20190514154404876 18-280 Amicus Brief.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Big Business and Conservative Groups Helped Bolster the Sedition Caucus’ Coffers During the Second Fundraising Quarter of 2021

Big Business And Conservative Groups Helped Bolster The Sedition Caucus’ Coffers During The Second Fundraising Quarter Of 2021 Executive Summary During the 2nd Quarter Of 2021, 25 major PACs tied to corporations, right wing Members of Congress and industry trade associations gave over $1.5 million to members of the Congressional Sedition Caucus, the 147 lawmakers who voted to object to certifying the 2020 presidential election. This includes: • $140,000 Given By The American Crystal Sugar Company PAC To Members Of The Caucus. • $120,000 Given By Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy’s Majority Committee PAC To Members Of The Caucus • $41,000 Given By The Space Exploration Technologies Corp. PAC – the PAC affiliated with Elon Musk’s SpaceX company. Also among the top PACs are Lockheed Martin, General Dynamics, and the National Association of Realtors. Duke Energy and Boeing are also on this list despite these entity’s public declarations in January aimed at their customers and shareholders that were pausing all donations for a period of time, including those to members that voted against certifying the election. The leaders, companies and trade groups associated with these PACs should have to answer for their support of lawmakers whose votes that fueled the violence and sedition we saw on January 6. The Sedition Caucus Includes The 147 Lawmakers Who Voted To Object To Certifying The 2020 Presidential Election, Including 8 Senators And 139 Representatives. [The New York Times, 01/07/21] July 2021: Top 25 PACs That Contributed To The Sedition Caucus Gave Them Over $1.5 Million The Top 25 PACs That Contributed To Members Of The Sedition Caucus Gave Them Over $1.5 Million During The Second Quarter Of 2021. -

CDIR-2018-10-29-VA.Pdf

276 Congressional Directory VIRGINIA VIRGINIA (Population 2010, 8,001,024) SENATORS MARK R. WARNER, Democrat, of Alexandria, VA; born in Indianapolis, IN, December 15, 1954; son of Robert and Marge Warner of Vernon, CT; education: B.A., political science, George Washington University, 1977; J.D., Harvard Law School, 1980; professional: Governor, Commonwealth of Virginia, 2002–06; chairman of the National Governor’s Association, 2004– 05; religion: Presbyterian; wife: Lisa Collis; children: Madison, Gillian, and Eliza; committees: Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs; Budget; Finance; Rules and Administration; Select Com- mittee on Intelligence; elected to the U.S. Senate on November 4, 2008; reelected to the U.S. Senate on November 4, 2014. Office Listings http://warner.senate.gov 475 Russell Senate Office Building, Washington, DC 20510 .................................................. (202) 224–2023 Chief of Staff.—Mike Harney. Legislative Director.—Elizabeth Falcone. Communications Director.—Rachel Cohen. Press Secretary.—Nelly Decker. Scheduler.—Andrea Friedhoff. 8000 Towers Crescent Drive, Suite 200, Vienna, VA 22182 ................................................... (703) 442–0670 FAX: 442–0408 180 West Main Street, Abingdon, VA 24210 ............................................................................ (276) 628–8158 FAX: 628–1036 101 West Main Street, Suite 7771, Norfolk, VA 23510 ........................................................... (757) 441–3079 FAX: 441–6250 919 East Main Street, Richmond, VA 23219 ........................................................................... -

