Le of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prehistoric Trackways National Monument Recreation Area Management Plan

October 2020 Prehistoric Trackways National Monument Recreation Area Management Plan Environmental Assessment DOI-BLM-NM-L0000-2021-0004-EA Las Cruces District Office 1800 Marquess Street Las Cruces, New Mexico 88005 575-525-4300 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 1 1.1. Purpose and Need ........................................................................................................... 1 1.2. Decision to Be Made ....................................................................................................... 1 1.3. RAMP Planning Process ................................................................................................ 3 1.4. Plan Conformance and Relationship to Statutes and Regulations ............................ 3 1.4.1. Plan Conformance ..................................................................................................... 3 1.4.2. Relationship to Statutes and Regulations .................................................................. 5 1.5. Scoping and Issues .......................................................................................................... 6 1.5.1. Internal Scoping ........................................................................................................ 6 1.5.2. Internal and External Scoping ................................................................................... 7 1.5.3. Issues ........................................................................................................................ -

Field Guide to the Sandia Mountains, Edited by Robert Julyan & Mary

Volume 45 Issue 4 Fall 2005 Fall 2005 Field Guide to the Sandia Mountains, edited by Robert Julyan & Mary Stuever Nancy Harbert Recommended Citation Nancy Harbert, Field Guide to the Sandia Mountains, edited by Robert Julyan & Mary Stuever, 45 Nat. Resources J. 1120 (2005). Available at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nrj/vol45/iss4/11 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Natural Resources Journal by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. 1120 NATURAL RESOURCES JOURNAL [Vol. 45 Field Guide to the Sandia Mountains. Edited by Robert Julyan & Mary Stuever: Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2005. Pp. 255. $19.95 spiral-bound paperback. This easy-to-absorb handbook does not pretend to be an exhaustive manual to the Sandia Mountains. Early on, editor Robert Julyan, who is best known for his book The Place Names of New Mexico, makes it clear that the intention among the guide's many contributors is to provide an introduction to the various elements that combine to make up the Sandia Mountains, a compact mountain range that provides the eastern backdrop for Albuquerque. With hundreds of plants and animals, not to mention microbes and soil types, Julyan points out that it would be impossible to represent them all in a guidebook. Therefore, the book focuses on the species and features that visitors are most likely to encounter. Because of the range's proximity to Albuquerque, a city of nearly 500,000 people, it is probably trampled on more than any other mountains in the state. -

Precise Age and Biostratigraphic Significance of the Kinney Brick Quarry Lagerstätte, Pennsylvanian of New Mexico, USA

Precise age and biostratigraphic significance of the Kinney Brick Quarry Lagerstätte, Pennsylvanian of New Mexico, USA Spencer G. Lucas1, Bruce D. Allen2, Karl Krainer3, James Barrick4, Daniel Vachard5, Joerg W. Schneider6, William A. DiMichele7 and Arden R. Bashforth8 1New Mexico Museum of Natural History, 1801 Mountain Road N.W., Albuquerque, New Mexico, 87104, USA email: [email protected] 2New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources, 801 Leroy Place, Socorro, New Mexico, 87801, USA email: [email protected] 3Institute of Geology and Paleontology, University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, A-6020, Austria email: [email protected] 4Department of Geosciences, Texas Tech University, Box 41053, Lubbock, Texas, 79409, USA email: [email protected] 5Université des Sciences et Technologies de Lille, UFR des Sciences de la Terre, UPRESA 8014 du CNRS, Laboratoire LP3, Bâtiment SN 5, F-59655 Villeneuve d’Ascq, Cédex, France email: [email protected] 6TU Bergakademie Freiberg, Cottastasse 2, D-09596 Freiberg, Germany email:[email protected] 7Department of Paleobiology, NMNH Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560 email: [email protected] 8Geological Museum, Natural History Museum of Denmark, University of Copenhagen, Øster Voldgade 5-7, 1350 Copenhagen K, Denmark email: [email protected] ABSTRACT: The Kinney Brick Quarry is a world famous Late Pennsylvanian fossil Lagerstätte in central New Mexico, USA. The age assigned to the Kinney Brick Quarry (early-middle Virgilian) has long been based more on its inferred lithostratigraphic position than on biostratigraphic indicators at the quarry. We have developed three datasets —-stratigraphic position, fusulinids and conodonts— that in- dicate the Kinney Brick Quarry is older, of middle Missourian (Kasimovian) age. -

Mule Deer and Antelope Staff Specialist Peregrine Wolff, Wildlife Health Specialist

