Of Macedonia, Macedonians, and Macedonian Kings The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Detailed Fact Sheet 19.Pdf

THE RESORT Imagine overlooking the azure sea sparkling from every angle you stand. Imagine sinking your toes in the warm sand, feeling carefree, and free to self-care. Even so, there are places that cannot be fully framed in our imagination. It is only the soul that can genuinely recognize their blessings emerging from their land, their skyline and the smile of their people. Miraggio Thermal Spa Resort is one of them, a luxury spa resort in Halkidiki; a Greek Eden of unpretentious comfort lying amphitheatrically at the tip of the Kassandra peninsula, an ideal destination for families. This seafront enclave of well being and countless amenities descends on a lovely hill slope across 330 acres at one of the most unspoiled and least exploited areas in North Greece. Location The region is situated at the northern Aegean sea and shaped like a three-fingers palm; Kassandra, Sithonia and Mount Athos are the names of its peninsulas and each one of them has something unique to offer. Due to its easy access from different parts of Europe and Thessaloniki, and thanks to its recognized and contemporary hospitality infrastructure, Halkidiki is one of the ideal locations for holidays, international conferences, incentives and cruises. Weather 280 sunny days per year; mild Mediterranean microclimate. Neighborhood & Access Miraggio Thermal Spa Resort abstains from Thessaloniki airport 120 km. The second largest city of Greece is charming, ancient and vibrant, lies on the shore of the Thermaic Gulf and welcomes warmly its visitors. 63085 Paliouri, Kanistro,Halkidiki GR Reservations: [email protected] T: +30 2374440 000 E: [email protected] F: +30 23744 40 001 W: www.miraggio.gr Dining & Bars At Miraggio Thermal Spa Resort, a marvelous array of kitchen venues, food services, and bars is offered. -

The GIS Application to the Spatial Data Organization of the Necropolis of Poseidonia-Paestum (Salerno, Italy)

The GIS Application to the Spatial Data Organization of the Necropolis of Poseidonia-Paestum (Salerno, Italy) A. SANTORIELLO', F. U. SCELZA', R. GALLOTTP, R. BOVE\ L. SIRANGELO', A. PONTRANDOLFO' ' University of Salemo, Department of Cultural Heritage, Laboratory of Archaeology "M. Napoli", Italy ' CRdC "Innova", Department of Cultural Heritage, University of Salemo, Italy ' Independent Software Developer ABSTRACT This paper concerns about the spatial organization and the thematic management of the Poseidonia and Paestum's urban funeral areas. The wide archaeological heritage, investigated since the beginning of XIX century, had been studied using different research methodologies. These studies led to several inhomogeneous documents. First of all, we have to notice the absence of a general topographical map concerning the exact localization of each grave. In front of this scenario, the aim for the researcher consisted in the documentary source's collection and the integration in order to construct an unique cartographical base to use as a corner stone for the Paestum 's plain. This base has been realized through the acquisition of multi-temporal and multi- scalar supports. These different data have been organized within a Geographical Information System, according to the same cartographical projection system. The burial ground's geo-localisation has been realized through survey control operations, carried out by a satellite positioning system (GPS- Glonass) with subcentrimetrical resolution. The second phase of the research aimed to the database construction in order to collect analytical records, relevant to each tomb, and to link the archaeological data to the geographical entities previously created. The target was to create an informative layer, selective and comprehensive at the same time, able to process specific thematic questions, analysis of singular funerary context and comparative examination of the entire necropolis. -

Agricultural Practices in Ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman Period

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Hellenic University: IHU Open Access Repository Agricultural practices in ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman period Evangelos Kamanatzis SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies January 2018 Thessaloniki – Greece Student Name: Evangelos Kamanatzis SID: 2201150001 Supervisor: Prof. Manolis Manoledakis I hereby declare that the work submitted is mine and that where I have made use of another’s work, I have attributed the source(s) according to the Regulations set in the Student’s Handbook. January 2018 Thessaloniki - Greece Abstract This dissertation was written as part of the MA in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies at the International Hellenic University. The aim of this dissertation is to collect as much information as possible on agricultural practices in Macedonia from prehistory to Roman times and examine them within their social and cultural context. Chapter 1 will offer a general introduction to the aims and methodology of this thesis. This chapter will also provide information on the geography, climate and natural resources of ancient Macedonia from prehistoric times. We will them continue with a concise social and cultural history of Macedonia from prehistory to the Roman conquest. This is important in order to achieve a good understanding of all these social and cultural processes that are directly or indirectly related with the exploitation of land and agriculture in Macedonia through time. In chapter 2, we are going to look briefly into the origins of agriculture in Macedonia and then explore the most important types of agricultural products (i.e. -

