Seasonal Ranges of Dall's Sheep, Mackenzie Mountains, Northwest Territories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

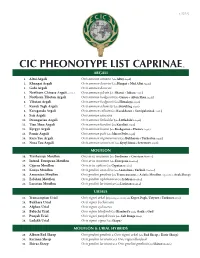

Cic Pheonotype List Caprinae©

v. 5.25.12 CIC PHEONOTYPE LIST CAPRINAE © ARGALI 1. Altai Argali Ovis ammon ammon (aka Altay Argali) 2. Khangai Argali Ovis ammon darwini (aka Hangai & Mid Altai Argali) 3. Gobi Argali Ovis ammon darwini 4. Northern Chinese Argali - extinct Ovis ammon jubata (aka Shansi & Jubata Argali) 5. Northern Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Gansu & Altun Shan Argali) 6. Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Himalaya Argali) 7. Kuruk Tagh Argali Ovis ammon adametzi (aka Kuruktag Argali) 8. Karaganda Argali Ovis ammon collium (aka Kazakhstan & Semipalatinsk Argali) 9. Sair Argali Ovis ammon sairensis 10. Dzungarian Argali Ovis ammon littledalei (aka Littledale’s Argali) 11. Tian Shan Argali Ovis ammon karelini (aka Karelini Argali) 12. Kyrgyz Argali Ovis ammon humei (aka Kashgarian & Hume’s Argali) 13. Pamir Argali Ovis ammon polii (aka Marco Polo Argali) 14. Kara Tau Argali Ovis ammon nigrimontana (aka Bukharan & Turkestan Argali) 15. Nura Tau Argali Ovis ammon severtzovi (aka Kyzyl Kum & Severtzov Argali) MOUFLON 16. Tyrrhenian Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka Sardinian & Corsican Mouflon) 17. Introd. European Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka European Mouflon) 18. Cyprus Mouflon Ovis aries ophion (aka Cyprian Mouflon) 19. Konya Mouflon Ovis gmelini anatolica (aka Anatolian & Turkish Mouflon) 20. Armenian Mouflon Ovis gmelini gmelinii (aka Transcaucasus or Asiatic Mouflon, regionally as Arak Sheep) 21. Esfahan Mouflon Ovis gmelini isphahanica (aka Isfahan Mouflon) 22. Larestan Mouflon Ovis gmelini laristanica (aka Laristan Mouflon) URIALS 23. Transcaspian Urial Ovis vignei arkal (Depending on locality aka Kopet Dagh, Ustyurt & Turkmen Urial) 24. Bukhara Urial Ovis vignei bocharensis 25. Afghan Urial Ovis vignei cycloceros 26. -

August 8, 2013

August 8, 2013 The Sahtu Land Use Plan and supporting documents can be downloaded at: www.sahtulanduseplan.org Sahtu Land Use Planning Board PO Box 235 Fort Good Hope, NT X0E 0H0 Phone: 867-598-2055 Fax: 867-598-2545 Email: [email protected] Website: www.sahtulanduseplan.org i Cover Art: “The New Landscape” by Bern Will Brown From the Sahtu Land Use Planning Board April 29, 2013 The Sahtu Land Use Planning Board is pleased to present the final Sahtu Land Use Plan. This document represents the culmination of 15 years of land use planning with the purpose of protecting and promoting the existing and future well-being of the residents and communities of the Sahtu Settlement Area, having regard for the interests of all Canadians. From its beginnings in 1998, the Board’s early years focused on research, mapping, and public consultations to develop the goals and vision that are the foundation of the plan. From this a succession of 3 Draft Plans were written. Each Plan was submitted to a rigorous review process and refined through public meetings and written comments. This open and inclusive process was based on a balanced approach that considered how land use impacts the economic, cultural, social, and environmental values of the Sahtu Settlement Area. The current board would like to acknowledge the contributions of former board members and staff that helped us arrive at this significant milestone. Also, we would like to extend our gratitude to the numerous individuals and organizations who offered their time, energy, ideas, opinions, and suggestions that shaped the final Sahtu Land Use Plan. -

