Making Streets Safe for Cycling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Training Course Non-Motorised Transport Author

Division 44 Environment and Infrastructure Sector Project „Transport Policy Advice“ Training Course: Non-motorised Transport Training Course on Non-motorised Transport Training Course Non-motorised Transport Author: Walter Hook Findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this document are based on infor- Editor: mation gathered by GTZ and its consultants, Deutsche Gesellschaft für partners, and contributors from reliable Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) GmbH sources. P.O. Box 5180 GTZ does not, however, guarantee the D-65726 Eschborn, Germany accuracy or completeness of information in http://www.gtz.de this document, and cannot be held responsible Division 44 for any errors, omissions or losses which Environment and Infrastructure emerge from its use. Sector Project „Transport Policy Advice“ Commissioned by About the author Bundesministerium für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung (BMZ) Walter Hook received his PhD in Urban Friedrich-Ebert-Allee 40 Planning from Columbia University in 1996. D-53113 Bonn, Germany He has served as the Executive Director of the http://www.bmz.de Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP) since 1994. He has also served Manager: as adjunct faculty at Columbia University’s Manfred Breithaupt Graduate School of Urban Planning. ITDP is a non-governmental organization dedicated to Comments or feedback? encouraging and implementing We would welcome any of your comments or environmentally sustainable transportation suggestions, on any aspect of the Training policies and projects in developing countries. Course, by e-mail to [email protected], or by surface mail to: Additional contributors Manfred Breithaupt This Module also contains chapters and GTZ, Division 44 material from: P.O. Box 5180 Oscar Diaz D-65726 Eschborn Michael King Germany (Nelson\Nygaard Consulting Associates) Cover Photo: Dr. -

Pedestrian and Bicycle Friendly Policies, Practices, and Ordinances

Pedestrian and Bicycle Friendly Policies, Practices, and Ordinances November 2011 i iv . Pedestrian and Bicycle Friendly Policies, Practices, and Ordinances November 2011 i The Delaware Valley Regional Planning The symbol in our logo is Commission is dedicated to uniting the adapted from region’s elected officials, planning the official professionals, and the public with a DVRPC seal and is designed as a common vision of making a great region stylized image of the Delaware Valley. even greater. Shaping the way we live, The outer ring symbolizes the region as a whole while the diagonal bar signifies the work, and play, DVRPC builds Delaware River. The two adjoining consensus on improving transportation, crescents represent the Commonwealth promoting smart growth, protecting the of Pennsylvania and the State of environment, and enhancing the New Jersey. economy. We serve a diverse region of DVRPC is funded by a variety of funding nine counties: Bucks, Chester, Delaware, sources including federal grants from the Montgomery, and Philadelphia in U.S. Department of Transportation’s Pennsylvania; and Burlington, Camden, Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) Gloucester, and Mercer in New Jersey. and Federal Transit Administration (FTA), the Pennsylvania and New Jersey DVRPC is the federally designated departments of transportation, as well Metropolitan Planning Organization for as by DVRPC’s state and local member the Greater Philadelphia Region — governments. The authors, however, are leading the way to a better future. solely responsible for the findings and conclusions herein, which may not represent the official views or policies of the funding agencies. DVRPC fully complies with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and related statutes and regulations in all programs and activities. -

Propelling Change a Guide to Effective Cycling Advocacy Ward Advocacy Program (WAP)

