276286936.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emergence of an Information Infrastructure Through Integrating Waste Drug Recycling, Medication Management, and Household Drug Management in China

Proceedings of the 52nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences | 2019 Emergence of an Information Infrastructure through Integrating Waste Drug Recycling, Medication Management, and Household Drug Management in China Yumei Luo Kai Reimers College of Business and Tourism Management, School of Business and Economics Yunnan University RWTH Aachen University [email protected] [email protected] Abstract In China, storing drugs for emergent use in homes in large quantities and varieties has become a common The total amount of waste drugs is expanding practice. With the rapid economic and social significantly as populations age and societies become development of society the total amount of household wealthier. Drug waste is becoming a problem for waste drugs is expanding significantly. In 2014, a health and environment. Thus, how to reduce and survey showed that about 78.6% of families in China effectively dispose of waste drugs is increasingly have the habit of storing prescription medicine and becoming an issue for society. In this paper, we more than 80% of the families do not regularly purge analyze the current situation with regard to existing their stock from expired medicines and even fewer systems for expired drug recycling and disposal in people know how to properly dispose of the expired China and suggest that by connecting the involved medicine [7]. The survey also showed that 72.5% of practices of waste drug recycling, medication families throw expired drugs into regular household management, and household drug management the waste, 5% flush them down the toilet or drain, and 6% incentives to participate in an integrated drug of families even continue to use them. -

Safe Disposal of Unused Controlled Substances

Safe Disposal of Unused Controlled Substances/ Current Challenges and Opportunities for Reform Prepared for: King Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Prepared by: Sharon Siler Suzanne Duda Ruth Brown Josette Gbemudu Scott Weier Jon Glaudemans King Pharmaceuticals, Inc. provided funding for this research. Avalere Health maintained full editorial control and the conclusions expressed here are those of the authors. TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 14 METHODOLOGY 18 CURRENT LANDSCAPE FOR DRUG DISPOSAL PROGRAMS 32 CRITICAL SUCCESS FACTORS 52 MODELS FOR REFORM 60 CONCLUSION 62 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 64 ENDNOTES King Pharmaceuticals, Inc. provided funding for this research. Avalere Health maintained full editorial control and the conclusions expressed here are those of the authors. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SAFE DISPOSAL OF UNUSED CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES Disposal of unused prescription drugs, and controlled substances in particular, is a complicated issue. Unused drug take-back programs are emerging across the country as one strategy for reducing drug abuse, accidental poison- ing, and flushing drugs into the water supply. Current laws and regulations regarding controlled substances, however, limit these programs from accepting all drugs without strict oversight from law enforcement. SIGNIFICANT BARRIERS The Controlled Substances Act and Drug Enforcement Agency regulations dictate who can handle controlled substances, and are two of the most significant challenges today facing efforts to dispose of unused drugs. The law and regulations prohibit pharmacies, providers, and hospitals from collecting controlled substances that have already been dispensed to consumers. There is an exception that allows law enforcement officers to accept controlled substances, but because of the added burden of en- suring a law enforcement presence at take-back events, most programs are not currently accepting controlled substances from consumers. -

Enviroshopping1 Marie Hammer and Joan Papadi2

Archival copy: for current recommendations see http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu or your local extension office. Fact Sheet HE 3167 Enviroshopping1 Marie Hammer and Joan Papadi2 You have tremendous influence in the board fossil-based fuels can also degrade the environment, rooms of American companies. They listen each time such as oil spills occurring in the ocean. And the you open your wallet. They will listen when you say production of fossil-based fuels affects the ‘‘Reduce, Reuse, Recycle.’’ They will listen when you environment, as when coal is strip-mined. ‘‘Reject and Respond.’’ As an enviroshopper, consider the environment when you compare the convenience, Hydro-electric power is not without its the cost and the quality of your purchases. You will environmental effects. To create the power source, feel proud that you did ‘‘the right thing’’ for yourself thousands of acres of land are dammed up and and future generations. flooded. As a result, the river ecology and wildlife habitat are destroyed. Nuclear power, too, produces Grains of sand make mighty sand dunes, and bits radio-active waste for which we have not yet found a of trash make mountains of garbage. In Florida we solution. throw away about eight pounds of garbage per person each day. The national average is about 3.5 pounds Most people are aware of the environmental per day. The Florida rate is increased somewhat by damage possible when disposing of waste by landfill the trash from our visitors (about 35 million each or burning. Few people realize that creating a product year). such as packaging from raw materials causes more environmental damage than disposing of it. -

