Investigating the Decline of the African Lion Population in Lake Nakuru National Park Using Diet Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dalmatian Pelican Identification Manual Companion Document to the “Dalmatian Pelican Monitoring Manual”

Pelican Way of LIFE (LIFE18 NAT/NL/716) “Conservation of the Dalmatian Pelican along the Black Sea - Mediterranean Flyway” Dalmatian Pelican Identification Manual Companion document to the “Dalmatian Pelican Monitoring Manual” December 2020 Authored by: Commissioned by: Giorgos Catsadorakis and Olga Alexandrou, Society for the Protection of Prespa Rewilding Europe Dalmatian Pelican Identification Manual - Companion document to the “Dalmatian Pelican Monitoring Manual” December 2020 Authors: Giorgos Catsadorakis1 and Olga Alexandrou2 1,2Society for the Protection of Prespa, Agios Germanos, GR-53150, Prespa, Greece, [email protected] , [email protected] © Rewilding Europe Executed under the framework of “Conservation of the Dalmatian Pelican along the Black Sea - Mediterranean Flyway” (Pelican Way of LIFE; LIFE18 NAT/NL/716; https://life-pelicans.com/) project, financed by the LIFE programme of the European Union and Arcadia – a charitable fund of Lisbet Rausing and Peter Baldwin. Suggested citation: Society for the Protection of Prespa, 2020. Dalmatian pelican identification manual - Companion document to the “Dalmatian pelican monitoring manual”. Rewilding Europe. Produced within the framework of Pelican Way of LIFE project (LIFE18 NAT/NL/716). Keywords: Dalmatian pelican, identification, ageing, plumage, moulting patterns, sexing. Photo credits: Society for the Protection of Prespa, unless stated otherwise. Introduction Visual identification of the Dalmatian pelican seems like a straightforward task, yet in sites used by both species (the Dalmatian pelican and the great white pelican) identification can be tricky, especially when the observer is located some distance away from the birds. Hardly any useful material has been published on the sequence of moults and plumages of the Dalmatian pelican, and this gap often creates confusion and uncertainty about the accuracy of data in regards to ageing of Dalmatian pelicans, as well as frequently undermining confidence in census numbers. -

The Gambia: a Taste of Africa, November 2017

Tropical Birding - Trip Report The Gambia: A Taste of Africa, November 2017 A Tropical Birding “Chilled” SET DEPARTURE tour The Gambia A Taste of Africa Just Six Hours Away From The UK November 2017 TOUR LEADERS: Alan Davies and Iain Campbell Report by Alan Davies Photos by Iain Campbell Egyptian Plover. The main target for most people on the tour www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] p.1 Tropical Birding - Trip Report The Gambia: A Taste of Africa, November 2017 Red-throated Bee-eaters We arrived in the capital of The Gambia, Banjul, early evening just as the light was fading. Our flight in from the UK was delayed so no time for any real birding on this first day of our “Chilled Birding Tour”. Our local guide Tijan and our ground crew met us at the airport. We piled into Tijan’s well used minibus as Little Swifts and Yellow-billed Kites flew above us. A short drive took us to our lovely small boutique hotel complete with pool and lovely private gardens, we were going to enjoy staying here. Having settled in we all met up for a pre-dinner drink in the warmth of an African evening. The food was delicious, and we chatted excitedly about the birds that lay ahead on this nine- day trip to The Gambia, the first time in West Africa for all our guests. At first light we were exploring the gardens of the hotel and enjoying the warmth after leaving the chilly UK behind. Both Red-eyed and Laughing Doves were easy to see and a flash of colour announced the arrival of our first Beautiful Sunbird, this tiny gem certainly lived up to its name! A bird flew in landing in a fig tree and again our jaws dropped, a Yellow-crowned Gonolek what a beauty! Shocking red below, black above with a daffodil yellow crown, we were loving Gambian birds already. -

Encyclopaedia of Birds for © Designed by B4U Publishing, Member of Albatros Media Group, 2020

