Discovering Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paul Rand: a Significant Collection

paul rand: a significant collection modernism 101 rare design books 1938 ● 1996 “[Rand] has no patience with slickness, with facility; he is a se- vere critic of the hackneyed and the insincere. All this is dead wood to be cleared away.” — E. McKnight Kauffer [Introduction to THOUGHTS ON DESIGN] Paul Rand [1914 – 1996] had established himself as the most influ- ential graphic designer of his time by the ripe old age of 23. Our cata - log cover portrait first appeared in the PM Shorts column from the February – March 1938 PM over the cutline “[Paul Rand] recently appointed art director of Esquire’s New York Office. Rand, who is 23, is one of the country’s youngest art directors.” The lowercase job title presentation underscored the nascent form of the industry that Rand would come to personify over the next half century. The development of Graphic Design as an industry and a profession is the focus of this catalog. Assembled here is a collection of rare books, periodicals and artifacts meant to recount history via a chronological exploration of Rand’s professional roles: first as a media promoter, then advertising designer, then corporate identification specialist and finally as educator. Everybody whose resumé includes the title Art Director in capital let- ters owes a professional debt to Brooklyn native Peretz Rosenbaum and his lifelong quest to clear away the dead wood that threatened to overgrow America and the rest of the postwar world. Catalog Fun Fact Titles appearing in red contain an imbedded URL hotlink to our website modernism101.com. When clicking on a title of interest, your web browser may display this message: If you trust the site, choose Allow. -

Paul Rand Louis Danziger: Early Life and Education

Indisputably, Rand’s most widely known His career began with humble assignments, starting contribution to graphic design are his with a part-time position creating stock images for a corporate identities, many of which are syndicate that supplied graphics to various newspa- still in use. IBM, ABC, Cummins Engine, pers and magazines. Between his class assignments Westinghouse, and UPS, among many and his work, Rand was able to amass a fairly large others, owe their graphical heritage to portfolio, largely influenced by the German advertis- him, though UPS recently carried out a ing style Sachplakat (ornamental poster) as well as controversial update to the classic Rand the works of Gustav Jensen. design. One of his primary strengths, as Maholy-Nagy pointed out, was his abil- ity as a salesman to explain the needs his identities would address for the cor- poration. According to graphic designer Paul rand Louis Danziger: Early life and education Paul Rand (born Peretz Rosenbaum, “ We went from being commer- It was at around this time that he decided to cam- August 15, 1914 – November 26, 1996) cial artists to being graphic de- ouflage (and abbreviate) the overtly Jewish identi- was a well-known American graphic signers largely on his ty telegraphed by ‘Peretz Rosenbaum,’ shortening designer, best known for his corporate merits.” his forename to ‘Paul’ and taking ‘Rand’ from an logo designs. Rand was educated at the uncle to form his new surname. Morris Wyszogrod, Pratt Institute (1929-1932), the Parsons a friend and associate of Rand, noted that “he fig- School of Design (1932-1933), and the ured that ‘Paul Rand,’ four letters here, four letters Art Students League (1933-1934). -

A DESIGNER's ART by Paul Rand. Illustrated. 239 Pp. New Haven

9/19/2018 IN THE BEGINNING WAS THE LOGO - The New York Times ARCHIVES | 1985 By ALAN FERN PAUL RAND: A DESIGNER'S ART By Paul Rand. Illustrated. 239 pp. New Haven. Yale University Press. $39.95. IN our built environment and our civilization of manufactured objects, every product, every printed page, every urban corner has been designed, sometimes badly, sometimes well. Yet we have few opportunities to reflect on the ways designers work and to celebrate their accomplishments. Our painters, sculptors and architects are household names, but few people, apart from the members of the design community, are aware of the identities and the qualities of the principal shapers of the forms with which we are surrounded. Fewer still have an understanding of the thought processes or the intellectual preoccupations of the major designers of our time. The curse of the designer is that he remains anonymous to those who use (and may even admire) his work. Many who read this review will recognize the characteristic logotype of the I.B.M. Corporation, with its blocky letters rendered in horizontal lines of blue or gray; the underlined ''W'' that appears on every Westinghouse product; or the refined, multicolored stenciled letter forms of the El Producto cigar box. But the name of the designer who created them is know primarily to his colleagues. ''Paul Rand: A Designer's Art'' admirably serves to introduce us to the mind and the work of the orginator of these and many other memorable graphic images, and to a man who is one of the most influential and fascinating designers of our time. -