Congress of the United States

Congress of the United States Washington, DC 20510 June 16, 2020 Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street SW Washington, D.C. 20554 Dear Commissioners: On behalf of our constituents, we write to thank you for the Federal Communications Commission’s (Commission’s) efforts during the COVID-19 pandemic. The work the Commission has done, including the Keep Americans Connected pledge and the COVID-19 Telehealth Program, are important steps to address the need for connectivity as people are now required to learn, work, and access healthcare remotely. In addition to these efforts, we urge you to continue the important, ongoing work to close the digital divide through all means available, including by finalizing rules to enable the nationwide use of television white spaces (TVWS). The COVID-19 pandemic has illuminated the consequences of the remaining digital divide: many Americans in urban, suburban, and rural areas still lack access to a reliable internet connection when they need it most. Even before the pandemic broadband access challenges have put many of our constituents at a disadvantage for education, work, and healthcare. Stay-at-home orders and enforced social distancing intensify both the problems they face and the need for cost- effective broadband delivery models. The unique characteristics of TVWS spectrum make this technology an important tool for bridging the digital divide. It allows for better coverage with signals traveling further, penetrating trees and mountains better than other spectrum bands. Under your leadership, the FCC has taken significant bipartisan steps toward enabling the nationwide deployment of TVWS, including by unanimously adopting the February 2020 notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM), which makes several proposals that we support. -

May 11, 2020 the Honorable Elaine L. Chao Secretary of the Department of Transportation U.S. Department of Transportation 1200 N

May 11, 2020 The Honorable Elaine L. Chao Secretary of the Department of Transportation U.S. Department of Transportation 1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20590 Dear Secretary Chao, We write to bring your attention to the Port of Virginia's application to the 2020 Port Infrastructure Development Discretionary Grants Program to increase on-terminal rail capacity at their Norfolk International Terminals (NIT) facility in Norfolk, Virginia. If awarded, the funds will help increase safety, improve efficiency, and increase the reliability of the movement of goods. We ask for your full and fair consideration. The Port of Virginia is one of the Commonwealth's most powerful economic engines. On an annual basis, the Port is responsible for nearly 400,000 jobs and $92 billion in spending across our Commonwealth and generates 7.5% of our Gross State Product. The Port of Virginia serves as a catalyst for commerce throughout the Commonwealth of Virginia and beyond. To expand its commercial impact, the Port seeks to use this funding to optimize its central rail yard at NIT. The Port's arrival and departure of cargo by rails is the largest of any port on the East Coast, and the proposed optimization will involve the construction of two new rail bundles containing four tracks each for a total of more than 10,000 additional feet of working track. This project will improve efficiency, allow more cargo to move through the facility, improve the safety of operation, remove more trucks from the highways, and generate additional economic development throughout the region. The Port of Virginia is the only U.S. -

2017 Official General Election Results

STATE OF ALABAMA Canvass of Results for the Special General Election held on December 12, 2017 Pursuant to Chapter 12 of Title 17 of the Code of Alabama, 1975, we, the undersigned, hereby certify that the results of the Special General Election for the office of United States Senator and for proposed constitutional amendments held in Alabama on Tuesday, December 12, 2017, were opened and counted by us and that the results so tabulated are recorded on the following pages with an appendix, organized by county, recording the write-in votes cast as certified by each applicable county for the office of United States Senator. In Testimony Whereby, I have hereunto set my hand and affixed the Great and Principal Seal of the State of Alabama at the State Capitol, in the City of Montgomery, on this the 28th day of December,· the year 2017. Steve Marshall Attorney General John Merrill °\ Secretary of State Special General Election Results December 12, 2017 U.S. Senate Geneva Amendment Lamar, Amendment #1 Lamar, Amendment #2 (Act 2017-313) (Act 2017-334) (Act 2017-339) Doug Jones (D) Roy Moore (R) Write-In Yes No Yes No Yes No Total 673,896 651,972 22,852 3,290 3,146 2,116 1,052 843 2,388 Autauga 5,615 8,762 253 Baldwin 22,261 38,566 1,703 Barbour 3,716 2,702 41 Bibb 1,567 3,599 66 Blount 2,408 11,631 180 Bullock 2,715 656 7 Butler 2,915 2,758 41 Calhoun 12,331 15,238 429 Chambers 4,257 3,312 67 Cherokee 1,529 4,006 109 Chilton 2,306 7,563 132 Choctaw 2,277 1,949 17 Clarke 4,363 3,995 43 Clay 990 2,589 19 Cleburne 600 2,468 30 Coffee 3,730 8,063 -