Propelling Change A Guide to Effective Cycling Advocacy Ward Advocacy Program (WAP) The Ward Advocacy Program is at the heart of the bike union. Its goal is to connect individuals who are motivated to improving cycling infrastructure and offering education in their ward. The vision of the program is to build a movement of grassroots advocacy in local wards which will improve cycling for everyone in the city. The Ward Advocacy Program is meant to engage cyclists, and non-cyclists alike, to support activities that promote the everyday use of bicycles by improving infrastructure, facilities and the public perception of cycling as a valid and vital mode of transportation. Toronto Cyclists Union The Toronto Cyclists Union is a membership-based organization that brings together cyclists from all across Toronto. We are a strong, unified voice advocating the rights of cyclists of all ages and from all parts of the city. We aim to shift the political culture that has resisted the changes that are needed to ensure safe streets for cyclists. We are a vibrant and amplified voice calling for the common goals of safe, legitimate and accessible cycling in Toronto. The bike union coordinates city-wide advocacy on behalf of our members and provide resources for cyclists to be effective advocates themselves by participating in the Ward Advocacy Program. Our commitment to you The bike union and ward groups work together in trust and for mutual benefit to improve cycling conditions across the city. We recognize that to realize our vision of a united, cyclist -

Costing of Bicycle Infrastructure and Programs in Canada Project Team

Costing of Bicycle Infrastructure and Programs in Canada Project Team Project Leads: Nancy Smith Lea, The Centre for Active Transportation, Clean Air Partnership Dr. Ray Tomalty, School of Urban Planning, McGill University Researchers: Jiya Benni, The Centre for Active Transportation, Clean Air Partnership Dr. Marvin Macaraig, The Centre for Active Transportation, Clean Air Partnership Julia Malmo-Laycock, School of Urban Planning, McGill University Report Design: Jiya Benni, The Centre for Active Transportation, Clean Air Partnership Cover Photo: Tour de l’ile, Go Bike Montreal Festival, Montreal by Maxime Juneau/APMJ Project Partner: Please cite as: Benni, J., Macaraig, M., Malmo-Laycock, J., Smith Lea, N. & Tomalty, R. (2019). Costing of Bicycle Infrastructure and Programs in Canada. Toronto: Clean Air Partnership. CONTENTS List of Figures 4 List of Tables 7 Executive Summary 8 1. Introduction 12 2. Costs of Bicycle Infrastructure Measures 13 Introduction 14 On-street facilities 16 Intersection & crossing treatments 26 Traffic calming treatments 32 Off-street facilities 39 Accessory & support features 43 3. Costs of Cycling Programs 51 Introduction 52 Training programs 54 Repair & maintenance 58 Events 60 Supports & programs 63 Conclusion 71 References 72 Costing of Bicycle Infrastructure and Programs in Canada 3 LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1: Bollard protected cycle track on Bloor Street, Toronto, ON ..................................................... 16 Figure 2: Adjustable concrete barrier protected cycle track on Sherbrook St, Winnipeg, ON ............ 17 Figure 3: Concrete median protected cycle track on Pandora Ave in Victoria, BC ............................ 18 Figure 4: Pandora Avenue Protected Bicycle Lane Facility Map ............................................................ 19 Figure 5: Floating Bus Stop on Pandora Avenue ........................................................................................ 19 Figure 6: Raised pedestrian crossings on Pandora Avenue ..................................................................... -

The Vermont Legislative Research Shop

The Vermont Legislative Research Shop Healthy Communities Background Many lawmakers and organizations are recognizing the connection between public health and community planning. A 1998 study from the Centers for Disease Control reports that approximately 29% of adults in the US are considered “sedentary” and 50% are considered overweight, creating what some consider a formidable health burden (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1998). Many interest groups and professionals agree that physical inactivity can be remedied in part by healthy city planning, but differ on the best way to implement changes. Healthy Residents There are proactive ideas to help community members become more active, most prominent is the push to include walking and/or bicycling into one’s daily routine (Killingsworth 2001). Walking is perhaps the most accessible form of exercise for all people, and studies suggest that it can be beneficial. For instance, in a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, it is reported that “among retired, nonsmoking men, those who walked less than 1.6 km a day had a mortality rate nearly twice that of those who walked more than 3.2 km per day” (Hakim et al, 1998). Bicycling is another popular form of exercise that can allow people to get school and work every day. The League of American Bicyclists reports that about 42 million Americans own bicycles, but many people use them recreationally rather than as a primary form of transportation (Killingsworth 1998). Killingsworth also reports that “in the United States, nearly 25% of all trips are less than 1 mile, but more than 75% these short trips are made by automobile, so it is reasonable to expect that many trips could be made on foot or bicycle” (1998). -

