Water in North America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nick Walker, Ph.D. ([email protected]) Kim De Mutsert, Andy Dolloff, Vivek Prasad, A

Nick Walker, Ph.D. ([email protected]) Kim De Mutsert, Andy Dolloff, Vivek Prasad, A. Alonso Aguirre Joint Meeting of the American Eel Interest Group and the Sturgeon Interest Group December 12th, 2019 Why eels? Found in more habitats than another fish. Ideal for studies across a wide geographic area. Everyone talks about interconnectedness of ecosystems – eels live it. Connections with humans throughout history, opportunities for citizen science. A fish that can bring people back to nature. Adapted from Tsukamoto (2014). Fig. 1. American Eel sampling events Objectives Objective was to build a model of the subwatersheds of the Chesapeake Bay using a Digital Elevation Model (DEM); then add eel data, dams and land use. Goal was to create color‐coded maps of where eels are doing well and areas that might be prioritized for conservation. This study is follow‐up to our previous work on American Eel demographics in the Chesapeake Bay. Methods –Data collection Eel data from VA DGIF, MD DNR, USFWS et al. Elevation data from ASTER DEM (plus river data from USGS small scale maps). Dam data from The Nature Conservancy. Land use from Université Catholique de Louvain in Belgium. Sources limited by 2019 government shutdown. Methods Delineating streams and watersheds in ArcGIS: Load ASTER tiles (30x30m resolution; 20 tiles for study area). Fill, Flow direction and Flow Accumulation on each tile. Raster calculator: SetNull(“bay_flowac” < 27778,1) This sets minimum threshold to 25 km2 (or 25*106)/(302) Stream Link, Stream Order and Stream to Feature on each tile. Watersheds split along mainstem every 50 km. -

Maryland's Wildland Preservation System “The Best of the Best”

Maryland’s Wildland Preservation System “The“The Best Best ofof thethe Best” Best” What is a Wildland? Natural Resources Article §5‐1201(d): “Wildlands” means limited areas of [State‐owned] land or water which have •Retained their wilderness character, although not necessarily completely natural and undisturbed, or •Have rare or vanishing species of plant or animal life, or • Similar features of interest worthy of preservation for use of present and future residents of the State. •This may include unique ecological, geological, scenic, and contemplative recreational areas on State lands. Why Protect Wildlands? •They are Maryland’s “Last Great Places” •They represent much of the richness & diversity of Maryland’s Natural Heritage •Once lost, they can not be replaced •In using and conserving our State’s natural resources, the one characteristic more essential than any other is foresight What is Permitted? • Activities which are consistent with the protection of the wildland character of the area, such as hiking, canoeing, kayaking, rafting, hunting, fishing, & trapping • Activities necessary to protect the area from fire, animals, insects, disease, & erosion (evaluated on a case‐by case basis) What is Prohibited? Activities which are inconsistent with the protection of the wildland character of the area: permanent roads structures installations commercial enterprises introduction of non‐native wildlife mineral extraction Candidate Wildlands •23 areas •21,890 acres •9 new •13,128 acres •14 expansions Map can be found online at: http://dnr.maryland.gov/land/stewardship/pdfs/wildland_map.pdf -

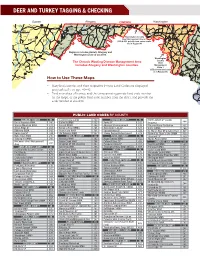

Deer and Turkey Tagging & Checking

DEER AND TURKEY TAGGING & CHECKING Garrett Allegany CWDMA Washington Frederick Carroll Baltimore Harford Lineboro Maryland Line Cardiff Finzel 47 Ellerlise Pen Mar Norrisville 24 Whiteford ysers 669 40 Ringgold Harney Freeland 165 Asher Youghiogheny 40 Ke 40 ALT Piney Groev ALT 68 615 81 11 Emmitsburg 86 ge Grantsville Barrellville 220 Creek Fairview 494 Cearfoss 136 136 Glade River aLke Rid 546 Mt. avSage Flintstone 40 Cascade Sabillasville 624 Prospect 68 ALT 36 itts 231 40 Hancock 57 418 Melrose 439 Harkins Corriganville v Harvey 144 194 Eklo Pylesville 623 E Aleias Bentley Selbysport 40 36 tone Maugansville 550 419410 Silver Run 45 68 Pratt 68 Mills 60 Leitersburg Deep Run Middletown Springs 23 42 68 64 270 496 Millers Shane 646 Zilhman 40 251 Fountain Head Lantz Drybranch 543 230 ALT Exline P 58 62 Prettyboy Friendsville 638 40 o 70 St. aulsP Union Mills Bachman Street t Clear 63 491 Manchester Dublin 40 o Church mithsburg Taneytown Mills Resevoir 1 Aviltn o Eckhart Mines Cumberland Rush m Spring W ilson S Motters 310 165 210 LaVale a Indian 15 97 Rayville 83 440 Frostburg Glarysville 233 c HagerstownChewsville 30 er Springs Cavetown n R 40 70 Huyett Parkton Shawsville Federal r Cre Ady Darlingto iv 219 New Little 250 iv Cedar 76 140 Dee ek R Ridgeley Twiggtown e 68 64 311 Hill Germany 40 Orleans r Pinesburg Keysville Mt. leasP ant Rocks 161 68 Lawn 77 Greenmont 25 Blackhorse 55 White Hall Elder Accident Midlothian Potomac 51 Pumkin Big pringS Thurmont 194 23 Center 56 11 27 Weisburg Jarrettsville 136 495 936 Vale Park Washington -

