'Political Screening in Hong Kong'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gaza-Israel: the Legal and the Military View Transcript

Gaza-Israel: The Legal and the Military View Transcript Date: Wednesday, 7 October 2015 - 6:00PM Location: Barnard's Inn Hall 07 October 2015 Gaza-Israel: The Legal and Military View Professor Sir Geoffrey Nice QC General Sir Nick Parker For long enough commentators have usually assumed the Israel - Palestine armed conflict might be lawful, even if individual incidents on both sides attracted condemnation. But is that assumption right? May the conflict lack legality altogether, on one side or both? Have there been war crimes committed by both sides as many suggest? The 2014 Israeli – Gaza conflict (that lasted some 52 days and that was called 'Operation Protective Edge' by the Israeli Defence Force) allows a way to explore some of the underlying issues of the overall conflict. General Sir Nick Parker explains how he advised Geoffrey Nice to approach the conflict's legality and reality from a military point of view. Geoffrey Nice explains what conclusions he then reached. Were war crimes committed by either side? Introduction No human is on this earth as a volunteer; we are all created by an act of force, sometimes of violence just as the universe itself arrived by force. We do not leave the world voluntarily but often by the force of disease. As pressed men on earth we operate according to rules of nature – gravity, energy etc. – and the rules we make for ourselves but focus much attention on what to do when our rules are broken, less on how to save ourselves from ever breaking them. That thought certainly will feature in later lectures on prison and sex in this last year of my lectures as Gresham Professor of Law but is also central to this and the next lecture both on Israel and on parts of its continuing conflict with Gaza. -

Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016

Journal of US-China Public Administration, August 2016, Vol. 13, No. 8, 499-517 doi: 10.17265/1548-6591/2016.08.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016 Chung Fun Steven Hung The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong After direct elections were instituted in Hong Kong, politicization inevitably followed democratization. This paper intends to evaluate how political parties’ politics happened in Hong Kong’s recent history. The research was conducted through historical comparative analysis, with the context of Hong Kong during the sovereignty transition and the interim period of democratization being crucial. For the implementation of “one country, two systems”, political democratization was hindered and distinct political scenarios of Hong Kong’s transformation were made. The democratic forces had no alternative but to seek more radicalized politics, which caused a decisive fragmentation of the local political parties where the establishment camp was inevitable and the democratic blocs were split into many more small groups individually. It is harmful. It is not conducive to unity and for the common interests of the publics. This paper explores and evaluates the political history of Hong Kong and the ways in which the limited democratization hinders the progress of Hong Kong’s transformation. Keywords: election politics, historical comparative, ruling, democratization The democratizing element of the Hong Kong political system was bounded within the Legislative Council under the principle of the separation of powers of the three governing branches, Executive, Legislative, and Judicial. Popular elections for the Hong Kong legislature were introduced and implemented for 25 years (1991-2016) and there were eight terms of general elections for the Legislative Council. -

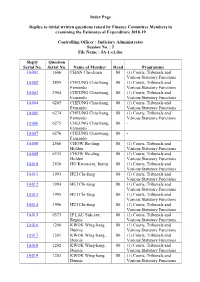

Index Page Replies to Initial Written Questions Raised by Finance

Index Page Replies to initial written questions raised by Finance Committee Members in examining the Estimates of Expenditure 2018-19 Controlling Officer : Judiciary Administrator Session No. : 2 File Name : JA-1-e1.doc Reply Question Serial No. Serial No. Name of Member Head Programme JA001 1606 CHAN Chi-chuen 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA002 2899 CHEUNG Chiu-hung, 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Fernando Various Statutory Functions JA003 2904 CHEUNG Chiu-hung, 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Fernando Various Statutory Functions JA004 6205 CHEUNG Chiu-hung, 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Fernando Various Statutory Functions JA005 6274 CHEUNG Chiu-hung, 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Fernando Various Statutory Functions JA006 6275 CHEUNG Chiu-hung, 80 - Fernando JA007 6276 CHEUNG Chiu-hung, 80 - Fernando JA008 2566 CHOW Ho-ding, 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Holden Various Statutory Functions JA009 6335 CHOW Ho-ding, 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Holden Various Statutory Functions JA010 2836 HO Kwan-yiu, Junius 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA011 1993 HUI Chi-fung 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA012 1994 HUI Chi-fung 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA013 1995 HUI Chi-fung 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA014 1996 HUI Chi-fung 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA015 0373 IP LAU Suk-yee, 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Regina Various Statutory Functions JA016 1200 KWOK Wing-hang, 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Dennis Various Statutory Functions JA017 1201 KWOK Wing-hang, 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Dennis Various Statutory Functions JA018 1202 KWOK Wing-hang, 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Dennis Various Statutory Functions JA019 1203 KWOK Wing-hang, 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Dennis Various Statutory Functions Reply Question Serial No. -

