CASE NO. SC06-156 V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Clones Stick Together

TVhome The Daily Home April 12 - 18, 2015 Clones Stick Together Sarah (Tatiana Maslany) is on a mission to find the 000208858R1 truth about the clones on season three of “Orphan Black,” premiering Saturday at 8 p.m. on BBC America. The Future of Banking? We’ve Got A 167 Year Head Start. You can now deposit checks directly from your smartphone by using FNB’s Mobile App for iPhones and Android devices. No more hurrying to the bank; handle your deposits from virtually anywhere with the Mobile Remote Deposit option available in our Mobile App today. (256) 362-2334 | www.fnbtalladega.com Some products or services have a fee or require enrollment and approval. Some restrictions may apply. Please visit your nearest branch for details. 000209980r1 2 THE DAILY HOME / TV HOME Sun., April 12, 2015 — Sat., April 18, 2015 DISH AT&T DIRECTV CABLE CHARTER CHARTER PELL CITY PELL ANNISTON CABLE ONE CABLE TALLADEGA SYLACAUGA BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM CONVERSION CABLE COOSA SPORTS WBRC 6 6 7 7 6 6 6 6 AUTO RACING Friday WBIQ 10 4 10 10 10 10 6 p.m. FS1 St. John’s Red Storm at Drag Racing WCIQ 7 10 4 Creighton Blue Jays (Live) WVTM 13 13 5 5 13 13 13 13 Sunday Saturday WTTO 21 8 9 9 8 21 21 21 7 p.m. ESPN2 Summitracing.com 12 p.m. ESPN2 Vanderbilt Com- WUOA 23 14 6 6 23 23 23 NHRA Nationals from The Strip at modores at South Carolina WEAC 24 24 Las Vegas Motor Speedway in Las Gamecocks (Live) WJSU 40 4 4 40 Vegas (Taped) 2 p.m. -

On the Ball! One of the Most Recognizable Stars on the U.S

TVhome The Daily Home June 7 - 13, 2015 On the Ball! One of the most recognizable stars on the U.S. Women’s World Cup roster, Hope Solo tends the goal as the U.S. 000208858R1 Women’s National Team takes on Sweden in the “2015 FIFA Women’s World Cup,” airing Friday at 7 p.m. on FOX. The Future of Banking? We’ve Got A 167 Year Head Start. You can now deposit checks directly from your smartphone by using FNB’s Mobile App for iPhones and Android devices. No more hurrying to the bank; handle your deposits from virtually anywhere with the Mobile Remote Deposit option available in our Mobile App today. (256) 362-2334 | www.fnbtalladega.com Some products or services have a fee or require enrollment and approval. Some restrictions may apply. Please visit your nearest branch for details. 000209980r1 2 THE DAILY HOME / TV HOME Sun., June 7, 2015 — Sat., June 13, 2015 DISH AT&T CABLE DIRECTV CHARTER CHARTER PELL CITY PELL ANNISTON CABLE ONE CABLE TALLADEGA SYLACAUGA SPORTS BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM CONVERSION CABLE COOSA WBRC 6 6 7 7 6 6 6 6 AUTO RACING 5 p.m. ESPN2 2015 NCAA Baseball WBIQ 10 4 10 10 10 10 Championship Super Regionals: Drag Racing Site 7, Game 2 (Live) WCIQ 7 10 4 WVTM 13 13 5 5 13 13 13 13 Sunday Monday WTTO 21 8 9 9 8 21 21 21 8 p.m. ESPN2 Toyota NHRA Sum- 12 p.m. ESPN2 2015 NCAA Baseball WUOA 23 14 6 6 23 23 23 mernationals from Old Bridge Championship Super Regionals Township Race. -

Retinal Transplantation in a Rodent Model of Retinitis Pigmentosa

Retinal transplantation in a rodent model of Retinitis Pigmentosa Anthony S L Kwan Institnte of Ophthalmology University College London A dissertation submitted for the degree of Doctor of Medicine at the University of London 2003 ProQuest Number: 10014454 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10014454 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Table of Contents Preface 5 Acknowledgements 6 Abbreviations 8 List of figures 10 List of tables 13 Abstract 14 Chapters 1.0. Introduction 16 1.1. Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) 19 1.1.1. Morphological changes in the RP retina 21 1.1.2. Potential treatments for RP 27 1.2. A mouse model of retinitis pigmentosa 34 1.2.1. Origin of the retinal degeneration (rd) mouse 34 1.2.2. Morphological changes in rd phenotype 35 1.2.3. Visual function of the rd mouse 48 1.2.4. Experimental treatments in the rd mouse 53 1.3. Background of experimental retinal transplantation in rodent models 59 1.3.1. Donor cells 59 1.3.2. -