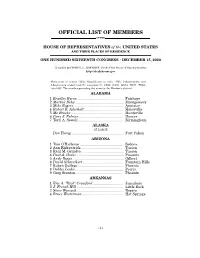

Official List of Members

OFFICIAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES of the UNITED STATES AND THEIR PLACES OF RESIDENCE ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS • DECEMBER 15, 2020 Compiled by CHERYL L. JOHNSON, Clerk of the House of Representatives http://clerk.house.gov Democrats in roman (233); Republicans in italic (195); Independents and Libertarians underlined (2); vacancies (5) CA08, CA50, GA14, NC11, TX04; total 435. The number preceding the name is the Member's district. ALABAMA 1 Bradley Byrne .............................................. Fairhope 2 Martha Roby ................................................ Montgomery 3 Mike Rogers ................................................. Anniston 4 Robert B. Aderholt ....................................... Haleyville 5 Mo Brooks .................................................... Huntsville 6 Gary J. Palmer ............................................ Hoover 7 Terri A. Sewell ............................................. Birmingham ALASKA AT LARGE Don Young .................................................... Fort Yukon ARIZONA 1 Tom O'Halleran ........................................... Sedona 2 Ann Kirkpatrick .......................................... Tucson 3 Raúl M. Grijalva .......................................... Tucson 4 Paul A. Gosar ............................................... Prescott 5 Andy Biggs ................................................... Gilbert 6 David Schweikert ........................................ Fountain Hills 7 Ruben Gallego ............................................ -

HR 4438 Don't Tax Higher Education

17 Elk Street 518-436-4781 www.cicu.org Albany, NY 12207 518-436-0417 fax www.nycolleges.org [email protected] Office of the President October 11, 2019 The Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Honorable Kevin McCarthy Speaker Minority Leader U.S. House of Representatives U.S. House of Representatives The Honorable Bobby Scott The Honorable Virginia Foxx Chairman Ranking Member Committee on Education and Labor Committee on Education and Labor U.S. House of Representatives U.S. House of Representatives The Honorable Brendan Boyle The Honorable Bradley Byrne Pennsylvania’s 2nd District Alabama’s 1st District U.S. House of Representatives U.S. House of Representatives Dear Speaker Pelosi, Minority Leader McCarthy, Chairman Scott and Ranking Member Foxx, Congressman Boyle, and Congressman Byrne: On behalf of the 100+ private, not-for-profit colleges in New York State, I write to you today in support of the H.R. 4438 Don’t Tax Higher Education Act, sponsored by Representatives Boyle and Byrne. This legislation would repeal the excise tax on investment income of private colleges and universities. Under current law, certain private colleges and universities are subject to a 1.4 percent excise tax on net investment income. This provision applies to private colleges and universities that have endowment assets of $500,000 per Full Time Equivalent (FTE) student. State colleges and universities are not subject to this provision even though many enjoy very strong endowments. H.R. 4438 would correct the ill-conceived decision to tax higher education that was made in 2017. Endowments are used prudently to support the higher education mission of an institution, and a tax on them invariably lessens what can be spent on students and on providing access to a high-quality education. -

3268 HON. CHIP CRAVAACK HON. MIKE Mcintyre HON. H

3268 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS, Vol. 158, Pt. 3 March 8, 2012 service to, a free and democratic Cuba. Her the ability to give individualized attention to HONORING DR. BARBARA DAVIS work began with the International Rescue each one of its students with a 15:1 student to Committee (IRC), the first agency in Miami to faculty ratio. HON. ANN MARIE BUERKLE provide assistance to thousands of Cuban ref- UNC Pembroke has achieved national rec- OF NEW YORK ugees fleeing Castro’s communist regime, and ognition for its diversity as well as its strong IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES the State Department of Public Welfare— ties with the community. U.S. News and World Cuban Refugee Emergency Center. Sylvia Thursday, March 8, 2012 Report has deemed the University ‘‘the most continues fighting relentlessly for Cuba’s free- Ms. BUERKLE. Mr. Speaker, I rise today to diverse University in the South,’’ the Princeton dom today, as a co-founder of M.A.R. por recognize Dr. Barbara Davis for 25 years of Cuba (Mothers & Women Against Oppres- Review has named UNC Pembroke among service to the Hebrew Day School in Syra- sion), and the Assembly of the Cuban Resist- the ‘‘Best in the Southeast,’’ and the University cuse, New York. ance. This organization is committed to the was named to President Obama’s Community Dr. Davis earned her Bachelor’s Degree defense of human rights and freedoms of Service Honor Roll for three consecutive from Barnard College and received an M.A. Cuban people, the support of Cuban political years. Additionally, the Carnegie Foundation and Ph.D. -