Women Readers of Middle Temple Celebrating 100 Years of Women at Middle Temple the Incorporated Council of Law Reporting for England and Wales

The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple Middle Society Honourable the The of 2019 Issue 59 Michaelmas 2019 Issue 59 Women Readers of Middle Temple Celebrating 100 Years of Women at Middle Temple The Incorporated Council of Law Reporting for England and Wales Practice Note (Relevance of Law Reporting) [2019] ICLR 1 Catchwords — Indexing of case law — Structured taxonomy of subject matter — Identification of legal issues raised in particular cases — Legal and factual context — “Words and phrases” con- strued — Relevant legislation — European and International instruments The common law, whose origins were said to date from the reign of King Henry II, was based on the notion of a single set of laws consistently applied across the whole of England and Wales. A key element in its consistency was the principle of stare decisis, according to which decisions of the senior courts created binding precedents to be followed by courts of equal or lower status in later cases. In order to follow a precedent, the courts first needed to be aware of its existence, which in turn meant that it had to be recorded and published in some way. Reporting of cases began in the form of the Year Books, which in the 16th century gave way to the publication of cases by individual reporters, known collectively as the Nominate Reports. However, by the middle of the 19th century, the variety of reports and the variability of their quality were such as to provoke increasing criticism from senior practitioners and the judiciary. The solution proposed was the establishment of a body, backed by the Inns of Court and the Law Society, which would be responsible for the publication of accurate coverage of the decisions of senior courts in England and Wales. -

Civic Party (Cp)

立法會 CB(2)1335/17-18(04)號文件 LC Paper No. CB(2)1335/17-18(04) CIVIC PARTY (CP) Submission to the United Nations UNIVERSAL PERIODIC REVIEW Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) CHINA 31st session of the UPR Working Group of the Human Rights Council November 2018 Introduction 1. We are making a stakeholder’s submission in our capacity as a political party of the pro-democracy camp in Hong Kong for the 2018 Universal Periodic Review on the People's Republic of China (PRC), and in particular, the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR). Currently, our party has five members elected to the Hong Kong Legislative Council, the unicameral legislature of HKSAR. 2. In the Universal Periodic Reviews of PRC in 2009 and 2013, not much attention was paid to the human rights, political, and social developments in the HKSAR, whilst some positive comments were reported on the HKSAR situation. i We wish to highlight that there have been substantial changes to the actual implementation of human rights in Hong Kong since the last reviews, which should be pinpointed for assessment in this Universal Periodic Review. In particular, as a pro-democracy political party with members in public office at the Legislative Council (LegCo), we wish to draw the Council’s attention to issues related to the political structure, election methods and operations, and the exercise of freedom and rights within and outside the Legislative Council in HKSAR. Most notably, recent incidents demonstrate that the PRC and HKSAR authorities have not addressed recommendations made by the Human Rights Committee in previous concluding observations in assessing the implementation of International Convention on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). -

Stephen David Mau

STEPHEN DAVID MAU Hong Kong Office Telephone: 852-3400-3865 E-mail: [email protected] EXPERIENCE: The Hong Kong Polytechnic University Hong Kong August 2007 – Date Assistant Professor - Law in the Dept. of Building & Real Estate. Aculex Transnational Inc. Hong Kong January 2006 – July 2007 Senior Consultant. Hellings Morgan Associates Hong Kong November 1995 – December 2005 Consultant. City University of Hong Kong Hong Kong March 1993 - October 1995 Assistant Professor - Law. Nishiyama, Mukai, Leewong, Evans & Saldin Hong Kong October 1992 - January 1993 Consultant Mau Law Office Rye, New Hampshire May 1985 - December 1991 Solo Practice. Fryer, Boutin, Warhall & Solomon, P.A. Londonderry, New Hampshire February 1984 - April 1985 Associate. EDUCATION: McGeorge School of Law - University of the Pacific - Sacramento, CA LL.M., Transnational Business Practice, December 1992. University of Connecticut School of Law - West Hartford, CT J.D., May 1983. University of Exeter Faculty of Law - Exeter, England Exchange Program in International Law, Fall of 1982. London School of Economics - London, England Notre Dame Summer Program in International Law, Summer of 1981. Brandeis University - Waltham, MA B.A. Politics, May 1980. St. Paul's School, Advanced Studies Program - Concord, NH LANGUAGES: English Cantonese French Stephen David MAU, page 2. BAR ADMISSIONS and PROFESSIONAL MEMBERSHIPS: State of New Hampshire, October 1983 U.S. District Court for the District of New Hampshire, October 1983 U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the First Circuit, March 1986 Member, Chartered Institute of Arbitrators Member, American Arbitration Association HKIAC Accredited Mediator (General) PUBLICATIONS: Equity, the Third World and the Moon Treaty 8 Suffolk Transnational Law Journal 221 (1984) Current Arbitration Practice in Hong Kong Arbitration [Journal of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators], Vol. -