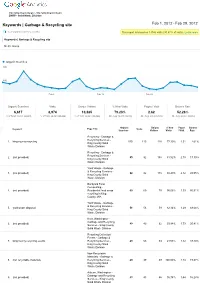

Keywords | Garbage & Recycling Site

http://www.kingcounty.gov http://www.kingcounty.gov DNRP Solid Waste Division Keywords | Garbage & Recycling site Feb 1, 2012 Feb 29, 2012 % of organic searches: 23.23% This report is based on 13346 visits (30.47% of visits). Learn more Keywords | Garbage & Recycling site Metric Group Organic Searches 800 400 Feb 8 Feb 15 Feb 22 Organic Searches Visits Unique Visitors % New Visits Pages / Visit Bounce Rate 6,617 8,974 10,385 79.23% 2.62 52.26% % of Total: 23.23% (28,481) % of Total: 20.49% (43,806) % of Total: 28.56% (36,365) Site Avg: 76.47% (3.61%) Site Avg: 2.95 (11.18%) Site Avg: 50.55% (3.39%) Organic Unique % New Pages Bounce Keyword Page Title Visits Searches Visitors Visits / Visit Rate Recycling Garbage & Recycling Services 1. king county recycling 115 115 128 77.39% 1.51 2.61% King County Solid Waste Division Recycling Garbage & Recycling Services 2. (not provided) 85 92 158 81.52% 2.78 17.39% King County Solid Waste Division Yard Waste Garbage & Recycling Services 3. (not provided) 82 82 118 80.49% 2.12 28.05% King County Solid Waste Division Backyard Food Composting 4. (not provided) Residential food scrap 69 69 79 95.65% 1.33 85.51% recycling in King County, WA Yard Waste Garbage & Recycling Services 5. yard waste disposal 56 56 59 82.14% 1.29 69.64% King County Solid Waste Division Kent, Washington Garbage and Recycling 6. (not provided) 49 49 62 93.88% 1.73 20.41% Services King County Solid Waste Division Recycling Collection Events Garbage & 7. -

Talking Trash: Oral Histories of Food In/Security from the Margins of a Dumpster By: Rachel A

Talking Trash: Oral Histories of Food In/Security from the Margins of a Dumpster By: Rachel A. Vaughn Submitted to the graduate degree program in American Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson, Dr. Sherrie Tucker ________________________________ Dr Tanya Hart ________________________________ Dr. Sheyda Jahanbani ______________________________ Dr. Phaedra Pezzullo ________________________________ Dr. Ann Schofield Date Defended: Friday, December 2, 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Rachel A. Vaughn certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Talking Trash: Oral Histories of Food In/Security from the Margins of a Dumpster ________________________________ Chairperson, Dr. Sherrie Tucker Date approved: December, 2, 2011 ii Abstract This dissertation explores oral histories with dumpster divers of varying food security levels. The project draws from 15 oral history interviews selected from an 18-interview collection conducted between Spring 2008 and Summer 2010. Interviewees self-identified as divers; varied in economic, gender, sexual, and ethnic identity; and ranged in age from 18-64 years. To supplement this modest number of interviews, I also conducted 52 surveys in Summer 2010. I interview divers as theorists in their own right, and engage the specific ways in which the divers identify and construct their food choice actions in terms of individual food security and broader ecological implications of trash both as a food source and as an international residue of production, trade, consumption, and waste policy. This research raises inquiries into the gender, racial, and class dynamics of food policy, informal food economies, common pool resource usage, and embodied histories of public health and sanitation. -

SYMBIOSIS the Journal of Ecologically Sustainable Medicine

SYMBIOSIS The Journal of Ecologically Sustainable Medicine THE TELEOSIS INSTITUTE Vol. 4 No. 2 Spring/Summer 2007 In This Issue Letter from the Director Health News: Pharmaceutical Pollution Green Pharmacy Pharmaceutical Pollution: Ecology and Toxicology Christian Daughton and the Ecology of PPCPs Water Quality in the 21st Century The 4 Ts—Assessing Exposure to Multiple Chemicals Green Pharmacy: Preventing Pollution A Cross Sector Approach Ecological Economics and the Drug Life Cycle Unused and Expired Medicines Pollution Prevention Partners Spotlight on Green Pharmacy Website Review Book Review www.teleosis.org SYMBIOSIS Board of Directors George Brandt Treasurer, San Francisco, CA Wendy Buffet, MD Secretary, San Francisco, CA Sean Esbjorn-Hargens, PhD Sebastopol, CA Calista Hunter, MD San Ramon, CA Joel Kreisberg, DC Chairman, Berkeley, CA Advisory Board Bhaswati Bhattacharya, MD Director of Research Department of Medicine, Wyckoff Heights Medical Center Daniel Callahan, PhD Director of International Program, The Hastings Center Larry Dossey, MD Executive Editor, Explore: Journal of Science and Healing Gil Friend, MS President and CEO, Natural Logic, Inc. Constance Grauds, RPh President, Association of Natural Medicine Pharmacists Ben Kligler, MD Integrative Medicine, Continuum Center for Health and Healing, Beth Israel Hospital Lee Klinger, PhD Independent Scientist, The Sudden Oak Life Task Force Tara Levy, ND President, California Naturopathic Doctors Association David Orr, PhD Chair of the Environmental Studies Program, Oberlin -