Paul-Rand.Com __ Logos, Flags, and Escutcheons

About Paul Rand Thoughts on Design Gallery Resources Shop News Search Submit Thoughts on Design Logos, Flags, and Escutcheons More Articles by Paul Rand Integrity and Invention Graphis Annual, 1971 t reminds me of the Georgia chain gang,” quipped the IBM executive, when he first eyed the “I striped logo. When the Westinghouse insignia (1960) was first seen, it was greeted similarly with such gibes as “this looks like a pawnbroker’s sign.” How many exemplary works have gone A Selection of Quotes down the drain, because of such pedestrian fault-finding? Bad design is frequently the consequence Various resources of mindless dabbling, and the difficulty is not confined merely to the design of logos. This lack of understanding pervades all visual design. Interview with a Portfolio Center Student There is no accounting for people’s perceptions. Some see a logo, or anything else seeable, the way A witty interview conducted they see a Rorschach inkblot. Others look without seeing either the meaning or even the function of via fax. a logo. It is perhaps, this sort of problem that prompted ABC TV to toy with the idea of “updating” their logo (1962). They realized the folly only after a market survey revealed high audience recognition. This is to say nothing of the intrinsic value of a well-established symbol. When a logo is The Politics of Design designed is irrelevant; quality, not vintage nor vanity, is the determining factor. Originally published in “A Designer’s Art”. There are as many reasons for designing a new logo, or updating an old one, as there are opinions. -

The New York School the NEW YORK SCHOOL

ANM102 | HISTORY OF GRAPHIC AND WEB DESIGN CHAPTER 19 The New York School THE NEW YORK SCHOOL • European designers, escaping the political climate, immigrated to the United States and became major influences in the American design movement. • European design was fairly theoretical and structured, where American design was pragmatic, intuitive and less formal in its approach to organizing space. • New York was the center of the movement in the 1940s. • Emphasis was placed on the expression of ideas and an open, direct presentation of information. William Pickering, title page for the Book of Common Prayer, 1844. CHAPTER 19: THE NEW YORK SCHOOL 2 LOGO DESIGN Paul Rand • Began his career as a promotional and editorial designer for Apparel Arts, Esquire, Ken, Coronet, and Glass Packer. • Collaborated with copywriter Bill Bernbach becoming the prototype for art/copy teams working together. • Created many of the most recognizable logos seen today. William Pickering, title page for the Book of Common Prayer, 1844. CHAPTER 19: THE NEW YORK SCHOOL 3 POSTER DESIGN Paul Rand • style often reflected entertaining puns and wordplay • played with contrasts: red against green, organic against geometric, cut or torn edges against sharp forms, and textural pattern against white • http://www.paul-rand.com/site/posters/ William Pickering, title page for the Book of Common Prayer, 1844. CHAPTER 19: THE NEW YORK SCHOOL 4 PUBLICATION Paul Rand • Created this cover for Direction magazine, 1940 • red dots are symbolically are interpreted as holiday decorations or blood drops William Pickering, title page for the Book of Common Prayer, 1844. CHAPTER 19: THE NEW YORK SCHOOL 5 PUBLICATION Alvin Lustig • graphic designer, architect, and interior designer • became the visual design research director at Look Magazine • heavily involved with design education and in 1951 helped develop a graduate graphic design program at Yale University William Pickering, title page for the Book of Common Prayer, 1844. -

The Rise of Research in Graphic Design

Introduction: The Rise of Research in Graphic Design AUDREY BENNETT Graphic design is at a crossroads. Looking back, one sees designers engaged in a process where intuition informs the development of visual rhetoric intended to evoke a response from a target audience. Looking ahead, one sees them engaged in a process where research is integrated into the design of objects and experiences for and with the audience. By adopting interdisciplinary research approaches, graphic designers can both question and agrm their intuitive inclinations, and place this process in conversation with peers and even the lay public. Traditionally graphic design theory has privileged intuition and creativity over empirical research. This book seeks to provide an alternative approach to graphic design theory by surveying the best work, past to present, on research- based graphic design theory. The question then is: what are graphic design’s theories? It can be argued that the art-based principles of graphic design—including (but not limited to) contrast, hierarchy, repetition, alignment, and color—are in fact theories proven through a long history of successful experimentation in practice.1 Indeed, graphic designers—through professional practice— have tested and retested to the point where it makes sense to refer to these theories as laws or principles. Marty Neumeier’s and James Souttar’s analyses of the work of John Rushworth, Massimo Vignelli, 16 Nancy Skolos, and Chuck Close, confirm the replicability of these principles to create aesthetics that sell ideas, products, and experiences.2 Yet within the discipline of graphic design these principles are not regarded as “proven” theories because graphic design historically lacks a strong research agenda. -

