Arginyltransferase Is an ATP-Independent Self-Regulating Enzyme That Forms Distinct Functional Complexes in Vivo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enzymatic Encoding Methods for Efficient Synthesis Of

(19) TZZ__T (11) EP 1 957 644 B1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (45) Date of publication and mention (51) Int Cl.: of the grant of the patent: C12N 15/10 (2006.01) C12Q 1/68 (2006.01) 01.12.2010 Bulletin 2010/48 C40B 40/06 (2006.01) C40B 50/06 (2006.01) (21) Application number: 06818144.5 (86) International application number: PCT/DK2006/000685 (22) Date of filing: 01.12.2006 (87) International publication number: WO 2007/062664 (07.06.2007 Gazette 2007/23) (54) ENZYMATIC ENCODING METHODS FOR EFFICIENT SYNTHESIS OF LARGE LIBRARIES ENZYMVERMITTELNDE KODIERUNGSMETHODEN FÜR EINE EFFIZIENTE SYNTHESE VON GROSSEN BIBLIOTHEKEN PROCEDES DE CODAGE ENZYMATIQUE DESTINES A LA SYNTHESE EFFICACE DE BIBLIOTHEQUES IMPORTANTES (84) Designated Contracting States: • GOLDBECH, Anne AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB GR DK-2200 Copenhagen N (DK) HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC NL PL PT RO SE SI • DE LEON, Daen SK TR DK-2300 Copenhagen S (DK) Designated Extension States: • KALDOR, Ditte Kievsmose AL BA HR MK RS DK-2880 Bagsvaerd (DK) • SLØK, Frank Abilgaard (30) Priority: 01.12.2005 DK 200501704 DK-3450 Allerød (DK) 02.12.2005 US 741490 P • HUSEMOEN, Birgitte Nystrup DK-2500 Valby (DK) (43) Date of publication of application: • DOLBERG, Johannes 20.08.2008 Bulletin 2008/34 DK-1674 Copenhagen V (DK) • JENSEN, Kim Birkebæk (73) Proprietor: Nuevolution A/S DK-2610 Rødovre (DK) 2100 Copenhagen 0 (DK) • PETERSEN, Lene DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø (DK) (72) Inventors: • NØRREGAARD-MADSEN, Mads • FRANCH, Thomas DK-3460 Birkerød (DK) DK-3070 Snekkersten (DK) • GODSKESEN, -

Supplementary Table S4. FGA Co-Expressed Gene List in LUAD

Supplementary Table S4. FGA co-expressed gene list in LUAD tumors Symbol R Locus Description FGG 0.919 4q28 fibrinogen gamma chain FGL1 0.635 8p22 fibrinogen-like 1 SLC7A2 0.536 8p22 solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 DUSP4 0.521 8p12-p11 dual specificity phosphatase 4 HAL 0.51 12q22-q24.1histidine ammonia-lyase PDE4D 0.499 5q12 phosphodiesterase 4D, cAMP-specific FURIN 0.497 15q26.1 furin (paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme) CPS1 0.49 2q35 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1, mitochondrial TESC 0.478 12q24.22 tescalcin INHA 0.465 2q35 inhibin, alpha S100P 0.461 4p16 S100 calcium binding protein P VPS37A 0.447 8p22 vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) SLC16A14 0.447 2q36.3 solute carrier family 16, member 14 PPARGC1A 0.443 4p15.1 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha SIK1 0.435 21q22.3 salt-inducible kinase 1 IRS2 0.434 13q34 insulin receptor substrate 2 RND1 0.433 12q12 Rho family GTPase 1 HGD 0.433 3q13.33 homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase PTP4A1 0.432 6q12 protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 C8orf4 0.428 8p11.2 chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 DDC 0.427 7p12.2 dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) TACC2 0.427 10q26 transforming, acidic coiled-coil containing protein 2 MUC13 0.422 3q21.2 mucin 13, cell surface associated C5 0.412 9q33-q34 complement component 5 NR4A2 0.412 2q22-q23 nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 EYS 0.411 6q12 eyes shut homolog (Drosophila) GPX2 0.406 14q24.1 glutathione peroxidase -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2003/0082511 A1 Brown Et Al

