Steinbach, Manitoba: a Community in Search of Place Through the Recovery of Ifs Formative Creeks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

File No. CI 19-01-23329 the QUEEN's BENCH Winnipeg Centre

File No. CI 19-01-23329 THE QUEEN’S BENCH Winnipeg Centre IN THE MATTER OF: The Appointment of a Receiver pursuant to Section 243 of the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act , R.S.C. 1985 c. B-3, as amended and Section 55 of The Court of Queen’s Bench Act , C.C.S.M. c. C280 BETWEEN: ROYAL BANK OF CANADA, Plaintiff, - and - 6382330 MANITOBA LTD., PGRP PROPERTIES INC., and 6472240 MANITOBA LTD. Defendants . SERVICE LIST AS AT May 15, 2020 FILLMORE RILEY LLP Barristers, Solicitors & Trademark Agents 1700 - 360 Main Street Winnipeg, Manitoba R3C 3Z3 Telephone: 204-957-8319 Facsimile: 204-954-0319 J. MICHAEL J. DOW File No. 180007-848/JMD FRDOCS_10130082.1 File No. CI 19-01-23329 THE QUEEN’S BENCH Winnipeg Centre IN THE MATTER OF: The Appointment of a Receiver pursuant to Section 243 of the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act , R.S.C. 1985 c. B-3, as amended and Section 55 of The Court of Queen’s Bench Act , C.C.S.M. c. C280 BETWEEN: ROYAL BANK OF CANADA, Plaintiff, - and - 6382330 MANITOBA LTD., PGRP PROPERTIES INC., and 6472240 MANITOBA LTD. Defendants . SERVICE LIST Party/Counsel Telephone Email Party Representative FILLMORE RILEY LLP 204-957-8319 [email protected] Counsel for Royal 1700-360 Main Street Bank of Canada Winnipeg, Manitoba R3C 3Z3 J. MICHAEL J. DOW Facsimile: 204-954-0319 DELOITTE 204-944-3611 [email protected] Receiver RESTRUCTURING INC. 2300-360 Main Street Winnipeg, Manitoba R3C 3Z3 BRENT WARGA Facsimile: 204-947-2689 JOHN FRITZ 204-944-3586 [email protected] Facsimile 204-947-2689 THOMPSON DORFMAN 204-934-2378 [email protected] Counsel for the SWEATMAN LLP Receiver 1700-242 Hargrave Street Winnipeg, Manitoba R3C 0V1 ROSS A. -

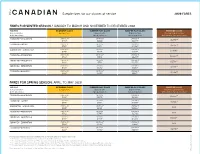

Sample Fares for Our Classes of Service 2020 FARES

Sample fares for our classes of service 2020 FARES FARES FOR WINTER SEASON / JANUARY TO MARCH AND NOVEMBER TO DECEMBER 2020 ROUTES ECONOMY CLASS SLEEPER PLUS CLASS SLEEPER PLUS CLASS PRESTIGE CLASS Fares valid for Escape fare Upper berth, Cabin for two, Prestige cabin for two both directions fare per person fare per person with shower, fare per person — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT TORONTO VANCOUVER $4,981††† $466* $1,111† $1,878†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT TORONTO JASPER $3,753††† $385* $831† $1,406†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT EDMONTON VANCOUVER $2,020††† $190* $574† $969†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT TORONTO EDMONTON $3,366††† $342* $751† $1,267†† STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT WINNIPEG—VANCOUVER ††† † $3,366 $292* $754 $1,273†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT WINNIPEG EDMONTON $2,201††† $158* $494† $835†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT TORONTO WINNIPEG $2,783††† $229* $615† $1043†† FARES FOR SPRING SEASON: APRIL TO MAY 2020 ROUTES ECONOMY CLASS SLEEPER PLUS CLASS SLEEPER PLUS CLASS PRESTIGE CLASS Fares valid for Escape fare Upper berth, Cabin for two, Prestige cabin for two both directions fare per person fare per person with shower, fare per person — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT TORONTO VANCOUVER $5,336††† $466* $1,176† $1,988†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT TORONTO JASPER $4,021††† $385* $881† $1,488†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT EDMONTON VANCOUVER N/A $190* $608† $1,026†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT TORONTO EDMONTON N/A $342* $795† $1,342†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT WINNIPEG VANCOUVER $3,607††† $292* $798† $1,349†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT WINNIPEG EDMONTON N/A $158* $523† $884†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT TORONTO WINNIPEG $2,981††† $229* $651† $1,104†† Prestige class between Vancouver and Edmonton is offered in summer on trains 3 and 4 only. -