The Status of Mountain Goats in Canada's Northwest Territories

The Status Of Mountain Goats In Canada’s Northwest Territories ALASDAIR VEITCH, Department of Resources, Wildlife & Economic Development, Government of the Northwest Territories, P.O. Box 130, Norman Wells, NT, Canada X0E 0V0 ELLEN SIMMONS, ET Enterprises, Site 9B, Comp. 20, RR1, Kaleden, BC, Canada V0H 1K0 MIKI PROMISLOW, Sahtu Geographic Information System Project, P.O. Box 130, Norman Wells, NT, Canada X0E 0V0 DOUGLAS TATE, Nahanni National Park Reserve, P. O. Box 348, Fort Simpson, NT, Canada X0E 0N0 MICHELLE SWALLOW, Department of Resources, Wildlife & Economic Development, P.O. Box 130, Norman Wells, NT, Canada X0E 0V0 RICHARD POPKO, Department of Resources, Wildlife & Economic Development, P.O. Box 130, Norman Wells, NT, Canada X0E 0V0 Abstract: Mountain goats (Oreamnos americanus) are the least studied ungulate species that occurs in the Northwest Territories. The distribution of goats in the territory – both historically and at present - is limited to the lower half of the 130,000 km2 Mackenzie Mountains between the Yukon-NWT border and the east edge of the range, including a portion of Nahanni National Park Reserve. Due to the limited annual harvest of goats and the extremely high cost for doing research in this remote region - few surveys to estimate size of mountain goat populations have occurred in the Mackenzie Mountains. Biologists working with federal and territorial wildlife agencies, Parks Canada, and private environmental consulting companies have sporadically collected limited information about mountain goats during the course of studies on other species in the Mackenzies since 1966. In 2001, we interviewed each of the 8 outfitters licenced to provide services to non-resident hunters in the Mackenzie Mountains to document their knowledge about mountain goat distribution and estimated numbers in their zones. -

Nahanni National Park - 2017 Conservation Outlook Assessment (Archived)

IUCN World Heritage Outlook: https://worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org/ Nahanni National Park - 2017 Conservation Outlook Assessment (archived) IUCN Conservation Outlook Assessment 2017 (archived) Finalised on 09 November 2017 Please note: this is an archived Conservation Outlook Assessment for Nahanni National Park. To access the most up-to-date Conservation Outlook Assessment for this site, please visit https://www.worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org. Nahanni National Park عقوملا تامولعم Country: Canada Inscribed in: 1978 Criteria: (vii) (viii) Located along the South Nahanni River, one of the most spectacular wild rivers in North America, this park contains deep canyons and huge waterfalls, as well as a unique limestone cave system. The park is also home to animals of the boreal forest, such as wolves, grizzly bears and caribou. Dall's sheep and mountain goats are found in the park's alpine environment. © UNESCO صخلملا 2017 Conservation Outlook Good with some concerns The geological features of the site and its outstanding scenic beauty have been well preserved and remain in a good condition. There are natural threats from increased permafrost thaw/ landsliding and possible increase in storm event flooding. Hazards from the established mining activities are increasing. However, the potential hazards from full-scale mining at the Prairie Creek site are substantial but, at time of this assessment, it does not appear likely that that will occur in the near future. From an ecological integrity point of view the massive expansion of the national park and the creation of a new Naats’ihch’oh National Park Reserve adjacent to it have improved the long term outlook of the original World Heritage site which remains within its 1978 boundaries. -

Keele River Flat Sheet

KEELE RIVER Exploring Canada’s Arctic by Canoe The Northwest Territories has never been tamed. ACCESS POINT Larger than all but a handful of sovereign na- NORMAN WELLS, NWT tions, it’s where Canada’s most remote rivers weave through an empire of peaks. It’s where caribou, mountain sheep, moose and grizzlies travel freely in pristine wilderness. And where NORMAN WELLS people trace timeless paths, following lifeways KEELE RIVER richer than the modern world can know. YELLOWKNIFE Your Northern Adventure Experts Join us for a true wilderness adventure in a EDMONTON VANCOUVER limitless land. We offer trips that suit all tastes CALGARY and abilities, from relaxed to high octane. From the rugged Barrenlands to the Mack- enzie Mountains, or watery depths of Great OTTAWA TORONTO Slave Lake, we have an adventure for you. Our well-organized expeditions are backed by an exceptional safety record. As the largest Northern-owned paddling outfitter, we know the North like no one else. [email protected] 1-867-445-4512 www.jackpinEpaddle.com A Wild Northern River Keele River Wilderness Canoe Expedition 13 days – 12 nights, Novice to Intermediate Paddlers The Keele River is one of the most remote and beautiful mountain rivers in the Northwest Territories. It’s headwaters lie deep inside the Macken- zie Mountains and flow eastward for 300km before emptying out into the Mackenzie River. The Keele River is known for its breath-taking hikes, stun- WHAT IS INCLUDED? ning mountain views and some of the most memorable campsites you’ll find Charter flights to and from the anywhere on this planet (wide-open gravel bars sporting dramatic mountain river; airport pick-up in Norman vistas). -