AMERICAN MODERNISM / Overview 1 / 50

GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / AMERICAN MODERNISM / OVerVieW 1 / 50 American Modernism 1 European Imports 6 2 Native Modernists 24 3 Paul Rand 40 © Kevin Woodland, 2019 Iwao Yamawaki, The Attack of the Bauhaus, 1932. GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / AMERICAN MODERNISM / OVerVieW 2 / 50 © Kevin Woodland, 2019 Dessau Bauhaus, circa 1933 GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / AMERICAN MODERNISM / OVerVieW 3 / 50 © Kevin Woodland, 2019 Dessau Bauhaus, circa 1933 GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / AMERICAN MODERNISM / OVerVieW 4 / 50 © Kevin Woodland, 2019 Hitler’s Bunker, 50 feet under Berlin, 1945 GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / AMERICAN MODERNISM / OVerVieW 5 / 50 © Kevin Woodland, 2019 Dessau Bauhaus, 1945 GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / AMERICAN MODERNISM 6 / 50 1930’S European Imports An influx of European ideas made its way into America through several avenues during the 1930’s. © Kevin Woodland, 2019 Walker Evans, Houses and Billboards, Atlanta, 1936 GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / AMERICAN MODERNISM / The BAUhaUS 7 / 50 © Kevin Woodland, 2019 Walker Evans, circa 1930’s GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / AMERICAN MODERNISM / The BAUhaUS 8 / 50 1920’S–30’S Modernism in America gained a foothold in the form of: • Book design • Editorial design • Corporate identity New typeface designs, including Futura and Kabel, became available in America, spurring the modern movement forward. – MEGGS © Kevin Woodland, 2019 Paul Renner, Futura type specimen, 1927 GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / AMERICAN MODERNISM / The BAUhaUS 9 / 50 1897–1967 George Salter • Bremman, Germany • Emmigrated to U.S. in 1934 • Book Cover designer • Magazine Cover designer • American citizen in 1940 Alfred Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz launched his career. -

Research Paul Rand

Research Paul Rand (born Peretz Rosenbaum) – (1914 – 1996) American graphic designer. Well known for designing corporate logos. He helped originate the Swiss Style of graphic design. http://www.paul-rand.com/foundation/biography/#.UukMANDFKLI “Emerging from the modernist and constructivist ideals, the Swiss Style can be defined as an authentic pursue for simplicity – the beauty in the underlines of a purpose, not beauty as a purpose in itself. The principle “form follows function” became a battle-cry of Modernist architects after the 1930s. As a consequence of this principle, most of the Swiss Style craft is devoted to the minimal elements of style such as typography and content layout rather than on textures and illustrations.” http://www.smashingmagazine.com/2009/07/17/lessons-from-swiss-style-graphic- design/ 1981 1972 The left image is cleverly created because each letter is symbolised with a picture. Rand liked to create playful images and this image definitely reflects that. The right image is more suited for a business because the image is plain and simple – it consists of horizontal blue lines. However, there is a lot of hidden meaning to this image because the striped lines looks like venetian blinds, the type of blinds that we usually see on windows of business. It also looks like lines that we would see in an old computer screen, this is a good representation of the company because the company is a computer business. We can see the striped effect on the “m” in the image on the left. If someone hadn’t heard of the company IBM before they might get confused by the symbols shown in the left design. -

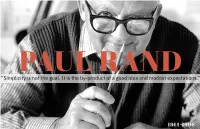

Simplicity Is Not the Goal. It Is the By-Product of a Good Idea and Modest Expectations.”

PAUL RAND “Simplicity is not the goal. It is the by-product of a good idea and modest expectations.” 1914-1996 Biography/Background Work Experience 1937-1941 - Art director for Esquire and Apparel Arts magazine Peretz Rosenbaum was born on August 15th, 1914 in Brooklyn, New York. ---He believed that lines, shapes and colors could become He later changed his name to Paul Rand, which sounded more American. He message-conveying signs and symbols in visual communications and artis- wanted to do away with his Jewish identity because he thought he would be tic composition more successful. 1941 – 1954 – art director of the William H. Weintraub advertising agency, From a very young age, he had a profound interest in designing (particularly collaborated with Bill Bernbach painting at first), which ultimately influenced his future career in design. ---Paul thought that text and images were integrated into a whole, with words and pictures working together to create an effective Paul Rand created trademarks up to the day he died. He passed away on message November 26, 1996 at the age of 82. 1947 - Rand published his first book,Thoughts on Design. ---This book would remain influential for decades, making the case for the essential relationship between how something looked and what it accom- Awards plished. Education 1972 - Rand was inducted in the New York Art Directors 1950s and 1960s – American corporations were turning to graphic Club Hall of Fame. This is a professional organization in the design and creative industries. The Art Directors Club His father said that art alone wouldn’t be sufficient enough for his son, so he was enrolled in designers to create trademarks. -