COMMUNITY CONSERVATION PLAN Southwestern Manitoba Mixed

Southwestern Manitoba Mixed-grass Prairie IBA Page 1 of 1 COMMUNITY CONSERVATION PLAN for the Southwestern Manitoba Mixed-grass Prairie IMPORTANT BIRD AREA A Grassland Bird Initiative for Southwestern Manitoba's - • Poverty Plains • Lyleton-Pierson Prairies • Souris River Lowlands Prepared by: Cory Lindgren, Ken De Smet Manitoba IBA Program Species At Risk Biologist Oak Hammock Marsh Wildlife Branch, Manitoba Conservation Box 1160, Stonewall, Manitoba R0E 2Z0 200 Saulteaux Crescent, Winnipeg R3J 3W3 Manitoba IBA Program 10/03/01 _____________________________________________________________________________________ Southwestern Manitoba Mixed-grass Prairie IBA Page 2 of 2 Table of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 8 1.1 The Poverty Plains.......................................................................................................................... 8 1.2 Souris River Lowlands ................................................................................................................... 8 1.3 Lyleton-Pierson Prairies ................................................................................................................ 9 2.0 THE IBA PROGRAM........................................................................................................................... 9 2.1 IBA Manitoba ........................................................................................................................... -

Streaming-Live!* Ottawa Senators Vs Winnipeg Jets Live Free @4KHD 23 January 2021

*!streaming-live!* Ottawa Senators vs Winnipeg Jets Live Free @4KHD 23 January 2021 CLICK HERE TO WATCH LIVE FREE NHL 2021 Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Starting XI Live Video result for Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live 120 Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live Stream HD Notre Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Video result for Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live 4231 Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators PreMatch Build Up Ft James Video result for Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live WATCH ONLINE Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live Online Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live NHL Ice Hockey League 2021, Live Streams Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live op tv Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live Reddit Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live 2021, Hockey 2021, Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live 23rd January 2021, Broadcast Tohou USTV Live op tv Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Free On Tv Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live score Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live Update Score Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live on radio 2021, Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live Start Time Tohou Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live Stream NHL Wedneshour,20th 247sports › board › Hockey-102607 › contents 1 hour ago — The Vancouver Canucks are 1-6-2 in their last nine games against the Montreal Arizona Coyotes the Vegas Golden Knights will try to snap out of their current threeLiVe'StrEAM)$* -

Valid Operating Permits

Valid Petroleum Storage Permits (as of September 15, 2021) Permit Type of Business Name City/Municipality Region Number Facility 20525 WOODLANDS SHELL UST Woodlands Interlake 20532 TRAPPERS DOMO UST Alexander Eastern 55141 TRAPPERS DOMO AST Alexander Eastern 20534 LE DEPANNEUR UST La Broquerie Eastern 63370 LE DEPANNEUR AST La Broquerie Eastern 20539 ESSO - THE PAS UST The Pas Northwest 20540 VALLEYVIEW CO-OP - VIRDEN UST Virden Western 20542 VALLEYVIEW CO-OP - VIRDEN AST Virden Western 20545 RAMERS CARWASH AND GAS UST Beausejour Eastern 20547 CLEARVIEW CO-OP - LA BROQUERIE GAS BAR UST La Broquerie Red River 20551 FEHRWAY FEEDS AST Ridgeville Red River 20554 DOAK'S PETROLEUM - The Pas AST Gillam Northeast 20556 NINETTE GAS SERVICE UST Ninette Western 20561 RW CONSUMER PRODUCTS AST Winnipeg Red River 20562 BORLAND CONSTRUCTION INC AST Winnipeg Red River 29143 BORLAND CONSTRUCTION INC AST Winnipeg Red River 42388 BORLAND CONSTRUCTION INC JST Winnipeg Red River 42390 BORLAND CONSTRUCTION INC JST Winnipeg Red River 20563 MISERICORDIA HEALTH CENTRE AST Winnipeg Red River 20564 SUN VALLEY CO-OP - 179 CARON ST UST St. Jean Baptiste Red River 20566 BOUNDARY CONSUMERS CO-OP - DELORAINE AST Deloraine Western 20570 LUNDAR CHICKEN CHEF & ESSO UST Lundar Interlake 20571 HIGHWAY 17 SERVICE UST Armstrong Interlake 20573 HILL-TOP GROCETERIA & GAS UST Elphinstone Western 20584 VIKING LODGE AST Cranberry Portage Northwest 20589 CITY OF BRANDON AST Brandon Western 1 Valid Petroleum Storage Permits (as of September 15, 2021) Permit Type of Business Name City/Municipality -

ROYAL PLAINS Join Walmart at Prominent Location in West Portage La Prairie 2352 Sissons Drive, Portage La Prairie, Manitoba

