A Local Sense of Place: Halifax's Little Dutch Church

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Boundaries of Nationality in Mid-18Th Century Nova Scotia*

GEOFFREY PLANK The Two Majors Cope: The Boundaries of Nationality in Mid-18th Century Nova Scotia* THE 1750S BEGAN OMINOUSLY IN Nova Scotia. In the spring of 1750 a company of French soldiers constructed a fort in a disputed border region on the northern side of the isthmus of Chignecto. The British built a semi-permanent camp only a few hundred yards away. The two armies faced each other nervously, close enough to smell each other's food. In 1754 a similar situation near the Ohio River led to an imperial war. But the empires were not yet ready for war in 1750, and the stand-off at Chignecto lasted five years. i In the early months of the crisis an incident occurred which illustrates many of *' the problems I want to discuss in this essay. On an autumn day in 1750, someone (the identity of this person remains in dispute) approached the British fort waving a white flag. The person wore a powdered wig and the uniform of a French officer. He carried a sword in a sheath by his side. Captain Edward Howe, the commander of the British garrison, responded to the white flag as an invitation to negotiations and went out to greet the man. Then someone, either the man with the flag or a person behind him, shot and killed Captain Howe. According to three near-contemporary accounts of these events, the man in the officer's uniform was not a Frenchman but a Micmac warrior in disguise. He put on the powdered wig and uniform in order to lure Howe out of his fort. -

ACTION STATIONS! Volume 37 - Issue 1 Winter 2018

HMCS SACKVILLE - CANADA’S NAVAL MEMORIAL ACTION STATIONS! Volume 37 - Issue 1 Winter 2018 Action Stations Winter 2018 1 Volume 37 - Issue 1 ACTION STATIONS! Winter 2018 Editor and design: Our Cover LCdr ret’d Pat Jessup, RCN Chair - Commemorations, CNMT [email protected] Editorial Committee LS ret’d Steve Rowland, RCN Cdr ret’d Len Canfield, RCN - Public Affairs LCdr ret’d Doug Thomas, RCN - Exec. Director Debbie Findlay - Financial Officer Editorial Associates Major ret’d Peter Holmes, RCAF Tanya Cowbrough Carl Anderson CPO Dean Boettger, RCN webmaster: Steve Rowland Permanently moored in the Thames close to London Bridge, HMS Belfast was commissioned into the Royal Photographers Navy in August 1939. In late 1942 she was assigned for duty in the North Atlantic where she played a key role Lt(N) ret’d Ian Urquhart, RCN in the battle of North Cape, which ended in the sinking Cdr ret’d Bill Gard, RCN of the German battle cruiser Scharnhorst. In June 1944 Doug Struthers HMS Belfast led the naval bombardment off Normandy in Cdr ret’d Heather Armstrong, RCN support of the Allied landings of D-Day. She last fired her guns in anger during the Korean War, when she earned the name “that straight-shooting ship”. HMS Belfast is Garry Weir now part of the Imperial War Museum and along with http://www.forposterityssake.ca/ HMCS Sackville, a member of the Historical Naval Ships Association. HMS Belfast turns 80 in 2018 and is open Roger Litwiller: daily to visitors. http://www.rogerlitwiller.com/ HMS Belfast photograph courtesy of the Imperial -

Cultural Assets of Nova Scotia African Nova Scotian Tourism Guide 2 Come Visit the Birthplace of Canada’S Black Community

