1. Introduction. It Is a Fact That the Consumption of Illegal Drugs Is A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nt Venues Association Unites to Save Our Stages by DAN ENGLAND

7.25” x 9.875” 2 album reviews BandWagon VIVIAN PG. 4 Magazine A.M. PleAsure ASsassins PG. 5 andy sydow PG. 6 BandWagMag BandWagMag 802 9th St. Greeley, CO 80631 BANDWAGMAG.COM THE COLORADO PUBLISHER SOUND’S my5 PG. 11 ELY CORLISS EDITOR KEVIN JOHNSTON ART DIRECTOR CARTER KERNS CONTRIBUTORS DAN ENGLAND VALERIE VAMPOLA the fate of festival future music education goes NATE WILDE PG. 12 LAURA GIAGOS onlinePG. 10 PG. 16 ATTN: BANDS AND MUSICIANS Submit your album for review: BandWagon MAgazine 802 9th St. Greeley, CO 80631 or [email protected] CONTACT US Advertising Information: [email protected] Editorial Info/Requests: [email protected] Any other inquiries: [email protected] BandWagon Magazine PG. 20 © 2020 The Crew Presents Inc. NATIONAL INDEPENDENT VENUE ASSOSIATION 3 VIVIAN The Warped Glimmer Laura Giagos and puts the seat back for the BandWagon Magazine listener. It’s a warm envelope to rest in but exciting enough not to put you to sleep. VIVIAN’s Tim Massa and Alana Rolfe came out of big changes leading up to quarantine: Massa went through a divorce and their other band Stella Luce ended after ten years. Suddenly, they began cranking out songs. “There’s a sense of urgency but an overwhelming sense of loss,” says Rolfe, “It’s so confusing it makes your head want to split in half.” Covid-19 has changed much “In the last two years I really of what we love about music – got into home recording and some possibly forever – but the beat production,” Massa says. “I indomitable spirit of musicians was working on some stuff as continues to persevere. -

Elvis Presley Music

Vogue Madonna Take on Me a-ha Africa Toto Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This) Eurythmics You Make My Dreams Daryl Hall and John Oates Taited Love Soft Cell Don't You (Forget About Me) Simple Minds Heaven Is a Place on Earth Belinda Carlisle I'm Still Standing Elton John Wake Me Up Before You Go-GoWham! Blue Monday New Order Superstition Stevie Wonder Move On Up Curtis Mayfield For Once In My Life Stevie Wonder Red Red Wine UB40 Send Me On My Way Rusted Root Hungry Eyes Eric Carmen Good Vibrations The Beach Boys MMMBop Hanson Boom, Boom, Boom!! Vengaboys Relight My Fire Take That, LuLu Picture Of You Boyzone Pray Take That Shoop Salt-N-Pepa Doo Wop (That Thing) Ms Lauryn Hill One Week Barenaked Ladies In the Summertime Shaggy, Payvon Bills, Bills, Bills Destiny's Child Miami Will Smith Gonna Make You Sweat (Everbody Dance Now) C & C Music Factory Return of the Mack Mark Morrison Proud Heather Small Ironic Alanis Morissette Don't You Want Me The Human League Just Cant Get Enough Depeche Mode The Safety Dance Men Without Hats Eye of the Tiger Survivor Like a Prayer Madonna Rocket Man Elton John My Generation The Who A Little Less Conversation Elvis Presley ABC The Jackson 5 Lessons In Love Level 42 In the Air Tonight Phil Collins September Earth, Wind & Fire In Your Eyes Kylie Minogue I Want You Back The Jackson 5 Jump (For My Love) The Pointer Sisters Rock the Boat Hues Corportation Jolene Dolly Parton Never Too Much Luther Vandross Kiss Prince Karma Chameleon Culture Club Blame It On the Boogie The Jacksons Everywhere Fleetwood Mac Beat It -

