Do Price Resets Work?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neumann College News

Neumann University News One Neumann Drive, Aston, PA 19014-1298 For Immediate Release – October 24, 2018 Contact: Stephen Bell 610-558-5549 AFCU Appoints Executive Director for Mission The Association of Franciscan Colleges and Universities (AFCU) has appointed Debi Haug as its executive director for mission. She will be based at Neumann University (Aston, Pennsylvania), one of 24 colleges that are members of the organization. Haug has 18 years of experience in Catholic ministry, including campus minister at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Oregon; campus minister and wedding coordinator at Saint Mary's College, Notre Dame; campus minister for Winthrop University, Rock Hill, South Carolina; and campus minister at Ball State University Newman Center and University Parish at Ball State University, Muncie, Indiana; She has also served at parishes in Portland, Oregon and South Bend, Indiana. After graduating with a BA in Pastoral Leadership from Marian University, a Franciscan institution in Indianapolis, Indiana, Haug served as a youth minister for the Jesuit Retreat Program in Milford, Ohio. Her post-graduate education includes courses in Theological Studies at St. Meinrad School of Theology in Indiana and current matriculation in a Certificate in Franciscan Studies at the University of St. Francis in Joliet, Illinois. Her roots in Franciscan education extend back to elementary school, where she was taught by the Sisters of St. Francis of Perpetual Adoration, the same congregation that now leads the University of St. Francis in Fort Wayne, Indiana. “I feel honored to have been chosen,” says Haug, “and am eager to collaborate with the Board of the AFCU to enhance the mission effectiveness of the organization and its member colleges and universities.” The executive director for mission works with the AFCU leadership to set mission- related priorities for the organization and offer services that will support mission programs to member institutions. -

Edward J. Rushton MFA Curriculum Vitae Home Address 314 Rogers Rd. Statesboro, GA 30458 (912) 531-8019(Cell Phone) Work Address

Edward J. Rushton MFA Curriculum Vitae Address Home Address Work Address 314 Rogers Rd. Georgia Southern University Statesboro, GA 30458 Betty Foy Sanders Department of Art (912) 531-8019(cell phone) 224 Pitman Drive, Office 2022 P.O. Box 8032 Statesboro, GA 30460-8032 (912) 478-5283 e-mail [email protected] Education 1994 MFA The University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA. 1993 MA The University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA. 1989 BA Psychology/ Art (Double Major) The University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA. Professional Appointments Associate Professor Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, Georgia, August 2008 to present Courses Taught: ART 2010 Two Dimensional Design. An introduction to the elements of design and the principles by which they are organized to create effective visual statements. ART 2233, Computer Graphics. Introductory overview of computer-based imaging. Students will use industry software, Adobe Photoshop, Illustrator and Indesign to create and manipulate digital images and page layouts. ART 2331, Visual Thinking in Graphic Design. An introduction to graphic design principles. The focus on student’s development of creative vision toward effective visual communication. ART 2330, Typography 1. Introduction to Typography. A formal introduction to the fundamental principles of both the purity and precision of typographical material, it’s logical and disciplined structure, while using type as a stand alone design element. ART 3330 New Media Design, a study of the various aspects of new media design, specifically how formal aesthetic and concept is integrated with motion, sequence, duration, time and sound. Visual solutions will take shape in a non-print format that investigates how a user experiences new media differently than traditional media. -

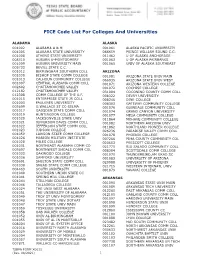

FICE Code List for Colleges and Universities (X0011)