Approved-Bicycle-Master-Plan-Framework-Report.Pdf

MONTGOMERY COUNTY BICYCLE MASTER PLAN FRAMEWORK abstract This report outlines the proposed framework for the Montgomery County Bicycle Master Plan. It defines a vision by establishing goals and objectives, and recommends realizing that vision by creating a bicycle infrastructure network supported by policies and programs that encourage bicycling. This report proposes a monitoring program designed to make the plan implementation process both clear and responsive. 2 MONTGOMERY COUNTY BICYCLE MASTER PLAN FRAMEWORK contents 4 Introduction 6 Master Plan Purpose 8 Defining the Vision 10 Review of Other Bicycle Plans 13 Vision Statement, Goals, Objectives, Metrics and Data Requirements 14 Goal 1 18 Goal 2 24 Goal 3 26 Goal 4 28 Goals and Objectives Considered but Not Recommended 30 Realizing the Vision 32 Low-Stress Bicycling 36 Infrastructure 36 Bikeways 55 Bicycle Parking 58 Programs 58 Policies 59 Prioritization 59 Bikeway Prioritization 59 Programs and Policies 60 Monitoring the Vision 62 Implementation 63 Accommodating Efficient Bicycling 63 Approach to Phasing Separated Bike Lane Implementation 63 Approach to Implementing On-Road Bicycle Facilities Incrementally 64 Selecting A Bikeway Recommendation 66 Higher Quality Sidepaths 66 Typical Sections for New Bikeway Facility Types 66 Intersection Templates A-1 Appendix A: Detailed Monitoring Report 3 MONTGOMERY COUNTY BICYCLE MASTER PLAN FRAMEWORK On September 10, 2015, the Planning Board approved a Scope of Work for the Bicycle Master Plan. Task 4 of the Scope of Work is the development of a methodology report that outlines the approach to the Bicycle Master Plan and includes a discussion of the issues identified in the Scope of Work. -

Oxfordshire Cycling Design Standards

OXFORDSHIRE CYCLING DESIGN STANDARDS Rail Station School Shops A guide for Developers, Planners and Engineers Summer 2017 OXFORDSHIRE CYCLING DESIGN STANDARDS FOREWORD Oxfordshire County Council aims to make cycling and walking a central part of transport, planning, health and clean air strategies. We are doing this through our Local Transport Plan: Connecting Oxfordshire, Active & Healthy Travel Strategy, Air Quality Strategy and working together with Oxfordshire’s Local Planning Authorities to ensure walking and cycling considerations are designed into masterplans and development designs from the outset. The Council recognises that good highway design, which prioritises and creates dedicated space for cycling and walking, will signifcantly contribute to: - improving people’s health and wellbeing, - improving safety for pedestrians and cyclists, - reducing congestion, - improving air quality, - boosting the local economy, and - creating attractive environments where people wish to live Working together with cycling, walking and physical activity associations and City and District Councils, as well as planning, transport and public health offcers through the Active & Healthy Travel Steering Group, Oxfordshire County Council has produced Design Standards for both cycling and walking respectively. These two documents together convey our vision for better active travel infrastructure in Oxfordshire to support decision makers and set out more clearly what is expected of developers. Research commissioned by British Cycling (2014)1, found that -

Amherst Multimodal Master Plan Utilizing Systematic Safety Principles to Develop a Town-Wide Multimodal Network