L Master of L»Well Lodge, Tor for the Lowell State Bank, F

7 y LEDGER Odds and Ends Q Here and There ENTRIES Lmos and ALTO SOLO Pithy Points Picked Up and BdkC a af Variaaa Patly Pot By Our Peripa- Tapica af Lacal aad LOWELL. MICHIGAN. THURSDAY, DECEMBER 28.1933 NO. 32 tetic Pencil Pusher Gaaeral Utcrcat FORTY-FIRST YEAR Happy New Year! Happy Year! Wm. E. Aldrich, 69, By Albert T. Rpid To dale more than 3.0(H) appli- WB CANT STOP NOW COMES TO GRIEFBom Near Here, Dies RING IN THE NEW cations for Old Age pensions are unmistakable William E. Aldrich, 09. prom- have been made in Kenl county. everywhere of im inent farmer of southwest Barry svement ID econonnc county, died unexpectedly at his We can see where the Slate TRYING HOLDUP home near Delton Wednesday Supreme Court has cited Ihe offi- More men are at night, Dec. 20. millions of them. Farm- cials governing body of the sec- noting some improve- The son of William B. Aldrich. ond city of Ihe slate for con- prices. Retail business IN DRUGSTORE Civil war veteran residng many tempi. Thp (K-ople had already- years in Lowell and vicinity, ho done thai. Many of the big in- was born in Vergennes township. report more orders on THOMAS WATERS ALLEGED Kent county, lie was married in for some years past The Pere Marquette Hailwav TO HAVE ATTEMPTED BOB- June 19. 1883, to Etta Jane Whit- Co., asked permission of the in- Prices Are rising. The bank re- ney. Grattan township, who died terstate commerce commission ports for October showed that BERY IN DETROIT—FORM- Mbrch 3. -

Love Ain't Got No Color?

Sayaka Osanami Törngren LOVE AIN'T GOT NO COLOR? – Attitude toward interracial marriage in Sweden Föreliggande doktorsavhandling har producerats inom ramen för forskning och forskarutbildning vid REMESO, Institutionen för Samhälls- och Välfärdsstudier, Linköpings universitet. Samtidigt är den en produkt av forskningen vid IMER/MIM, Malmö högskola och det nära samarbetet mellan REMESO och IMER/MIM. Den publiceras i Linköping Studies in Arts and Science. Vid filosofiska fakulteten vid Linköpings universitet bedrivs forskning och ges forskarutbildning med utgångspunkt från breda problemområden. Forskningen är organiserad i mångvetenskapliga forskningsmiljöer och forskarutbildningen huvudsakligen i forskarskolor. Denna doktorsavhand- ling kommer från REMESO vid Institutionen för Samhälls- och Välfärdsstudier, Linköping Studies in Arts and Science No. 533, 2011. Vid IMER, Internationell Migration och Etniska Relationer, vid Malmö högskola bedrivs flervetenskaplig forskning utifrån ett antal breda huvudtema inom äm- nesområdet. IMER ger tillsammans med MIM, Malmö Institute for Studies of Migration, Diversity and Welfare, ut avhandlingsserien Malmö Studies in International Migration and Ethnic Relations. Denna avhandling är No 10 i avhandlingsserien. Distribueras av: REMESO, Institutionen för Samhälls- och Välfärsstudier, ISV Linköpings universitet, Norrköping SE-60174 Norrköping Sweden Internationell Migration och Etniska Relationer, IMER och Malmö Studies of Migration, Diversity and Welfare, MIM Malmö Högskola SE-205 06 Malmö, Sweden ISSN -

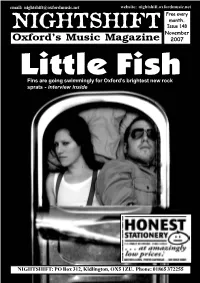

Issue 148.Pmd

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 148 November Oxford’s Music Magazine 2007 Little Fish Fins are going swimmingly for Oxford’s brightest new rock sprats - interview inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] AS HAS BEEN WIDELY Oxford, with sold-out shows by the REPORTED, RADIOHEAD likes of Witches, Half Rabbits and a released their new album, `In special Selectasound show at the Rainbows’ as a download-only Bullingdon featuring Jaberwok and album last month with fans able to Mr Shaodow. The Castle show, pay what they wanted for the entitled ‘The Small World Party’, abum. With virtually no advance organised by local Oxjam co- press or interviews to promote the ordinator Kevin Jenkins, starts at album, `In Rainbows’ was reported midday with a set from Sol Samba to have sold over 1,500,000 copies as well as buskers and street CSS return to Oxford on Tuesday 11th December with a show at the in its first week. performers. In the afternoon there is Oxford Academy, as part of a short UK tour. The Brazilian elctro-pop Nightshift readers might remember a fashion show and auction featuring stars are joined by the wonderful Metronomy (recent support to Foals) that in March this year local act clothes from Oxfam shops, with the and Joe Lean and the Jing Jang Jong. Tickets are on sale now, priced The Sad Song Co. - the prog-rock main concert at 7pm featuring sets £15, from 0844 477 2000 or online from wegottickets.com solo project of Dive Dive drummer from Cyberscribes, Mr Shaodow, Nigel Powell - offered a similar deal Brickwork Lizards and more. -