FICE Code List For Colleges And Universities ALABAMA ALASKA 001002 ALABAMA A & M 001061 ALASKA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY 001005 ALABAMA STATE UNIVERSITY 066659 PRINCE WILLIAM SOUND C.C. 001008 ATHENS STATE UNIVERSITY 011462 U OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE 008310 AUBURN U-MONTGOMERY 001063 U OF ALASKA FAIRBANKS 001009 AUBURN UNIVERSITY MAIN 001065 UNIV OF ALASKA SOUTHEAST 005733 BEVILL STATE C.C. 001012 BIRMINGHAM SOUTHERN COLL ARIZONA 001030 BISHOP STATE COMM COLLEGE 001081 ARIZONA STATE UNIV MAIN 001013 CALHOUN COMMUNITY COLLEGE 066935 ARIZONA STATE UNIV WEST 001007 CENTRAL ALABAMA COMM COLL 001071 ARIZONA WESTERN COLLEGE 002602 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 001072 COCHISE COLLEGE 012182 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 031004 COCONINO COUNTY COMM COLL 012308 COMM COLLEGE OF THE A.F. 008322 DEVRY UNIVERSITY 001015 ENTERPRISE STATE JR COLL 008246 DINE COLLEGE 001003 FAULKNER UNIVERSITY 008303 GATEWAY COMMUNITY COLLEGE 005699 G.WALLACE ST CC-SELMA 001076 GLENDALE COMMUNITY COLL 001017 GADSDEN STATE COMM COLL 001074 GRAND CANYON UNIVERSITY 001019 HUNTINGDON COLLEGE 001077 MESA COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001020 JACKSONVILLE STATE UNIV 011864 MOHAVE COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001021 JEFFERSON DAVIS COMM COLL 001082 NORTHERN ARIZONA UNIV 001022 JEFFERSON STATE COMM COLL 011862 NORTHLAND PIONEER COLLEGE 001023 JUDSON COLLEGE 026236 PARADISE VALLEY COMM COLL 001059 LAWSON STATE COMM COLLEGE 001078 PHOENIX COLLEGE 001026 MARION MILITARY INSTITUTE 007266 PIMA COUNTY COMMUNITY COL 001028 MILES COLLEGE 020653 PRESCOTT COLLEGE 001031 NORTHEAST ALABAMA COMM CO 021775 RIO SALADO COMMUNITY COLL 005697 NORTHWEST -

2018–2019 Undergraduate Catalog

UNDERGRADUATE CATALOG 2018–2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS General Information 1 Admission 3 Tuition and Fees 7 Financial Aid 7 Student Life 8 Academic Services 9 Academic Regulations and Policies 10 Core Curriculum 29 Degree Requirements and Graduation 32 Associate Degree Program 35 Bachelor Degree Programs 36 Other Undergraduate Academic Programs 93 Course Descriptions 99 Directory 222 Academic Calendar 233 Index 234 Viterbo University is accredited by the Higher Learning Commission (hlcommission.org), a regional accreditation agency recognized by the U.S. Department of Education. 230 South LaSalle Street, Suite 7-500, Chicago, Illinois 60604-1411, 800- 621-7440; 312-263-0456; [email protected]. Viterbo University is recognized and approved by the Iowa College Student Aid Commission to offer degree programs in education. Viterbo University is registered as a private institution with the Minnesota Office of Higher Education pursuant to Minnesota Statues, sections 136A.61 to 136A.71. Registration is not an endorsement of the institution. Credits earned at the institution may not transfer to all other institutions. It is the policy of Viterbo University not to discriminate against students, applicants for admission, or employees on the basis of sex, race, color, religion, national origin, ancestry, age, sexual orientation, or physical or mental disabilities unrelated to institutional jobs, programs, or activities. Viterbo University is a Title IX institution. This catalog does not establish a contractual relationship. Its purpose is to provide students with information regarding programs, requirements, policies, and procedures to qualify for a degree from Viterbo University. Viterbo University reserves the right, through university policy and procedure, to make necessary changes to curriculum and programs as educational and financial considerations may require. -

