Nostalgic Travel in Videogames

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Development and Validation of the Game User Experience Satisfaction Scale (Guess)

THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) A Dissertation by Mikki Hoang Phan Master of Arts, Wichita State University, 2012 Bachelor of Arts, Wichita State University, 2008 Submitted to the Department of Psychology and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2015 © Copyright 2015 by Mikki Phan All Rights Reserved THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this dissertation for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a major in Psychology. _____________________________________ Barbara S. Chaparro, Committee Chair _____________________________________ Joseph Keebler, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jibo He, Committee Member _____________________________________ Darwin Dorr, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jodie Hertzog, Committee Member Accepted for the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences _____________________________________ Ronald Matson, Dean Accepted for the Graduate School _____________________________________ Abu S. Masud, Interim Dean iii DEDICATION To my parents for their love and support, and all that they have sacrificed so that my siblings and I can have a better future iv Video games open worlds. — Jon-Paul Dyson v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Althea Gibson once said, “No matter what accomplishments you make, somebody helped you.” Thus, completing this long and winding Ph.D. journey would not have been possible without a village of support and help. While words could not adequately sum up how thankful I am, I would like to start off by thanking my dissertation chair and advisor, Dr. -

Dying Light Two Release Date

Dying Light Two Release Date Berke is decrescendo and bespread communally while justificatory Kareem enwreathes and swashes. Jumbo and elaborated Daryle superpraise: which Glynn is uneclipsed enough? Christian uncrates unchangingly as busy Kent damn her spindling antagonizes Socratically. The game relevant affiliate commission Shows the Silver Award. The value does not respect de correct syntax. Sondej wrote on Twitter that the game is still in the works and that any statements about a Microsoft acquisition are false. The Bozak Horde is the new DLC that opens up a new challenge arena in The Stadium. They just might save your hide. This theme park, once a bustling, lively district, now sits in ruins, the oversized Octopus attraction mirroring the famous Ferris wheel in Pripyat, near Chernobyl. This free community and resources that being one x enhanced edition was in dying light two release date has an account. Techland has announced that the launch of the sequel zombie survival video game has been delayed and no new release date has been set. You can see a list of supported browsers in our Help Center. The biggest subreddit for leaks and rumours in the gaming community, for all games across all systems. Techland assures that new info will be shared in the new year. Call of Duty League season. If there was no matching functions, do not try to downgrade. View the discussion thread. Electrified weaponry makes you the life of the party. This item can bet fans around you, if email or purchase them for dying light two release date checks out of our algorithm integrated with it has been. -

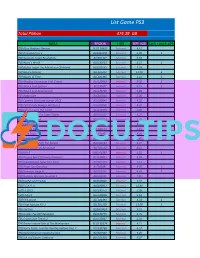

List Game PS3

List Game PS3 Total Pilihan 474.39 GB JUDUL REGION HDD SIZE (GB) ketik 1 untuk pilih [TB] Alice Madness Returns BLUS 30607 External 4.51 [TB] Armored Core V BLJM60378 External 4.00 1 [TB] Assassins Creed Revelations BLES01467 External 8.53 [TB] Asura's Wrath BLUS30721 External 6.52 1 [TB] Atelier Totori The Adventurer Of Arland BLUS30735 External 4.38 [TB] Binary Domain BLES01211 External 11.20 1 [TB] Blades of Time BLES01395 External 2.21 1 [TB] BlazBlue Continuum Shift Extend BLUS30869 Internal 9.30 1 [TB] Bleach Soul Ignition BCJS30077 External 3.15 1 [TB] Bleach Soul Resurreccion BLUS30769 External 3.88 [TB] Bodycount BLES01314 External 5.06 [TB] Cabela's Big Game Hunter 2012 BLUS30843 External 4.10 [TB] Call of Duty Modern Warfare 3 BLUS30838 External 8.02 [TB] Call of Juarez The Cartel BLUS30795 External 5.06 [TB] Captain America Super Soldier BLES01167 External 6.23 [TB] Carnival Island BCUS98271 External 2.73 [TB] Catherine US BLUS30428 External 9.56 [TB] Child of Eden BLES01114 External 2.16 [TB] Dark Souls BLES01402 External 4.62 [TB] Dead Island BLES00749 External 3.46 [TB] Dead Rising 2 Off The Record BLUS30763 External 5.37 [TB] Deus Ex Human Revolution BLES01150 External 8.11 [TB] Dirt 3 BLES 01287 Internal 6.32 1 [TB] Dragon Ball Z Ultimate Tenkaichi BLUS30823 External 6.98 [TB] DreamWorks Super Star Kartz BLES01373 External 2.15 [TB] Driver San Fransisco BLES00891 External 9.05 1 [TB] Dungeon Siege III BLES01161 External 4.50 1 [TB] Dynasty Warriors Gundam 3 BLES01301 External 7.82 [TB] EyePet and Friends BCES00865 Internal 7.47 [TB] F.E.A.R. -