STATE OF NEVADA Steve Sisolak, Governor DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE Tony Wasley, Director GAME DIVISION Brian F. Wakeling, Chief Mike Cox, Bighorn Sheep and Mountain Goat Staff Specialist Pat Jackson, Predator Management Staff Specialist Cody McKee, Elk Staff Biologist Cody Schroeder, Mule Deer and Antelope Staff Specialist Peregrine Wolff, Wildlife Health Specialist Western Region Southern Region Eastern Region Regional Supervisors Mike Scott Steve Kimble Tom Donham Big Game Biologists Chris Hampson Joe Bennett Travis Allen Carl Lackey Pat Cummings Clint Garrett Kyle Neill Cooper Munson Sarah Hale Ed Partee Kari Huebner Jason Salisbury Matt Jeffress Kody Menghini Tyler Nall Scott Roberts This publication will be made available in an alternative format upon request. Nevada Department of Wildlife receives funding through the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration. Federal Laws prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, sex, or disability. If you believe you’ve been discriminated against in any NDOW program, activity, or facility, please write to the following: Diversity Program Manager or Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Nevada Department of Wildlife 4401 North Fairfax Drive, Mailstop: 7072-43 6980 Sierra Center Parkway, Suite 120 Arlington, VA 22203 Reno, Nevada 8911-2237 Individuals with hearing impairments may contact the Department via telecommunications device at our Headquarters at 775-688-1500 via a text telephone (TTY) telecommunications device by first calling the State of Nevada Relay Operator at 1-800-326-6868. NEVADA DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE 2018-2019 BIG GAME STATUS This program is supported by Federal financial assistance titled “Statewide Game Management” submitted to the U.S. -

J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Be. Vol. 104(2), May-August, 200"

- - 4;. J. Bombay Nat. Hist. be. Vol. 104(2), May-August, 200" POPULATION STATUS OF MONGOLIAN ARGALI OVIS AMMON FERENCE TO SUSTAINABLE USE MANAGEMENT Margaret Michael R. Frisina, Yondon Onon- and R. Frisina Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, 104 (2), May-Aug 2007 140-144 POPULATION STATUS OF MONGOLIAN ARGALI OVIS AMMON WITH REFERENCE TO SUSTAINABLE USE MANAGEMENT1 MICHAELR. FRISINA',YONDON ON0N3 AND R. MARGARETFRISINA~ 'Accepted December 2005 'Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife & Parks, 1330 West Gold Street, Butte, MT 59701. Email: [email protected] "~nstitute of Biology, Mongolian Academy of Sciences, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. Email: [email protected] "Member, Rocky Mountain Outdoor Writers and Photographers, 1330 West Gold Street, Butte, MT 59701. Email: [email protected] Using repeatable protocols, a survey ofArgali sheep (Ovis nnimon) in Mongolia was conducted across their range during November 2002. A country-wide population of 20,226 was estimated. Approximately 7% of Mongolia's 34,873 sq. km Agali range was surveyed. This was Mongolia's first repeatable survey for monitoring purposes. Other population estimates have been made, but the survey protocols were not given, making them unrepeatable and unusable for monitoring population trend. Population trend was established for a number of specific survey sites by comparing data collected during this survey with those done earlier in which the protocols were described. Population levels in some areas were depressed while in other areas population trend was stable or increasing. If the Mongolian Government implements a country-wide and site-specific Argali sustainable use management plan, potentially between 202-404 trophy rams could be harvested annually. -

Tornero Et Al., Jhumanevolutio

The altitudinal mobility of wild sheep at the Epigravettian site of Kalavan 1 (Lesser Caucasus, Armenia): evidence from a sequential isotopic analysis in tooth enamel Carlos Tornero, Marie Balasse, Adrian Balasescu, Chataigner Chataigner, Boris Gasparyan, Cyril Montoya To cite this version: Carlos Tornero, Marie Balasse, Adrian Balasescu, Chataigner Chataigner, Boris Gasparyan, et al.. The altitudinal mobility of wild sheep at the Epigravettian site of Kalavan 1 (Lesser Caucasus, Armenia): evidence from a sequential isotopic analysis in tooth enamel. Journal of Human Evolution, Elsevier, 2016, 10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.05.001. halshs-01473156 HAL Id: halshs-01473156 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01473156 Submitted on 2 Apr 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303923620 The altitudinal mobility of wild sheep at the Epigravettian site of Kalavan 1 (Lesser Caucasus, Armenia): Evidence from... Article in Journal of Human -

By Douglas P. Klein with Plates by G.A. Abrams and P.L. Hill U.S. Geological Survey, Denver, Colorado