CTS 2013—Page 2

Teaching Theology and Handing on the Faith: Challenges and Convergences Fifty-Ninth Annual Convention in conjunction with The National Association of Baptist Professors of Religion (NABPR) Creighton University Omaha, Nebraska Thursday, May 30th – Sunday, June 2nd, 2013 CTS 2013—Page 2 CTS 2013—Page 3 Wednesday, May 29th 1:00-5:00 Board of Directors’ Meeting Harper 2060 Thursday, May 30th 12:00-5:00 Convention Registration and Residence Hall Check-In Kiewit Hall Lobby 9:30-5:00 Board of Directors’ Meeting Harper 2060 4:30-5:30 Women’s Caucus Harper 3029 6:00-7:00 Dinner Brandeis Dining Hall 7:30-9:00 Welcome Harper Auditorium Sandra Yocum University of Dayton (Ohio) President, College Theology Society Presiding Gail S. Risch Dennis Hamm, SJ Creighton University (Nebraska) Local Coordinators Father Timothy Lannon, SJ President, Creighton University Bridget M. Keegan, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, Creighton University Plenary Address William Portier, University of Dayton (Ohio) Moderator The Heart Has Its Reasons: Giving an Account of the Hope That Is In Us Father Robert Imbelli Boston College (Massachusetts) CTS 2013—Page 4 Thursday, May 30th 9:00-11:00 Reception Harper Center Generously hosted by the Office of the President, Creighton University Ballroom, 4th Floor Friday May 31st 7:30-8:45 Breakfast Brandeis Dining Hall 9:00 -5:00 Exhibits Open—Publishers and Organizations of interest to CTS Members Harper 3027 9:00-10:30 Sectional Meetings 1 Harper 2060 Arts, Literature, Media and Religion Mary-Paula Cancienne, RSM, -

Profile- COLLEGES 2017-20

COLLEGE ACCEPTANCES 2017-2020 Bold letters indicate schools enrolling one or members of the Classes of 2017-2020 Albright College Allegheny College American University American University of Paris Amherst College Anderson University Appalachian State University Arizona State University Auburn University Babson College Bates College Baylor University Belmont University Bentley University Biola University Boston College Boston University Bowdoin College Bowling Green State University Brandeis University Bridgewater College Brown University Bryant University Bryn Mawr College Bucknell University Butler University California Institute of Technology California Polytechnic State University Campbell University Carleton College Carnegie Mellon University Carson-Newman University Case Western Reserve University Catawba College Central Piedmont Community College Centre College Champlain College Christopher Newport University The Citadel Claflin University Clark Atlanta University Clemson University Coastal Carolina University College of Charleston College of William and Mary College of Wooster Colorado College Colorado School of Mines Colorado State University Columbia University Connecticut College Cornell University Cornish College of the Arts Dalhousie University Dartmouth College Davidson College Denison University DePaul University DePauw University Dickinson College Drew University Drexel University Duke University Duquesne University Durham University East Carolina University Eckerd College Elon University Embry-Riddle Aeronautical Inst. -

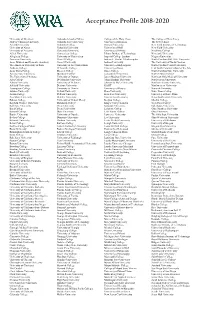

Acceptance Profile 2018-2020

Acceptance Profile 2018-2020 University of Aberdeen Colorado School of Mines College of the Holy Cross The College of New Jersey Abilene Christian University Colorado State University University of Houston The New School Adelphi University Columbia College Howard University New York Institute of Technology University of Akron Columbia University University of Hull New York University University of Alabama Concordia University University of Illinois Newberry College Alfred University Connecticut College Illinois Institute of Technology Newcastle University Allegheny College University of Connecticut Imperial College London Niagara University American University Cornell College Indiana U-Purdue U Indianapolis North Carolina A&T State University Amer Musical and Dramatic Academy Cornell University Indiana University The University of North Carolina The American University of Paris University of the Cumberlands University of Indianapolis North Carolina Central University Amherst College D’Youville College University of Iowa U of North Carolina School of the Arts Anna Maria College Daemen College Ithaca College North Carolina State University Arizona State University Davidson College Jacksonville University North Central College The University of Arizona University of Dayton James Madison University Northeast Ohio Medical University ASA College De Montfort University Johns Hopkins University Northeastern University Asbury University University of Delaware Johnson & Wales University Northern Arizona University Ashland University Denison University -