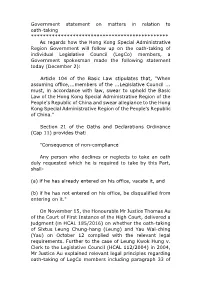

Government Statement on Matters in Relation to Oath-Taking

Government statement on matters in relation to oath-taking ********************************************** As regards how the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government will follow up on the oath-taking of individual Legislative Council (LegCo) members, a Government spokesman made the following statement today (December 2): Article 104 of the Basic Law stipulates that, "When assuming office,...members of the ...Legislative Council ... must, in accordance with law, swear to uphold the Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China and swear allegiance to the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China." Section 21 of the Oaths and Declarations Ordinance (Cap 11) provides that: "Consequence of non-compliance Any person who declines or neglects to take an oath duly requested which he is required to take by this Part, shall- (a) if he has already entered on his office, vacate it, and (b) if he has not entered on his office, be disqualified from entering on it." On November 15, the Honourable Mr Justice Thomas Au of the Court of First Instance of the High Court, delivered a judgment (in HCAL 185/2016) on whether the oath-taking of Sixtus Leung Chung-hang (Leung) and Yau Wai-ching (Yau) on October 12 complied with the relevant legal requirements. Further to the case of Leung Kwok Hung v. Clerk to the Legislative Council (HCAL 112/2004) in 2004, Mr Justice Au explained relevant legal principles regarding oath-taking of LegCo members including paragraph 33 of the judgment: "In the premises, the fundamental and essential question to be answered in determining the validity of the taking of an oath is whether it can be seen objectively that the person taking the oath faithfully and truthfully commits and binds himself or herself to uphold and abide by the obligations set out in the oath." Leung and Yau appealed against the above judgment of Mr Justice Au. -

081216-Keast-YAIA-HK

Hong Kong’s disaffected youths – Is the criticism warranted? December 7, 2016 Jacinta Keast Sixtus ‘Baggio’ Leung and Yau Wai-ching, two young legislators from the localist Youngspiration party, have been barred from Hong Kong’s legislative council (LegCo). Never has China’s National People’s Congress (NPC) jumped to an interpretation on a matter in Hong Kong without a prior request from the local government or courts. This comes after the pair modified their oaths, including enunciating the word ‘China’ as ‘Cheena’ (支那), a derogatory term used by the Japanese in World War II, using expletives to refer to the People’s Republic of China, and waving around blue ‘Hong Kong is not China’ banners at their swearing in. Commentators, including those from the pan-democratic side of the legislature, have called their behaviour infantile, ignorant and thuggish, and have demanded ‘that the hooligans be locked up’. But is this criticism warranted? A growing tide of anti-Mainlander vitriol has been building in Hong Kong since it was handed back to the People’s Republic of China in 1997 under a special constitution termed The Basic Law. In theory, the constitution gave Hong Kong special privileges the Mainland did not enjoy—a policy called ‘One Country, Two Systems’. But in practice, more and more Hong Kong residents feel that the long arm of Beijing’s soft power is extending over the territory. The Occupy movement and later the 2014 Umbrella Revolution began once it was revealed that the Chinese government would be pre-screening candidates for the 2017 Hong Kong Chief Executive election, the election for Hong Kong’s top official. -

Highspeed Rail Links to Airports Ahead

4 | Thursday, April 30, 2020 HONG KONG EDITION | CHINA DAILY CHINA Beijing Flying fish Court rejects appeal by med staff activist Edward Leung By CHEN ZIMO in Hong Kong endured [email protected] Participants in the The Court of Appeal of Hong uncertainty Kong on Wednesday dismissed the riots showed a appeal lodged by local independ- degree of By WANG XIAODONG ence activist Edward Leung Tin-kei [email protected] against his six-year jail term for premeditation in rioting in 2016, saying the sentence committing the When Chang Zhigang, a doctor of handed down to him by the Court critical medicine at Beijing Hospital, of First Instance was “reasonable” crime when they arrived at Tongji Hospital in Wuhan and supported by “sufficient evi- attacked unarmed on Jan 26, he and his colleagues dence”. faced a difficult situation — a rapidly The court also ruled against Lo police officers with increasing number of COVID-19 Kin-man and Wong Ka-kui, who serious violence.” patients, a severe shortage of beds, a were also convicted of rioting and lack of standard negative-pressure jailed for the same incident on Feb The Court of Appeal wards for treatment of infectious dis- 8 and 9, 2016. They filed the appeal eases and exhausted local doctors together with Leung. Chief Judge of the High Court of and nurses. In the written summary of the Hong Kong Jeremy Poon Shiu- Patients were generally in a nega- ruling, the court said sentencing chor, one of the three judges who tive mood. Those who could not get for the offense of rioting “must presided over the appeal case, fur- admitted had fears they would not reflect the law’s determination to ther noted that Leung had been get treated and would infect their maintain public order, and send a present since the riot began and family members. -