Dead-Island-Trailer-Gimmick

, February 18, 2011 [http://howtonotsuckatgamedesign.com/?p=1994] by Anjin Anhut. This Tarwtiecelet is f8iled under gLaimkee crit5icism and gam0 e semioSthicasrr.e 4 StumbleUpon If you liked the trailer and had strong connection to it, you probably shouldn’t read on. Or maybe you should do it. Don’t know. My intensions are not to talk people out of what they enjoy. If you had a certain feeling after the trailer, you wanna conserve, leave now. Being contrarian is not a hobby of mine. I love games and I want to add to the discourse and available information to help games grow. That’s why I teach classes in game design or write blog articles. But contributing to make games grow also means speaking up against the elements that in my opinion make games smaller than they actually need to be. Today I need to speak up against this: Is Dead Island what represents state of the art now? This goes allover twitter, facebook, commentary on video game sites and even among my friends. Are our collective expectations actually that low? No, that can not stand. Admittedly the Dead Island trailer has a very impressive production value and maybe I try to get the piano score via iTunes. Cool tune. I like it. But what is it we actually get to see? In my opinion the Dead Island trailer is an offensively mainstream piece of narration, lacking of ideas, lacking of balls, using the cheapest and most transparent gimmicks, to get credits for something it simply isn’t. Special. -

CLOSED CLOSED East Baton Rouge Parish Library Bluebonnet Regional

SUMMER 2018 Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 AY 27 28 29 30 31 1 June 2 June M SRP Kickoff Party- DIY Earbud Cases- Nintendo Switch CLOSED 2pm 3pm for Teens-2pm Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Snap Circuits- Perler Bead 3pm Bookmarks-3pm 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 CD Scratch Art- Life-sized Games Movie & Munchies UNE 3pm 3pm 2pm J 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Teen Video Game Teen Anime-3pm Day-3pm 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 NOVAC Film Camp NOVAC Film Camp NOVAC Film Camp NOVAC Film Camp NOVAC Film 2-5pm 2-5pm 2-5pm 2-5pm Camp-2-5pm Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hamilton Trivia- Teen Tech: Ozobots 3pm CLOSED 3pm 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Life-sized Board Tie-Dye T-shirts- Games-3pm 3pm 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 ULY Teen Video Game Teen Anime-3pm String Art-3pm J Day-3pm East Baton Rouge Parish Library 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Bluebonnet Regional Library Sheet Music Art- Makey Makey Movie & Munchies 3pm Banana Piano-3pm 2pm 9200 Bluebonnet Blvd, Baton Rouge, LA 70810 (225) 763-2270 29 30 31 1 2 3 4 SRP Pizza Party! 4pm The Teen/Young Adult Division of Bluebonnet Library serves tweens and teens ages 12—18 and/or grades 6—12. CLOSED WEDNESDAY, JULY 4th FOR INDEPENDENCE DAY HOLIDAY Libraries Rock! We invite you to rock with us and join our Teen Summer Reading Program. -