Cultural Assets of NovA scotiA African Nova scotian tourism Guide 2 Come visit the birthplace of Canada’s Black community. Situated on the east coast of this beautiful country, Nova Scotia is home to approximately 20,000 residents of African descent. Our presence in this province traces back to the 1600s, and we were recorded as being present in the provincial capital during its founding in 1749. Come walk the lands that were settled by African Americans who came to the Maritimes—as enslaved labour for the New England Planters in the 1760s, Black Loyalists between 1782 and 1784, Jamaican Maroons who were exiled from their home lands in 1796, Black refugees of the War of 1812, and Caribbean immigrants to Cape Breton in the 1890s. The descendants of these groups are recognized as the indigenous African Nova Scotian population. We came to this land as enslaved and free persons: labourers, sailors, farmers, merchants, skilled craftspersons, weavers, coopers, basket-makers, and more. We brought with us the remnants of our cultural identities as we put down roots in our new home and over time, we forged the two together and created our own unique cultural identity. Today, some 300 years later, there are festivals and gatherings throughout the year that acknowledge and celebrate the vibrant, rich African Nova Scotian culture. We will always be here, remembering and honouring the past, living in the present, and looking towards the future. 1 table of contents Halifax Metro region 6 SoutH SHore and YarMoutH & acadian SHoreS regionS 20 BaY of fundY & annapoliS ValleY region 29 nortHuMBerland SHore region 40 eaStern SHore region 46 cape Breton iSland region 50 See page 64 for detailed map. -

EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY German Immigration to Mainland

The Flow and the Composition of German Immigration to Philadelphia, 1727-177 5 IGHTEENTH-CENTURY German immigration to mainland British America was the only large influx of free white political E aliens unfamiliar with the English language.1 The German settlers arrived relatively late in the colonial period, long after the diversity of seventeenth-century mainland settlements had coalesced into British dominance. Despite its singularity, German migration has remained a relatively unexplored topic, and the sources for such inquiry have not been adequately surveyed and analyzed. Like other pre-Revolutionary migrations, German immigration af- fected some colonies more than others. Settlement projects in New England and Nova Scotia created clusters of Germans in these places, as did the residue of early though unfortunate German settlement in New York. Many Germans went directly or indirectly to the Carolinas. While backcountry counties of Maryland and Virginia acquired sub- stantial German populations in the colonial era, most of these people had entered through Pennsylvania and then moved south.2 Clearly 1 'German' is used here synonymously with German-speaking and 'Germany' refers primar- ily to that part of southwestern Germany from which most pre-Revolutionary German-speaking immigrants came—Cologne to the Swiss Cantons south of Basel 2 The literature on German immigration to the American colonies is neither well defined nor easily accessible, rather, pertinent materials have to be culled from a large number of often obscure publications -

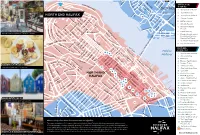

NORTH END HALIFAX T R T S T C

W In e d v t ia i m St A n S a s d e h 322 n a t e m o w W r S iv H e G i v y d 111 N l N l A s R ort e ATTRACTIONS h M R d R d a o o R n F rg d o se d a & VENUES in w d l K al D a o enc R lm H r l B DARTMOUTH rest d E e e A. The Hydrostone Market e d Ave e S st b v Bedford R Gle t er n e o B. The Halifax Forum l S A l L t s Green Rd i y e v nc v e h i t t Basin c S o e i NORTH END HALIFAX t r t S t C. The Little Dutch Church r L m k f Acadia St y G S S c nc 7 a t A N h J t u n S t o t S a n D. Creative Crossing va S t z n a l St Pauls y A l o e r lb e s NW a t P w t E. Halifax Common D s e a S y r e t rt r s R St V S S D e e o r r t J n F. Africville Museum b o a k R i t D t L rv l d e S y c a i u S s d e n s a G. -

National Historic Sites of Canada System Plan Will Provide Even Greater Opportunities for Canadians to Understand and Celebrate Our National Heritage