Requiem Mass the WHOLE STORY COMPILED from JUDGE’S POSTS on HIS PROJECT FACEBOOK PAGE ‘A LOST PROG-ROCK MASTERPIECE’

Judge Smith - requiem mass THE WHOLE STORY COMPILED FROM JUDGE’S POSTS ON HIS PROJECT FACEBOOK PAGE ‘A LOST PROG-ROCK MASTERPIECE’ 24 September 2015 · So folks, I’ve decided that it’s time for me to put-up or shut-up about this blessed Requiem. I wrote it in 1973 -75, and it is perhaps my best music, but it is so demanding of resources that I’ve never before been able to contemplate recording it. Not that it’s particularly long; it’s not another ‘Curly’s Airships’, which weighed-in at 2 hours 20 minutes. It’s just a half- hour piece, but it does require the full, real-world participation of a sizable choir; a two- guitars, bass and drums rock band, a solo singer, orchestral percussion, and an eight-piece brass-section. And they all need to be good. Altogether that’s a big undertaking, but I’ve recently realised that I really don’t want to shuffle off this mortal whatsaname without having heard the thing. I would feel a failure. So I’m going to do it now while I still can. This is the story, it’s quite interesting if you are into this sort of thing... In the late 60s I co-founded a band called Van der Graaf Generator. We were one of the first wave of British bands (or ‘groups’, as they were still called) which were founded with the express purpose of developing some sort of music that went beyond the expectations of the Pop charts. Other established, and somewhat older, bands, who were already global ‘pop stars’ with strings of massive three-minute hits behind them, were also starting to move in this experimental or ‘progressive’ direction, and their millions of fans and their attendant, wealthy record companies, always eager to invest in the next big thing, meant that for a brief period of a few years, there was actually a possibility of making a career out of playing peculiar music. -

MUG Songsheets Book 7: Contents

MUG Songsheets Book 7: Contents 1. Walk of Life Dire Straits 2. The Locomotion Little Eva 3. Rockin’ in the Free World Neil Young 4. The Letter The Box Tops 5. Lazy Sunday Small Faces 6. The Young Ones Cliff Richard & The Shadows 7. Early Morning Rain Gordon Lightfoot 8. The Wanderer Dion 9. Hang On Sloopy The McCoys 10. Black Velvet Band The Dubliners, etc. 11. Wild Rover The Dubliners, etc. 12. Rock and Roll Music Chuck Berry, The Beatles 13. A Picture of You Joe Brown 14. Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds The Beatles 15. Wonderful World Sam Cooke 16. Paint It Black The Rolling Stones 17. Shotgun George Ezra 18. Ruby Kaiser Chiefs 19. Alright Supergrass 20. Here Comes My Baby Cat Stevens, The Tremeloes 21. You Were Made For Me Freddie and the Dreamers 22. Golden Brown The Stranglers 23. Sundown Gordon Lightfoot 24. Dakota Stereophonics 25. Bad Moon Rising Creedence Clearwater Revival 26. Dancing In the Dark Bruce Springsteen 27. Honky Tonk Women The Rolling Stones 28. Sweet Dreams are Made of This The Eurythmics 29. I Haven’t Told Her, She Hasn’t Told Me Art Fowler 30. Echo Beach Martha and the Muffins 31. Take It Easy The Eagles 32. Poetry In Motion Johnny Tillotson 33. Manic Monday The Bangles 34. Singin’ In The Rain Gene Kelly 35. The Last Time The Rolling Stones 36. The Gambler Kenny Rogers 37. Gimme! Gimme! Gimme! ABBA 38. With a Little Help From My Friends The Beatles 39. All You Need is Love The Beatles MUG Songsheets Book 7: Alphabetical Contents 13. -