July 8, 2020 President Donald J. Trump the White House 1600

July 8, 2020 President Donald J. Trump The White House 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20500 Dear Mr. President: Thank you for your leadership as our country recovers from the economic fallout resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, including by signing bipartisan legislation, like the Paycheck Protection Program Flexibility Act, into law. You listened to the concerns of small business employers about the negative impacts posed by the failure to fully reopen the economy and the barriers to effectively rehiring employees created by enhanced government unemployment benefits. As negotiations on further federal legislative actions begin, we write to urge you to firmly oppose any extension of the $600 supplemental unemployment insurance (UI) enacted in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. Future legislation should only include policies that encourage businesses to reopen and hire employees. In fact, extending the $600 supplemental UI payments will only slow our economic recovery. According to the Congressional Budget Office, extending the supplemental UI program through the end of the year would result in approximately five of every six recipients receiving benefits that exceed their expected earnings when they return to work. It should be a fundamental principle that government benefits should not pay Americans more than if they went to work. The result is no surprise: CBO determined extending this program would result in higher unemployment in both 2020 and 2021. Small businesses are facing unprecedented challenges caused by COVID-19 and the resulting lockdowns enacted by state and local governments. There could not be a worse time for the federal government to create disincentives for returning to work. -

115Th Congress 281

VIRGINIA 115th Congress 281 NJ, 1990; Ph.D., in economics, American University, Washington, DC, 1995; family: wife, Laura; children: Jonathan and Sophia; committees: Budget; Education and the Workforce; Small Business; elected to the 114th Congress on November 4, 2014; reelected to the 115th Congress on November 8, 2016. Office Listings http://www.brat.house.gov facebook: representativedavebrat twitter: @repdavebrat 1628 Longworth House Office Building, Washington, DC 20515 ........................................... (202) 225–2815 Chief of Staff.—Mark Kelly. FAX: 225–0011 Scheduler.—Grace Walt. ¨ Legislative Director.—Zoe O’Herin. Press Secretary.—Julianna Heerschap. 4201 Dominion Boulevard, Suite 110, Glen Allen, VA 23060 ................................................ (804) 747–4073 9104 Courthouse Road, Room 249, Spotsylvania, VA 22553 .................................................. (540) 507–7216 Counties: AMELIA, CHESTERFIELD (part), CULPEPER, GOOCHLAND, HENRICO (part), LOUISA, NOTTOWAY, ORANGE, POWHATAN, AND SPOTSYLVANIA (part). Population (2010), 727,366. ZIP Codes: 20106, 20186, 22407–08, 22433, 22508, 22534, 22542, 22551, 22553, 22565, 22567, 22580, 22701, 22713– 14, 22718, 22724, 22726, 22729, 22733–37, 22740–41, 22923, 22942, 22947, 22957, 22960, 22972, 22974, 23002, 23015, 23024, 23038–39, 23058–60, 23063, 23065, 23067, 23083–84, 23093, 23102–03, 23112–14, 23117, 23120, 23129, 23139, 23146, 23153, 23160, 23222, 23224–30, 23233–38, 23294, 23297, 23824, 23832–33, 23838, 23850, 23922, 23930, 23955, 23966 *** EIGHTH DISTRICT DONALD S. BEYER, JR., Democrat, of Alexandria, VA; born in the Free Territory of Tri- este, June 20, 1950; education: B.A., Williams College, MA, 1972; professional: Ambassador to Switzerland and Liechtenstein 2009–13; 36th Lieutenant Governor of Virginia, 1990–98; co- founder of the Northern Virginia Technology Council; former chair of Jobs for Virginia Grad- uates; served on Board of the D.C. -