Involuntary Manslaughter by Text Charles Adside III University of Michigan

University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Volume 52 | Issue 3 2019 The nnoI cent Villain: Involuntary Manslaughter by Text Charles Adside III University of Michigan Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr Part of the Communications Law Commons, Criminal Law Commons, and the Internet Law Commons Recommended Citation Charles Adside III, The Innocent Villain: Involuntary Manslaughter by Text, 52 U. Mich. J. L. Reform 731 (2019). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr/vol52/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE INNOCENT VILLAIN: INVOLUNTARY MANSLAUGHTER BY TEXT Charles Adside III* Michelle Carter’s texts instructing her mentally ill online boyfriend to commit suicide offended the social moral code. But the law does not categorize all morally reprehensible behavior as criminal. Commonwealth v. Carter is unprecedented in manslaughter law because Carter was convicted on the theory that she was virtually present as opposed to physically present—at the crime scene. The court’s reasoning is expansive, as the framework it employs is excessively vague and does not provide fair notice to the public of which actions constitute involuntary manslaughter. Disturbingly, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court affirmed the trial court’s logic. This Article concludes that a conviction based upon a virtual-presence theory is unconstitutional, as it is void-for-vagueness. -

Trygge Toven

TRYGGE TOVEN MUSIC SUPERVISOR RECENT FEATURES AND EPISODIC WORK WESTWORLD (S3) Lisa Joy and Jonathan Nolan, creators HBO 6 UNDERGROUND Michael Bay, dir. Netflix DEEP WATER Adrian Lyne, dir. Fox DOLEMITE IS MY NAME Craig Brewer, dir. Netflix FINDING OHANA Jude Weng, dir. Netflix SPIES IN DISGUISE Nick Bruno & Troy Quane, dir. Blue Sky ALWAYS BE MY MAYBE Nahnatcha Khan, dir. Netflix FANTASY ISLAND Jeff Wadlow, dir. Columbia Pictures SEXTUPLETS Michael Tiddes, dir. Netflix SHAFT Time Story, dir. New Line BRIGHTBURN David Yarovesky, dir. Sony RED SHOES & THE 7 DWARFS Sung-ho Hong, dir. Locus THE PREDATOR Shane Black, dir. Fox IT’S TIME Frank Waldeck, dir. Mt. Philo Films MOTION PICTURES (continued) IBIZA Alex Richanbach, dir. Netflix AVENGERS: INFINITY WAR (Music Coordinator) Anthony Russo, Joe Russo, dirs. Disney BLACK PANTHER (Music Coordinator) Ryan Coogler, dir. Disney FINDING STEVE MCQUEEN Mark Steven Johnson, dir. AMBI Group THOR: RAGNAROK (Music Coordinator) Taika Waititi, dir. Disney WHERE’S THE MONEY? Scott Zabielski, dir. Lionsgate NAKED Michael Tiddes, dir. Netflix SPIDER-MAN: HOMECOMING (Music Coordinator) Jon Watts, dir. Columbia Pictures ALL EYEZ ON ME Benny Boom, dir. Morgan Creek AMERICAN MADE (Music Coordinator) Doug Liman, dir. Universal Pictures MEGAN LEAVEY (Music Coordinator) Gabriela Cowperthwaite, dir. LD Entertainment GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY VOL. 2 (Music Coordinator) James Gunn, dir. Disney SING (Music Coordinator) Garth Jennings, dir. Illumination TRUE MEMOIRS OF AN INTERNATIONAL ASSASSIN Jeff Wadlow, dir. Netflix DOCTOR STRANGE (Music Coordinator) Scott Derrickson, dir. Marvel TROLLS (Music Coordinator) Mike Mitchell, dir. DreamWorks Animation MOTION PICTURES (continued) SKIPTRACE (Music Coordinator) Renny Harlin, dir. Saban Films A CINDERELLA STORY: IF THE SHOE FITS Michelle Johnston, dir. -

