DE Andradmathesis.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republican SINN FÉIN Poblachtach Theobald Wolfe Tone Commemoration Bodenstown, County Kildare

Republican SINN FÉIN Poblachtach Theobald Wolfe Tone Commemoration Bodenstown, County Kildare 2000 ‘Former Republicans have been bought off with palliatives’ Cathleen Knowles McGuirk, Vice President Republican Sinn Féin delivered the oration at the grave of Theobald Wolfe Tone, the founder of Irish Republicanism, on Sunday, June 11 in Bodenstown cemetery, outside Sallins, Co Kildare. The large crowd, led by a colour party carrying the National Flag and contingents of Cumann na mBan and Na Fianna Éireann, as well as the General Tom Maguire Flute Band from Belfast marched the three miles from Sallins Village to the grave of Wolfe Tone at Bodenstown. Contingents from all over Ireland as well as visitors from Britain and the United States took part in the march, which was marshalled by Seán Ó Sé, Dublin. At the graveside of Wolfe Tone the proceedings were chaired by Seán Mac Oscair, Fermanagh, Ard Chomhairle, Republican Sinn Féin who said he was delighted to see the large number of young people from all over Ireland in attendance this year. The ceremony was also addressed by Peig Galligan on behalf of the National Graves Association, who care for Ireland’s patriot graves. Róisín Hayden read a message from Republican Sinn Féin Patron, George Harrison, New York. Republican SINN FÉIN Poblachtach Theobald Wolfe Tone Commemoration Bodenstown, County Kildare “A chairde, a comrádaithe agus a Phoblactánaigh, tá an-bhród orm agus tá sé d’onóir orm a bheith anseo inniu ag uaigh Thiobóid Wolfe Tone, Athair an Phoblachtachais in Éirinn. Fellow Republicans, once more we gather here in Bodenstown churchyard at the grave of Theobald Wolfe Tone, the greatest of the Republican leaders of the 18th century, the most visionary Irishman of his day, and regarded as the “Father of Irish Republicanism”. -

FLAG of IRELAND - a BRIEF HISTORY Where in the World

Part of the “History of National Flags” Series from Flagmakers FLAG OF IRELAND - A BRIEF HISTORY Where In The World Trivia The Easter Rising Rebels originally adopted the modern green-white-orange tricolour flag. Technical Specification Adopted: Officially 1937 (unofficial 1916 to 1922) Proportion: 1:2 Design: A green, white and orange vertical tricolour. Colours: PMS – Green: 347, Orange: 151 CMYK – Green: 100% Cyan, 0% Magenta, 100% Yellow, 45% Black; Orange: 0% Cyan, 100% Magenta 100% Yellow, 0% Black Brief History The first historical Flag was a banner of the Lordship of Ireland under the rule of the King of England between 1177 and 1542. When the Crown of Ireland Act 1542 made Henry VII the king of Ireland the flag became the Standard of the Kingdom of Ireland, a blue field featuring a gold harp with silver strings. The Banner of the Lordship of Ireland The Royal Standard of the Kingdom of Ireland (1177 – 1541) (1542 – 1801) When Ireland joined with Great Britain to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in 1801, the flag was replaced with the Flag of the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. This was flag of the United Kingdom defaced with the Coat of Arms of Ireland. During this time the Saint Patrick’s flag was also added to the British flag and was unofficially used to represent Northern Ireland. The Flag of the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland The Cross of Saint Patrick (1801 – 1922) The modern day green-white-orange tricolour flag was originally used by the Easter Rising rebels in 1916. -

Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Cultural Exchange: from Medieval

Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Volume 1: Issue 1 Cultural Exchange: from Medieval to Modernity AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies JOURNAL OF IRISH AND SCOTTISH STUDIES Volume 1, Issue 1 Cultural Exchange: Medieval to Modern Published by the AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies at the University of Aberdeen in association with The universities of the The Irish-Scottish Academic Initiative and The Stout Research Centre Irish-Scottish Studies Programme Victoria University of Wellington ISSN 1753-2396 Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Issue Editor: Cairns Craig Associate Editors: Stephen Dornan, Michael Gardiner, Rosalyn Trigger Editorial Advisory Board: Fran Brearton, Queen’s University, Belfast Eleanor Bell, University of Strathclyde Michael Brown, University of Aberdeen Ewen Cameron, University of Edinburgh Sean Connolly, Queen’s University, Belfast Patrick Crotty, University of Aberdeen David Dickson, Trinity College, Dublin T. M. Devine, University of Edinburgh David Dumville, University of Aberdeen Aaron Kelly, University of Edinburgh Edna Longley, Queen’s University, Belfast Peter Mackay, Queen’s University, Belfast Shane Alcobia-Murphy, University of Aberdeen Brad Patterson, Victoria University of Wellington Ian Campbell Ross, Trinity College, Dublin The Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies is a peer reviewed journal, published twice yearly in September and March, by the AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies at the University of Aberdeen. An electronic reviews section is available on the AHRC Centre’s website: http://www.abdn.ac.uk/riiss/ahrc- centre.shtml Editorial correspondence, including manuscripts for submission, should be addressed to The Editors,Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies, AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies, Humanity Manse, 19 College Bounds, University of Aberdeen, AB24 3UG or emailed to [email protected] Subscriptions and business correspondence should be address to The Administrator. -