The Missing Students: Gratitude and Resolve WAICU Leads in Preparing

Newsletter of the Wisconsin Association of Independent Colleges and Universities (WAICU) SUMMER 2013 VOL. 45 NO. 2 INDEPENDENT INSIGHTS The missing students: gratitude and resolve AlvernoAlverno College When I was a kid, I loved the newspaper Wisconsin’s competitive position in the global Bellin College Beloit College feature which laid two drawings side-by-side, “Knowledge Economy.” Beloit College Cardinal Stritch University and the reader was challenged to find the To be precise, it is not students we are Cardinal Stritch University CarrollCarroll University differences between them. Sometimes it was missing; it is opportunity for students. CarthageCarthage College obvious—no sun in the sky, for example— WAICU’s 23 member colleges and universities ColumbiaConcordia College University of Nursing and sometimes the difference was hard to have grown their enrollment by 97 percent ConcordiaEdgewood University College Wisconsin find—a curl of hair. It is a maxim of logic that since 1980. Even though the numbers of LakelandEdgewood CollegeCollege you “cannot prove a negative.” In everyday traditional age students (18 to 22 years old) Lakeland College Lawrence University conversation, we say “you don’t know what are declining, WAICU has for more than LawrenceMarian University University you are missing!” 35 years reached out with flexible degree MarquetteMarian University University Marquette University Milwaukee Institute of Art & Design We are in danger of missing something programs to meet employer needs and to Medical College of Wisconsin Milwaukee School of Engineering else in Wisconsin: students, or, put another provide accessible, affordable opportunities Milwaukee Institute of Art & Design way, the students themselves are missing out for students. -

2022 NAIA Division/Conference Alignments

2022 NAIA Division/Conference Alignments – 64 Announced Programs The following list provides a breakdown of NAIA men's volleyball sponsoring schools by division and conference. CONFERENCES Association of Independents Wolverine-Hoosier Athletic Lincoln College Golden State Athletic Conference Conference Vanguard University Arizona Christian University Aquinas College Benedictine University at Mesa Cornerstone University – New in American Midwest California, University of, Merced 2021 Missouri Baptist University Hope International University Goshen College Park University The Master’s University Indiana Tech St. Louis College of Pharmacy Menlo College Lawrence Technological University Ottawa University Arizona Lourdes University Cal Pac Siena Heights University Saint Katherine University Heart of America Athletic Simpson University Conference Programs adding in 2021 Westcliff University Clarke University Carlow University Culver-Stockton College Central Christian University Chicagoland Collegiate Graceland University Cornerstone University Calumet College of St. Joseph Grand View University Georgetown College Cardinal Stritch University Missouri Valley College Hastings College Judson University Mount Mercy University Olivet Nazarene Olivet Nazarene – New in 2021 William Penn University Roosevelt University Robert Morris University– New in 2021 Programs adding in 2022 Saint Xavier University Kansas Collegiate Athletic Bethel University St. Ambrose University Conference Fisher College Trinity Christian College Kansas Wesleyan (2022) Kansas Wesleyan Viterbo University Ottawa University Saint Mary of the Woods University of Rio Grande Crossroads League Mid-South Bethel University – New in 2022 Bluefield College Programs adding in 2023 Mount Vernon Nazarene Campbellsville University Saint Mary of the Woods Cumberland University Great Plains Athletic Conference Georgetown College – New in Briar Cliff University 2021 Life University Dordt University Hastings College – New in 2021 Midway University Morningside College Reinhardt University University of Jamestown St. -

