Rupee Devaluation and Economy of Sri Lanka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Economics and Politics of China's Exchange Rate Adjustment

ISA S Insight No. 88 – Date: 28 December 2009 469A Bukit Timah Road #07-01, Tower Block, Singapore 259770 Tel: 6516 6179 / 6516 4239 Fax: 6776 7505 / 6314 5447 Email: [email protected] Website: www.isas.nus.edu.sg The Economics and Politics of China’s Exchange Rate Adjustment M. Shahidul Islam1 Abstract China faces significant political pressure from industrialised economies to revalue its currency upward. Internally, China’s currency adjustment depends largely on the dynamics of its labour and financial markets. Millions of underutilised Chinese labourers, who are in the process of migration from the countryside to urban areas, give Beijing the upper hand in allowing a gradual revaluation of its currency. However, the growing cost of monetary sterilisation is the key hurdle in keeping its currency undervalued for long. Nevertheless, exchange rates are not always determined by economic forces alone – the breakdown of the Bretton Woods exchange rate system in 1971 and the signing of the Plaza Accord in 1985 are two examples. The available data shows that South Asia is generally not hurt, if not a gainer, by an undervalued Chinese currency. Introduction Vladimir Lenin, the leader of the erstwhile Soviet Union, is said to have declared that the best way to destroy the capitalist system was to debauch its currency.2 China abandoned the “communist way of development” long ago and it is indeed in Beijing’s interest to endure the capitalist system. Nevertheless, its exchange rate policy is literally annihilating the global capitalist system with the exception of its own. Beijing faces much pressure from almost all the industrialised economies to allow its currency to appreciate as they believe that the undervalued Chinese currency is eroding their export competitiveness. -

Currency Symbol for Indian Rupee Design Philosophy

Currency Symbol for Indian Rupee Design Philosophy The design philosophy of the symbol is derived from the Devanagari script, a traditional script deeply rooted in our Indian culture. The symbol also seamlessly integrates the Latin script which is widely used around the world. This amalgamation traverses boundaries across cultures giving it a universal identity, at the same time symbolizing our cultural values and ethos at a global platform. Simplicity of the visual form and imagery creates a deep impact on the minds of the people. And makes it easy to recognize, recall and represent by all age groups, societies, religions and cultures. Direct communication The symbol is designed using the Devanagari letter ‘Ra’ and Roman capital letter ‘R’. The letters are derived from the word Rupiah in Hindi and Rupees in English both denote the currency of India. The derivation of letters from these words conveys the association of the symbol with currency rupee. The symbol straightforwardly communicates the message of currency for both Indian and foreign nationals. In other words, a direct relationship is established between the symbol and the rupee. Shiro Rekha The use of Shiro Rekha (the horizontal top line) in Devanagari script is unique to India. Devanagari script is the only script where letters hang from the top line and does not sit on a baseline. The symbol preserves this unique and essential feature of our Indian script which is not seen in any other scripts in the world. It also clearly distinguishes itself from other symbols and establishes a sign of Indian origin. It explicitly states the Indianess of the symbol. -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: 3 8 147 - LK PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A Public Disclosure Authorized PROPOSED CREDIT IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 21.7 MILLION (US$32 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA FOR A PUTTALAM HOUSING PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized JANUARY 24,2007 Sustainable Development South Asia Region Public Disclosure Authorized This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective December 13,2006) Currency Unit = Sri Lankan Rupee 108 Rupees (Rs.) = US$1 US$1.50609 = SDR 1 FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ADB Asian Development Bank LTF Land Task Force AG Auditor General LTTE Liberation Tigers ofTamil Eelam CAS Country Assistance Strategy NCB National Competitive Bidding CEB Ceylon Electricity Board NGO Non Governmental Organization CFAA Country Financial Accountability Assessment NEIAP North East Irrigated Agriculture Project CQS Selection Cased on Consultants Qualifications NEHRP North East Housing Reconstruction Program CSIA Continuous Social Impact Assessment NPA National Procurement Agency CSP Camp Social Profile NPV Not Present Value CWSSP Community Water Supply and Sanitation NWPEA North Western Provincial Environmental Act Project DMC District Monitoring Committees NWPRD NorthWest Provincial Roads Department -