The Depiction of Acromegaly in Ancient Greek and Hellenistic Art

HORMONES 2016, 15(4):570-571 Letter to the Editor The depiction of acromegaly in ancient Greek and Hellenistic art Konstantinos Laios,1 Maria Zozolou,2 Konstantinos Markatos,3 Marianna Karamanou,1 George Androutsos1 1Biomedical Research Foundation, Academy of Athens, 2Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, 3Henry Dunant Hospital, Orthopedics Department, Athens, Greece Dear Editor, Hellenistic age (323-31 BC), all with the characteris- tics of acromegaly, have been found in various parts In 1886, Pierre Marie (1853-1940) published the of the ancient Greek world of the times.2 All these first accurate scientific description of acromegaly while also coining the term that we now employ (ac- romegaly today being used when the disease appears in adulthood, and gigantism when it is seen in child- hood). While several other physicians had, previous to Marie, spoken about this disease, starting with the Dutch physician Johann Wier (ca. 1515-1588),1 numerous representations of the human figure with characteristics of acromegaly were fashioned by an- cient Greek and Hellenistic craftsmen. For example, five terracotta male figurines of the ancient Greek era (Alexandria, Graeco-Roman Museum: 10039 Figure 1 and 22631, Delos, Archaeological Museum: ǹ9DWLFDQR0XVHR*UHJRULDQR(WUXVFR Geneva, Collection De Candolle: 21) and three ter- racotta female figurines (Taranto, Museo Nazionale Archeologico, Figure 2 Athens, Benaki Museum: 8210, Tarsus, Tarsus Museum: 35-1369) dated to the Key words: Acromegaly, Ancient Greek art, Ancient Greek medicine, Hellenistic art, Terracotta figurines Address for correspondence: Konstantinos Laios PhD, 1 Athinodorou Str., Kato Petralona, 118 53 Athens, Attiki, Greece; Tel.: +30 6947091434, Fax: +30 2103474338, E-mail: [email protected] Figure 1. -

Is the Gulf of Taranto an Historic Bay?*

Ronzitti: Gulf of Taranto IS THE GULF OF TARANTO AN HISTORIC BAY?* Natalino Ronzitti** I. INTRODUCTION Italy's shores bordering the Ionian Sea, particularly the seg ment joining Cape Spartivento to Cape Santa Maria di Leuca, form a coastline which is deeply indented and cut into. The Gulf of Taranto is the major indentation along the Ionian coast. The line joining the two points of the entrance of the Gulf (Alice Point Cape Santa Maria di Leuca) is approximately sixty nautical miles in length. At its mid-point, the line joining Alice Point to Cape Santa Maria di Leuca is approximately sixty-three nautical miles from the innermost low-water line of the Gulf of Taranto coast. The Gulf of Taranto is a juridical bay because it meets the semi circular test set up by Article 7(2) of the 1958 Geneva Convention on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone. 1 Indeed, the waters embodied by the Gulf cover an area larger than that of the semi circle whose diameter is the line Alice Point-Cape Santa Maria di Leuca (the line joining the mouth of the Gulf). On April 26, 1977, Italy enacted a Decree causing straight baselines to be drawn along the coastline of the Italian Peninsula.2 A straight baseline, about sixty nautical miles long, was drawn along the entrance of the Gulf of Taranto between Cape Santa Maria di Leuca and Alice Point. The 1977 Decree justified the drawing of such a line by proclaiming the Gulf of Taranto an historic bay.3 The Decree, however, did not specify the grounds upon which the Gulf of Taranto was declared an historic bay. -