The George Black Begins Its Summer Service

The WEDNESDAY, MAY 20, 2015 • VOL. 26, NO. 2 $1.50 Smile: Here come the KLONDIKE tourists! SUN The George Black begins its summer service The George Black hit the river early on the morning of Friday, May 15. Photo by Dan Davidson. in this Issue Fire on the Dome 3 Guy Davis in Concert 7 World Heritage thoughts 8 Max’s has Family left homeless by fire by French Medal of Honour What UNESCO designation meant long distance supported by the community. presented for WWII service. to a declining Nova Scotia town. calling cards now! What to see and do in Dawson! 2 Live Words in Whitehorse 6 Gerties is a Municipal Heritage Site 11 Wildland Fire Report 17 Uffish Thoughts 4 McDonald Lodge update 8 TV Guide 12-16 Classifieds 19 Smoke & Teacup 5 Helping farm fire victims 9 DCMF previews 17 City notices 20 P2 WEDNESDAY, MAY 20, 2015 THE KLONDIKE SUN What to SEE AND DO in DAWSON now: This free public service helps our readers find their way through the many (enter through the back door). Inspire and be inspired by other artists. Bring activities all over town. Any small happening may need preparation and planning, hyouratha own y ideasoga andwith painting joanne surfaces. van Paints, nostrand: brushes & easels are supplied, no so let us know in good time! To join this listing contact the office at klondikesun@ instruction offered. Eventsnorthwestel.net. Mondays: 6:45-8 p.m., WEEKEND ON THE WING: Thursdays: 5:45-7 p.m. & Saturdays 9-10:30 a.m. In the KIAC Ballroom. -

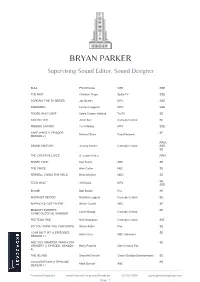

BRYAN PARKER Supervising Sound Editor, Sound Designer

BRYAN PARKER Supervising Sound Editor, Sound Designer BULL Phil McGraw CBS SSE THE MIST Christian Torpe Spike TV SSE SCREAM: THE TV SERIES Jay Beattie MTV SSE AWKWARD Lauren Iungerich MTV SSE THOSE WHO CAN'T Adam Cayton-Holland TruTV SE IDIOTSITTER Jillian Bell Comedy Central SE FINDING CARTER Terri Minsky MTV SSE CAKE WARS (1 EPISODE, SE Michael Shea Food Network SEASON 2) RRM, DRUNK HISTORY Jeremy Konner Comedy Central SSE, SE THE CREATIVE LIVES G. Lewis Heslet RRM SHARK TANK Ken Fuchs ABC SE THE VOICE Alan Carter NBC SE FERRELL TAKES THE FIELD Brian McGinn HBO SE SE, TEEN WOLF Jeff Davis MTV SSE BOOM! Bob Boden Fox SE ANOTHER PERIOD Natasha Leggero Comedy Central SE AMERICA'S GOT TALENT Simon Cowell NBC SE BRIDGET EVERETT: SE Lance Bangs Comedy Central GYNECOLOGICAL WONDER PRETEND TIME Nick Swardson Comedy Central SSE SO YOU THINK YOU CAN DANCE Simon Fuller Fox SE I CAN DO THAT (3 EPISODES, SE Alan Carter NBC Universal SEASON 1) ARE YOU SMARTER THAN A 5TH SE GRADER? (1 EPISODE, SEASON Barry Poznick 20th Century Fox 6) THE ISLAND Sean McClocklin Geach Studios Entertainment SE 500 QUESTIONS (1 EPISODE, SE Mark Burnett ABC SEASON 1) Formosa Broadcast www.FormosaGroup.com/Broadcast 323.853.0008 [email protected] Page 1 KEN JEONG MADE ME DO IT (TV SE Peter Segal MTV MOVIE) EYE CANDY Christian Taylor MTV SSE KOBE BRYANT'S MUSE (TV SSE Gotham Chopra Showtime SPECIAL) REDNECK ISLAND Nick Murray CMT SE THE AMAZING RACE Elisa Doganier CBS SE Image not found or type unknown HAPPYLAND (TV MINI SERIES) Ben Epstein MTV SE ON THE MENU (1 EPISODE, SE Richard A. -

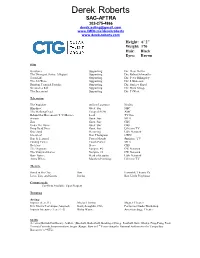

Derek Roberts SAG-AFTRA 302-275-4866 [email protected]