Expolanka Holdings Plc Integrated Annual Report

EXPOLANKA HOLDINGS PLC INTEGRATED ANNUAL REPORT 2020/21 EXPOLANKA HOLDINGS PLC | INTEGRATED REPORT 2020/21 2 fruitionEXPOLANKA HOLDINGS PLC | INTEGRATED ANNUAL REPORT 2020/21 At Expolanka, we remain fully committed to our promise made several years ago, to drive long term sustainable value, by adapting a focused, constant and consistent strategy. Even though the year under review post several challenges, we were able to pursue our said strategies and bring to fruition our plans for progress which was fueled by our innate resilience and strength. The seeds we planted have taken root and we keep our focus upward, expanding in our focused direction in order to adapt to the current environment. We remain fruitful in our optimism, our can-do attitude and endurance, a recipe for success that will carry us through to more opportunity. Overview EXPOLANKA HOLDINGS PLC | INTEGRATED ANNUAL REPORT 2020/21 2 CONTENTS Chairman’s Overview Compliance Reports 12 About Us 3 Corporate Governance 71 Message About this Report 4 Risk Management Report 93 Group Milestones 5 Related Party Transactions Financial Highlights 6 Review Committee Report 101 15 Group CEO’s Highlights of the Year 7 Remuneration Committee Report 103 Review Chairman’s Message 12 Group CEO’s Review 15 Financial Reports Board of Directors 18 Annual Report of the Board of Directors Group Senior Management Team 20 on the Affairs of the Company 108 23 Financial Indicators 22 The Statement of Directors’ Responsibility 112 Performance Group Performance 23 Audit Committee Report 113 Overcoming -

Rupee Strengthening to Be Short Lived

EQUITY | EXCHANGE RATE EVENT UPDATE |19 APR 2021 FLASHNOTE |09 MAY 2019 RUPEE STRENGTHENING TO BE SHORT LIVED BUY ON WEAKNESS [HAYL, HAYC, DIPD, MGT, TJL, EXPO] EVENT UPDATE Rupee appreciates with CDB loan: Sri Lankan Rupee appreciated FIRST CAPITAL RESEARCH 5.0% against the US Dollar over the last 2 market days reversing the Atchuthan Srirangan +94 11 263 9863 continuous accelerated depreciation witnessed in Jan-Apr 2021. On [email protected] 12th Apr LKR recorded a historical low of LKR 201:1 USD. Ministry of Finance (MoF) reported on 12th Apr that Govt of Sri Lanka entered LKR appreciates 5.0% into a loan agreement with the China Development Bank (CDB) for USD 500Mn and MoF expected the funds to be disbursed during the 203.0 same week. Following the announcement, the market registered a th steep appreciation with mid-rate today (19 ) recording at LKR 190.9. 200.0 Reserves fall to lowest since 2009: Sri Lanka’s Foreign reserves dropped to USD 4.1Bn in Mar 2021, the lowest since Aug 2009, on 197.0 the back of over USD 4.0Bn outstanding debt payment during Apr- Dec 2021 period. The total foreign debt repayment (capital and 194.0 interest) for 2021 was USD 6.0Bn. USD:LKR Rupee appreciation likely to be short-lived: Considering Sri Lanka’s 191.0 depleting foreign reserve position, high foreign currency debt repayment requirement and limited funding sources available in the 188.0 market is expected to further increase depreciation pressure for the currency during 2Q and 3Q. We maintain our exchange rate target for 1H2021 at LKR 196.0-202.0 with 2021 year-end target at LKR 185.0 205.0-215.0 as mentioned in our “Investment Strategy 2021 – Jan 2021”. -