ROYAL PLAINS Join Walmart at Prominent Location in West Portage la Prairie 2352 Sissons Drive, Portage la Prairie, Manitoba Accommodate all sizes and uses Strong & Growing retail node Up to 150,000 sq. ft. in future Anchored by Walmart Supercentre development available with many national/regional tenants Excellent Access & Exposure Strong local economy Located on the Trans-Canada Investment is booming in housing Highway with 26,448 vehicles daily and agricultural development www.shindico.com ROYAL PLAINS 2352 Sissons Drive, Portage la Prairie, Manitoba PORTAGE LA PRAIRIE - CITY OF POSSIBILITIES Portage la Prairie is a major service centre for the Central Plains region. Centrally located between two major cities (Winnipeg and Brandon) the city enjoys unparalleled access by rail, road and air to all markets across the Canada. Strategically situated in the centre of the continent astride major east-west transportation routes. Portage la Prairie is only forty-five minutes west of Winnipeg, one hour north of the international border, and one hour east of Brandon. Located within the heart of the richest agricultural belt in Manitoba, agriculture and agri-food related processing and services are the major industrial focus of the area with some of the most productive farmland in Canada. • French fry processor J. R. Simplot Company is investing $460 million to more than double production in Portage la Prairie, creating more than 100 new jobs • French-based Roquette has begun construction on a new $400 million pea processing plant in Portage la Prairie. It will be the largest plant of its kind in the world and one of the largest private-sector investments in the history of Manitoba. -

Preservings Chortitzer Diaries -- Dr

-being the Newsletter/Magazine of the Hanover Steinbach Historical Society Inc. Price $10.00 No. 12, June, 1998 “A people who have not the pride to record their history will not long have the virtues to make their history worth recording; and no people who are indifferent to their past need hope to make their future great.” - Jan Gleysteen Chortitzer Diaries of the East Reserve 1874-1930 By Dr. Royden K. Loewen, Chair of Mennonites Studies, University of Winnipeg, Winnipeg, Manitoba, presented to the Annual General Meeting of the Hanover Steinbach Historical Society Inc, Vollwerk (Mitchell), Manitoba, January 17,1998. Introduction: by Old Mennonites in Ontario, written in English, The study of Mennonite diaries is a new way and kept by teenagers and the elderly, by men and Inside This Issue of looking at history. The fact is that many readers by women, by preachers, merchants and farmers. of Mennonite history have until recently been It is a similar case in Manitoba: there are diaries by Feature story, unaware of their existence. I am reminded of one the Kleine Gemeinde at Morris, by the Old Colo- Chortitzer Diaries .......... 1-5 local Mennonite history book that was essentially nists of the West Reserve, by the Bergthalers, later a compendium of pictures since World War II; a known as the Chortitzers, of the East Reserve. President’s Report ................ 6 brief introduction noted that the pioneers had been Fortunately the children and grandchildren of the Editorial ...........................7-15 too busy building farms on the frontier to do any pioneers here have treasured and preserved these Letters ...........................16-22 writing and therefore virtually nothing was known writings. -

Rural Municipality of La Broquerie Meeting Minutes Regular Meeting of Council September 28, 2016 - 6:30 PM

Page 1 of 13 Rural Municipality of La Broquerie Meeting Minutes Regular Meeting of Council September 28, 2016 - 6:30 PM Present: Reeve Weiss, Councillors Peters, Derksen, Chabot, Normandeau, Tétrault, CAO Anne Burns. Absent: Deputy Reeve Unger. 1. MEETING CALLED TO ORDER With a quorum present Reeve Lewis Weiss called the meeting to order at 6:30 PM. 2. ADOPTION OF COUNCIL MEETING AGENDA Resolution No: 2016-472 Moved By: Ivan Normandeau Seconded By: Cameron Peters BE IT RESOLVED THAT the agenda for the regular meeting of September 28, 2016 be accepted with the following additions: 1. Supplemental and cancellation taxes for 2015 and 2016 CARRIED 3. ADOPTION OF PREVIOUS COUNCIL MINUTES Resolution No: 2016-473 Moved By: Wilfred Chabot Seconded By: Alvin Derksen BE IT RESOLVED THAT the minutes of the regular meeting of September 14, 2016 be accepted as presented. CARRIED 4. COUNCIL / COMMITEE / STAFF REPORTS 4.1 Reeve Lewis Weiss Reeve Weiss reported on his attendance at a lunch meeting with Steinbach Mayor Goertzen, CAO Troy Warkentin and CAO Anne Burns on September 20, 2016, fundraiser with MLA Dennis Smook in Vita on September 22, 2016, Pre construction meeting and Public Works/Finance Committee meeting on September 26, 2016 and Round table meeting with Municipal Minister at Mennonite Heritage Village on September 27, 2016. 4.2 Deputy Reeve Darrell Unger Absent. 4.3 Councillor Alvin Derksen Councillor Derksen reported on his attendance at the Arena Board Meeting on September 19, 2016, Finance/Public Works Meeting on September 26, 2016, Round table meeting with Municipal Minister at Mennonite Heritage Village on September 27, 2016. -