Le of Contents

A COMPILATION OF PAPERS PRESENTED AT THE 23rd ANNUAL MEETING, APRIL 46,1979 AT BOULDER CITY, NEVADA LE OF CONTENTS Page STATUS OF THE ZION DESERT BIGHORN REINTRODUCTION PROJECT-1978 Henry E.McCutchon ............................................................................. 81 TEXAS REINTRODUCTION EFFORTS STATUS REPORT-1979 Jack Kilpatric ................................................................................... 82 BlQHORM SWEEP STATUS REPORT FROM NEW MEXICO AndrewV.Sandoval .............................................................................. 82 LAVA BEDS BIGHORN SHEEP PROGRAM--UPDATE RobertA.Dalton ................................................................................. 88 UTAH BIGHORN SHEEP STATUS REPORT Grant K. Jense, James W. Bates and Jay A. Robertson. ............................................... .89 STATUS OF THE BIG HATCHET DESERT SHEEP POPULATION, NEW MEXICO Tom J. Watts ................................................................................... 92 ARIZONA BIGHORN SHEEP STATUS REPORT-1979 Paul M. Webb ................................................................................... 94 BIGHORN SHEEP POPULATION ESTIMATE FOR THE SOUTH TONTQ PLATEAU-GRAND CANYON Jim Walters .................................................................................... 96 BIGHORN SHEEP STATUS REPORT-NEVADA George K.Tsukamoto ........................................................................... 107 DESERT BIGHORN COUNCIL 1970-1980 ................................................................ -

Your Big River Journey – Credit Information

Your Big River Journey – Credit Information Fort Smith Header image, aerial photo of Fort Smith; photograph by GNWT. Fort Smith Hudson's Bay Company Ox Carts, CREDIT: NWT Archives/C. W. Mathers fonds/N-1979-058: 0013 Portage with 50 ft scow, CREDIT: NWT Archives/C. W. Mathers fonds/N-1979-058: 0015 Fifty-foot scow shooting a rapid, CREDIT: NWT Archives/C. W. Mathers fonds/N- 1979-058: 0019 Henry Beaver smudging with grandson, Fort Smith; photograph by Tessa Macintosh. Symone Berube pays the water, Fort Smith, video by Michelle Swallow. Mary Shaefer shows respect to the land, Fort Smith, video by ENR. Paddle stamp; illustration by Sadetło Scott. Grand Detour Header image, Grand Detour; photograph by Michelle Swallow. Image of Grand Detour portage, CREDIT: NWT Archives/John (Jack) Russell fonds/N-1979-073: 0100 Image of dogs hauling load up a steep bank near Grand Detour, CREDIT: NWT Archives/John (Jack) Russell fonds/N-1979-073: 0709 Métis sash design proposal; drawing by Lisa Hudson. Lisa Hudson wearing Métis sash; photograph by Lisa Hudson. Métis sash stamp; illustration by Sadetło Scott. Slave River Delta Header image, Slave River Delta, Negal Channel image; photograph by GNWT. How I Respect the Land: Conversations from the South Slave, Rocky Lafferty, Fort Resolution; video by GNWT ENR. Male and female scaup image; photograph by Danica Hogan. Male and female mallards image; photograph by JF Dufour. Slave River Delta bird image; photograph by Gord Beaulieu. Snow geese stamp; illustration by Sadetło Scott. Fort Resolution Header image, aerial photo of Fort Resolution; photograph by GNWT. -

Giant Moose Hunting in Russia - Magada 2022-2023 9-12 Hunting Days (Excluding Travel) Hosted Hunt for a Group of 4-6 People