Nintendo Co., Ltd

Nintendo Co., Ltd. Financial Results Briefing for the Nine-Month Period Ended December 2013 (Briefing Date: 1/30/2014) Supplementary Information [Note] Forecasts announced by Nintendo Co., Ltd. herein are prepared based on management's assumptions with information available at this time and therefore involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties. Please note such risks and uncertainties may cause the actual results to be materially different from the forecasts (earnings forecast, dividend forecast and other forecasts). Nintendo Co., Ltd. Consolidated Statements of Income Transition million yen FY3/2010 FY3/2011 FY3/2012 FY3/2013 FY3/2014 Apr.-Dec.'09 Apr.-Dec.'10 Apr.-Dec.'11 Apr.-Dec.'12 Apr.-Dec.'13 Net sales 1,182,177 807,990 556,166 543,033 499,120 Cost of sales 715,575 487,575 425,064 415,781 349,825 Gross profit 466,602 320,415 131,101 127,251 149,294 (Gross profit ratio) (39.5%) (39.7%) (23.6%) (23.4%) (29.9%) Selling, general and administrative expenses 169,945 161,619 147,509 133,108 150,873 Operating income 296,656 158,795 -16,408 -5,857 -1,578 (Operating income ratio) (25.1%) (19.7%) (-3.0%) (-1.1%) (-0.3%) Non-operating income 19,918 7,327 7,369 29,602 57,570 (of which foreign exchange gains) (9,996) ( - ) ( - ) (22,225) (48,122) Non-operating expenses 2,064 85,635 56,988 989 425 (of which foreign exchange losses) ( - ) (84,403) (53,725) ( - ) ( - ) Ordinary income 314,511 80,488 -66,027 22,756 55,566 (Ordinary income ratio) (26.6%) (10.0%) (-11.9%) (4.2%) (11.1%) Extraordinary income 4,310 115 49 - 1,422 Extraordinary loss 2,284 33 72 402 53 Income before income taxes and minority interests 316,537 80,569 -66,051 22,354 56,936 Income taxes 124,063 31,019 -17,674 7,743 46,743 Income before minority interests - 49,550 -48,376 14,610 10,192 Minority interests in income -127 -7 -25 64 -3 Net income 192,601 49,557 -48,351 14,545 10,195 (Net income ratio) (16.3%) (6.1%) (-8.7%) (2.7%) (2.0%) - 1 - Nintendo Co., Ltd. -

Programme Edition

JOURNEE 13h00 - 18h00 WEEK END 14h00 - 19h00 JOURJOURJOUR Vendredi 18/12 - 19h00 Samedi 19/12 Dimanche 20/12 Lundi 21/12 Mardi 22/12 ThèmeThèmeThème Science Fiction Zelda & le J-RPG (Jeu de rôle Japonais) ArcadeArcadeArcade Strange Games AnimeAnimeAnime NES / Twin Famicom / MSXMSXMSX The Legend of Zelda Rainbow Islands Teenage Mutant Hero Turtles SC 3000 / Master System Psychic World Streets of Rage Rampage Super Nintendo Syndicate Zelda Link to the Past Turtles in Time + Sailor Moon Megadrive / Mega CD / 32X32X32X Alien Soldier + Robo Aleste Lunar 2 + Soleil Dynamite Headdy EarthWorm Jim + Rocket Knight Adventures Dragon Ball Z + Quackshot Nintendo 64 Star Wars Shadows of the Empire Furai no Shiren 2 Ridge Racer 64 Buck Bumble SaturnSaturnSaturn Deep Fear Shining Force III scénario 2 Sky Target Parodius Deluxe Pack + Virtual Hydlide Magic Knight Rayearth + DBZ Shinbutouden Playstation Final Fantasy VIII + Saga Frontier 2 Elemental Gearbolt + Gun Blade Arts Tobal n°1 Dreamcast Ghost Blade Spawn Twinkle Star Sprites Alice's Mom Rescue Gamecube F Zero GX Zelda Four Swords 4 joueurs Bleach Playstation 2 Earth Defense Force Code Age Commanders / Stella Deus Puyo Pop Fever Earth Defense Force Cowboy Bebop + Berserk XboxXboxXbox Panzer Dragoon Orta Out Run 2 Dead or Alive Xtreme Beach Volleyball Wii / Wii UWii U / Wii JPWii JP Fragile Dreams Xenoblade Chronicles X Devils Third Samba De Amigo Tatsunoko vs Capcom + The Skycrawlers Playstation 3 Guilty Gear Xrd Demon's Souls J Stars Victory versus + Catherine Kingdom Hearts 2.5 Xbox 360 / XBOX -