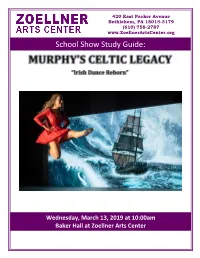

School Show Study Guide

420 East Packer Avenue Bethlehem, PA 18015-3179 (610) 758-2787 www.ZoellnerArtsCenter.org School Show Study Guide: Wednesday, March 13, 2019 at 10:00am Baker Hall at Zoellner Arts Center USING THIS STUDY GUIDE Dear Educator, On Wednesday, March 13, your class will attend a performance by Murphy’s Celtic Legacy, at Lehigh University’s Zoellner Arts Center in Baker Hall. You can use this study guide to engage your students and enrich their Zoellner Arts Center field trip. Materials in this guide include information about the performance, what you need to know about coming to a show at Zoellner Arts Center and interesting and engaging activities to use in your classroom prior to and following the performance. These activities are designed to go beyond the performance and connect the arts to other disciplines and skills including: Dance Culture Expression Social Sciences Teamwork Choreography Before attending the performance, we encourage you to: Review the Know before You Go items on page 3 and Terms to Know on pages 9. Learn About the Show on pages 4. Help your students understand Ireland on pages 11, the Irish dance on pages 17 and St. Patrick’s Day on pages 23. Engage your class the activity on pages 25. At the performance, we encourage you to: Encourage your students to stay focused on the performance. Encourage your students to make connections with what they already know about rhythm, music, and Irish culture. Ask students to observe how various show components, like costumes, lights, and sound impact their experience at the theatre. After the show, we encourage you to: Look through this study guide for activities, resources and integrated projects to use in your classroom. -

1. Provide an Introduction and Overview of Your Study Abroad Experience

1. Provide an introduction and overview of your study abroad experience. I received the wonderful and unique experience of studying abroad at the University of Limerick Ireland, and upon my journey; I met new friends from all over the world, gained insight into not only the culture of Ireland, but also cultures from around the world, and discovered my true independence and strength. I joined the Outdoor Pursuits club and the International Society at the University of Limerick and these clubs aided in my friendship making and advanced cultural knowledge. Through these clubs, I was able to travel around Ireland not only to the cities, but also to the farmland and the country side as I hiked through mountains and valleys. Studying abroad in Ireland was a fantastic and educational experience. 2. Using one to two examples, explain how your study abroad experience advanced your knowledge and understanding of the world’s diverse cultures, environments, practices and/or values. Through my curiosity of culture and people and the incredible friends I made, I learned about not only the Irish culture, but also was able to gain some knowledge of Grecian, German, French, Spanish, and Swedish cultures. My closest friends were from these various countries and allowed me to ask them about the different aspects of their cultures and lives back at their home. During my time in Ireland, I was also able to stay a full week with an Irish family when my father came to visit. Through them I discovered many Irish ways and culture. I was able to make a true Irish breakfast with them as well as attend an Irish church, which is a big cultural thing for Irish families. -

Milford Mills and the Creation of a Gentry Powerbase: the Alexanders of Co

Milford Mills and the creation of a gentry powerbase: the Alexanders of Co. Carlow, 1790-1870 by Shay Kinsella, B.A. A thesis submitted for the degree of PhD Supervisor: Dr Carla King Department of History St. Patrick’s College, Drumcondra Dublin City University June 2015 I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) is entirely my own work and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: ID No.: 11262834 Date: 30 June 2015 Contents List of Tables and Figures....................................................................................................................... iii Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................................v Abstract ................................................................................................................................................ vi Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................... vii Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... ix Chapter 1 The origins of the Milford Alexanders .................................................................. 1 ✓ i. Alexander origins in Ireland, 1610-1736 ii. -