Giant Moose hunting in Russia - Magada 2022-2023 9-12 hunting days (excluding travel) Hosted hunt for a group of 4-6 people Highlights Siberia- the biggest untouched tundra-reserve on the earth- is the land of the giant moose. This hunting trip takes place in Magadan region, an about 1.2 million square kilometer- province in East Siberia. We hunt along the Omolon river’s hills and valleys, about a 2.5-hour charter flight from Magadan. Most of this vast land is covered by snow and ice all-year round. In the winter, the temperature can drop to minus 50-70 Celsius there. We offer an authentic, adventurous hosted trip for the gigantic-palmed moose. Hunters who want to get a taste of an authentic ‘Wild East’ hunt, could make a trip of lifetime. Our Russian partner takes only 2 small groups to this hunting area every year. Thanks to the limited hunting pressure, last years’ hunting proved to be phenomenal results. Most of our clients had a chance to harvest even a second animal additional to their contracted package. A multilingual staff from our agency will assist the group along the trip from the arrival in Magadan. Additional to moose, there are 4 other big game species available to hunt. Besides hunting, fishing is also allowed on the river. Travel: Hunters arrive in the region’s capital city, Magadan, usually via a connecting flight in Moscow. Our representative is waiting for the guests at the airport and help them check in the country through the VIP entry. -

Adopted: April 29, 2013 Approved: August 8, 2013

Land) Designation Conservation Zone CRs & CRs# 1-14 Prohibitions Prohibition: Bulk water removal; Mining E&D; Oil and Gas E&D; Power Development; Forestry; Quarrying Map # 10 Area 8,982 km2 Land Sahtu Subsurface Ownership Sahtu Surface Ownership Ownership - 14.7% Location & Shúhtagot'ine Néné lies within the Mackenzie Mountains. It has two sections. One Boundaries includes the northern portion of the Canol Trail and Dodo Canyon. The other encompasses parts of the Keele River (Begáádeé), Redstone and Ravens Throat Rivers (Tátsõk’áádeé), Drum Lake, June Lake and Caribou Flats. Reason for Establishment Shúhtagot'ine Néné, or Mountain Dene Land is ecologically and culturally important to the Dene and Metis from Norman Wells and Tulita. The Mountain Dene used traditional trails travelling mostly up the Keele River in the summer to hunt moose, make moose skin boats and to return from the mountains in the fall.241 Important wildlife habitats support a number of species as well as hunting, trapping and fishing in the rivers valleys and mountains. Values to be Protected: Archaeological and burial sites, cultural and heritage sites. Values to be Respected: Shúhtagot'ine Néné supports several COSEWIC and SARA “at risk” listed species242 which either inhabit the area all-year round or as migrants. Some of those species are: boreal woodland caribou, northern mountain caribou, wolverine, peregrine falcon and rusty blackbird. The harlequin duck, bull trout and inconnu fish are ranked by ENR as may-be-at-risk under the general status program.243 The zone has amongst some of the highest density of grizzly bears in the NWT. -

A Freshwater Classification of the Mackenzie River Basin

A Freshwater Classification of the Mackenzie River Basin Mike Palmer, Jonathan Higgins and Evelyn Gah Abstract The NWT Protected Areas Strategy (NWT-PAS) aims to protect special natural and cultural areas and core representative areas within each ecoregion of the NWT to help protect the NWT’s biodiversity and cultural landscapes. To date the NWT-PAS has focused its efforts primarily on terrestrial biodiversity, and has identified areas, which capture only limited aspects of freshwater biodiversity and the ecological processes necessary to sustain it. However, freshwater is a critical ecological component and physical force in the NWT. To evaluate to what extent freshwater biodiversity is represented within protected areas, the NWT-PAS Science Team completed a spatially comprehensive freshwater classification to represent broad ecological and environmental patterns. In conservation science, the underlying idea of using ecosystems, often referred to as the coarse-filter, is that by protecting the environmental features and patterns that are representative of a region, most species and natural communities, and the ecological processes that support them, will also be protected. In areas such as the NWT where species data are sparse, the coarse-filter approach is the primary tool for representing biodiversity in regional conservation planning. The classification includes the Mackenzie River Basin and several watersheds in the adjacent Queen Elizabeth drainage basin so as to cover the ecoregions identified in the NWT-PAS Mackenzie Valley Five-Year Action Plan (NWT PAS Secretariat 2003). The approach taken is a simplified version of the hierarchical classification methods outlined by Higgins and others (2005) by using abiotic attributes to characterize the dominant regional environmental patterns that influence freshwater ecosystem characteristics, and their ecological patterns and processes. -