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title American Tan: Modernism, Eugenics, and the Transformation of Whiteness Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/48g022bn Author Daigle, Patricia Lee Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara American Tan: Modernism, Eugenics, and the Transformation of Whiteness A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the History of Art and Architecture by Patricia Lee Daigle Committee in charge: Professor E. Bruce Robertson, Chair Professor Laurie Monahan Professor Jeanette Favrot Peterson September 2015 The dissertation of Patricia Lee Daigle is approved. __________________________________________ Laurie Monahan __________________________________________ Jeanette Favrot Peterson __________________________________________ E. Bruce Robertson, Chair August 2015 American Tan: Modernism, Eugenics, and the Transformation of Whiteness Copyright © 2015 by Patricia Lee Daigle iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In many ways, this dissertation is not only a reflection of my research interests, but by extension, the people and experiences that have influenced me along the way. It seems fitting that I would develop a dissertation topic on suntanning in sunny Santa Barbara, where students literally live at the beach. While at the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB), I have had the fortunate experience of learning from and working with several remarkable individuals. First and foremost, my advisor Bruce Robertson has been a model for successfully pursuing both academic and curatorial endeavors, and his encyclopedic knowledge has always steered me in the right direction. Laurie Monahan, whose thoughtful persistence attracted me to UCSB and whose passion for art history and teaching students has been inspiring. -

Nr Kat Artysta Tytuł Title Supplement Nośnik Liczba Nośników Data

nr kat artysta tytuł title nośnik liczba data supplement nośników premiery 9985841 '77 Nothing's Gonna Stop Us black LP+CD LP / Longplay 2 2015-10-30 9985848 '77 Nothing's Gonna Stop Us Ltd. Edition CD / Longplay 1 2015-10-30 88697636262 *NSYNC The Collection CD / Longplay 1 2010-02-01 88875025882 *NSYNC The Essential *NSYNC Essential Rebrand CD / Longplay 2 2014-11-11 88875143462 12 Cellisten der Hora Cero CD / Longplay 1 2016-06-10 88697919802 2CELLOSBerliner Phil 2CELLOS Three Language CD / Longplay 1 2011-07-04 88843087812 2CELLOS Celloverse Booklet Version CD / Longplay 1 2015-01-27 88875052342 2CELLOS Celloverse Deluxe Version CD / Longplay 2 2015-01-27 88725409442 2CELLOS In2ition CD / Longplay 1 2013-01-08 88883745419 2CELLOS Live at Arena Zagreb DVD-V / Video 1 2013-11-05 88985349122 2CELLOS Score CD / Longplay 1 2017-03-17 0506582 65daysofstatic Wild Light CD / Longplay 1 2013-09-13 0506588 65daysofstatic Wild Light Ltd. Edition CD / Longplay 1 2013-09-13 88985330932 9ELECTRIC The Damaged Ones CD Digipak CD / Longplay 1 2016-07-15 82876535732 A Flock Of Seagulls The Best Of CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88883770552 A Great Big World Is There Anybody Out There? CD / Longplay 1 2014-01-28 88875138782 A Great Big World When the Morning Comes CD / Longplay 1 2015-11-13 82876535502 A Tribe Called Quest Midnight Marauders CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 82876535512 A Tribe Called Quest People's Instinctive Travels And CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88875157852 A Tribe Called Quest People'sThe Paths Instinctive Of Rhythm Travels and the CD / Longplay 1 2015-11-20 82876535492 A Tribe Called Quest ThePaths Low of RhythmEnd Theory (25th Anniversary CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88985377872 A Tribe Called Quest We got it from Here.. -