Minutes Riley County Solid Waste Management Committee

MINUTES RILEY COUNTY SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE Thursday, March 1, 2018 Riley County Office Building 7:00 P.M. 2nd Floor Conference Room Members Present: Steve Galitzer, Leon Hobson, David Kreller, Perry Piper, Casey Smithson, William Spiegel, Monty Wedel, Ron Wells and Fran Zerby Others Present: Gary Rosewicz and Karen McCulloh Members Absent: Betty Book, William Clark, Dennis Peterson, Charly Pottorf, Dave Shover, Judy Willingham and Howard Wilson. Steve Galitzer, Chairman, called the meeting to order. Sign-in, Introductions The sign-in sheet and introductions were completed. Approve the minutes of the previous meeting David Kreller moved and William Spiegel seconded to approve the minutes of the March 2, 2017 meeting as presented. Motion approved. Update on Solid Waste budget Gary Rosewicz presented the attached “2018 Solid Waste Advisory Board Report”. He said with projected revenues and expenditures he doesn’t recommend any increases to the current rates for 2018. He did indicate that this is barring any unforeseen major expenditures but will still have to overlay the roadway and area around the station. Mr. Rosewicz did state that eventually the crane will have to be replaced. David Kreller asked if KDHE requires the county to have a reserve or bond. Gary Rosewicz replied the county is not required to have a reserve or bond but the county does have an insurance policy. He also said the Hamm’s contract will be expiring in 2020. These contracts in the past have been written to automatically annually renew for a 10 year period which helps to keep the bid costs lower. -

REPORT Date: AUGUST 17, 2021

CITY OF WARRENVILLE MEMO To: Members of the Environmental Advisory Commission From: David Romero, Civil Engineer Subject: AUGUST 2021 STAFF REPORT Date: AUGUST 17, 2021 DuPage County Environmental Committee The following things were discussed at the August 3rd meeting of the DuPage Environmental Committee. Attached are the summary of minutes. • The proposed budget for FY 2022 Environmental Programs was presented. • An Extended Producer Responsibility program for packaging and paper products was discussed. This Lake County initiative seeks to put the onus for recycling of paper packaging on manufacturers and not consumers. Pursuit of legislation as early as 2022 is envisioned. Consensus support for the concept and proposal was given by the Committee. Electric Aggregation Program (Administration) The City entered into a new electric aggregation agreement that includes $24,155 in civic contributions back to the City. The Council suggested staff work with the EAC on the following: 1) Evaluate the benefits of Renewable Energy Certificates versus Civic Contributions to assist with future recommendations. 2) Assist with recommendations for how best to use the civic contributions for “green” initiatives or programs in the community. Staff has proposed the following projects as options: - Update Cantera streetlights with LED fittings - Add solar panels to a wellhouse - Add solar panels to the trailhead building - Purchase rain barrels to give away as part of a drawing Attached find the memo from Assistant City Administrator White discussing the program. Groot Composting Update (Administration) Assistant City Administrator White confirmed details regarding the Groot composting service. Residents can compost food scraps only if they are subscribed for the yard waste service cart. -

Buy Smarter1 Marie Hammer and Joan Papadi2

Archival copy: for current recommendations see http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu or your local extension office. FCS3158 Enviroshopping: Buy Smarter1 Marie Hammer and Joan Papadi2 Each week, a ritual called "taking out the the products are manufactured, stored, and garbage" is repeated in nearly every household. In transported to the retail store, pollution can occur. neatly tied-up trash bags are the unwanted Each incident of pollution may be small, but added fragments of our daily lives. Once deposited at together they contribute to the pollution problems curbside or in a dumpster, the garbage (technically that are of so much concern today. By reducing the called solid waste) is picked up, hauled to a landfill amount of waste you produce, you save energy and for disposal and forgotten by those who generated reduce pollution. it. Packing with a Purpose Floridians throw away about 8 pounds of garbage per person each day, double the national There are a number of ways to tackle the average. The Florida rate is increased somewhat by problem of garbage. One way starts with you and the trash from our visitors (35 million a year) and the products you buy. You can shop with the an active construction industry which generates a environment in mind. Try to buy products that: large amount of debris. ! make the best use of energy resources; All this garbage is "Here Today...Here Tomorrow." We must be responsible not only for ! don't pollute our air and water; what we consume, but also for what we dispose. What we dispose of wastes energy and materials ! are reusable or recyclable; and can release pollutants into the environment. -