In Humberts Footsteps 1798 & the Year of the French

In Humberts Footsteps 1798 & the Year of the French Humbert General Jean Joseph Amable Humbert was 1792 joined the 13th Battalion of the born at “La Coare,” a substantial farm in Vosges and was soon elected captain. On the parish of Saint -Nabord, near 9 April, 1794, he was promoted to Remiremont in the Vosges district of Brigadier General and distinguished France, on 22 August, 1767. His parents, himself in the horrific “War in the Jean Joseph Humbert and Catherine Rivat Vendeé”, a coastal region in western died young, and Humbert and his sister, France. It was during this campaign that Marie Anne, were raised by their Humbert first came under the influence of influential grandmother. one of the most celebrated young French commanders, General Lazare Hoche. As a youth Humbert worked in various jobs before setting up a very profitable In 1796, he was part of the 15,000 strong business selling animal skins to the great French expedition commanded by Hoche glove and legging factories of Grenoble which failed to land at Bantry Bay, and Lyon. In 1789, following the fall of the although folklore maintains that Humbert Bastille, he abandoned his business and came ashore on a scouting mission. Two joined the army, enlisting in one of the first years later, he was once again in Ireland, volunteer battalions. Later he enrolled as a this time at the head of his own small sergeant in the National Guard and in expedition. “By a forced march he crossed twenty English miles of bog and mountain, by a road hitherto considered impracticable-reached the royalist position-and at noon on Monday had completely routed a well-appointed army, and seized the town of Castlebar. -

Republic of Ireland. Wikipedia. Last Modified

Republic of Ireland - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia What links here Related changes Upload file Special pages Republic of Ireland Permanent link From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page information Data item This article is about the modern state. For the revolutionary republic of 1919–1922, see Irish Cite this page Republic. For other uses, see Ireland (disambiguation). Print/export Ireland (/ˈaɪərlənd/ or /ˈɑrlənd/; Irish: Éire, Ireland[a] pronounced [ˈeː.ɾʲə] ( listen)), also known as the Republic Create a book Éire of Ireland (Irish: Poblacht na hÉireann), is a sovereign Download as PDF state in Europe occupying about five-sixths of the island Printable version of Ireland. The capital is Dublin, located in the eastern part of the island. The state shares its only land border Languages with Northern Ireland, one of the constituent countries of Acèh the United Kingdom. It is otherwise surrounded by the Адыгэбзэ Atlantic Ocean, with the Celtic Sea to the south, Saint Flag Coat of arms George's Channel to the south east, and the Irish Sea to Afrikaans [10] Anthem: "Amhrán na bhFiann" Alemannisch the east. It is a unitary, parliamentary republic with an elected president serving as head of state. The head "The Soldiers' Song" Sorry, your browser either has JavaScript of government, the Taoiseach, is nominated by the lower Ænglisc disabled or does not have any supported house of parliament, Dáil Éireann. player. You can download the clip or download a Aragonés The modern Irish state gained effective independence player to play the clip in your browser. from the United Kingdom—as the Irish Free State—in Armãneashce 1922 following the Irish War of Independence, which Arpetan resulted in the Anglo-Irish Treaty. -

William Butler Yeats: Nationalism, Mythology, and the New Irish Tradition

Salem State University Digital Commons at Salem State University Honors Theses Student Scholarship 2015-5 William Butler Yeats: Nationalism, Mythology, and the New Irish Tradition Samuel N. Welch IV Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salemstate.edu/honors_theses Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Welch, Samuel N. IV, "William Butler Yeats: Nationalism, Mythology, and the New Irish Tradition" (2015). Honors Theses. 63. https://digitalcommons.salemstate.edu/honors_theses/63 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Digital Commons at Salem State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at Salem State University. 1 WILLIAM BUTLER YEATS: NATIONALISM, MYTHOLOGY, AND THE NEW IRISH TRADITION Honors Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Bachelor of English In the College of Arts and Sciences at Salem State University By Samuel N. Welch IV Dr. Richard Elia Faculty Advisor Department of English *** Commonwealth Honors Program Salem State University 2015 i Table of Contents Page Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………...ii Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………….iii The Purpose and Methods of Yeats……………………………………………………………..1 Finding a Voice: The Wanderings of Oisin and The Rose………………………………………3 The Search for Ireland: The Wind Among the Reeds……………………………………………9 The Later Years: To a Wealthy Man . and Under Ben Bulben……………………………….12 Conclusions……………………………………………………………………………………..16 Works Cited……………………………………………………………………………………..17 ii Acknowledgements I would firstly like to express my sincerest thanks to Dr. Richard Elia of the Salem State University English department for all of the encouragement and guidance he has given me towards completing this project. -