✹ Tomáš Tůma Tomáš ✹ ✹ We all know that there are many birds in the sky, but did you know that there is a similar Encyclopaedia vast number on our planet’s surface? The bird kingdom is weird, wonderful, vivid ✹ of Birds and fascinating. This encyclopaedia will introduce you to over a hundred of the for Young Readers world’s best-known birds, as well as giving you a clear idea of the orders in which birds ✹ ✹ are classified. You will find an attractive selection of birds of prey, parrots, penguins, songbirds and aquatic birds from practically every corner of Planet Earth. The magnificent full-colour illustrations and easy-to-read text make this book a handy guide that every pre- schooler and young schoolchild will enjoy. Tomáš Tůma www.b4upublishing.com Readers Young Encyclopaedia of Birds for © Designed by B4U Publishing, member of Albatros Media Group, 2020. ean + isbn Two pairs of toes, one turned forward, ✹ Toco toucan ✹ Chestnut-eared aracari ✹ Emerald toucanet the other back, are a clear indication that Piciformes spend most of their time in the trees. The beaks of toucans and aracaris The diet of the chestnut-eared The emerald toucanet lives in grow to a remarkable size. Yet aracari consists mainly of the fruit of the mountain forests of South We climb Woodpeckers hold themselves against tree-trunks these beaks are so light, they are no tropical trees. It is found in the forest America, making its nest in the using their firm tail feathers. Also characteristic impediment to the birds’ deft flight lowlands of Amazonia and in the hollow of a tree. -

Kenyan Birding & Animal Safari Organized by Detroit Audubon and Silent Fliers of Kenya July 8Th to July 23Rd, 2019

Kenyan Birding & Animal Safari Organized by Detroit Audubon and Silent Fliers of Kenya July 8th to July 23rd, 2019 Kenya is a global biodiversity “hotspot”; however, it is not only famous for extraordinary viewing of charismatic megafauna (like elephants, lions, rhinos, hippos, cheetahs, leopards, giraffes, etc.), but it is also world-renowned as a bird watcher’s paradise. Located in the Rift Valley of East Africa, Kenya hosts 1054 species of birds--60% of the entire African birdlife--which are distributed in the most varied of habitats, ranging from tropical savannah and dry volcanic- shaped valleys to freshwater and brackish lakes to montane and rain forests. When added to the amazing bird life, the beauty of the volcanic and lava- sculpted landscapes in combination with the incredible concentration of iconic megafauna, the experience is truly breathtaking--that the Africa of movies (“Out of Africa”), books (“Born Free”) and documentaries (“For the Love of Elephants”) is right here in East Africa’s Great Rift Valley with its unparalleled diversity of iconic wildlife and equatorially-located ecosystems. Kenya is truly the destination of choice for the birdwatcher and naturalist. Karibu (“Welcome to”) Kenya! 1 Itinerary: Day 1: Arrival in Nairobi. Our guide will meet you at the airport and transfer you to your hotel. Overnight stay in Nairobi. Day 2: After an early breakfast, we will embark on a full day exploration of Nairobi National Park--Kenya’s first National Park. This “urban park,” located adjacent to one of Africa’s most populous cities, allows for the possibility of seeing the following species of birds; Olivaceous and Willow Warbler, African Water Rail, Wood Sandpiper, Great Egret, Red-backed and Lesser Grey Shrike, Rosy-breasted and Pangani Longclaw, Yellow-crowned Bishop, Jackson’s Widowbird, Saddle-billed Stork, Cardinal Quelea, Black-crowned Night- heron, Martial Eagle and several species of Cisticolas, in addition to many other unique species. -

The Status and Distribution of Spot-Billed Pelican Pelecanus Philippensis in Southern India

FORKTAIL 21 (2005): 9–14 The status and distribution of Spot-billed Pelican Pelecanus philippensis in southern India V. KANNAN and RANJIT MANAKADAN Surveys for Spot-billed Pelican Pelecanus philippensis were conducted in southern India from May 2000 to April 2004. Population estimates were based on counts of birds at nesting colonies and of large congregations at foraging sites, supplemented by published and unpublished recent records. A population of 2,850–3,700 birds is estimated for the states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Kerala, which is higher than earlier estimates. INTRODUCTION used in the analysis. In some cases the survey data were supplemented with secondary information obtained Spot-billed Pelican Pelecanus philippensis is one of the from forest department records, local people and most threatened of the seven species of pelicans in the birdwatchers. All counts were carried out rapidly from world. The total population is estimated to number watchtowers, vehicles, or on foot, to reduce the 2,500–5,000 individuals in South Asia, 3,000–5,000 chances of double counting. Counts at foraging sites individuals in South-East Asia and <25 individuals in were generally carried out from 07h00 to 09h00, while Sumatra (BirdLife International 2001, Wetlands those at colonies were carried out between 11h00 and International 2002). Populations are declining owing 14h00 when most of the adults would have returned to factors such as human disturbance at the nesting from the foraging grounds. It was not always possible grounds, hunting, loss of wetlands, pollution and over- to count the number of nests owing to dense vegetation fishing (see BirdLife International 2001 and obstructing views. -