Currency Codes COP Colombian Peso KWD Kuwaiti Dinar RON Romanian Leu

Global Wire is an available payment method for the currencies listed below. This list is subject to change at any time. Currency Codes COP Colombian Peso KWD Kuwaiti Dinar RON Romanian Leu ALL Albanian Lek KMF Comoros Franc KGS Kyrgyzstan Som RUB Russian Ruble DZD Algerian Dinar CDF Congolese Franc LAK Laos Kip RWF Rwandan Franc AMD Armenian Dram CRC Costa Rican Colon LSL Lesotho Malati WST Samoan Tala AOA Angola Kwanza HRK Croatian Kuna LBP Lebanese Pound STD Sao Tomean Dobra AUD Australian Dollar CZK Czech Koruna LT L Lithuanian Litas SAR Saudi Riyal AWG Arubian Florin DKK Danish Krone MKD Macedonia Denar RSD Serbian Dinar AZN Azerbaijan Manat DJF Djibouti Franc MOP Macau Pataca SCR Seychelles Rupee BSD Bahamian Dollar DOP Dominican Peso MGA Madagascar Ariary SLL Sierra Leonean Leone BHD Bahraini Dinar XCD Eastern Caribbean Dollar MWK Malawi Kwacha SGD Singapore Dollar BDT Bangladesh Taka EGP Egyptian Pound MVR Maldives Rufi yaa SBD Solomon Islands Dollar BBD Barbados Dollar EUR EMU Euro MRO Mauritanian Olguiya ZAR South African Rand BYR Belarus Ruble ERN Eritrea Nakfa MUR Mauritius Rupee SRD Suriname Dollar BZD Belize Dollar ETB Ethiopia Birr MXN Mexican Peso SEK Swedish Krona BMD Bermudian Dollar FJD Fiji Dollar MDL Maldavian Lieu SZL Swaziland Lilangeni BTN Bhutan Ngultram GMD Gambian Dalasi MNT Mongolian Tugrik CHF Swiss Franc BOB Bolivian Boliviano GEL Georgian Lari MAD Moroccan Dirham LKR Sri Lankan Rupee BAM Bosnia & Herzagovina GHS Ghanian Cedi MZN Mozambique Metical TWD Taiwan New Dollar BWP Botswana Pula GTQ Guatemalan Quetzal -

Exchange Rate PAMPHLET SERIES NO

Exchange Rate PAMPHLET SERIES NO. 3 EXCHANGEFinancial System RATE Stability The pamphlet explains what the exchange rate is, why it is important and the factors that determine it. It also touches upon exchange rate appreciation and depreciation and the significance of nominal and real effective exchange rates. It describes the spectrum of different types of exchange rate regimes ranging from the fixed exchange rate system to the floating exchange rate system and traces the history of the evolution of exchange rate regimes in Sri Lanka since Independence. It also provides an overview of the foreign exchange market and the role of the Central Bank in maintaining exchange rate stability. Central Bank of Sri Lanka April 2006 Pamphlet Series No. 3 1 Exchange Rate 1. EXCHANGE RATE Most countries use their own currencies as a In the foreign exchange markets, the former medium of exchange, similar to the Rupee in Sri expression is more widely used. For instance, if Lanka and the Dollar in the United States. They the exchange rate of the US dollar for the Sri are deemed to be the legal tender or legally valid Lankan rupee is Rs.100, that means that a to make all local payments. However, a few person who wants to buy one US dollar would countries have adopted currencies of other need to pay one hundred Sri Lankan rupees in countries as legal tender. An example of such a exchange for one US dollar. In other words, one country is Liberia, which uses the US dollar as Sri Lankan rupee is worth US dollars 0.01 at the legal tender. -

