long innings in the Hindi film industry. The actor .... Feroz Khan was born at Bangalore in India to an Afghan Father, Sadiq Khan and an Iranian mother Fatima. After schooling from Bangalore he shifted to Bombay .... He would have turned 79 on September 25. However, actor, director and producer Feroz Khan – one of his kind in the Hindi film industry .... Feroz Khan All Movies List · Ek Khiladi Ek Haseena - 2005 · Ek Khiladi Ek Haseena (2005)Feroz Khan , Fardeen Khan , Koena Mitra , Gulshan Grover , Kay Kay , .... India's answer to Clint Eastwood, Feroz Khan is known as the most stylish bollywood actor. -

Proposed Position: Designer / Art Director / Film Maker

FILM C.V. Proposed Position: Designer / Art Director / Film Maker Name of the Firm: NITISH ROY DESIGN AND MEDIA Name of the Staff: Nitish Roy Profession: Designer / Art Director / Film Director Date of Birth Dec 15, 1953 Years with Firm/entity Art Direction – since 1980 Architect / Designer – since 1992 Film Direction - since 1989 Nationality: Indian Membership in Professional Societies: 1) Short Film Association of Eastern India 2) Cine & Television Art Director’s Association of India. PERSONAL PROFILE: DIRECTORIAL EXPERIENCE: 01) Directed Bengali Feature Film EK POSHLA BRISHTI 02) Directed Bengali Feature Film TOBU MONE REKHO 03) Directed T.V. serial SHAROD UTSAV for Calcutta Doordarshan. 04) Co-directed the Pilot Episode Of the children’s T.V. Serial KHEL TAMASHA 05) Produced & Directed a Children’s Puppet Film AGADOOM BAGADOOM 06) Directed Pilot Episode for T.V. Serial VERMA BANAAM VERMA 1 07) Directed T.V. Serial SAMARPAN for SKY VISION to be telecast On Zee TV 08) Directed Bengali Feature Film JAMAI NO 1 - 1998 09) Mega Television Serial MAA MANOSA (500 Episode) for ETV Bangla 10) Directed Hindi Feature Film HEART BEAT for A & A Entertainment 11) Directed Bengali Feature Film GOSAIN BAGANER BHOOT For V3G Films. 12) Directed Bengali Feature Film JOLE JONGOLE For PRINCES ART PRODUCTION. 13) Directed Bengali Feature Film NONOGA For CITROVAS FILMS. 14) Directed Bengali Feature Film TADANTO For Two Bay Ventures. 15) Directed Bengali Feature Film BUDDHUBHUTUM For Kanchan Media. RECIPIENT OF THE FOLLOWING AWARDS: Film Art direction enabled him to perfect his skills in realistic recreation. He is the recipient of the National Award 3 times for the films: ART DIRECTION: 01) KHARIJ - 1981 Directed by - Mrinal Sen National Award for Best Art Direction BFJA Award for Best Art Direction. -

The Winning Woman of Hindi Cinema

ADVANCE RESEARCH JOURNAL OF SOCIAL SCIENCE A CASE STUDY Volume 5 | Issue 2 | December, 2014 | 211-218 e ISSN–2231–6418 DOI: 10.15740/HAS/ARJSS/5.2/211-218 Visit us : www.researchjournal.co.in The winning woman of hindi cinema Kiran Chauhan* and Anjali Capila Department of Communication and Extension, Lady Irwin College, Delhi University, DELHI (INDIA) (Email: [email protected]) ARTICLE INFO : ABSTRACT Received : 27.05.2014 The depiction of women as winners has been analyzed in four sets of a total of eleven films. The Accepted : 17.11.2014 first two sets Arth (1982) and Andhi (1975) and Sahib Bibi aur Ghulam (1962), Sahib Bibi aur Gangster (2011), Sahib Bibi aur Gangster returns (2013), explore the woman in search for power within marriage. Arth shows Pooja finding herself empowered outside marriage and KEY WORDS : without any need for a husband or a lover. Whereas in Aandhi, Aarti wins political power and Winning Woman, Hindi Cinema returns to a loving marital home. In Sahib Bibi aur Ghulam choti bahu after a temporary victory of getting her husband back meets her death. In both films Sahib Bibi aur Gangster and returns, the Bibi eliminates the other woman and gangster, deactivates the husband and wins the election to gain power. she remains married and a Rani Sahiba. In the set of four Devdas makes and remakes (1927–2009) Paro is bold, shy, glamorous and ultimately liberated (Dev, 2009). Chanda moves from the looked down upon, prostitute, dancing girl to a multilingual sex worker who is empowering herself through education and treating her occupation as a stepping stone to HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE : empowerment. -

Janbaaz Mp3 Songs Download Free

Janbaaz mp3 songs download free click here to download Janbaaz () free mp3 songs download, download mp3 songs of Janbaaz ( Direct Download Links For Hindi Movie Janbaaz MP3 Songs. Janbaaz Free Mp3 Download Janbaaz Song Free Download Janbaaz Hindi Movie Mp3 Download Janbaaz Video Download Janbaaz Free Music Download. Janbaaz (): MP3 Songs. _4. Janbaaz Full HD Video Songs Download Har Kisi Ko Nahi Milta - www.doorway.ru3. Singer: Sadhana Sargam mb. Janbaaz () Hindi mp3 songs download, Sadhna Sargam, Kishore Kumar Janbaaz Songs Free Download, Janbaaz () Hindi Kbps songs, Janbaaz. Janbaaz movie Mp3 Songs Download. Tera Saath Hai Kitna Pyara kbps quality. Janbaaz movie all mp3 songs zip also available for free download. Download Complete Jaanbaaz Bollywood music album from SongsPK, www.doorway.ru Download Jaanbaaz songs, Jaanbaaz mp3 songs, Bhoomi, download. Janbaaz Songs pk Free Download MP3, Songs List: Pyar Do Pyar Lo, Jab Jab Teri Surat Dekhun, Her Kisiko Nahin Milta Pyar Duet, Allah Ho Akbar, Tera Saath. Janbaaz Mp3 Songs, Download Janbaaz, Janbaaz Songs mp3 Download, Janbaaz Bollywood, Watch Janbaaz Full Movie Online download Video Songs. 01 - Pyar Do Pyar Lo (Janbaaz ) Size: MB. Downloads: 07 - Janbaaz (Theme Song) (Janbaaz ) Size: MB. www.doorway.ru: Free Bollywood Mp3 Songs, Punjabi song, DJ Remix Songs, TV Serial Songs, Instrumental song, Singer Wise Mp3 Special Downloads () Janbaaz[Release On: ] 03 - Her Kisiko Nahin Milta Pyar (Duet).mp3. Janbaaz Songs Download- Listen Janbaaz MP3 songs online free. Play Janbaaz movie songs MP3 by Kalyanji Anandji and download Janbaaz songs on. Presenting JAB JAB TERI SURAT DEKHUN FULL VIDEO SONG from JANBAAZ movie starring Anil Kapoor.