Leconte's Sparrow Breeding in Michigan and South Dakota

Vol.lOa7 54]I WALKINSt/AW,Leconte's S2arrow Breeding inMichigan 309 LECONTE'S SPARROW BREEDING IN MICHIGAN AND SOUTH DAKOTA BY LAWRENCE H. WAL•SHXW Plates 21, 22 LXTItXMfirst describedLeconte's Sparrow (Passerherbulus caudacutus) from the interior of Georgiain 1790 (1). On May 24, 1843, Audubon(2) collecteda specimenalong the upper Missouri,but it was nearly thirty years before another specimenwas taken (in 1872) by Dr. Linceceumin WashingtonCounty, Texas (3). The followingyear, 1873, Dr. Coues(4) took five specimenson August9, betweenthe Turtle Mountainsand the Mouseor SourisRiver in. North Dakota, and a sixth on September9, at Long CoteauRiver, North Dakota. Sincethat time many ornithologists havecovered the favoritehabitat of the species,and its breedingrange and winter distributionhave been gradually discovered. The A. O. U. Check-listof 1886gave the rangeas "From the plainseast- ward to Illinois, So. Carolina, and Florida, and from Manitoba south to Texas" (5). The 1931Check-llst (6) states:"Breeds in the Canadianand Transitionzones from Great Slave Lake, Mackenzie,southern Saskatche- wan, and Manitoba southward to North Dakota and southern Minnesota. Winters from southernKansas, southern Missouri, and westernTennessee to Texas, Florida, and the coastof South Carolina, and occasionallyto North Carolina. Casualin Ontario, Illinois and New York; accidentalin Idaho, Utah and Colorado." In Canadathe specieshas beenfound breeding in the easternpart of Alberta(7, 8, 9, 10). I foundit onJune 17, 1936,along the western shores of Buffalo Lake only a few miles from Bashawin central Alberta. On a visit to this areaon June20, an undoubtednest of the specieswas found, but heavy rains, which precededthese visits, had floodedthe entire area and destroyedall of the groundnests in the region. -

Municipal Officials Directory 2021

MANITOBA MUNICIPAL RELATIONS Municipal Officials Directory 21 Last updated: September 23, 2021 Email updates: [email protected] MINISTER OF MUNICIPAL RELATIONS Room 317 Legislative Building Winnipeg, Manitoba CANADA R3C 0V8 ,DPSOHDVHGWRSUHVHQWWKHXSGDWHGRQOLQHGRZQORDGDEOH0XQLFLSDO2IILFLDOV'LUHFWRU\7KLV IRUPDWSURYLGHVDOOXVHUVZLWKFRQWLQXDOO\XSGDWHGDFFXUDWHDQGUHOLDEOHLQIRUPDWLRQ$FRS\ FDQEHGRZQORDGHGIURPWKH3URYLQFH¶VZHEVLWHDWWKHIROORZLQJDGGUHVV KWWSZZZJRYPEFDLDFRQWDFWXVSXEVPRGSGI 7KH0XQLFLSDO2IILFLDOV'LUHFWRU\FRQWDLQVFRPSUHKHQVLYHFRQWDFWLQIRUPDWLRQIRUDOORI 0DQLWRED¶VPXQLFLSDOLWLHV,WSURYLGHVQDPHVRIDOOFRXQFLOPHPEHUVDQGFKLHI DGPLQLVWUDWLYHRIILFHUVWKHVFKHGXOHRIUHJXODUFRXQFLOPHHWLQJVDQGSRSXODWLRQV,WDOVR SURYLGHVWKHQDPHVDQGFRQWDFWLQIRUPDWLRQRIPXQLFLSDORUJDQL]DWLRQV0DQLWRED([HFXWLYH &RXQFLO0HPEHUVDQG0HPEHUVRIWKH/HJLVODWLYH$VVHPEO\RIILFLDOVRI0DQLWRED0XQLFLSDO 5HODWLRQVDQGRWKHUNH\SURYLQFLDOGHSDUWPHQWV ,HQFRXUDJH\RXWRFRQWDFWSURYLQFLDORIILFLDOVLI\RXKDYHDQ\TXHVWLRQVRUUHTXLUH LQIRUPDWLRQDERXWSURYLQFLDOSURJUDPVDQGVHUYLFHV ,ORRNIRUZDUGWRZRUNLQJLQSDUWQHUVKLSZLWKDOOPXQLFLSDOFRXQFLOVDQGPXQLFLSDO RUJDQL]DWLRQVDVZHZRUNWRJHWKHUWREXLOGVWURQJYLEUDQWDQGSURVSHURXVFRPPXQLWLHV DFURVV0DQLWRED +RQRXUDEOHDerek Johnson 0LQLVWHU TABLE OF CONTENTS MANITOBA EXECUTIVE COUNCIL IN ORDER OF PRECEDENCE ............................. 2 PROVINCE OF MANITOBA – DEPUTY MINISTERS ..................................................... 5 MEMBERS OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY ............................................................ 7 MUNICIPAL RELATIONS .............................................................................................. -