Chapter 6 Hong Kong

CHAPTER 6 HONG KONG Key Findings • The Hong Kong government’s proposal of a bill that would allow for extraditions to mainland China sparked the territory’s worst political crisis since its 1997 handover to the Mainland from the United Kingdom. China’s encroachment on Hong Kong’s auton- omy and its suppression of prodemocracy voices in recent years have fueled opposition, with many protesters now seeing the current demonstrations as Hong Kong’s last stand to preserve its freedoms. Protesters voiced five demands: (1) formal with- drawal of the bill; (2) establishing an independent inquiry into police brutality; (3) removing the designation of the protests as “riots;” (4) releasing all those arrested during the movement; and (5) instituting universal suffrage. • After unprecedented protests against the extradition bill, Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam suspended the measure in June 2019, dealing a blow to Beijing which had backed the legislation and crippling her political agenda. Her promise in September to formally withdraw the bill came after months of protests and escalation by the Hong Kong police seeking to quell demonstrations. The Hong Kong police used increasingly aggressive tactics against protesters, resulting in calls for an independent inquiry into police abuses. • Despite millions of demonstrators—spanning ages, religions, and professions—taking to the streets in largely peaceful pro- test, the Lam Administration continues to align itself with Bei- jing and only conceded to one of the five protester demands. In an attempt to conflate the bolder actions of a few with the largely peaceful protests, Chinese officials have compared the movement to “terrorism” and a “color revolution,” and have im- plicitly threatened to deploy its security forces from outside Hong Kong to suppress the demonstrations. -

Property Connect

Property Connect December 2020 | A newsletter from the Department of Property Acts of kindness and Replicating the support rewarded classroom online Property students Olivia Andrevski and Filip Ograbek have Just as the Property Department’s academic staff had to quickly each been awarded a prize of $2,500 as part of the Grace Shi adjust to teaching and facilitating courses in an online Acts of Kindness and Support of Fellow Property Students environment during lockdown, students also struggled to Award 2020. replicate physical learning environments. The award was made possible thanks to a generous donation Olivia Andrevski, a third year BCom/BProp conjoint student, says to the Property Department by alumnus Grace Shi, a that in previous semesters she benefitted greatly from the use of Residential Property Manager with LJ Hooker Ponsonby who study groups, face-to-face chats with lecturers, and the campus completed her BCom/BProp conjoint degree in 2016. library and was concerned how she would perform academically without these resources. However, Olivia found that the Both students were chosen for their significant acts of University’s online learning platform Piazza was extremely kindness and support to their peers and lecturers throughout beneficial during lockdown. the year. Olivia and Filip were nominated respectively by Head of Property Professor Deborah Levy and ALES President Anna “Online lectures, tests, assignments and exams Creahan in collaboration with the ALES committee. definitely took some getting used to, but the Filip Ograbek “Despite the circumstances of 2020, Filip has Piazza platform let me seek help on areas of been hard-working and motivated and has consistently gone out of his way to motivate and offer help and support to other uncertainty in my courses while helping other property students. -

H. Res. 422 in the House of Representatives, U

H. Res. 422 In the House of Representatives, U. S., November 1, 2017. Whereas the People’s Republic of China assumed the exercise of sovereignty over the Hong Kong Special Administra- tive Region 20 years ago, on July 1, 1997; Whereas the Joint Declaration between the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and the Govern- ment of the People’s Republic of China on the Question of the Hong Kong (in this resolution referred to as the ‘‘Joint Declaration’’) required China’s National People’s Congress (NPC) to pass the ‘‘Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Re- public of China’’ (in this resolution referred to as the ‘‘Basic Law’’) consistent with the obligations contained in the Joint Declaration, which was approved by the NPC on April 4, 1990; Whereas relations between the United States and Hong Kong are fundamentally based upon the continued maintenance of the ‘‘one country, two systems’’ policy stipulated in the United States-Hong Kong Policy Act of 1992 (Public Law 102–383; 22 U.S.C. 5701 et seq.) and established by the Joint Declaration; Whereas under the ‘‘one country, two systems’’ policy estab- lished by the Joint Declaration, Hong Kong ‘‘will enjoy a high degree of autonomy except in foreign and defense 2 affairs’’ and ‘‘will be vested with executive, legislative and independent judicial power including that of final adju- dication’’; Whereas Hong Kong’s autonomy under the ‘‘one country, two systems’’ policy, as demonstrated by its highly developed rule of law, independent judiciary,