Crown Agents Bank's Currency Capabilities

Crown Agents Bank’s Currency Capabilities August 2020 Country Currency Code Foreign Exchange RTGS ACH Mobile Payments E/M/F Majors Australia Australian Dollar AUD ✓ ✓ - - M Canada Canadian Dollar CAD ✓ ✓ - - M Denmark Danish Krone DKK ✓ ✓ - - M Europe European Euro EUR ✓ ✓ - - M Japan Japanese Yen JPY ✓ ✓ - - M New Zealand New Zealand Dollar NZD ✓ ✓ - - M Norway Norwegian Krone NOK ✓ ✓ - - M Singapore Singapore Dollar SGD ✓ ✓ - - E Sweden Swedish Krona SEK ✓ ✓ - - M Switzerland Swiss Franc CHF ✓ ✓ - - M United Kingdom British Pound GBP ✓ ✓ - - M United States United States Dollar USD ✓ ✓ - - M Africa Angola Angolan Kwanza AOA ✓* - - - F Benin West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Botswana Botswana Pula BWP ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Burkina Faso West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Cameroon Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F C.A.R. Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Chad Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Cote D’Ivoire West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ F DR Congo Congolese Franc CDF ✓ - - ✓ F Congo (Republic) Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Egypt Egyptian Pound EGP ✓ ✓ - - F Equatorial Guinea Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Eswatini Swazi Lilangeni SZL ✓ ✓ - - F Ethiopia Ethiopian Birr ETB ✓ ✓ N/A - F 1 Country Currency Code Foreign Exchange RTGS ACH Mobile Payments E/M/F Africa Gabon Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Gambia Gambian Dalasi GMD ✓ - - - F Ghana Ghanaian Cedi GHS ✓ ✓ - ✓ F Guinea Guinean Franc GNF ✓ - ✓ - F Guinea-Bissau West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ - - F Kenya Kenyan Shilling KES ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ F Lesotho Lesotho Loti LSL ✓ ✓ - - E Liberia Liberian -

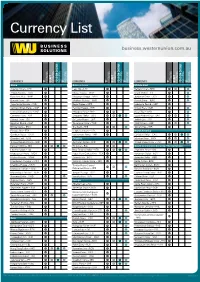

View Currency List

Currency List business.westernunion.com.au CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING Africa Asia continued Middle East Algerian Dinar – DZD Laos Kip – LAK Bahrain Dinar – BHD Angola Kwanza – AOA Macau Pataca – MOP Israeli Shekel – ILS Botswana Pula – BWP Malaysian Ringgit – MYR Jordanian Dinar – JOD Burundi Franc – BIF Maldives Rufiyaa – MVR Kuwaiti Dinar – KWD Cape Verde Escudo – CVE Nepal Rupee – NPR Lebanese Pound – LBP Central African States – XOF Pakistan Rupee – PKR Omani Rial – OMR Central African States – XAF Philippine Peso – PHP Qatari Rial – QAR Comoros Franc – KMF Singapore Dollar – SGD Saudi Arabian Riyal – SAR Djibouti Franc – DJF Sri Lanka Rupee – LKR Turkish Lira – TRY Egyptian Pound – EGP Taiwanese Dollar – TWD UAE Dirham – AED Eritrea Nakfa – ERN Thai Baht – THB Yemeni Rial – YER Ethiopia Birr – ETB Uzbekistan Sum – UZS North America Gambian Dalasi – GMD Vietnamese Dong – VND Canadian Dollar – CAD Ghanian Cedi – GHS Oceania Mexican Peso – MXN Guinea Republic Franc – GNF Australian Dollar – AUD United States Dollar – USD Kenyan Shilling – KES Fiji Dollar – FJD South and Central America, The Caribbean Lesotho Malati – LSL New Zealand Dollar – NZD Argentine Peso – ARS Madagascar Ariary – MGA Papua New Guinea Kina – PGK Bahamian Dollar – BSD Malawi Kwacha – MWK Samoan Tala – WST Barbados Dollar – BBD Mauritanian Ouguiya – MRO Solomon Islands Dollar – -

Remittance Economy Migration-Underdevelopment in Sri Lanka

REMITTANCE ECONOMY MIGRATION-UNDERDEVELOPMENT IN SRI LANKA Matt Withers A thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Department of Political Economy The University of Sydney 2017 “Ceylon ate the fruit before growing the tree” - Joan Robinson (Wilson 1977) (Parren as 2005) (Eelens and Speckmann 1992) (Aneez 2016b) (International Monetary Fund (IMF) 1993; International Monetary Fund (IMF) 2009) (Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) 2004) (United Nations Population Division 2009) Acknowledgements Thanks are due to a great number of people who have offered support and lent guidance throughout the course of my research. I would like to extend my appreciation foremost to my wonderful supervisors, Elizabeth Hill and Stuart Rosewarne, whose encouragement and criticism have been (in equal measure) invaluable in shaping this thesis. I must similarly offer heartfelt thanks to my academic mentors, Nicola Piper and Janaka Biyanwila, both of whom have unfailingly offered their time, interest and wisdom as my work has progressed. Gratitude is also reserved for my colleagues Magdalena Cubas and Rosie Hancock, who have readily guided me through the more challenging stages of thesis writing with insights and lessons from their own research. A special mention must be made for the Centre for Poverty Analysis in Colombo, without whose assistance my research would simply not have been possible. I would like to thank Priyanthi Fernando for her willingness to accommodate me, Mohamed Munas for helping to make fieldwork arrangements, and to Vagisha Gunasekara for her friendship and willingness to answer my incessant questions about Sri Lanka. -