Case Studies in Reggio Calabria, Italy

Sustainable Development and Planning X 903 RIVER ANTHROPIZATION: CASE STUDIES IN REGGIO CALABRIA, ITALY ROSA VERSACI, FRANCESCA MINNITI, GIANDOMENICO FOTI, CATERINA CANALE & GIUSEPPINA CHIARA BARILLÀ DICEAM Department. Mediterranea University of Reggio Calabria, Italy ABSTRACT The considerable anthropic pressure that has affected most of Italian territory in the last 60 years has altered natural conditions of coasts and river, thus increasing exposure to environmental risks. For example, increase in soil waterproofing caused a reduction in hydrological losses with a rise in flood flows (with the same rainfall conditions), especially in urban areas. This issue is important in territories like Mediterranean region, that are prone to flooding events. From this point of view, recent advances in remote sensing and geographical information system (GIS) techniques allow us to analyze morphological changes occurred in river and in urban centers, in order to evaluate possible increases in environmental risks related to the anthropization process. This paper analyzes and describes the effects of anthropization process on some rivers in the southern area of the Reggio Calabria city (the Sant'Agata, Armo and Valanidi rivers). This is a heavily anthropized area due to the presence of the airport, highway and houses. The analysis was carried out using QGIS, through the comparison of cartography data of the last 60 years, which consists of aerophotogrammetry of 1955, provided by Italian Military Geographic Institute, and the latest satellite imagery provided by Google Earth Pro. Keywords: river anthropization, flooding risk, GIS, cartography data, Reggio Calabria. 1 INTRODUCTION The advance in anthropogenic pressure observed in Italy over the last 60 years [1], [2] has increased vulnerability of territory under the action of natural events such as floods [3]–[5], debris flow [6], [7], storms [8], [9] and coastal erosion [10], [11]. -

Fisheries in Greece

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT NOTE Directorate-General for Internal Policies of the Union Policy Department Structural and Cohesion Policies FISHERIES IN GREECE FISHERIES 11/04/2006 EN Directorate-General for Internal Policies of the Union Policy Department: Structural and Cohesion Policies FISHERIES FISHERIES IN GREECE NOTE Content: Document describing the fisheries sector in Greece for the Delegation of the Committee on Fisheries to Thessaloniki (3 to 6 June 2006). IPOL/B/PECH/NT/2006_02 11/04/2006 PE 369.028 EN This note was requested by the European Parliament’s Committee on Fisheries. This document has been published in the following languages: - Original: ES; - Translations: DE, EL, EN, IT. Author: Jesús Iborra Martín Policy Department Structural and Cohesion Policies Tel: +32 (0)284 45 66 Fax: +32 (0)284 69 29 E-mail: [email protected] Manuscript completed in April 2006. Copies may be obtained through: E-mail: [email protected] Intranet: http://www.ipolnet.ep.parl.union.eu/ipolnet/cms/lang/en/pid/456 Brussels, European Parliament, 2006. The opinions expressed in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the European Parliament. Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposes are authorised, provided the source is acknowledged and the publisher is given prior notice and sent a copy. CONTENTS 1. Introduction ...............................................................................................................................3 2. Geographical framework...........................................................................................................4 -

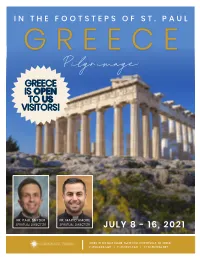

Pilgrimage GREECE IS OPEN to US VISITORS!

IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF ST. PAUL GREECE Pilgrimage GREECE IS OPEN TO US VISITORS! FR. PAUL SNYDER FR. MARIO AMORE SPIRITUAL DIRECTOR SPIRITUAL DIRECTOR JULY 8 - 16, 2021 41780 W SIX MILE ROAD, SUITE 1OO, NORTHVILLE, MI 48168 P: 866.468.1420 | F: 313.565.3621 | CTSCENTRAL.NET READY TO SEE THE WORLD? PRICING STARTING AT $1,699 PER PERSON, DOUBLE OCCUPANCY PRICE REFLECTS A $100 PER PERSON EARLY BOOKING SAVINGS FOR DEPOSITS RECEIVED BEFORE JUNE 11, 2021 & A $110 PER PERSON DISCOUNT FOR TOURS PAID ENTIRELY BY E-CHECK LEARN MORE & BOOK ONLINE: WWW.CTSCENTRAL.NET/GREECE-20220708 | TRIP ID 45177 | GROUP ID 246 QUESTIONS? VISIT CTSCENTRAL.NET TO BROWSE OUR FAQ’S OR CALL 866.468.1420 TO SPEAK TO A RESERVATIONS SPECIALIST. DAY 1: THURSDAY, JULY 8: OVERNIGHT FLIGHT FROM USA TO ATHENS, GREECE Depart the USA on an overnight flight. St. Paul the Apostle, the prolific writer of the New Testament letters, was one of the first Christian missionaries. Trace his journey through the ancient cities and pastoral countryside of Greece. DAY 2: FRIDAY, JULY 9: ARRIVE THESSALONIKI Arrive in Athens on your independent flights by 12:30pm.. Transfer on the provided bus from Athens to the hotel in Thessaloniki and meet your professional tour director. Celebrate Mass and enjoy a Welcome Dinner. Overnight Thessaloniki. DAY 3: SATURDAY, JULY 10: THESSALONIKI Tour Thessaloniki, Greece’s second largest city, sitting on the Thermaic Gulf of the Aegean Sea. Founded in 315 B.C.E. by King Kassandros, the city grew to be an important hub for trade in the ancient world. -

Stratigraphic Revision of Brindisi-Taranto Plain

Mem. Descr. Carta Geol. d’It. XC (2010), pp. 165-180, figg. 15 Stratigraphic revision of Brindisi-Taranto plain: hydrogeological implications Revisione stratigrafica della piana Brindisi-Taranto e sue implicazioni sull’assetto idrogeologico MARGIOTTA S. (*), MAZZONE F. (*), NEGRI S. (*) ABSTRACT - The studied area is located at the eastern and RIASSUNTO - In questo articolo si propone una revisione stra- western coastal border of the Brindisi-Taranto plain (Apulia, tigrafica delle unità della piana Brindisi – Taranto e se ne evi- Italy). In these pages, new detailed cross-sections are pre- denziano le implicazioni sull’assetto idrogeologico. Rilievi sented, based on surface surveys and subsurface analyses by geologici di superficie e del sottosuolo, sia attraverso l’osser- borehole and well data supplied by local agencies or obtained vazione diretta di carote di perforazioni sia mediante inda- by private research and scientific literature, integrated with gini ERT, hanno permesso di delineare gli assetti geologici e new ERT surveys. The lithostratigraphic units identified in di reinterpretare i numerosi dati di sondaggi a disposizione. the geological model have been ascribed to the respective hy- Definito il modello geologico sono state individuate le unità drogeologic units allowing for the identification of the main idrogeologiche che costituiscono i due acquiferi principali. aquifer systems: Il primo, profondo, soggiace tutta l’area di studio ed è costi- a deep aquifer that lies in the Mesozoic limestones, made tuito dai Calcari di Altamura mesozoici, permeabili per of fractured and karstic carbonates, and in the overlying fessurazione e carsismo, e dalle Calcareniti di Gravina pleisto- Lower Pleistocene calcarenite; ceniche, permeabili per porosità. -

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS from SOUTH ITALY and SICILY in the J

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS FROM SOUTH ITALY AND SICILY in the j. paul getty museum The free, online edition of this catalogue, available at http://www.getty.edu/publications/terracottas, includes zoomable high-resolution photography and a select number of 360° rotations; the ability to filter the catalogue by location, typology, and date; and an interactive map drawn from the Ancient World Mapping Center and linked to the Getty’s Thesaurus of Geographic Names and Pleiades. Also available are free PDF, EPUB, and MOBI downloads of the book; CSV and JSON downloads of the object data from the catalogue and the accompanying Guide to the Collection; and JPG and PPT downloads of the main catalogue images. © 2016 J. Paul Getty Trust This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042. First edition, 2016 Last updated, December 19, 2017 https://www.github.com/gettypubs/terracottas Published by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 www.getty.edu/publications Ruth Evans Lane, Benedicte Gilman, and Marina Belozerskaya, Project Editors Robin H. Ray and Mary Christian, Copy Editors Antony Shugaar, Translator Elizabeth Chapin Kahn, Production Stephanie Grimes, Digital Researcher Eric Gardner, Designer & Developer Greg Albers, Project Manager Distributed in the United States and Canada by the University of Chicago Press Distributed outside the United States and Canada by Yale University Press, London Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: J. -