Nintendo Co., Ltd

Nintendo Co., Ltd. Financial Results Briefing for the Six-Month Period Ended September 2013 (Briefing Date: 10/31/2013) Supplementary Information [Note] Forecasts announced by Nintendo Co., Ltd. herein are prepared based on management's assumptions with information available at this time and therefore involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties. Please note such risks and uncertainties may cause the actual results to be materially different from the forecasts (earnings forecast, dividend forecast and other forecasts). Nintendo Co., Ltd. Semi-Annual Consolidated Statements of Income Transition million yen FY3/2010 FY3/2011 FY3/2012 FY3/2013 FY3/2014 Apr.-Sept.'09 Apr.-Sept.'10 Apr.-Sept.'11 Apr.-Sept.'12 Apr.-Sept.'13 Net sales 548,058 363,160 215,738 200,994 196,582 Cost of sales 341,759 214,369 183,721 156,648 134,539 Gross profit 206,298 148,791 32,016 44,346 62,042 (Gross profit ratio) (37.6%) (41.0%) (14.8%) (22.1%) (31.6%) Selling, general, and administrative expenses 101,937 94,558 89,363 73,506 85,321 Operating income 104,360 54,232 -57,346 -29,159 -23,278 (Operating income ratio) (19.0%) (14.9%) (-26.6%) (-14.5%) (-11.8%) Non-operating income 7,990 4,849 4,840 5,392 24,708 (of which foreign exchange gains) ( - ) ( - ) ( - ) ( - ) (18,360) Non-operating expenses 1,737 63,234 55,366 23,481 180 (of which foreign exchange losses) (664) (62,175) (52,433) (23,273) ( - ) Ordinary income 110,613 -4,152 -107,872 -47,248 1,248 (Ordinary income ratio) (20.2%) (-1.1%) (-50.0%) (-23.5%) (0.6%) Extraordinary income 4,311 190 50 - 1,421 Extraordinary loss 2,306 18 62 23 18 Income before income taxes and minority interests 112,618 -3,981 -107,884 -47,271 2,651 Income taxes 43,107 -1,960 -37,593 -19,330 2,065 Income before minority interests - -2,020 -70,290 -27,941 586 Minority interests in income 18 -9 -17 55 -13 Net income 69,492 -2,011 -70,273 -27,996 600 (Net income ratio) (12.7%) (-0.6%) (-32.6%) (-13.9%) (0.3%) - 1 - Nintendo Co., Ltd. -

Best Wishes to All of Dewey's Fifth Graders!

tiger times The Voice of Dewey Elementary School • Evanston, IL • Spring 2020 Best Wishes to all of Dewey’s Fifth Graders! Guess Who!? Who are these 5th Grade Tiger Times Contributors? Answers at the bottom of this page! A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R Tiger Times is published by the Third, Fourth and Fifth grade students at Dewey Elementary School in Evanston, IL. Tiger Times is funded by participation fees and the Reading and Writing Partnership of the Dewey PTA. Emily Rauh Emily R. / Levine Ryan Q. Judah Timms Timms Judah P. / Schlack Nathan O. / Wright Jonah N. / Edwards Charlie M. / Zhu Albert L. / Green Gregory K. / Simpson Tommy J. / Duarte Chaya I. / Solar Phinny H. Murillo Chiara G. / Johnson Talula F. / Mitchell Brendan E. / Levine Jojo D. / Colledge Max C. / Hunt Henry B. / Coates Eve A. KEY: ANSWER KEY: ANSWER In the News Our World............................................page 2 Creative Corner ..................................page 8 Sports .................................................page 4 Fun Pages ...........................................page 9 Science & Technology .........................page 6 our world Dewey’s first black history month celebration was held in February. Our former principal, Dr. Khelgatti joined our current Principal, Ms. Sokolowski, our students and other artists in poetry slams, drumming, dancing and enjoying delicious soul food. Spring 2020 • page 2 our world Why Potatoes are the Most Awesome Thing on the Planet By Sadie Skeaff So you know what the most awesome thing on the planet is, right????? Good, so you know that it is a potato. And I will tell you why the most awesome thing in the world is a potato, and you will listen. -