The Society of United Irishmen and the Rebellion of 1798

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1988 The Society of United Irishmen and the Rebellion of 1798 Judith A. Ridner College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Ridner, Judith A., "The Society of United Irishmen and the Rebellion of 1798" (1988). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625476. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-d1my-pa56 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SOCIETY OF UNITED IRISHMEN AND THE REBELLION OF 1798 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Judith Anne Ridner 1988 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts *x CXm j UL Author Approved, May 1988 Thomas Sheppard Peter Clark James/McCord TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS................................................. iv ABSTRACT................................. V CHAPTER I. THE SETTING.............. .................................. 2 CHAPTER II. WE WILL NOT BUY NOR BORROW OUR LIBERTY.................... 19 CHAPTER III. CITIZEN SOLDIERS, TO ARMS! ........................... 48 CHAPTER IV. AFTERMATH................................................. 76 BIBLIOGRAPHY........................................................... 87 iii ABSTRACT The Society of United Irishmen was one of many radical political clubs founded across the British Isles in the wake of the American and French Revolutions. -

The NOLAN CLAN and the 1916 EASTER RISING

TTHHEE NNOOLLAANN The Newslletter of the O’’Nollan Cllan Famiilly Associiatiion March 2016 Issue 26 CONTENTS 2 In Brief … 3 Thomas Nowlan of Dublin, Esq. 9 The Long Road to Freedom 16 Nolan Clan & the 1916 Easter Rising 20 Miscellaneous News Items 21 Membership Application /Renewal Form Happy St Patrick’s Day O’Nolan Clan In Brief … Family Association This year’s issue of the Nolan Clan Newsletter has as its main theme the 1916 Easter Rising starting with a special cover which incorporates key wording from Chief – Christopher Nolan the Proclamation of Irish Freedom read out loud on Easter Monday 1916. 67 Commons Road Clermont, New York 12526 United States of America The first article, co-written by Paula Edgar and Debbie Dunne, provides an intimate TEL: +1 (518) 755-5089 look at life in the mid-1800s painting a portrait of a Dublin businessman, Thomas chrisanolan3 Nowlan, Esq., who despite challenging times prospered. His shop was just across @gmail.com from the General Post Office (GPO) which would later become the focal point for Tánaiste – Catherina the Easter Rising. By a strange coincidence, Thomas has another connection to the O’Brien Ballytarsna, Nurney, Co. Easter Rising, not the event itself back in 1916, but its 100th year commemoration Carlow Republic of Ireland on Easter Monday this year. As it happens part of Thomas’ lands back in the mid- TEL: +353 (59) 9727377 or cell +353 (87) 1800s (approx. 100 acres) now form part of the Fairyhouse Racecourse in County 9723024 Meath where, as for every year, on Easter Sunday, the Irish Grand National, obrienecat “The race of the people”, will be run. -

Per Cent for Arts Commission M11 Gorey to Enniscorthy PPP Scheme

Per Cent for Arts Commission M11 Gorey to Enniscorthy PPP Scheme Artists Brief: Supplementary Information County Wexford is located in the southeast corner of Ireland. The County has four main towns - Wexford, Enniscorthy, Gorey and New Ross - with an overall population of 149,722 (CSO population figures 2016). County Wexford enjoys a rare mix of mountains, valleys, rivers, slob lands, flora, fauna and breath-taking beaches along its 270km of coastline. The county is bounded by the sea on two sides – on the south by the Atlantic Ocean and on the east by St. George’s Channel and the Irish Sea. The River Barrow forms its western boundary and the river Slaney which rises in the Wicklow mountains runs south through Enniscorthy town before entering the Irish Sea at the estuary in Wexford town. The Blackstairs Mountains form part of the boundary to the north, as do the southern edges of the Wicklow Mountains. The adjoining counties are Waterford, Kilkenny, Carlow and Wicklow. The Local Authority for the county is Wexford County Council (Comhairle Contae Loch Garman) which has 34 elected members and is divided into the four municipal districts of Gorey, Enniscorthy, New Ross and Wexford Borough. The Council is responsible for a range of services including housing and community, roads and transportation, planning and development, arts amenity culture and environment The M11 Gorey – Enniscorthy PPP Scheme passes primarily through Enniscorthy and Gorey Municipal Districts which including many rural town lands and villages as well as the bigger towns of Enniscorthy, Ferns and Camolin. History An age-old gateway into Ireland, County Wexford is steeped in history dating back to the Stone Age over 6,000 years ago.