US 20030082511A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2003/0082511 A1 Brown et al. (43) Pub. Date: May 1, 2003 (54) IDENTIFICATION OF MODULATORY Publication Classification MOLECULES USING INDUCIBLE PROMOTERS (51) Int. Cl." ............................... C12O 1/00; C12O 1/68 (52) U.S. Cl. ..................................................... 435/4; 435/6 (76) Inventors: Steven J. Brown, San Diego, CA (US); Damien J. Dunnington, San Diego, CA (US); Imran Clark, San Diego, CA (57) ABSTRACT (US) Correspondence Address: Methods for identifying an ion channel modulator, a target David B. Waller & Associates membrane receptor modulator molecule, and other modula 5677 Oberlin Drive tory molecules are disclosed, as well as cells and vectors for Suit 214 use in those methods. A polynucleotide encoding target is San Diego, CA 92121 (US) provided in a cell under control of an inducible promoter, and candidate modulatory molecules are contacted with the (21) Appl. No.: 09/965,201 cell after induction of the promoter to ascertain whether a change in a measurable physiological parameter occurs as a (22) Filed: Sep. 25, 2001 result of the candidate modulatory molecule. Patent Application Publication May 1, 2003 Sheet 1 of 8 US 2003/0082511 A1 KCNC1 cDNA F.G. 1 Patent Application Publication May 1, 2003 Sheet 2 of 8 US 2003/0082511 A1 49 - -9 G C EH H EH N t R M h so as se W M M MP N FIG.2 Patent Application Publication May 1, 2003 Sheet 3 of 8 US 2003/0082511 A1 FG. 3 Patent Application Publication May 1, 2003 Sheet 4 of 8 US 2003/0082511 A1 KCNC1 ITREXCHO KC 150 mM KC 2000000 so 100 mM induced Uninduced Steady state O 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 Time (seconds) FIG. -

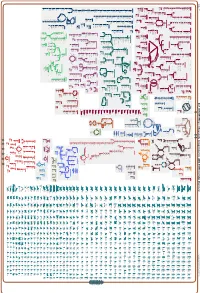

Generate Metabolic Map Poster

Authors: Pallavi Subhraveti Ron Caspi Peter Midford Peter D Karp An online version of this diagram is available at BioCyc.org. Biosynthetic pathways are positioned in the left of the cytoplasm, degradative pathways on the right, and reactions not assigned to any pathway are in the far right of the cytoplasm. Transporters and membrane proteins are shown on the membrane. Ingrid Keseler Periplasmic (where appropriate) and extracellular reactions and proteins may also be shown. Pathways are colored according to their cellular function. Gcf_003855395Cyc: Shewanella livingstonensis LMG 19866 Cellular Overview Connections between pathways are omitted for legibility. -

Arginyltransferase Suppresses Cell Tumorigenic Potential and Inversely Correlates with Metastases in Human Cancers

Oncogene (2016) 35, 4058–4068 © 2016 Macmillan Publishers Limited, part of Springer Nature. All rights reserved 0950-9232/16 www.nature.com/onc ORIGINAL ARTICLE Arginyltransferase suppresses cell tumorigenic potential and inversely correlates with metastases in human cancers RRai1,7, F Zhang1,2,7, K Colavita1, NA Leu1, S Kurosaka1, A Kumar2, MD Birnbaum2,BGyőrffy3,4, DW Dong5, M Shtutman6 and A Kashina1 Arginylation is an emerging post-translational modification mediated by arginyltransferase (ATE1) that is essential for mammalian embryogenesis and regulation of the cytoskeleton. Here, we discovered that Ate1-knockout (KO) embryonic fibroblasts exhibit tumorigenic properties, including abnormally rapid contact-independent growth, reduced ability to form cell–cell contacts and chromosomal aberrations. Ate1-KO fibroblasts can form large colonies in Matrigel and exhibit invasive behavior, unlike wild-type fibroblasts. Furthermore, Ate1-KO cells form tumors in subcutaneous xenograft assays in immunocompromised mice. Abnormal growth in these cells can be partially rescued by reintroduction of stably expressed specific Ate1 isoforms, which also reduce the ability of these cells to form tumors. Tumor array studies and bioinformatics analysis show that Ate1 is downregulated in several types of human cancer samples at the protein level, and that its transcription level inversely correlates with metastatic progression and patient survival. We conclude that Ate1-KO results in carcinogenic transformation of cultured fibroblasts, suggesting that in addition -