List of Undocumented/DACA Policies for US Colleges & Universties

Can undoc students purchase Provide Meet full health institutional, finaid need for Undoc treated as Loan-Free insurance from need-based aid eligible non- College Public/Priva Need-Blind for Domestic or Int'l Meet full finaid need FinAid Awards the college/ to undoc citizens (US, App Fee College College City State te Undoc students for undoc? for Undoc univ? students Perm Res)? Waiver Special Population Illinois ACAC Undoc List Undoc Notes California College of the Arts Oakland CA Private N https://www.iacac.org/undocumented/california-college-arts/ California Institute of Technology (CalTech) Oakland CA Private International N Y Chapman University Orange CA Private N https://www.iacac.org/undocumented/chapman-university/ Claremont McKenna College Claremont CA Private Domestic Y N Y Y Dominican University of California San Rafael CA Private N N https://www.iacac.org/undocumented/dominican-university-of-california/ Fresno Pacific University Fresno CA Private International Harvey Mudd College Claremont CA Private International N Y Engineering Mills College Oakland CA Private International N Women Minverva Schools at KGI San Francisco CA Private Y Mount St. Mary's College Los Angeles CA Private International N Occidental College Los Angeles CA Private N International Y N Y Y Pepperdine University Malibu CA Private International N Pitzer College Claremont CA Private Y (1 spot available) N Y https://www.iacac.org/undocumented/pitzer-college/ Pomona College Claremont CA Private Y Domestic Y Y Y Y https://www.iacac.org/undocumented/pomona-college/ -

GR Course Catalog

Viterbo University Graduate Catalog 2020-2021 ________ 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS page General Information 3 Graduate Admission 6 Student Life 8 Financial Aid and Tuition 8 Academic Services 8 Academic Regulations and Policies 9 Graduate Degree Requirements 27 Graduate Programs 29 Course Descriptions 86 Directory 117 Faculty Emeritus 126 Academic Calendar 128 Viterbo University is accredited by the Higher Learning Commission (hlcommission.org), a regional accreditation agency recognized by the U.S. Department of Education. 230 South LaSalle Street, Suite 7-500, Chicago, Illinois 60604-1411, 800-621- 7440; 312-263-0456; [email protected]. Viterbo University is registered with the Iowa College Student Aid Commission to offer programs via face-to-face and distance education delivery to Iowa residents. Viterbo University is registered as a private institution with the Minnesota Office of Higher Education pursuant to Minnesota Statues, sections 136A.61 to 136A.71. Registration is not an endorsement of the institution. Credits earned at the institution may not transfer to all other institutions. It is the policy of Viterbo University not to discriminate against students, applicants for admission, or employees on the basis of sex, race, color, religion, national origin, ancestry, age, sexual orientation, or physical or mental disabilities unrelated to institutional jobs, programs, or activities. Viterbo University is a Title IX institution. This catalog does not establish a contractual relationship. Its purpose is to provide students with information regarding programs, requirements, policies, and procedures to qualify for a degree from Viterbo University. Viterbo University reserves the right, through university policy and procedure, to make necessary changes to curriculum and programs as educational and financial considerations may require. -

GR Course Catalog

Viterbo University Graduate Catalog 2021-2022 ________ 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS page General Information 3 Graduate Admission 6 Student Life 8 Financial Aid and Tuition 8 Academic Services 9 Academic Regulations and Policies 9 Graduate Degree Requirements 27 Graduate Programs 29 Course Descriptions 92 Directory 128 Faculty Emeritus 136 Academic Calendar 139 Viterbo University is accredited by the Higher Learning Commission (hlcommission.org), a regional accreditation agency recognized by the U.S. Department of Education. 230 South LaSalle Street, Suite 7-500, Chicago, Illinois 60604-1411, 800-621- 7440; 312-263-0456; [email protected]. Viterbo University is registered with the Iowa College Student Aid Commission to offer programs via face-to-face and distance education delivery to Iowa residents. Viterbo University is registered as a private institution with the Minnesota Office of Higher Education pursuant to Minnesota Statues, sections 136A.61 to 136A.71. Registration is not an endorsement of the institution. Credits earned at the institution may not transfer to all other institutions. It is the policy of Viterbo University not to discriminate against students, applicants for admission, or employees on the basis of sex, race, color, religion, national origin, ancestry, age, sexual orientation, or physical or mental disabilities unrelated to institutional jobs, programs, or activities. Viterbo University is a Title IX institution. This catalog does not establish a contractual relationship. Its purpose is to provide students with information regarding programs, requirements, policies, and procedures to qualify for a degree from Viterbo University. Viterbo University reserves the right, through university policy and procedure, to make necessary changes to curriculum and programs as educational and financial considerations may require.