U.S DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY STRUCTURE OF THE BASINS AND RANGES, SOUTHWEST NEW MEXICO, AN INTERPRETATION OF SEISMIC VELOCITY SECTIONS by Douglas P. Klein with plates by G.A. Abrams and P.L. Hill U.S. Geological Survey, Denver, Colorado Open-file Report 95-506 1995 This report is preliminary and has not been edited or reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards. The use of trade, product, or firm names in this papers is for descriptive purposes only, and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. STRUCTURE OF THE BASINS AND RANGES, SOUTHWEST NEW MEXICO, AN INTERPRETATION OF SEISMIC VELOCITY SECTIONS by Douglas P. Klein CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................. 1 DEEP SEISMIC CRUSTAL STUDIES .................................. 4 SEISMIC REFRACTION DATA ....................................... 7 RELIABILITY OF VELOCITY STRUCTURE ............................. 9 CHARACTER OF THE SEISMIC VELOCITY SECTION ..................... 13 DRILL HOLE DATA ............................................... 16 BASIN DEPOSITS AND BEDROCK STRUCTURE .......................... 20 Line 1 - Playas Valley ................................... 21 Cowboy Rim caldera .................................. 23 Valley floor ........................................ 24 Line 2 - San Luis Valley through the Alamo Hueco Mountains ....................................... 25 San Luis Valley ..................................... 26 San Luis and Whitewater Mountains ................... 26 Southern -

Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus

STATUS AND PROTECTION OF GLOBALLY THREATENED SPECIES IN THE CAUCASUS CEPF Biodiversity Investments in the Caucasus Hotspot 2004-2009 Edited by Nugzar Zazanashvili and David Mallon Tbilisi 2009 The contents of this book do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of CEPF, WWF, or their sponsoring organizations. Neither the CEPF, WWF nor any other entities thereof, assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product or process disclosed in this book. Citation: Zazanashvili, N. and Mallon, D. (Editors) 2009. Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus. Tbilisi: CEPF, WWF. Contour Ltd., 232 pp. ISBN 978-9941-0-2203-6 Design and printing Contour Ltd. 8, Kargareteli st., 0164 Tbilisi, Georgia December 2009 The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. This book shows the effort of the Caucasus NGOs, experts, scientific institutions and governmental agencies for conserving globally threatened species in the Caucasus: CEPF investments in the region made it possible for the first time to carry out simultaneous assessments of species’ populations at national and regional scales, setting up strategies and developing action plans for their survival, as well as implementation of some urgent conservation measures. Contents Foreword 7 Acknowledgments 8 Introduction CEPF Investment in the Caucasus Hotspot A. W. Tordoff, N. Zazanashvili, M. Bitsadze, K. Manvelyan, E. Askerov, V. Krever, S. Kalem, B. Avcioglu, S. Galstyan and R. Mnatsekanov 9 The Caucasus Hotspot N. -

Chapter 1 - Introduction

EURASIAN MIDDLE AND LATE MIOCENE HOMINOID PALEOBIOGEOGRAPHY AND THE GEOGRAPHIC ORIGINS OF THE HOMININAE by Mariam C. Nargolwalla A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Anthropology University of Toronto © Copyright by M. Nargolwalla (2009) Eurasian Middle and Late Miocene Hominoid Paleobiogeography and the Geographic Origins of the Homininae Mariam C. Nargolwalla Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology University of Toronto 2009 Abstract The origin and diversification of great apes and humans is among the most researched and debated series of events in the evolutionary history of the Primates. A fundamental part of understanding these events involves reconstructing paleoenvironmental and paleogeographic patterns in the Eurasian Miocene; a time period and geographic expanse rich in evidence of lineage origins and dispersals of numerous mammalian lineages, including apes. Traditionally, the geographic origin of the African ape and human lineage is considered to have occurred in Africa, however, an alternative hypothesis favouring a Eurasian origin has been proposed. This hypothesis suggests that that after an initial dispersal from Africa to Eurasia at ~17Ma and subsequent radiation from Spain to China, fossil apes disperse back to Africa at least once and found the African ape and human lineage in the late Miocene. The purpose of this study is to test the Eurasian origin hypothesis through the analysis of spatial and temporal patterns of distribution, in situ evolution, interprovincial and intercontinental dispersals of Eurasian terrestrial mammals in response to environmental factors. Using the NOW and Paleobiology databases, together with data collected through survey and excavation of middle and late Miocene vertebrate localities in Hungary and Romania, taphonomic bias and sampling completeness of Eurasian faunas are assessed. -