Supplementary Table 1A. Genes Significantly Altered in A4573 ESFT

Supplementary Table 1A. Genes significantly altered in A4573 ESFT cells following BMI-1knockdown genesymbol genedescription siControl siBMI1 FC Direction P-value AASS aminoadipate-semialdehyde synthase | tetra-peptide repeat homeobox-like6.68 7.24 1.5 Up 0.007 ABCA2 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family A (ABC1), member 2 | neural5.44 proliferation,6.3 differentiation1.8 and Upcontrol, 1 0.006 ABHD4 abhydrolase domain containing 4 7.51 6.69 1.8 Down 0.002 ACACA acetyl-Coenzyme A carboxylase alpha | peroxiredoxin 5 | similar6.2 to High mobility7.26 group2.1 protein UpB1 (High mobility0.009 group protein 1) (HMG-1) (Amphoterin) (Heparin-binding protein p30) | Coenzyme A synthase ACAD9 acyl-Coenzyme A dehydrogenase family, member 9 9.25 8.59 1.6 Down 0.008 ACBD3 acyl-Coenzyme A binding domain containing 3 7.89 8.53 1.6 Up 0.008 ACCN2 amiloride-sensitive cation channel 2, neuronal 5.47 6.28 1.8 Up 0.005 ACIN1 apoptotic chromatin condensation inducer 1 7.15 7.79 1.6 Up 0.008 ACPL2 acid phosphatase-like 2 6.04 7.6 2.9 Up 0.000 ACSL4 acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 6.72 5.8 1.9 Down 0.001 ACTA2 actin, alpha 2, smooth muscle, aorta 9.18 8.44 1.7 Down 0.003 ACYP1 acylphosphatase 1, erythrocyte (common) type 7.09 7.66 1.5 Up 0.009 ADA adenosine deaminase 6.34 7.1 1.7 Up 0.009 ADAL adenosine deaminase-like 7.88 6.89 2.0 Down 0.006 ADAMTS1 ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif, 1 6.57 7.65 2.1 Up 0.000 ADARB1 adenosine deaminase, RNA-specific, B1 (RED1 homolog rat) 6.49 7.13 1.6 Up 0.008 ADCY9 adenylate cyclase 9 6.5 7.18 -

Gene Expression Profiling Identifies FKBP39 As an Inhibitor of Autophagy in Larval Drosophila Fat Body

Cell Death and Differentiation (2007) 14, 1181–1190 & 2007 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 1350-9047/07 $30.00 www.nature.com/cdd Gene expression profiling identifies FKBP39 as an inhibitor of autophagy in larval Drosophila fat body G Juha´sz*,1,2, LG Puska´s3, O Komonyi4,BE´ rdi1, P Maro´y4, TP Neufeld2 and M Sass1 In Drosophila, the fat body undergoes a massive burst of autophagy at the end of larval development in preparation for the pupal transition. To identify genes involved in this process, we carried out a microarray analysis. We found that mRNA levels of the homologs of Atg8, the coat protein of early autophagic structures, and lysosomal hydrolases were upregulated, consistent with previous results. Genes encoding mitochondrial proteins and many chaperones were downregulated, including the inhibitor of eIF2alpha kinases and the peptidyl-prolyl cis–trans isomerase FK506-binding protein of 39 kDa (FKBP39). Genetic manipulation of FKBP39 expression had a significant effect on autophagy, potentially through modulation of the transcription factor Foxo. Accordingly, we found that Foxo mutants cannot properly undergo autophagy in response to starvation, and that overexpression of Foxo induces autophagy. Cell Death and Differentiation (2007) 14, 1181–1190. doi:10.1038/sj.cdd.4402123; published online 16 March 2007 Autophagy is the degradation of self material by lysosomes. adulthood.5–8 The fat body, an analog of the human liver, is a As a primary cellular defense response, it is activated by polytenic tissue that grows in mass approximately 200-fold in nitrogen or amino-acid starvation from yeast to mammals, and feeding Drosophila larvae during the larval stages. -