Pocomoke Floodplain Restoration 1,193 839

Pocomoke Floodplain Restoration Freeing a Trapped River © Kent Mason 75 Years of Channelization Pocomoke is an Algonquin word meaning “black water.” The heavy vegetation along Key Accomplishments*: the river’s swampy banks decomposes as organic matter into the river, coloring the water an inky black. The river was a key trading route for Native Americans for at least acres of public lands 300 years before English settlers arrived. In the late 1930s and early 1940s, the river 1,193 restored was dredged and channelized, and its banks clear-cut of timber, with the objective of eliminating the flooding of farmland that had been established within the river’s acres of private lands watershed. What wasn’t understood at the time was the important role that the 839 restored river’s natural flooding cycles play in the health of the surrounding cypress swamp, which is home to a biodiverse ecosystem. Recent scientific studies led by The Nature Conservancy and the US Geological Survey revealed that a restored Pocomoke acres of private lands floodplain would have a significant additional benefit — water that flows through the planned for future 552 restoration river’s swampy floodplain is naturally filtered, removing nutrients and sediment from upstream agricultural runoff, before flowing downstream into the Chesapeake Bay. *Results reported as of May 2017 Freeing a Trapped River In 2012, The Nature Conservancy and the Maryland Department of Natural Resources joined the Pocomoke floodplain restoration effort being led by the US Fish and Wildlife Service and Natural Resources Conservation Service. The restoration of the Pocomoke floodplain is one of the largest ecological restoration efforts in Maryland’s history. -

Maryland Stream Waders 10 Year Report

MARYLAND STREAM WADERS TEN YEAR (2000-2009) REPORT October 2012 Maryland Stream Waders Ten Year (2000-2009) Report Prepared for: Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 1-877-620-8DNR (x8623) [email protected] Prepared by: Daniel Boward1 Sara Weglein1 Erik W. Leppo2 1 Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 2 Tetra Tech, Inc. Center for Ecological Studies 400 Red Brook Boulevard, Suite 200 Owings Mills, Maryland 21117 October 2012 This page intentionally blank. Foreword This document reports on the firstt en years (2000-2009) of sampling and results for the Maryland Stream Waders (MSW) statewide volunteer stream monitoring program managed by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources’ (DNR) Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division (MANTA). Stream Waders data are intended to supplementt hose collected for the Maryland Biological Stream Survey (MBSS) by DNR and University of Maryland biologists. This report provides an overview oft he Program and summarizes results from the firstt en years of sampling. Acknowledgments We wish to acknowledge, first and foremost, the dedicated volunteers who collected data for this report (Appendix A): Thanks also to the following individuals for helping to make the Program a success. • The DNR Benthic Macroinvertebrate Lab staffof Neal Dziepak, Ellen Friedman, and Kerry Tebbs, for their countless hours in -

A Brief History of Worcester County (PDF)

Contents Worcester’s Original Locals ................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Native American Names ...................................................................................................................................................................... 5 From Colony To Free State ................................................................................................................................................................. 6 A Divided Land: Civil War .................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Storm Surges & Modern Times ........................................................................................................................................................... 8 Our Historic Towns .............................................................................................................................................................................. 9 Berlin ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 9 Ocean City .................................................................................................................................................................................. 10 Ocean Pines -

Organic Compounds and Trace Elements in the Pocomoke River and Tributaries, Maryland

Organic Compounds and Trace Elements in the Pocomoke River and Tributaries, Maryland Open-File Report 99-57 (Revised January 2000) In cooperation with George Mason University and Maryland Department of the Environment U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Organic Compounds and Trace Elements in the Pocomoke River and Tributaries, Maryland By Cherie V. Miller, Gregory D. Foster, Thomas B. Huff, and John R. Garbarino Open-File Report 99-57 (Revised January 2000) In cooperation with George Mason University and Maryland Department of the Environment Baltimore, Maryland 2000 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY U.S. Department of the Interior BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Charles G. Groat, Director The use of trade, product, or firm names in this report is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. For additional information contact: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey 8987 Yellow Brick Road Baltimore, MD 21237 Copies of this report can be purchased from: U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services Box 25286 Denver, CO 80225-0286 CONTENTS Abstract.........................................................................................................................................1 Introduction...................................................................................................................................1 Background ......................................................................................................................2 -