Pharmaceuticals in Water

Pharmaceuticals in Water An Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the faculty of Worcester Polytechnic Institute In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science By Cody Beckel, Chris Garceau, Andrew Miggels Advisor: John Bergendahl 1 Table of Contents i) Introduction……………………………………………………………………..2 ii) Background……………………………………………………………………..2 (a) History…………………………………………………………………..5 (b) Studies…………………………………………………………………..6 (c) Water Treatment Plants………………………………………………...12 (d) Legislation…………………………………………………………...…15 iii) Methodology…………………………………………………………………...19 iv) Results………………………………………………………………………….22 (a) How are pharmaceuticals being discharged……………………………22 (b) Which pharmaceuticals are being discharged and found………………25 (c) Effects…………………………………………………………………..31 (d) Bacteria Resistance……………………………………………………..32 (e) Treatment Plants and how they work…………………………………..34 (f) Which treatments are effective…………………………………………40 (g) Worcester TP and Hospital……………………………………………..45 v) Solutions………………………………………………………………………..52 (aa) Legislation………………………………………………………….52 (bb) Disposal solutions……………………………...…………………..54 (cc) Awareness………………………………………………………….60 2 I. Introduction Even with all of today‟s water treatment methods, there are still large amounts of chemicals in what is referred to as “clean” water. This is an ever growing problem especially with the amount of pharmaceutical compounds found in water. For the past twenty-five years there have been various attempts to determine the concentration of pharmaceutical compounds in drinking water (Webb et al., 2003). This problem was first brought to light in the 1990‟s in Europe when pharmaceutical compounds were found not only in drinking water but in greater abundance in wastewaters, streams, and ground-water resources across Europe. Though pharmaceutical compounds had been found in landfills and sewage-treatment plants these new discoveries showed that some of these compounds are getting into the water and then are not treated in the water treatment plants. -

Green Pharmaceutical Supply Chain in UK

Abstract Number: 015-0318 Green Community Pharmaceutical Supply Chain in UK: Reducing and Recycling Pharmaceutical Waste Ying Xie*, Liz Breen** *Business School, University of Greenwich, Maritime Campus, London, SE10 9LS UK, Email: [email protected], Tel: +44 (0)20 83317956 ** Bradford University School of Management Emm Lane, Bradford, West Yorkshire BD9 4JL UK, Email: [email protected] POMS 21st Annual Conference Vancouver, Canada May 7 to May 10, 2010 Abstract The Pharmaceutical Supply Chain (PSC) is a SC where pharmaceutical medications are produced, transported and consumed. Disposal of the medication waste is harmful to the environment and costly, therefore, greening the PSC by properly managing the medication waste is investigated. A Cross Boundary Green PSC (XGPSC) approach is proposed to design a green PSC that results in fewer preventable medication waste and more recycling of inevitable medication waste, therefore improved environmental, economic and safety performances. This study focuses on the community PSC in UK where patients get medication from local community pharmacies. To green the PSC, every producer of waste is duty bound to ensure the safe handling and disposal of waste. This duty of care spans throughout the chain and includes all participants. This approach is drawn from the contemporary literature and our collaborative research, and can be used as a guidance to establish a waste management network in community PSC. Keywords: Green supply chain, pharmaceutical supply chain, environmental practices 1. Introduction There has been increased consciousness of the environment in the last few decades. More people realise the world‟s environmental issues such as global warming, carbon emissions, toxic substance usage, and resources scarcity. -

Download the PDF Version

2 iGEM 2019 - Giant Jamboree iGEM 2019 - Giant Jamboree 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS About ............................................................................................... 6 Contributors ..................................................................................... 7 Sponsors .......................................................................................... 11 Exhibitors ........................................................................................ 12 Maps ............................................................................................... 13 Plaza Level ............................................................................ 13 Halls C and D .......................................................................... 14 Second Floor .......................................................................... 15 Third Floor ............................................................................. 16 Schedule .......................................................................................... 17 Thursday ................................................................................. 18 Friday ..................................................................................... 20 Saturday ................................................................................. 22 Workshops ........................................................................................ 24 Handbook ......................................................................................... 35 4 iGEM 2019