Amherst Multimodal Master Plan Utilizing Systematic Safety Principles to Develop a Town-wide Multimodal Network Amherst Bicycle & Pedestrian Advisory Committee Amherst Multimodal Master Plan Multimodal Master Plan Version 9.2.1 June 1, 2019 Amherst Bicycle & Pedestrian Advisory Committee Amherst, New Hampshire Principal Authors Christopher Buchanan and Simon Corson Amherst Bicycle & Pedestrian Advisory Committee Members George Bower Christopher Buchanan, chairman Patrick Daniel, recreation commission ex-officio Richard Katzenberg, vice chair Wesley Robertson, conservation commission ex-officio Judy Shenk Christopher Shenk Alternate Members Mark Bender Jared Hardner, alternate conservation commission ex-officio John Harvey Carolyn Mitchell Wendy Rannenberg, alternate recreation commission ex-officio With the Assistance of Bruce Berry Susan Durling Matthew Waitkins, Senior Transportation Planner, Nashua Regional Planning Commission Page i Amherst Multimodal Master Plan Table of Contents 1 A Town-Wide Multimodal Network ......................................................................................................... 1 1.1 The Amherst Bicycle and Pedestrian Advisory Committee .......................................................... 1 1.2 Purpose ............................................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Plan Outreach & Engagement .......................................................................................................... 1 1.4 -

MINI-ROUNDABOUTS Mini-Roundabouts Or Neighborhood Traffic Circles Are an Ideal Treatment for Minor, Uncontrolled Intersections

MINI-ROUNDABOUTS Mini-roundabouts or neighborhood traffic circles are an ideal treatment for minor, uncontrolled intersections. The roundabout configuration lowers speeds without fully stopping traffic. Check out NACTO’s Urban Street Design Guide or FHWA’s Roundabout: An Information Guide Design Guide for more details. 4 DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS COMMON MATERIALS CATEGORIES 1 2 Mini-roundabouts can be created using raised islands 1 SURFACE TREATMENTS: and simple markings. Landscaping elements are an » Striping: Solid white or yellow lines can be used important component of the roundabout and should in conjunction with barrier element to demarcate be explored even for a short-term demonstration. the roundabout space. Other likely uses include crosswalk markings: solid lines to delineate cross- The roundabout should be designed with careful walk space and / or zebra striping. consideration to lane width and turning radius for vehicles. A mini-roundabout on a residential » Pavement Markings: May include shared lane markings to guide bicyclists through the street should provide approximately 15 ft. of 2 clearance from the corner to the widest point on intersection and reinforce rights of use for people the circle. Crosswalks should be used to indicate biking. (Not shown) where pedestrians should cross in advance of the » Colored treatments: Colored pavement or oth- roundabout. Shared lane markings (sharrows) should er specialized surface treatments can be used to be used to guide people on bikes through the further define the roundabout space (not shown). intersections, in conjunction with bicycle wayfinding 2 BARRIER ELEMENTS: Physical barriers (such as route markings if appropriate. delineators or curbing) should be used to create a strong edge that sets the roundabout apart Note: Becase roundabouts allow the slow, but from the roadway. -

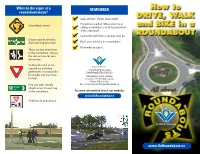

How to Drive, Walk & Bike in a Roundabout

What do the signs at a REMEMBER roundabout mean? Look and plan ahead. Slow down! Pedestrians go first. When entering or Roundabout ahead. exiting a roundabout, yield to pedestrians at the crosswalk. Look to the left, find a safe gap, then go. Choose your destination. Start planning your route. Don’t pass vehicles in a roundabout. Remember to signal. There are two entry lanes to the roundabout. Choose the correct lane for your destination. Yield to all traffic in the roundabout including TRANSPORTATION AND pedestrians at crosswalks. ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES Remember you may have 150 Frederick Street, 7th Floor to stop! Kitchener ON N2G 4J3 Canada Phone: 519-575-4558 Flag exit signs identify Email: [email protected] street names for each leg of the roundabout. For more information check our website: www.GoRoundabout.ca Yield here to pedestrians. www.GoRoundabout.ca Updated January 2011 MOWTO HAT IS A ROUNDABOUT? HOW TO DRIVE IN A ROUNDABOUT TIPS FOR CYCLISTS A roundabout is an intersection at which ᮣ Slow down when A cyclist has two choices at a roundabout. Your all traffic circulates counterclockwise approaching a choice will depend on your degree of comfort riding roundabout. in traffic. around a centre island. ᮣ Observe lane signs. For experienced cyclists: Choose the correct ● Ride as if you were driving entry lane. a car. Yield Line ᮣ Expect pedestrians ● Merge into the travel lane Central and yield to them at before the bike lane or shoulder ends. Island all crosswalks. ● Ride in the middle of your lane; don’t hug the curb. Turning right and turning left ᮣ Wait for a gap in ● Use hand signals and signal as if you were a traffic before motorist. -