Congressional Pictorial Directory.Indb I 5/16/11 10:19 AM Compiled Under the Direction of the Joint Committee on Printing Gregg Harper, Chairman

S. Prt. 112-1 One Hundred Twelfth Congress Congressional Pictorial Directory 2011 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 2011 congressional pictorial directory.indb I 5/16/11 10:19 AM Compiled Under the Direction of the Joint Committee on Printing Gregg Harper, Chairman For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Offi ce Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800; Fax: (202) 512-2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402-0001 ISBN 978-0-16-087912-8 online version: www.fdsys.gov congressional pictorial directory.indb II 5/16/11 10:19 AM Contents Photographs of: Page President Barack H. Obama ................... V Vice President Joseph R. Biden, Jr. .............VII Speaker of the House John A. Boehner ......... IX President pro tempore of the Senate Daniel K. Inouye .......................... XI Photographs of: Senate and House Leadership ............XII-XIII Senate Officers and Officials ............. XIV-XVI House Officers and Officials ............XVII-XVIII Capitol Officials ........................... XIX Members (by State/District no.) ............ 1-152 Delegates and Resident Commissioner .... 153-154 State Delegations ........................ 155-177 Party Division ............................... 178 Alphabetical lists of: Senators ............................. 181-184 Representatives ....................... 185-197 Delegates and Resident Commissioner ........ 198 Closing date for compilation of the Pictorial Directory was March 4, 2011. * House terms not consecutive. † Also served previous Senate terms. †† Four-year term, elected 2008. congressional pictorial directory.indb III 5/16/11 10:19 AM congressional pictorial directory.indb IV 5/16/11 10:19 AM Barack H. Obama President of the United States congressional pictorial directory.indb V 5/16/11 10:20 AM congressional pictorial directory.indb VI 5/16/11 10:20 AM Joseph R. -

Congressional Directory ALABAMA

2 Congressional Directory ALABAMA ALABAMA (Population 2010, 4,779,736) SENATORS RICHARD C. SHELBY, Republican, of Tuscaloosa, AL; born in Birmingham, AL, May 6, 1934; education: attended the public schools; B.A., University of Alabama, 1957; LL.B., University of Alabama School of Law, 1963; professional: attorney; admitted to the Alabama bar in 1961 and commenced practice in Tuscaloosa; member, Alabama State Senate, 1970–78; law clerk, Supreme Court of Alabama, 1961–62; city prosecutor, Tuscaloosa, 1963–71; U.S. Magistrate, Northern District of Alabama, 1966–70; special assistant Attorney General, State of Alabama, 1969–71; chairman, legislative council of the Alabama Legislature, 1977–78; former president, Tuscaloosa County Mental Health Association; member of Alabama Code Revision Committee, 1971–75; member: Phi Alpha Delta legal fraternity, Tuscaloosa County; Alabama and American bar associations; First Presbyterian Church of Tuscaloosa; Exchange Club; American Judicature Society; Alabama Law Institute; married: the former Annette Nevin in 1960; children: Richard C., Jr., and Claude Nevin; committees: chair, Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs; Appropriations; Rules and Administration; elected to the 96th Congress on No- vember 7, 1978; reelected to the three succeeding Congresses; elected to the U.S. Senate on November 4, 1986; reelected to each succeeding Senate term. Office Listings http://shelby.senate.gov twitter: @senshelby 304 Russell Senate Office Building, Washington, DC 20510 .................................................. (202) 224–5744 Chief of Staff.—Alan Hanson. FAX: 224–3416 Personal Secretary / Appointments.—Anne Caldwell. Communications Director.—Torrie Miller. The Federal Building, 1118 Greensboro Avenue, #240, Tuscaloosa, AL 35401 ..................... (205) 759–5047 Vance Federal Building, Room 321, 1800 5th Avenue North, Birmingham, AL 35203 .......