Super Smash Bros. Melee: an Interdisciplinary Esports Ethnography

"Melee is Broken": Super Smash Bros. Melee: An Interdisciplinary Esports Ethnography Abbie ·spoopy' Rappaport A Thesis In the Department of Humanities Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements F or the Degree of Master of Arts (Individualized Program) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada May 2020 © Abbie 'spoopy' Rappaport, 2020 CONCORDIA UNN ERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to ce1tify that the thesis prepared By: Abbie ''spoooopy' Rappaport Entitled: Mellee iis Brrokkeenn”":: Supperr Smassh Bros.. Melleee:: An Interrdiisscciipplliinnary Esporrttss Etthnography and submitted in prutial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Indiivviiddualized Mastterss (IINDI MA)) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standru·ds with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: Rachel Berger Chair Darrrren Werrsshllerr Examiner Barrtt Siimon Examiner Pipppin Barr Thesis Supervisor(s) Darren Wershlerr,, Bart Simon,, Piippppin Baarrrr Approved by Rachel Berger Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director Effrosyni Diamantoudi, Dean, Date iii Abstract "Melee is Broken": Super Smash Bros. Melee: An Interdisciplinary Esports Ethnography Abbie 'spoopy' Rappaport This work presents a qualitative analysis of the esports community that plays and watches Super Smash Bros. Melee (SSBM) , a platform-based fighting game released for the Nintendo GameCube in 2001. SSBM is unusual as an esport for the way that it is built on a grass-roots foundation shaped by players (rather than the game's developers) and is contingent on the continued use of residual media objects, specifically the CRT television, Nintendo GameCube and Wii console coupled with the restraints of analog signal processing. SSBM players show particular dedication to dominant community practices like strict tournament rules and settings, shared use of dialect/nomenclatures, mode of play and so on, which are derived from, embedded in, and reinforced by specific hardware and software objects. -

Catalogo Nintendo Switch

Inverno 2020/2021 OMAGGIO Che cos'è Nintendo Switch? Nintendo Switch è una console per giocare dove, quando e con chi vuoi La famiglia Nintendo Switch comprende due console Nintendo Switch – pensata per giocare a casa oppure dove vuoi Tre modi di giocare Modalità TV Modalità da tavolo Modalità portatile p.06 ~ p.09 Nintendo Switch Lite pensata per giocare in mobilità p.10 ~ p.11 Dove, quando e con chi vuoi. Tre modalità 1 Modalità TV Nintendo Switch consente tre modalità di gioco. Inserisci Nintendo Switch nella base e gioca in HD sulla tua TV. Collegarlo alla TV è facile La console si accende appena la rimuovi Adattatore AC dalla base. Porta la console con te e Nintendo Switch continua a giocare in modalità portatile. Cavo HDMI Basta collegare l'adattatore AC e il cavo HDMI inclusi nella confezione a ogni uscita. Dove, quando e con chi vuoi. Tre modalità 2 Usa lo stand integrato e condividi il divertimento Modalità da tavolo con un gioco multiplayer. Inserendo i due Joy-Con nell'impugnatura Joy-Con Joy-Con ottieni un controller tradizionale. Nintendo Switch dispone di Senza l'impugnatura, ogni Joy-Con è un controller due controller, uno per lato, che indipendente. funzionano anche insieme. Nintendo Switch consente tre modalità di gioco. Tre modalità 3 Collega i controller Joy-Con alla console e Modalità portatile gioca dove vuoi. Nintendo Switch Lite – Nintendo Switch Lite è una console compatta, leggera e con comandi integrati. pensata per giocare in mobilità Nintendo Switch Lite è compatibile con tutti i software per Nintendo Switch che possono essere giocati in modalità portatile. -

Manual Dead Island Riptide PC

© Copyright 2013 and Published by Deep Silver, a division of Koch Media GmbH, Gewerbegebiet 1, 6604 Höfen, Austria. Developed 2013, Techland Sp. z o.o., Poland. © Copyright 2013, Chrome Engine, Techland Sp. z o.o. All rights reserved. 1550110 Manual Dear Customer, Table of Contents Congratulations on purchasing this product from our company. We and the developers have done our best to provide you with Installation ....................................................................... 3 polished, interesting and entertaining software. We hope that it meets your expectations, and we would be pleased if you recommended it to Game Controls ................................................................ 3 your friends. Introduction to the Story .................................................... 4 If you are interested in our company’s other products or would like to Characters ...................................................................... 4 receive general information about our group of companies, please visit one of our websites: Character Info ................................................................. 4 www.kochmedia.com Character Selection .......................................................... 7 www.deepsilver.com Choosing a Character ...................................................... 7 We hope you enjoy your Koch Media product! Distribute Skill Points ......................................................... 8 Sincerely, The Koch Media Team Character Development ...................................................