The Stranglers Forgotten Heroes Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Stranglers Forgotten Heroes mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Forgotten Heroes Style: New Wave, Punk MP3 version RAR size: 1385 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1207 mb WMA version RAR size: 1561 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 710 Other Formats: AUD VOX AIFF AAC ASF APE RA Tracklist 1 Threatened 3:13 2 Straighten Out 2:55 3 Burning Up Time 2:44 4 London Lady 2:18 5 Down In The Sewer 6:49 6 5 Minutes 3:42 7 Toiler On The Sea 5:48 8 (Get A) Grip (On Yourself) 3:43 9 Dagenham Dave 3:18 10 Bring On The Nubiles 2:50 11 Dead Ringer 2:36 12 Hanging Around 4:17 13 Nice 'n' Sleazy 3:38 14 No More Heroes 3:39 15 Tank 2:57 Credits Drums – Jet Black Keyboards – Dave Greenfield Vocals, Bass – JJ Burnel* Vocals, Guitar – Hugh Cornwell Written-By – The Stranglers Notes "All songs written and performed by The Stranglers at Agora, Cleveland, USA on 3rd April 1978. These historic sound recordings may contain some surface noise or distortion due to the age of the master recordings under use." Track 2 and 3 printed in reversed running order on sleeve Track 6 mistitled as "Down In The Sewer (Reprise)" on sleeve Track 13 mistitled as "Nice 'N Sleazy" on sleeve. Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout: IMPRESS PYCD064 03 6 Matrix / Runout: MADE IN THE UK BY UNIVERSAL Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Forgotten Heroes (CD, PYCD 064 The Stranglers Triangle Records PYCD 064 Italy 1991 Unofficial) Related Music albums to Forgotten Heroes by The Stranglers Stranglers, The - No More Heroes The Stranglers - Greatest Hits On CD&DVD The Stranglers - The Meninblack In Colour 1983 - 1990 The Stranglers - No More Heroes The Stranglers - Black And White (Live) The Stranglers - The Radio 1 Sessions - The Evening Show The Stranglers - Nice 'n' Sleazy The Stranglers - Death And Night And Blood. -

John Ellis Full Biog 2018

JOHN ELLIS BULLET BIOG 2018 Formed the legendary BAZOOKA JOE Band members included Adam Ant. First Sex Pistols gig was as support to Bazooka Joe. A very influential band despite making no records. Formed THE VIBRATORS. Released 2 albums for Epic. Also played with Chris Spedding on TV and a couple of shows. REM covered a Vibrators single. Extensive touring and TV/Radio appearances including John Peel sessions. Released 2 solo singles. Played guitar in Jean-Jacques Burnel’s Euroband for UK tour. Formed RAPID EYE MOVEMENT featuring HOT GOSSIP dancers and electronics. Supported Jean-Jacques Burnel’s Euroband on UK tour. Joined Peter Gabriel Band for “China” tour and played on Gabriel’s 4th solo album. Stood in for Hugh Cornwell for 2 shows by THE STRANGLERS at the Rainbow Theatre. Album from gig released. Worked with German duo ISLO MOB on album and single. Started working with Peter Hammill eventually doing many tours and recording on 7 albums. Rejoined THE VIBRATORS for more recording and touring. Founder and press officer for the famous M11 Link Road campaign. Recorded 2 albums under the name of PURPLE HELMETS with Jean-Jacques Burnel and Dave Greenfield of THE STRANGLERS. Played additional guitar on THE STRANGLERS ‘10’ tour. Joined THE STRANGLERS as full time member. Extensive touring and recording over 10 years. Many albums released including live recording of Albert Hall show. Played many festivals across the world. Many TV and Radio appearances. Started recording series of electronic instrumental albums as soundtracks for Art exhibitions. 5 CDs released by Voiceprint. Also released WABI SABI 21©, the first of a trilogy of albums inspired by Japanese culture. -

AYITI CHERIE, MY DARLING HAITI by Nimi Finnigan, B.S, M.F.A A

AYITI CHERIE, MY DARLING HAITI by Nimi Finnigan, B.S, M.F.A A Dissertation In ENGLISH Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Dennis Covington Chair of Committee Michael Borshuk Jackie Kolosov-Wenthe Peggy Gordon Miller Dean of the Graduate School May 2012 Copyright 2012, Nimi Finnigan Texas Tech University, Nimi Finnigan, May 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe a debt of gratitude to a number of people without whom Ayiti Cherie, My Darling Haiti would never have been completed: Dennis Covington, who not only served as my supervisor but also introduced me to literary nonfiction, as well as Jackie Kolosov and Michael Borshuk for generously giving of their time and advice and for putting up with me. And as always, I still have not found the right words to thank and honor Mousson and Sean, who edited the manuscript for the facts, but more importantly who remind me to just be Nimi Finnigan through everything that I do because that’s enough. ii Texas Tech University, Nimi Finnigan, May 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................... II ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................. IV 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1 Creative Nonfiction Overview: It’s All about the Latticework ................................