Brochure Highlight Those Impressive Russia

2019 44 years and counting The products and services listed Join us on Facebook, follow us on Instagram or visit our web site to become one Table of Contents in advertisements are offered and of our growing number of friends who receive regular email updates on conditions Alaska . 4 provided solely by the advertiser. and special big game hunt bargains. Australia . 38 www.facebook.com/NealAndBrownleeLLC Neal and Brownlee, L.L.C. offers Austria . 35 Instagram: @NealAndBrownleeLLC no guarantees, warranties or Azerbaijan . 31 recommendations for the services or Benin . 18 products offered. If you have questions Cameroon . 19 related to these services, please contact Canada . 6 the advertiser. Congo . 20 All prices, terms and conditions Continental U .S . 12 are, to the best of our knowledge at the Ethiopia . 20 time of printing, the most recent and Fishing Alaska . 42 accurate. Prices, terms and conditions Fishing British Columbia . 41 are subject to change without notice Fishing New Zealand . 42 due to circumstances beyond our Kyrgyzstan . 31 control. Jeff C. Neal Greg Brownlee Trey Sperring Mexico . 14 Adventure travel and big game 2018 was another fantastic year for our company thanks to the outfitters we epresentr and the Mongolia . 32 hunting contain inherent risks and clients who trusted us. We saw more clients traveling last season than in any season in the past, Mozambique . 21 dangers by their very nature that with outstanding results across the globe. African hunting remained strong, with our primary Namibia . 22 are beyond the control of Neal and areas producing outstanding success across several countries. Asian hunting has continued to be Nepal . -

List of 28 Orders, 129 Families, 598 Genera and 1121 Species in Mammal Images Library 31 December 2013

What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library LIST OF 28 ORDERS, 129 FAMILIES, 598 GENERA AND 1121 SPECIES IN MAMMAL IMAGES LIBRARY 31 DECEMBER 2013 AFROSORICIDA (5 genera, 5 species) – golden moles and tenrecs CHRYSOCHLORIDAE - golden moles Chrysospalax villosus - Rough-haired Golden Mole TENRECIDAE - tenrecs 1. Echinops telfairi - Lesser Hedgehog Tenrec 2. Hemicentetes semispinosus – Lowland Streaked Tenrec 3. Microgale dobsoni - Dobson’s Shrew Tenrec 4. Tenrec ecaudatus – Tailless Tenrec ARTIODACTYLA (83 genera, 142 species) – paraxonic (mostly even-toed) ungulates ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BOVIDAE (46 genera) - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Addax nasomaculatus - Addax 2. Aepyceros melampus - Impala 3. Alcelaphus buselaphus - Hartebeest 4. Alcelaphus caama – Red Hartebeest 5. Ammotragus lervia - Barbary Sheep 6. Antidorcas marsupialis - Springbok 7. Antilope cervicapra – Blackbuck 8. Beatragus hunter – Hunter’s Hartebeest 9. Bison bison - American Bison 10. Bison bonasus - European Bison 11. Bos frontalis - Gaur 12. Bos javanicus - Banteng 13. Bos taurus -Auroch 14. Boselaphus tragocamelus - Nilgai 15. Bubalus bubalis - Water Buffalo 16. Bubalus depressicornis - Anoa 17. Bubalus quarlesi - Mountain Anoa 18. Budorcas taxicolor - Takin 19. Capra caucasica - Tur 20. Capra falconeri - Markhor 21. Capra hircus - Goat 22. Capra nubiana – Nubian Ibex 23. Capra pyrenaica – Spanish Ibex 24. Capricornis crispus – Japanese Serow 25. Cephalophus jentinki - Jentink's Duiker 26. Cephalophus natalensis – Red Duiker 1 What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library 27. Cephalophus niger – Black Duiker 28. Cephalophus rufilatus – Red-flanked Duiker 29. Cephalophus silvicultor - Yellow-backed Duiker 30. Cephalophus zebra - Zebra Duiker 31. Connochaetes gnou - Black Wildebeest 32. Connochaetes taurinus - Blue Wildebeest 33. Damaliscus korrigum – Topi 34.