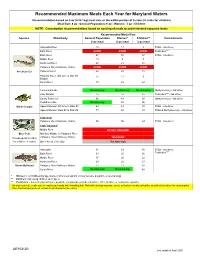

Recommended Maximum Fish Meals Each Year For

Recommended Maximum Meals Each Year for Maryland Waters Recommendation based on 8 oz (0.227 kg) meal size, or the edible portion of 9 crabs (4 crabs for children) Meal Size: 8 oz - General Population; 6 oz - Women; 3 oz - Children NOTE: Consumption recommendations based on spacing of meals to avoid elevated exposure levels Recommended Meals/Year Species Waterbody General PopulationWomen* Children** Contaminants 8 oz meal 6 oz meal 3 oz meal Anacostia River 15 11 8 PCBs - risk driver Back River AVOID AVOID AVOID Pesticides*** Bush River 47 35 27 PCBs - risk driver Middle River 13 9 7 Northeast River 27 21 16 Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor AVOID AVOID AVOID American Eel Patuxent River 26 20 15 Potomac River (DC Line to MD 301 1511 9 Bridge) South River 37 28 22 Centennial Lake No Advisory No Advisory No Advisory Methylmercury - risk driver Lake Roland 12 12 12 Pesticides*** - risk driver Liberty Reservoir 96 48 48 Methylmercury - risk driver Tuckahoe Lake No Advisory 93 56 Black Crappie Upper Potomac: DC Line to Dam #3 64 49 38 PCBs - risk driver Upper Potomac: Dam #4 to Dam #5 77 58 45 PCBs & Methylmercury - risk driver Crab meat Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor 96 96 24 PCBs - risk driver Crab "mustard" Middle River DO NOT CONSUME Blue Crab Mid Bay: Middle to Patapsco River (1 meal equals 9 crabs) Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor "MUSTARD" (for children: 4 crabs ) Other Areas of the Bay Eat Sparingly Anacostia 51 39 30 PCBs - risk driver Back River 33 25 20 Pesticides*** Middle River 37 28 22 Northeast River 29 22 17 Brown Bullhead Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor 17 13 10 South River No Advisory No Advisory 88 * Women = of childbearing age (women who are pregnant or may become pregnant, or are nursing) ** Children = all young children up to age 6 *** Pesticides = banned organochlorine pesticide compounds (include chlordane, DDT, dieldrin, or heptachlor epoxide) As a general rule, make sure to wash your hands after handling fish. -

Watersheds.Pdf

Watershed Code Watershed Name 02130705 Aberdeen Proving Ground 02140205 Anacostia River 02140502 Antietam Creek 02130102 Assawoman Bay 02130703 Atkisson Reservoir 02130101 Atlantic Ocean 02130604 Back Creek 02130901 Back River 02130903 Baltimore Harbor 02130207 Big Annemessex River 02130606 Big Elk Creek 02130803 Bird River 02130902 Bodkin Creek 02130602 Bohemia River 02140104 Breton Bay 02131108 Brighton Dam 02120205 Broad Creek 02130701 Bush River 02130704 Bynum Run 02140207 Cabin John Creek 05020204 Casselman River 02140305 Catoctin Creek 02130106 Chincoteague Bay 02130607 Christina River 02050301 Conewago Creek 02140504 Conococheague Creek 02120204 Conowingo Dam Susq R 02130507 Corsica River 05020203 Deep Creek Lake 02120202 Deer Creek 02130204 Dividing Creek 02140304 Double Pipe Creek 02130501 Eastern Bay 02141002 Evitts Creek 02140511 Fifteen Mile Creek 02130307 Fishing Bay 02130609 Furnace Bay 02141004 Georges Creek 02140107 Gilbert Swamp 02130801 Gunpowder River 02130905 Gwynns Falls 02130401 Honga River 02130103 Isle of Wight Bay 02130904 Jones Falls 02130511 Kent Island Bay 02130504 Kent Narrows 02120201 L Susquehanna River 02130506 Langford Creek 02130907 Liberty Reservoir 02140506 Licking Creek 02130402 Little Choptank 02140505 Little Conococheague 02130605 Little Elk Creek 02130804 Little Gunpowder Falls 02131105 Little Patuxent River 02140509 Little Tonoloway Creek 05020202 Little Youghiogheny R 02130805 Loch Raven Reservoir 02139998 Lower Chesapeake Bay 02130505 Lower Chester River 02130403 Lower Choptank 02130601 Lower -