Downloaded from the NOA GNSS Network Website (

remote sensing Article Spatio-Temporal Assessment of Land Deformation as a Factor Contributing to Relative Sea Level Rise in Coastal Urban and Natural Protected Areas Using Multi-Source Earth Observation Data Panagiotis Elias 1 , George Benekos 2, Theodora Perrou 2,* and Issaak Parcharidis 2 1 Institute for Astronomy, Astrophysics, Space Applications and Remote Sensing (IAASARS), National Observatory of Athens, GR-15236 Penteli, Greece; [email protected] 2 Department of Geography, Harokopio University of Athens, GR-17676 Kallithea, Greece; [email protected] (G.B.); [email protected] (I.P.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 6 June 2020; Accepted: 13 July 2020; Published: 17 July 2020 Abstract: The rise in sea level is expected to considerably aggravate the impact of coastal hazards in the coming years. Low-lying coastal urban centers, populated deltas, and coastal protected areas are key societal hotspots of coastal vulnerability in terms of relative sea level change. Land deformation on a local scale can significantly affect estimations, so it is necessary to understand the rhythm and spatial distribution of potential land subsidence/uplift in coastal areas. The present study deals with the determination of the relative vertical rates of the land deformation and the sea-surface height by using multi-source Earth observation—synthetic aperture radar (SAR), global navigation satellite system (GNSS), tide gauge, and altimetry data. To this end, the multi-temporal SAR interferometry (MT-InSAR) technique was used in order to exploit the most recent Copernicus Sentinel-1 data. The products were set to a reference frame by using GNSS measurements and were combined with a re-analysis model assimilating satellite altimetry data, obtained by the Copernicus Marine Service. -

Final Report on the Analysis of Charred Plant Remains from the Late Neolithic and Bronze Age Riverside Site of Longas Elatis in Western Macedonia, Northern Greece

IWGP 2016 Paris : International Work-Group for Palaeoethnobotany 2016, 4-9 Jul 2016 Paris (France) Final report on the analysis of charred plant remains from the Late Neolithic and Bronze Age riverside site of Longas Elatis in western Macedonia, northern Greece. Dimitra Kotsachristou1, 2 1Ephorate of Antiquities of Kozani, General Secretariat of Culture, Greece 2Archaeological museum of Aiani, Kozani, Greece INTRODUCTION e-mail: [email protected] Over the last 25 years archaeobotanical sampling in western Macedonia and particularly in the region of Kozani has been intensive and systematic and the archaeobotanical material from several sites are under study or have been published (Kremasti Koiladas, Karathanou and Valamoti 2011, Karathanou et al. 2011, Kleitos, Stylianakou and Valamoti 2012, Phyllotsairi, Mavropigi, Valamoti 2011). This poster presents the final results of analysis of charred plant remains from the Late Neolithic and Bronze Age riverside settlement of Longas Elatis, adding significantly to the already known archaeobotanical material from investigated sites in western Macedonia. THE SITE UNDER STUDY The site is located in the low right bank of Aliakmon, the longest river entirely within Greek boarders (297km up to the point where it flows into the Thermaic Gulf, located immediately south of Thessaloniki regional unit) and particularly in the mild sloping terraces of adjacent hills, covering an area of 3000 m2 (fig. 1, 2). Additionally, it constituted a pole of attraction for people for permanent establishment from the Neolithic period and its use was not abandoned over time while ensured fertile and easily cultivable ground (Karamitrou-Mentesidi 2009, 2011). In the valleys and plains of the Aliakmon a number of important settlements, such as Longas, grew up as long ago as prehistoric times and went on to develop into important cities of the historical era (Karamitrou-Mentesidi and Theodorou 2009, Karamitrou-Mentesidi 2010).