Setd1 Histone 3 Lysine 4 Methyltransferase Complex Components in Epigenetic Regulation

SETD1 HISTONE 3 LYSINE 4 METHYLTRANSFERASE COMPLEX COMPONENTS IN EPIGENETIC REGULATION Patricia A. Pick-Franke Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Indiana University December 2010 Accepted by the Faculty of Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science. _____________________________________ David Skalnik, Ph.D., Chair _____________________________________ Kristin Chun, Ph.D. Master’s Thesis Committee _____________________________________ Simon Rhodes, Ph.D. ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my sons, Zachary and Zephaniah who give me great joy, hope and continuous inspiration. I can only hope that I successfully set a good example demonstrating that one can truly accomplish anything, if you never give up and reach for your dreams. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my committee members Dr. Skalnik, Dr. Chun and Dr. Rhodes for allowing me to complete this dissertation. They have been incredibly generous with their flexibility. I must make a special thank you to Jeanette McClintock, who willingly gave her expertise in statistical analysis with the Cfp1 microarray data along with encouragement, support and guidance to complete this work. I would like to thank Courtney Tate for her ceaseless willingness to share ideas, and her methods and materials, and Erika Dolbrota for her generous instruction as well as the name of a good doctor. I would also like to acknowledge the superb mentorship of Dr. Jeon Heong Lee, PhD and the contagious passion and excitement for the life of science of Dr. -

Arginyltransferase ATE1 Catalyzes Midchain Arginylation of Proteins at Side Chain Carboxylates in Vivo

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Chemistry & Biology Brief Communication Arginyltransferase ATE1 Catalyzes Midchain Arginylation of Proteins at Side Chain Carboxylates In Vivo Junling Wang,1 Xuemei Han,2 Catherine C.L. Wong,2 Hong Cheng,3 Aaron Aslanian,2 Tao Xu,2 Paul Leavis,4 Heinrich Roder,3 Lizbeth Hedstrom,5 John R. Yates III,2 and Anna Kashina1,* 1Department of Animal Biology, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, 3800 Spruce Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA 2The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 N. Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, CA 92037, USA 3Fox Chase Cancer Center, 333 Cottman Avenue, Philadelphia, PA, 19111, USA 4Tufts University School of Medicine, 145 Harrison Avenue, Boston, MA 02111, USA 5Department of Biology and Department of Chemistry, Brandeis University, 415 South Street, Waltham, MA 02454, USA *Correspondence: [email protected] http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.12.017 SUMMARY few N-terminally arginylated proteins have been identified in vivo, despite the fact that overall estimates suggest that a large per- Arginylation is an emerging posttranslational modifi- centage of the proteome may undergo arginylation (Wong cation mediated by Arg-tRNA-protein-transferase et al., 2007). These results leave open the possibility that arginy- (ATE1). It is believed that ATE1 links Arg solely to lation may also occur at internal sites within intact proteins, the N terminus of proteins, requiring prior proteolysis which have not been commonly considered during previous or action by Met-aminopeptidases to expose the argi- identification strategies. -

Liat1, an Arginyltransferase-Binding Protein Whose Evolution Among Primates Involved Changes in the Numbers of Its 10-Residue Repeats

Liat1, an arginyltransferase-binding protein whose evolution among primates involved changes in the numbers of its 10-residue repeats Christopher S. Brower1, Connor E. Rosen, Richard H. Jones2, Brandon C. Wadas, Konstantin I. Piatkov, and Alexander Varshavsky3 Division of Biology, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125 Contributed by Alexander Varshavsky, October 13, 2014 (sent for review October 6, 2014; reviewed by Wolfgang Baumeister and Avram Hershko) The arginyltransferase Ate1 is a component of the N-end rule In eukaryotes, the N-end rule pathway consists of two branches. pathway, which recognizes proteins containing N-terminal degra- One branch, called the Ac/N-end rule pathway, targets proteins for α dation signals called N-degrons, polyubiquitylates these proteins, degradation through their N -terminally acetylated (Nt-acetylated) and thereby causes their degradation by the proteasome. At least residues (Fig. 1B) (2, 3, 12). Degradation signals and E3 Ub ligases six isoforms of mouse Ate1 are produced through alternative of the Ac/N-end rule pathway are called Ac/N-degrons and Ac/N- splicing of Ate1 pre-mRNA. We identified a previously uncharacter- recognins, respectively. Nt-acetylation of cellular proteins is appar- ized mouse protein, termed Liat1 (ligand of Ate1), that interacts ently irreversible, in contrast to acetylation-deacetylation of internal with Ate1 but does not appear to be its arginylation substrate. Liat1 Lys residues. Approximately 90% of human proteins are cotrans- has a higher affinity for the isoforms Ate11A7A and Ate11B7A.Liat1 lationally Nt-acetylated by ribosome-associated Nt-acetylases (13). stimulated the in vitro N-terminal arginylation of a model substrate Posttranslational Nt-acetylation occurs as well. -