City of Davis Bicycle Plan 2009

CITY OF DAVIS BICYCLE PLAN 2009 City of Davis Bicycle Advisory Commission In February of 2005, the Davis City Council established the Bicycle Advisory Commission to address bicycle issues related to education, enforcement, engineering and encouragement. Membership of the Commission may include representatives from the general public, the Davis Bicycle Club, UCD Administration, and UCD students, among others. 2008-2009 Bicycle Advisory Commission Members John Berg Chair Jack Kenward Vice-Chair Earl Bossard Commissioner Kelli O’Neill Commissioner Alan Jackman Commissioner Virginia Matzek Commissioner Angel York Commissioner Joe Krovoza Alternate David Takemoto-Weerts Ex-Officio 2007-2008 Bicycle Advisory Commission Members John Berg Chair Jack Kenward Vice-Chair Earl Bossard Commissioner Dan Kehew Commissioner Anthony Palmere Commissioner Lise Smidth Commissioner Ken Gaines Commissioner Kelli O’Neill Alternate David Takemoto-Weerts Ex-Officio Council Liaison to the Commission Sue Greenwald Staff Liaison to the Commission Tara Goddard 2 Resolution of Adoption RESOLUTION NO._______________, SERIES 2009 RESOLUTION ADOPTING THE CITY OF DAVIS BICYCLE PLAN WHEREAS, the Metropolitan Transportation Plan supports and encourages local agencies to develop comprehensive bicycle plans consistent with the regional plan; and WHEREAS, the City of Davis Bicycle Advisory Commission (BAC) has reviewed the Bicycle Plan and recommends its adoption; and WHEREAS, the proposed Bicycle Plan is consistent with the City of Davis General Plan and General Plan environmental -

Absolute Bikes American Cycle & Fitness-The Trek Bicycle Stores Of

The Top 100 Retailers for 2008 were selected because they excel in three areas: market share, community outreach and store appearance. However, each store has its own unique formula for success. We asked each store owner to share what he or she believes sets them apart from their peers. Read on to learn their tricks of the trade. denotes repeat Top 100 retailer Absolute Bikes American Cycle & Fitness-The Trek Action Sports Flagstaff, AZ Bicycle Stores of Metro Detroit Bakersfi eld, CA Number of locations: 2 Number of locations: 1 Years in business: 19 Walled Lake, MI Years in business: 20 Number of locations: 5 Square footage (main location): 2,000 Square footage: 23,500 Years in business: more than 75 Number of employees at height of season: 12 Number of employees at height of season: 42 Square footage (main location): 10,500 Owner: Kenneth Lane Owner: Kerry Ryan Number of employees at height of season: 75 Manager: Anthony Quintile Manager: Sam Ames Owners: Michael Reuter, Mark Eickmann, Ken What Sets You Apart: We constantly reassess how we are performing on Stonehouse What Sets You Apart: Action Sports is a specialty multi-sport store with all levels. We review any mistakes we have made—dissatisfi ed customer Managers: Matt Marino, Steven Straub more than 800 bicycles on the fl oor, including 13 road and mountain brands scenarios, for example—and try to fi gure out how we could have handled and six brands of cruisers and BMX bikes—a rare combination of Trek the situation better. There is never a point at which we say, “This is as good What Sets You Apart: We put a lot of effort and money to make our stores and Specialized alongside Scott, Cannondale, Cervélo, Colnago, Pinarello, as we are going to get,” and rest on our laurels.