PROUDLY BRINGING YOU CANADA AT ITS BEST National Historic Sites of Canada S YSTEM P LAN Parks Parcs Canada Canada 2 6 5 Identification of images on the front cover photo montage: 1 1. Lower Fort Garry 4 2. Inuksuk 3. Portia White 3 4. John McCrae 5. Jeanne Mance 6. Old Town Lunenburg © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, (2000) ISBN: 0-662-29189-1 Cat: R64-234/2000E Cette publication est aussi disponible en français www.parkscanada.pch.gc.ca National Historic Sites of Canada S YSTEM P LAN Foreword Canadians take great pride in the people, places and events that shape our history and identify our country. We are inspired by the bravery of our soldiers at Normandy and moved by the words of John McCrae’s "In Flanders Fields." We are amazed at the vision of Louis-Joseph Papineau and Sir Wilfrid Laurier. We are enchanted by the paintings of Emily Carr and the writings of Lucy Maud Montgomery. We look back in awe at the wisdom of Sir John A. Macdonald and Sir George-Étienne Cartier. We are moved to tears of joy by the humour of Stephen Leacock and tears of gratitude for the courage of Tecumseh. We hold in high regard the determination of Emily Murphy and Rev. Josiah Henson to overcome obstacles which stood in the way of their dreams. We give thanks for the work of the Victorian Order of Nurses and those who organ- ized the Underground Railroad. We think of those who suffered and died at Grosse Île in the dream of reaching a new home. -

The Field of German-Canadian Studies from 2000-2017: a Bibliography

The Field of German-Canadian Studies from 2000-2017: A Bibliography English Sources Books: Antor, Heinz, Sylvia Brown, John Considine, and Klaus Stierstorfer, eds. Refractions of Germany in Canadian Literature and Culture. Berlin:Walter de Gruyter, 2003. Auger, Martin F. Prisoners of the Home Front: German POWs and “Enemy Aliens” in Southern Quebec, 1940-1946. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2005. Bassler, Gerhard. Vikings to U-boats: The German Experience in Newfoundland and Labrador. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2006. Bassler, Gerhard. Escape Hatch: Newfoundland’s Quest for German Industry and Immigration, 1950-1970. St. John’s: Flanker Press, 2017. Freund, Alexander, ed. Beyond the Nation?: Immigrants’ Local Lives in Transnational Cultures. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012. Grams, Grant. German Emigration to Canada and the Support of Its Deutschtum During the Weimar Republic: The Role of the Deutsches Ausland-Institut, Verein Für Das Deutschtum Im Ausland and German-Canadian Organisations. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2001. Hempel, Rainer L. New Voices on the Shores: Early Pennsylvania German Settlements in New Brunswick. Toronto: German-Canadian Historical Association, 2000. Hoerder, Dirk. Creating Societies: Immigrant Lives in Canada. Montreal and Kingston: McGill- Queen’s University Press, 2000. Hoerder, Dirk, and Konrad Gross, eds. Twenty-Five Years Gesellschaft für Kanada-Studien, Achievements and Perspectives. Augsburg: Wissner Verlag, 2004. Huber, Paul, and Eva Huber, eds. European Origins and Colonial Travails: The Settlement of Lunenburg. Halifax: Messenger Publications, 2003. Lorenzkowski, Barabara. Sounds of Ethnicity. Listening to German North America, 1850-1914. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2010. Maeder, Pascal. Forging a New Heimat. Expellees in Post-War West Germany and Canada. -