A Survey on Volatility Fluctuations in the Decentralized Cryptocurrency Financial Assets

Journal of Risk and Financial Management Review A Survey on Volatility Fluctuations in the Decentralized Cryptocurrency Financial Assets Nikolaos A. Kyriazis Department of Economics, University of Thessaly, 38333 Volos, Greece; [email protected] Abstract: This study is an integrated survey of GARCH methodologies applications on 67 empirical papers that focus on cryptocurrencies. More sophisticated GARCH models are found to better explain the fluctuations in the volatility of cryptocurrencies. The main characteristics and the optimal approaches for modeling returns and volatility of cryptocurrencies are under scrutiny. Moreover, emphasis is placed on interconnectedness and hedging and/or diversifying abilities, measurement of profit-making and risk, efficiency and herding behavior. This leads to fruitful results and sheds light on a broad spectrum of aspects. In-depth analysis is provided of the speculative character of digital currencies and the possibility of improvement of the risk–return trade-off in investors’ portfolios. Overall, it is found that the inclusion of Bitcoin in portfolios with conventional assets could significantly improve the risk–return trade-off of investors’ decisions. Results on whether Bitcoin resembles gold are split. The same is true about whether Bitcoins volatility presents larger reactions to positive or negative shocks. Cryptocurrency markets are found not to be efficient. This study provides a roadmap for researchers and investors as well as authorities. Keywords: decentralized cryptocurrency; Bitcoin; survey; volatility modelling Citation: Kyriazis, Nikolaos A. 2021. A Survey on Volatility Fluctuations in the Decentralized Cryptocurrency Financial Assets. Journal of Risk and 1. Introduction Financial Management 14: 293. The continuing evolution of cryptocurrency markets and exchanges during the last few https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm years has aroused sparkling interest amid academic researchers, monetary policymakers, 14070293 regulators, investors and the financial press. -

6 Production Details of Organic Tea Estates in Sri Lanka

Status of organic agriculture in Sri Lanka with special emphasis on tea production systems (Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze) Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades „Doktor der Agrarwissenschaften“ am Fachbereich Pflanzenbau der Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen PhD Thesis Faculty of Plant Production, Justus-Liebig-University of Giessen vorgelegt von / submitted by Ute Williges OCTOBER 2004 Acknowledgement The author gratefully acknowledges the financial assistance received from the German Academic Exchange Service (Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst, DAAD) for the field work in Sri Lanka over a peroid of two years and the „Hochschul- und Wissenschaftsprogramm (HWP)“ for supporting the compilation of the thesis afterwards in Germany. My sincere thanks goes to my teacher Prof. Dr. J. Sauerborn whose continuous supervision and companionship accompanied me throughout this work and period of live. Further I want to thank Prof. Dr. Wegener and Prof. Dr. Leithold for their support regarding parts of the thesis and Dr. Hollenhorst for his advice carrying out the statistical analysis. My appreciation goes to Dr. Nanadasena and Dr. Mohotti for their generous provision of laboratory facilities in Sri Lanka. My special thanks goes to Mr. Ekanayeke whose thoughts have given me a good insight view in tea cultivation. I want to mention that parts of the study were carried out in co-operation with the Non Governmental Organisation Gami Seva Sevana, Galaha, Bio Foods (Pvt) Ltd., Bowalawatta, the Tea Research Institute (TRI) of Sri Lanka, Talawakele; The Tea Small Holders Development Authority (TSHDA), Regional Extension Centre, Sooriyagoda; The Post Graduate Institute of Agriculture (PGIA), Department of Soil Science, University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya and The Natural Resources Management Services (NRMS), Mahaweli Authority of Sri Lanka, Polgolla.