Conservation of Spot Billed Pelican in North Central and Central

id23306625 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com Conservation of Spot Billed Pelican in North Central and Central provinces of Sri Lanka Kanchana Weerakoon and Harsha Athukorala Eco Friendly Volunteers (ECO-V) Sri Lanka Conservation of Spot Billed Pelican in North Central and Central provinces of Sri Lanka Final Report of project Pelecanus 2003 Kanchana Weerakoon & Harsha Athukorala Eco Friendly Volunteers (ECO-V) 93/5 Jambugasmulla Mawatha, Nugegoda Sri Lanka Email: [email protected] Tel: 0094112 646361 Web: www.eco-v.org With the Support of: Project Pelecanus 2003 ________________________________________________________________________ Table of Contents ________________________________________________________________________ i Executive Summery 5 ii Conclusions and Recommendations 7 ii Organisational Profile - Eco Friendly Volunteers (ECO-V) 8 iv Acknowledgements 10 v Abbreviations 12 1 Introduction 13 2 Objectives 18 3 Methodology 19 4 Study Area 22 5 Results 25 6 Discussion 35 7 References 42 8 Budget 45 Executive Summery (English) Spot-billed Pelican became a candidate for the IUCN Red Data list in 1988 and it is the second pelican of the world to become threatened. The Known breeding populations of SBP are now confined to India (c.2000 birds) Sri Lanka (500-3000 birds) and Cambodia (more than 5000 birds around Tonle Sap Lake). However the situation of Spot-billed Pelicans in Sri Lanka is more poorly documented. There were no systematic studies carried out in Sri Lanka on this globally threatened bird species. The present study is the first ever systematic field study and awareness programme carried out on the Spot Billed Pelicans in Sri Lanka. -

Presence of the Peruvian Pelican Pelecanus Thagus in Seabird Colonies of Chilean Patagonia

Cursach et al.: Peruvian Pelican in Chilean Patagonia 27 PRESENCE OF THE PERUVIAN PELICAN PELECANUS THAGUS IN SEABIRD COLONIES OF CHILEAN PATAGONIA JAIME A. CURSACH1,2,3, JAIME R. RAU2 & JONNATHAN VILUGRÓN2 1Programa de Doctorado en Ciencias mención Conservación y Manejo de Recursos Naturales, Universidad de Los Lagos, casilla 557, Puerto Montt, Chile ([email protected]) 2Laboratorio de Ecología, Departamento de Ciencias Biológicas y Biodiversidad, Universidad de Los Lagos, casilla 933, Osorno, Chile 3Laboratorio de Investigación Socioambiental, Programa ATLAS, Departamento de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de Los Lagos, casilla 933, Osorno, Chile Received 30 July 2015, accepted 18 December 2015 SUMMARY Cursach, J.A., Rau, J.R. & Vilugrón, J. Presence of the Peruvian Pelican Pelicanus thagus in seabird colonies of Chilean Patagonia. Marine Ornithology 44: 27–30. Over the past few years, an increase in Peruvian Pelican Pelecanus thagus presence has occurred in southern Chile, along the coast of the Los Lagos region, at the southern end of its range. We evaluate the presence of the pelicans in seabird colonies of this region and describe their behavior and interactions with other seabird species. Three colonies were surveyed: San Pedro Bay Islets (40°55′S), Kaikué-Lagartija Island (41°48′S) and Caicura Island (41°42′S). Counts were carried out from boats, and age structure was determined based on plumage color. Pelicans were found to be numerous and included a high proportion of juveniles. With the exception of one pelican egg (unhatched) found at Caicura Island in December 2013, there was no evidence of pelican nesting. Potential competitive interactions between the pelicans and other seabirds were evident. -