Supplementary Figure 1. Rpod Sequence Alignment. Protein Sequence Alignment Was Performed for Rpod from Three Species, Pseudoruegeria Sp

J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.4014/jmb.1911.11006 J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.4014/jmb.2003.03025 Supplementary Figure 1. RpoD sequence alignment. Protein sequence alignment was performed for RpoD from three species, Pseudoruegeria sp. M32A2M (FPS10_24745, this study), Ruegeria pomeroyi (NCBI RefSeq: WP_011047484.1), and Escherichia coli (NCBI RefSeq: NP_417539.1). Multalin version 5.4.1 was used for the analysis. Subregion 2 and 4 are represented in a rectangle, and the helix-turn-helix motif in subregion 4 is highlighted in red. The amino acid degeneration from any of the three was highlighted in light gray and the sequence degeneration between Pseudoruegeria sp. M32A2M and R. pomeroyi is highlighted in dark gray. The substituted two amino acids into HTH motif (K578Q and D581S) against E. coli were marked as asterisk. Supplementary Table 1. Genome assembly statistics Categories Pseudoruegeria sp. M32A2M Number of scaffolds less than 1,000 bp 0 Number of scaffolds between 1,000 bp –10,000 bp 39 Number of scaffolds between 10,000 bp – 100,000 bp 38 Number of scaffolds larger than 100,000 bp 14 Number of scaffolds 91 Total assembled length (bp) 5,466,515 G+C contents (%) 62.4 N50 (bp) 249,384 Minimum length of scaffold (bp) 1,015 Maximum length of scaffold (bp) 733,566 Total Ns included in the draft genome 2,158 Supplementary Table 2. The list of gene annotation and its functional categorization in Pseudoruegeria sp. -

Full-Term Pregnancy Induces a Specific Genomic Signature in the Human Breast

51 Full-term Pregnancy Induces a Specific Genomic Signature in the Human Breast Jose Russo, Gabriela A. Balogh, and Irma H. Russo and the Fox Chase Cancer Center Hospital NetworkParticipants Breast Cancer Research Laboratory, Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Abstract Breast cancer riskhas traditionally been linkedto were analyzed using ImaGene software version 4.2. nulliparity or late first full-term pregnancy, whereas Normalization and statistical analysis were carried out young age at first childbirth, multiparity, and breast- using Linear Models for Microarrays and GeneSight feeding are associated with a reduced risk. Early software for hierarchical clustering. The parous con- pregnancy confers protection by inducing breast trol group contained 2,541 gene sequences represent- differentiation, which imprints a specific and perma- ing 18 biological processes that were differentially nent genomic signature in experimental rodent expressed in comparison with the other three groups. models. For testing whether the same phenomenon Hierarchical clustering of these genes revealed that was detectable in the atrophic breast of postmeno- the combined parity/absence of breast cancer data pausal parous women, we designed a case-control generated a distinct genomic profile that differed from study for the analysis of the gene expression profile those of the breast cancer groups, irrespective of parity of RNA extracted from epithelial cells microdissected history, and from the nulliparous cancer-free group, from normal breast tissues obtained from 18 parous which has been traditionally identified as a high-risk and 7 nulliparous women free of breast pathology group. The signature that identifies those women in (controls), and 41 parous and 8 nulliparous women whom parity has been protective will serve as a with history of breast cancer (cases).