Anglo-French Relations and the Acadians in Canada's

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Göteborgs universitets publikationer - e-publicering och e-arkiv GOTHENBURG STUDIES IN ENGLISH 98 ______________________________________ Anglo-French Relations and the Acadians in Canada’s Maritime Literature: Issues of Othering and Transculturation BIRGITTA BROWN For C. R. Dissertation for PhD in English, University of Gothenburg 2008 © Birgitta Brown, 2008 Editors: Gunilla Florby and Arne Olofsson ISSN 0072–503x ISBN 978-91-7346-675-2 Printed by Intellecta InfoLog, Kållered 2010 Distributor: Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis, Box 222, SE-405 30 Göteborg, Sweden Abstract PhD dissertation at the University of Gothenburg, 2008 Title: Anglo-French Relations and the Acadians in Canada’s Maritime Literature: Issues of Othering and Transculturation. Author: Birgitta Brown Language: English Department: English Department, University of Gothenburg, Box 200, SE-405 30 Gothenburg Anglo-French relations have had a significant influence on the fiction created in Canada’s Maritime Provinces. The 18th century was a period of colonial wars. Contacts between the English and French in Canada were established and de- termined by the hostilities between the two colonizing nations, France and Great Britain. The hostilities passed on a sense of difference between the two nations through situations of othering. Contacts, however, always generate transcultural processes which transcend or mediate cultural difference. Othering and transculturation are closely interdependent phenomena acting in conjunc- tion. They work in processes manifesting themselves in so-called contact zones both during the colonial era and in a postcolonial context. This study investi- gates how processes of othering and transculturation are explored and dis- cussed in a number of Maritime novels, Anglophone and Acadian, published in different decades of the 20th century, in order to account for a broad perspec- tive of the interdependency of othering and transculturation. -

Recent Publications Relating to the History of the Atlantic Region

Bibliographies 155 Recent Publications Relating to the History of the Atlantic Region Editor: Eric L. Swanick, Contributors: Marion Burnett, New Brunswick. Newfoundland Wendy Duff, Nova Scotia. Frank L. Pigot, Prince Edward Island. See also: Atlantic Advocate Atlantic Insight ATLANTIC PROVINCES (This material considers two or more of the Atlantic provinces.) L'Acadie de 1604 à nos jours: exposition... /[texte par Jean-Williams Lapierre. Paris: Ed. Horarius-Chantilly, 1984] lv. (sans pagination) ill. Angus, Fred. "Requiem for the 'Atlantic'." Canadian Rail no. 367 (Aug., 1982), pp. 230- 255. ill. Allain, Greg. "Une goutte d'eau dans l'océan: regard critique sur le programme des sub ventions au développement régional du MEER dans les provinces atlantiques, 1969- 1979." Revue de l'Université de Moncton 16 (avril/déc, 1983), pp. 77-109. Atlantic Oral History Association Conference (1981: Glace Bay, N.S.). Proceedings of the Atlantic Oral History Association Conference, Glace Bay, 1981 /edited by Elizabeth Beaton-Planetta. Sydney, N.S.: University College of Cape Breton Press. cl984, 107 p. Bates, John Seaman. By the way, 1888-1983. Hantsport, N.S.: Lancelot Press, 1983. 132 p. Bickerton, James and Alain G. Gagnon. "Regional policy in historical perspective: the federal role in regional economic development." American Review of Canadian Studies 14 (Spring, 1984), pp. 72-92. Brown, Matthew Paul. The political economy and public administration of rural lands in Canada: New Brunswick and Nova Scotia perspectives. Ph.D. dissertation, Univer sity of Toronto, 1982. 5 microfiches. (Canadian theses on microfiche; no. 55763) Burley, David V. "Cultural complexity and evolution in the development of coastal adap tations among the Micmac and coastal Salish." In The evolution of Maritime cultures on the northeast and northwest coasts of America /edited by Ronald J. -

Huguenot Silversmiths in London, 1685-1715

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2001 Huguenot Silversmiths in London, 1685-1715 Brooke Gallagher Reusch College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Reusch, Brooke Gallagher, "Huguenot Silversmiths in London, 1685-1715" (2001). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626324. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-w1pb-br78 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HUGUENOT SILVERSMITHS IN LONDON 1685-1715 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of the Arts by Brooke Gallagher Reusch 2001 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts * Author Approved, May 2001 Dale Hoak LuAnn Homza James Whittenburg. j i i This thesis is dedicated to my husband, Jason Reusch, and my parents, P. Robert and Alzada Gallagher. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS V LIST OF PLATES vi ABSTRACT ix CHAPTER I: A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE HUGUENOTS 2 CHAPTER II: ASSIMILATION 29 CHAPTER III: HUGUENOT SILVERSMITHS IN LONDON 38 CHAPTER IV: CONCLUSION 68 APPENDIX 73 BIBLIOGRAPHY 107 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The writer wishes to express her gratitude to Professor Dale Hoak for his countless suggestions and valuable criticism that he gave throughout this process. -