Common Birds of Namibia and Botswana 1 Josh Engel

Common Birds of Namibia and Botswana 1 Josh Engel Photos: Josh Engel, [[email protected]] Integrative Research Center, Field Museum of Natural History and Tropical Birding Tours [www.tropicalbirding.com] Produced by: Tyana Wachter, R. Foster and J. Philipp, with the support of Connie Keller and the Mellon Foundation. © Science and Education, The Field Museum, Chicago, IL 60605 USA. [[email protected]] [fieldguides.fieldmuseum.org/guides] Rapid Color Guide #584 version 1 01/2015 1 Struthio camelus 2 Pelecanus onocrotalus 3 Phalacocorax capensis 4 Microcarbo coronatus STRUTHIONIDAE PELECANIDAE PHALACROCORACIDAE PHALACROCORACIDAE Ostrich Great white pelican Cape cormorant Crowned cormorant 5 Anhinga rufa 6 Ardea cinerea 7 Ardea goliath 8 Ardea pupurea ANIHINGIDAE ARDEIDAE ARDEIDAE ARDEIDAE African darter Grey heron Goliath heron Purple heron 9 Butorides striata 10 Scopus umbretta 11 Mycteria ibis 12 Leptoptilos crumentiferus ARDEIDAE SCOPIDAE CICONIIDAE CICONIIDAE Striated heron Hamerkop (nest) Yellow-billed stork Marabou stork 13 Bostrychia hagedash 14 Phoenicopterus roseus & P. minor 15 Phoenicopterus minor 16 Aviceda cuculoides THRESKIORNITHIDAE PHOENICOPTERIDAE PHOENICOPTERIDAE ACCIPITRIDAE Hadada ibis Greater and Lesser Flamingos Lesser Flamingo African cuckoo hawk Common Birds of Namibia and Botswana 2 Josh Engel Photos: Josh Engel, [[email protected]] Integrative Research Center, Field Museum of Natural History and Tropical Birding Tours [www.tropicalbirding.com] Produced by: Tyana Wachter, R. Foster and J. Philipp, -

South Africa: the Southwestern Cape & Kruger August 17–September 1, 2018

SOUTH AFRICA: THE SOUTHWESTERN CAPE & KRUGER AUGUST 17–SEPTEMBER 1, 2018 Leopard LEADER: PATRICK CARDWELL LIST COMPILED BY: PATRICK CARDWELL VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM SOUTH AFRICA: THE SOUTHWESTERN CAPE & KRUGER AUGUST 17–SEPTEMER 1, 2018 By Patrick Cardwell Our tour started in the historical gardens of the Alphen Hotel located in the heart of the Constantia Valley, with vineyards dating back to 1652 with the arrival of Jan van Riebeeck, the first Governor of the Cape. Surrounded by aging oak and poplar trees, this Heritage Site hotel is perfectly situated as a central point within the more rural environs of Cape Town, directly below the towering heights of Table Mountain and close to the internationally acclaimed botanical gardens of Kirstenbosch. DAY 1 A dramatic change in the prevailing weather pattern dictated a ‘switch’ between scheduled days in the itinerary to take advantage of a window of relatively calm sea conditions ahead of a cold front moving in across the Atlantic from the west. Our short drive to the harbor followed the old scenic road through the wine lands and over Constantia Nek to the picturesque and well-wooded valley of Hout (Wood) Bay, so named by the Dutch settlers for the abundance of old growth yellow wood trees that were heavily exploited during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Our skipper was on standby to welcome us on board a stable sport fishing boat with a wraparound gunnel, ideal for all-round pelagic seabird viewing and photographic opportunity in all directions. -