Intervention and Resistance: Two Mennonite Visions Conflict in Mexico

Intervention and Resistance: Two Mennonite Visions Conflict in Mexico David M. Quiring, University of Saskatchewan To casual onlookers, the Mennonite world presents a bewildering array of factions, all of whom claim to follow in the tradition of Menno Simons and other early Anabaptists. Although seemingly motivated by sincere desires to discern and follow the will of God, spiritual leaders often have failed to agree on theological issues. As a result, they have led their adherents into separate spiritual enclaves. While some have remained in close physical proximity to the larger society, others have gone to the extreme of seeking geographic isolation. One group that has sought to live secluded from the rest of the world is the Old Colony Church in Mexico. But other Mennonites have not respected that desire for separation. In the past decades, various Mennonite groups have waged what resembles an undeclared war against the Old Co1on:y Mennonite Church in Mexico. Although the rhetoric often resembles that of a war, fortunately both sides ascribe to pacifism and have r~estrictedtheir tactics to non-violent methods of attack and defence. When this research project into the Mexican Mennonites began in the mid-1990s, like many average Canadians and Americans of 84 Journal ofMennonite Studies Mennonite descent, I lacked awareness of the conflict between the Mennonite groups in Mexico. My initial interest in the Mennonites of Latin America, and particularly the Old Colonists, derived from several sources. While curiosity about these obviously quaint people provided reason enough for exploring their history, a mare personal motivation also existed. The Old Colonists and my family share a common ancestry. -

Serving Steinbach & Area for Over 20 Years! Grand

Section B Thursday, November 28, 2013 www.thecarillon.com CarillonThe Classifieds PROFESSIONAL SERVICES • PROPERTY • EMPLOYMENT • MISCELLANEOUS DIRECTORY OF SERVICES KIM MIREAULT, TPI Travel Designer For all your renovation needs, call Gilbert J. Landreville Roger 204-355-7572 Kelvin 204-392-2246 MANITOBA LAND SURVEYOR From T-bar celings to Residential to Agriculture 8*3 406 Main St. STEINBACH 204-326-2117 E2 495 Hwy 12 N 204.990.1140 See us for !! GUNS !! [email protected] Sales - Service - Parts all your Handguns - Rifles - Shotguns iwannatravel.ca Self Storage Ile des Chenes, Mb. New & Used CFSC/CRFSC - Firearms Courses KIM MIREAULT - 500 sq ft spaces - heatable Freightliner Manitoba Hunter Safety Courses Courses held monthly in Niverville | All Skill Levels - 7x10 overhead doors truck needs. www.ManitobaSportsmen.com - separate man door Ph 204-388-9037 between 7 am and 8 pm – Now is the time to - lighting & plugs service your quads 2 miles north of Steinbach 204-326-2600 AUTO off Hwy 12 and sleds! www.trucksunlimitedinc.com E-2 Ben R SALES 204-346-2457 2010 Honda CRV AWD Come see Korey, the best service tec. Only USED AND CONSIGNMENT in the industry! Please join us for our 34000 kms Annual Food and Toy EQUIPMENT SALES RIKSID Drive Friday Nov. 29th. C ent. ltd. E 204-326-3431 Bring a new toy or $ SALE 1½ MILES EAST ON CLEAR SPRINGS RD. non-perishable 19,995! food item and receive Robert Warkentin 45 Hwy 12 N, Steinbach a free adjustment!! CELL: www.benrauto.com 204-326-2220 Lots of goodies too! 204-371-0285 Let’s Go Personal 204-326-3400 Caring Growing Loewen Chiropractic Clinic Higher! Encouragement BUSINESS: Xrays on site.