Derek Roberts SAG-AFTRA 302-275-4866 [email protected] www.IMDb.me/derekroberts www.derek-roberts.com Height: 6’ 2” Weight: 170 Hair: Black Eyes: Brown Film Geostorm Supporting Dir: Dean Devlin The Divergent Series: Allegiant Supporting Dir: Robert Schwentke Term Life Supporting Dir: Peter Billingsley The 5th Wave Supporting Dir: J. Blakeson Random Tropical Paradise Supporting Dir: Sanjeev Sirpal Stressed to Kill Supporting Dir: Mark Savage The Sacrament Supporting Dir: Ti West Television The Punisher Officer Lawrence Netflix Blindspot Guest Star NBC The Walking Dead Escaped POW AMC Behind the Movement (T.V. Movie) Lead TV One Scream Guest Star MTV Zoo Guest Star CBS Under the Dome Guest Star CBS Drop Dead Diva Guest Star Lifetime TV Graceland Recurring USA Network Greenleaf Dan Thompson OWN Hap & Leonard Pastor Moody Sundance TV Finding Carter Coach Parker MTV Reckless Steve CBS The Originals Vampire #2 CW Network The Vampire Diaries Vampire #2 CW Network Burn Notice Head of Security USA Network Army Wives Matthew Pennings Lifetime TV Theatre Saved in the City Sam Ensemble Theatre Co. Love, Lies, and Games Darius Best Little Playhouse Commercials Conflicts Available Upon Request Training Acting: Improv (Level 1) Michael Lutton Magnet Theater Eric Morris Technique (Adapted) Kathy Laughlin, CSA Performer Studio Workshop Improv Intensive (Level 1-3) Ricky Wayne American Stage Theater Skills Accents (British/Caribbean), Athletic (Baseball, Basketball, Bowling-220avg, Football, Golf-12hdcp, Ping-Pong, Pool, Tennis) Comedy, Improvisation, Singer (Range: Bass to 1st Tenor-Sang the National Anthem for the Tampa Bay Buccaneer’s *NFL) . -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers in Bessemer

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; BLACKISH) -

TV Shows (VOD)

TV Shows (VOD) 11.22.63 12 Monkeys 13 Reasons Why 2 Broke Girls 24 24 Legacy 3% 30 Rock 8 Simple Rules 9-1-1 90210 A Discovery of Witches A Million Little Things A Place To Call Home A Series of Unfortunate Events... APB Absentia Adventure Time Africa Eye to Eye with the Unk... Aftermath (2016) Agatha Christies Poirot Alex, Inc. Alexa and Katie Alias Alias Grace All American (2018) All or Nothing: Manchester Cit... Altered Carbon American Crime American Crime Story American Dad! American Gods American Horror Story American Housewife American Playboy The Hugh Hefn...American Vandal Americas Got Talent Americas Next Top Model Anachnu BaMapa Ananda Ancient Aliens And Then There Were None Angels in America Anger Management Animal Kingdom (2016) Anne with an E Anthony Bourdain Parts Unknown...Apple Tree Yard Aquarius (2015) Archer (2009) Arrested Development Arrow Ascension Ash vs Evil Dead Atlanta Atypical Avatar The Last Airbender Awkward. Baby Daddy Babylon Berlin Bad Blood (2017) Bad Education Ballers Band of Brothers Banshee Barbarians Rising Barry Bates Motel Battlestar Galactica (2003) Beauty and the Beast (2012) Being Human Berlin Station Better Call Saul Better Things Beyond Big Brother Big Little Lies Big Love Big Mouth Bill Nye Saves the World Billions Bitten Black Lightning Black Mirror Black Sails Blindspot Blood Drive Bloodline Blue Bloods Blue Mountain State Blue Natalie Blue Planet II BoJack Horseman Boardwalk Empire Bobs Burgers Bodyguard (2018) Bones Borgen Bosch BrainDead Breaking Bad Brickleberry Britannia Broad City Broadchurch Broken (2017) Brooklyn Nine-Nine Bull (2016) Bulletproof Burn Notice CSI Crime Scene Investigation CSI Miami CSI NY Cable Girls Californication Call the Midwife Cardinal Carl Webers The Family Busines.. -

Black Female School Counselors' Experiences

INTERCHANGEABLE OPPRESSION: BLACK FEMALE SCHOOL COUNSELORS’ EXPERIENCES WITH BLACK ADOLESCENT GIRLS IN URBAN MIDDLE SCHOOLS Sonya June Hicks Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Education, Indiana University August 2021 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty of Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Tambra Jackson Ph.D., Chair ______________________________________ Chalmer Thompson Ph.D. May 26, 2021 ______________________________________ Sha’Kema Blackmon Ph.D. ______________________________________ Crystal Morton Ph.D. ii © 2021 Sonya June Hicks iii DEDICATION This manuscript is dedicated to the Black female educators who strive daily to nurture, protect, and inspire Black girls to achieve, both individually and collectively. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I first thank God, and my Lord Jesus Christ for granting me the mental and physical strength to complete this project. To my family. First, my dear, loving, and amazing husband. I thank you for you for providing me unending support, encouragement, inspiration, and love throughout this PhD journey. I love you John…We did this together. Next, to my children. You inspire me to be the woman God wants me to be. You give me life, and you are Gifts from God that I am ever thankful for. Keep making me proud and be the individuals God wants you to be. I love you, Jillian (Javonte), and Matthew. To my loving parents. I thank my parents “James” Herman Bond and Ola June Bond (Jones) for giving me life and instilling in me God’s principles of love and faithfulness.