Why Paul Rand Hates Logos’, Blueprint, September 1989

‘Why Paul Rand hates logos’, Blueprint, September 1989 In the pantheon of US designers, they don’t come more eminent than Paul Rand. He made corporate identity into modernist clarity ‘The IBM corporate identity manual took many years. It was boring. You have to be Swiss to do that kind of stuff – I don’t have the patience or the ability. Elliot Noyes? That guy was a good politician with Tom Watson. He got me in to do a presentation in 1956, but that was all. Elliot, he had nothing to do with the work I did. Arthur Pulos and Stephen Bayley say he did, but that’s for the birds. Elliot used Charles Eames and me to critique his finished models, though. But I never asked him to critique my work. Never’. Getting to interview Paul Rand is a succession of surprises. It’s he who answers the phone, in a Brooklyn Jewish accent thicker than chicken soup. He has no secretary; no computer, just a fax. Then, he turns out to be accessible at short notice, even though, at the age of 75, he’s snowed under with work: for IBM (still); for the Department of the Interior (commemorating the 20Oth anniversary of Benjamin Franklin’s death for the City of Philadelphia); and for Harvard (to mark the completion of a new building). Rand is prepared to talk, he says disarmingly, because that will get him out of having to attend to his clients. Did he have much of a formal training? No. The scatological Brooklyn expletives run even faster than usual when Rand describes his brief sojourns at Pratt and Parsons: ‘We were led into a barn and tied. -

Paul-Rand.Com __ Biography

About Paul Rand Thoughts on Design Gallery Resources Shop News Search Submit Paul Rand: A Brief Biography PAUL RAND (BORN PERETZ ROSENBAUM, AUGUST 15, 1914 – NOVEMBER 26, 1996) was a well-known American graphic designer, best known for his corporate logo designs. Rand was educated at the Pratt Institute (1929-1932), the Parsons School of Design (1932-1933), and the Art Students League (1933-1934). He was one of the originators of the Swiss Style of graphic design. From 1956 to 1969, and beginning again in 1974, Rand taught design at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. Rand was inducted into the New York Art Directors Club Hall of Fame in 1972. He designed many posters and corporate identities, including the logos for IBM, UPS and ABC. Rand died of cancer in 1996. Early life and education Peretz Rosenbaum was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1914. As Orthodox Jewish law forbids the creation of graven images that can be worshiped as idols, Rand’s career creating icons venerated in the temple of global capitalism seemed as unlikely as any. It was one that he embraced at a very young age, painting signs for his father’s grocery store as well as for school events at P.S. 109. Rand’s father did not believe art could provide his son with a sufficient livelihood, and so he required Paul to attend Manhattan’s Harren High School while taking night classes at the Pratt Institute, though “neither of these schools offered Rand much stimulation.” Despite studying at Pratt and other institutions in the New York area (including Parsons School of Design and the Art Students League), Rand was by-and-large “self-taught as a designer, learning about the works of Cassandre and Moholy-Nagy from European magazines such as [Gebrauchsgraphik].” Early career His career began with humble assignments, starting with a part-time position creating stock images for a syndicate that supplied graphics to various newspapers and magazines. -

Mr. Keedy It Lives! This Is a Very Scary Essay

Zombie Modernism Mr. Keedy it Lives! This is a very scary essay. It’s about death and denial. But you don’t have to be afraid to read it, because it’s just language, and meaning is arbitrary. At least that is what those nasty postmodernists, and deconstructivists, want you to believe. But we know better. There is a right way and a wrong way to do everything. A good way and a bad way, a rational way and a crazy way, a clear way and a chaotic way, the modern way and the modern way. In graphic design, there is no alternative to modernism. To predate modernism, is to be a commercial artist, printer or scribe, not a designer, because the designer was born out of modernism. To postdate modernism is equally incomprehensible for most designers, because it exists outside their realm of comprehension. In most areas of cultural production like art, architecture, music, and literature, modernism was just one more event in a continuing life cycle. Graphic design, on the other hand, did not have sufficient time to develop a mature sense of self—the umbilical cord had not been severed yet. So when modernism died, many designers’ ideology died with it. However, they did not go peacefully into that dark night. They refused to acknowledge their own ideological demise, and they continue to haunt the living, moaning and groaning because they no longer belong to this world. That is the fate of the Zombie Modernist, the living dead who design among us. In the beginning, when modernism was young, it was a radical idea that positioned itself in opposition to a more conservative traditionalism.