Kruger Comprehensive

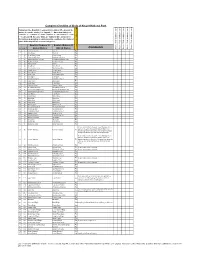

Complete Checklist of birds of Kruger National Park Status key: R = Resident; S = present in summer; W = present in winter; E = erratic visitor; V = Vagrant; ? - Uncertain status; n = nomadic; c = common; f = fairly common; u = uncommon; r = rare; l = localised. NB. Because birds are highly mobile and prone to fluctuations depending on environmental conditions, the status of some birds may fall into several categories English (Roberts 7) English (Roberts 6) Comments Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps # Rob # Global Names Old SA Names Rough Status of Bird in KNP 1 1 Common Ostrich Ostrich Ru 2 8 Little Grebe Dabchick Ru 3 49 Great White Pelican White Pelican Eu 4 50 Pinkbacked Pelican Pinkbacked Pelican Er 5 55 Whitebreasted Cormorant Whitebreasted Cormorant Ru 6 58 Reed Cormorant Reed Cormorant Rc 7 60 African Darter Darter Rc 8 62 Grey Heron Grey Heron Rc 9 63 Blackheaded Heron Blackheaded Heron Ru 10 64 Goliath Heron Goliath Heron Rf 11 65 Purple Heron Purple Heron Ru 12 66 Great Egret Great White Egret Rc 13 67 Little Egret Little Egret Rf 14 68 Yellowbilled Egret Yellowbilled Egret Er 15 69 Black Heron Black Egret Er 16 71 Cattle Egret Cattle Egret Ru 17 72 Squacco Heron Squacco Heron Ru 18 74 Greenbacked Heron Greenbacked Heron Rc 19 76 Blackcrowned Night-Heron Blackcrowned Night Heron Ru 20 77 Whitebacked Night-Heron Whitebacked Night Heron Ru 21 78 Little Bittern Little Bittern Eu 22 79 Dwarf Bittern Dwarf Bittern Sr 23 81 Hamerkop -

Wildlife Report

Singita Grumeti Sasakw a & Faru Faru Lodges Serengeti House & Sabora Tented Camp Explore Mobile Tented Camp Tanzania Wildlife Report For the month of July, Two Thousand and Fifteen Temperature & Wind Rainfall Recorded Sunrise & Sunset Average maximum 30.9 °C (87.6 °F) Sasakwa 63 mm Sunrise 06:47 Average minimum 16.4 °C (61.5 °F) Sabora 09 mm Sunset 18:48 Average wind speed 6 m/s Faru Faru 15 mm Samaki 03 mm Risiriba 45 mm Lions: As always we had good daily sightings of lions in July. Prides seen were the usual suspects: Sabora West pride, Ridge pride, and Butamtam pride. The Butamtam pride has extended its territory east to the Grumeti River, downstream of Faru Faru, but we are now left wondering where the Mkuyu pride, whose territory has always been this same area of the Grumeti River, moved to? Six of the Butamtam sub-adult males are now over two years old. It is only a matter of time that their dominant male father(s) kick them out of the pride... Leopard: Leopard sightings were steady this month, but the Tulia female and her two adorable cubs were not seen until the very end of the month. Cheetah: Excellent cheetah sightings this month. The most seen of these spotted cats were a female with two young cubs, a female with two eight-month old cubs, and two adult brothers. Wild Dogs: After some stellar sightings in June, the wild dogs were nowhere to be found in July. Word has it that they have been spending a lot of time in the Nyasirori area of the National Park, southwest of Sabora Camp. -

Program and Abstracts

The Waterbird Society 43rd Annual Meeting 6-9 November 2019 Princess Anne, Maryland Contents Welcome from the President of the Waterbird Society ......................................... 5 About the Waterbird Society ................................................................................ 6 Welcome from the Scientific Program Chair ........................................................ 7 Welcome from the Committee on Local Arrangements ....................................... 8 Transportation: SLUGGING IT ........................................................................... 9 Directions, hotel to UMES ................................................................................ 11 Day-by-day-schedule ........................................................................................ 14 Social events schedule ....................................................................................... 16 Special sessions ................................................................................................ 18 Atlantic Marine Bird Cooperative 2023 Atlantic and Gulf Coast coordinated colonial waterbird survey Wildlife Acoustics: Using Bioacoustics as a Valuable Waterbird Research Tool Scientific Program Information Instructions for talks .............................................................................. 19 Instructions for poster presentations ....................................................... 19 Plenary Speaker Biography .................................................................... 21 Symposia