Science Newsletter

Mojave National Preserve National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Sweeney Granite Mountains Desert Research Center Science Newsletter Updates on respiratory disease affecting desert bighorn sheep in and near Mojave National Preserve 1 1 Clinton W. Epps , Daniella Dekelaita , and Brian Dugovich2 Desert bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis nelsoni) are an iconic mammal of the desert southwest and are found in small mountain ranges scattered across Mojave National Preserve (Preserve) and nearby desert habitats in southeastern California. In many areas, they are the only large native herbivore that can persist, inhabiting places that are too hot, dry, and sparsely vegetated for deer. California is thought to be home to ~3000-5000 desert bighorn in total (1); desert bighorn sheep are uniquely adapted for the harsh environment of the southwest deserts and populations appear to be resilient in spite of threats from poaching, climate change, drought, and habitat fragmentation (2, 3). In the Mojave Desert, bighorn sheep populations are strongly fragmented by expanses of flat desert between Figure 1. Map of Mojave National Preserve and nearby areas in southeastern California, mountain ranges, and in some cases, by showing mountain ranges (white polygons) where respiratory disease of bighorn sheep is being studied using GPS collars, remote cameras, disease screening of captured animals, behavioral and physical barriers such as fecal DNA, immunological and genetic measures, and other methods. The respiratory interstate highways (4). Yet, southeastern pathogen Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae was first reported at Old Dad Peak in spring of 2013 (large red star); current infection or past exposure has been confirmed at other red-starred California, including the Preserve, represents the ranges. -

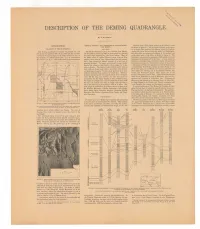

Description of the Deming Quadrangle

DESCRIPTION OF THE DEMING QUADRANGLE, By N. H. Darton. INTRODUCTION. GENERAL GEOLOGY AND GEOGRAPHY OF SOUTHWESTERN Paleozoic rocks. The general relations of the Paleozoic rocks NEW MEXICO. are shown in figure 3. 2 All the earlier Paleozoic rocks appear RELATIONS OF THE QUADRANGLE. STRUCTURE. to be absent from northern New Mexico, where the Pennsyl- The Deming quadrangle is bounded by parallels 32° and The Rocky Mountains extend into northern New Mexico, vanian beds lie on the pre-Cambrian rocks, but Mississippian 32° 30' and by meridians 107° 30' and 108° and thus includes but the southern part of the State is characterized by detached and older rocks are extensively developed in the southern and one-fourth of a square degree of the earth's surface, an area, in mountain ridges separated by wide desert bolsons. Many of southwestern parts of the State, as shown in figure 3. The that latitude, of 1,008.69 square miles. It is in southwestern the ridges consist of uplifted Paleozoic strata lying on older Cambrian is represented by sandstone, which appears to extend New Mexico (see fig. 1), a few miles north of the international granites, but in some of them Mesozoic strata also are exposed, throughout the southern half of the State. At some places the and a large amount of volcanic material of several ages is sandstone has yielded Upper Cambrian fossils, and glauconite 109° 108° 107" generally included. The strata are deformed to some extent. in disseminated grains is a characteristic feature in many beds. Some of the ridges are fault blocks; others appear to be due Limestones of Ordovician age outcrop in all the larger ranges solely to flexure. -

REPORT on TRANSBOUNDARY CONSERVATION HOTSPOTS for the CENTRAL ASIAN MAMMALS INITIATIVE (Prepared by the Secretariat)

CONVENTION ON UNEP/CMS/COP13/Inf.27 MIGRATORY 8 January 2020 SPECIES Original: English 13th MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES Gandhinagar, India, 17 - 22 February 2020 Agenda Item 26.3 REPORT ON TRANSBOUNDARY CONSERVATION HOTSPOTS FOR THE CENTRAL ASIAN MAMMALS INITIATIVE (Prepared by the Secretariat) Summary: This report was developed with funding from the Government of Switzerland within the frame of the Central Asian Mammals Initiative (CAMI) (Doc. 26.3.5) to identify transboundary conservation hotspots and develop recommendations for their conservation. The report builds on existing projects, in particular, the CAMI Linear Infrastructure and Migration Atlas (see Inf.Doc.19) and focusses on the same species and geographical area. The study was discussed during the CAMI Range State Meeting held from 25-28 September 2019 in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia where participants reviewed the pre-identified areas. Their comments are incorporated in this report. Participants also provided new information about important transboundary sites from Bhutan, India, Nepal and Pakistan and recommended to send the report for final review to Range States and experts. It was also recommended that the final report covers all CAMI species as adopted at COP13. This report is therefore a final draft with the last step to expand the geographical and species scope and finalize the report to be undertaken after COP13. Mapping Transboundary Conservation Hotspots for the Central Asian Mammals Initiative Photo credit: Viktor Lukarevsky Report – Draft 5 incorporating comments made during the CAMI Range States Meeting on 25-28 September 2019 in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. The report does not yet consider the Urial, Persian leopard and Gobi bear as CAMI species pending decision at the CMS COP13, as well as the proposed expansion of the geographic and species scope to include the entire CAMI region in this study.