The History of the Canadian Governmental Representation in Germany 1

J ASPER M. T RAUTSCH The History of the Canadian Governmental Representation in Germany 1 ____________________ Zusammenfassung Dieser Artikel rekonstruiert die Geschichte der staatlichen Präsenz Kanadas in Deutschland. Über viele Jahre war die Geschichte der deutsch-kanadischen Beziehun- gen durch außergewöhnliche Umstände gekennzeichnet. Die verhältnismäßig junge Geschichte beider Staaten, Kanadas strukturelle Abhängigkeit von seinem einstigen Mutterland bei außenpolitischen Entscheidungen bis weit ins 20. Jahrhundert hinein, die entgegengesetzten Interessen hinsichtlich Auswanderung und Handelspolitik und nicht zuletzt die beiden Weltkriege haben die Entwicklung „normaler“ Beziehungen zwischen beiden Nationen verzögert. Im 19. und frühen 20. Jahrhundert gab es nur informelle deutsch-kanadische Beziehungen, die durch kanadische Einwanderungsbü- ros und Handelsbüros institutionalisiert waren. Erst nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg eröff- nete Kanada auch eine diplomatische Vertretung in Deutschland, die sukzessive vergrö- ßert wurde. Seit Beginn des Kalten Krieges gehörte zur staatlichen Präsenz Kanadas auch die Stationierung kanadischer Truppen in Westdeutschland als Teil des westlichen Verteidigungsbündnisses. Der Artikel zeichnet somit nach, wie sich Kanadas Präsenz in Deutschland von den Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts beginnenden teilweise heimlichen Aktivitäten der Einwanderungsagenturen und den im frühen 20. Jahrhundert entstan- denen Handelsbüros bis hin zur Gründung regulärer diplomatischer Vertretungen und der Stationierung tausender kanadischer -

Acadian Exiles: a Chronicle of the Land of Evangeline Arthur G

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Maine History Documents Special Collections 1922 Acadian Exiles: a Chronicle of the Land of Evangeline Arthur G. Doughty Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory Part of the History Commons Repository Citation Doughty, Arthur G., "Acadian Exiles: a Chronicle of the Land of Evangeline" (1922). Maine History Documents. 27. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory/27 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History Documents by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHRONICLES OF CANADA Edited by George M. Wrong and H. H. Langton In thirty-two volumes 9 THE ACADIAN EXILE BY ARTHUR G. DOUGHTY Part III The English Invasion IN THE PARISHCHURCH AT GRAND PRE, 1755 From a colour drawing by C.W. Jefferys THE ACADIAN EXILES A Chronicle of the Land of Evangeline BY ARTHUR G. DOUGHTY TORONTO GLASGOW, BROOK & COMPANY 1922 Copyright in all Countries subscribing to the Berne Conrention TO LADY BORDEN WHOSE RECOLLECTIONS OF THE LAND OF EVANGELINE WILL ALWAYS BE VERY DEAR CONTENTS Paee I. THE FOUNDERS OF ACADIA . I II. THE BRITISH IN ACADIA . 17 III. THE OATH OF ALLEGIANCE . 28 IV. IN TIMES OF WAR . 47 V. CORNWALLIS AND THE ACADIANS 59 VI. THE 'ANCIENT BOUNDARIES' 71 VII. A LULL IN THE CONFLICT . 83 VIII. THE LAWRENCE REGIME 88 IX. THE EXPULSION . 114 X. THE EXILES . 138 BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE . 162 INDEX 173 ILLUSTRATIONS IN THE PARISH CHURCH AT GRAND PRE, 1758 .