Somerset County, Maryland

- H L 350 350 S S t t e e o o s s m r m r e e SSoommeerrsseett 350350 H L - Annemessex River landscape, Aerial photograph by Joey Gardner, 2016 Native Americans, Explorers and Settlement of Somerset n August 22, 1666, Cecil Calvert, Lord proprietor of the province of Maryland, authorized legislation creating OSomerset County, and 350 years later in this anniversary year, we look back as well as forward in celebration to honor and cherish our past as we continue to live here in the present and future. Somerset’s first inhabitants, however, were the native tribes of the lower Eastern Shore. Native American occupation of the region dates back thousands of years; its earliest inhabitants occupied a landscape far different than today with much lower sea levels. Spanning over fifteen to twenty thousand years, native American habitation matured from hunter-gathers to settled communities of tribes who resided along the region’s A characteristic Paleo-Indian fluted numerous waterways, many of which still carry their names. The Pocomoke, Manokin, projectile point from Maryland’s Eastern Annemessex, Monie and Wicomico waterways are named for these native tribes. Shore, Nancy Kurtz. Native American occupation is also represented by the thousands of artifacts that turn up in the soil, or through the written historical record as Anglo-American explorers, traders and ultimately settlers interacted with them across the peninsula. One of the earliest explorers to leave a written record of his visit, describing the local inhabitants as well as their activities was Giovanni da Verrazano, who, during the 1520s, traveled along what later became Somerset County. -

Area's #1 Fishing & Hunting Outfitter

Dear Angler: Here in Maryland, we need only look to our State Seal — depicting the fisherman and the ploughman — for proof that fishing really is part of our heritage. It’s a fun, affordable and accessible activity for all ages, and a great excuse to get our children away from video and computer games and into the great outdoors! Approximately 700,000 adults and thousands of young people fish each year in Maryland, with an estimated annual impact of $1 billion on our economy. Gov. Martin O’Malley and Sec. John R. Griffin More than a third of our anglers visit from out of state, testimony to the value and quality of our great fishing resources. We are very fortunate to have expert biologists and managers – working to- gether with our Sport Fisheries, Tidal Fisheries and Oyster Advisory Commissions, and our Coastal Fisheries Advisory Committee, to guide fisheries management across our State. We are also very fortunate to have you -- committed conserva- tionists and advocates – working with us. Your license revenues support protection and enhancement of Maryland’s fishery resources, research and management activities, expanded public access and enhanced law enforcement. And we look forward to strengthening our partnership with you as we work toward our goals for a restored Chesapeake Bay, thriving freshwater streams, and healthy abundant fish populations. Thank you for being a part of a great cultural tradition, and here’s wishing you a terrific year of fishing in Maryland. Martin O’Malley John R. Griffin Governor Secretary About the Cover: This edition of the Maryland Fishing Guide is dedicated to Frances McFaden, who retired from public service after 43 years as a steadfast, ever-helpful, and resourceful Maryland state worker. -

New Insights: Case Study Locations Executive Summary Expanding Population, Increased Fertilizer Use, and More 5 Livestock May Counteract Water Quality Improvements

A tool for watershed management Adjusting our course New Insights summarizes the changes in water quality resulting from The examination of water quality monitoring data associated with best New nutrient reducing practices in more than 40 Chesapeake Bay watershed case management practice implementation in the Chesapeake Bay watershed studies. In many examples, water quality monitoring data reveal the benefits reveals multiple implications for continued efforts in Bay restoration: of restoration practices aimed at reducing nutrient and sediment pollution Investments in sewage treatment plants provide rapid water flowing into our local waters. Insights: quality improvements. 1 The science-based evidence summarized here shows that: National requirements of the Clean Air Act are benefitting the Science-based evidence of • Several groups of pollution-reducing practices, also known as best management 2 Chesapeake Bay watershed. practices or BMPS, are effective at improving water quality and habitats; water quality improvements, Some agricultural practices are providing local benefits • Specific challenges can still impede water quality improvements; and challenges, and opportunities 3 to streams. • More practices that focus on the impacts of intensified agriculture and urban and in the Chesapeake suburban development are needed for healthier waters. Lag times that delay improvements mean patience and persistence 4 are needed to realize the results of our efforts. New Insights: Case study locations Executive Summary Expanding population, increased fertilizer use, and more 5 livestock may counteract water quality improvements. NEW YORK Science should be better used to guide restoration choices and 6 subsequent monitoring is needed to evaluate effectiveness. Proven and innovative stormwater management practices need Sinnemahoning Creek to be implemented and evaluated to maintain and improve Bay 7 health as urban and suburban development expands.