Burial Practices in Northern England C. AD 650-850: A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ug Abuse and Dependence

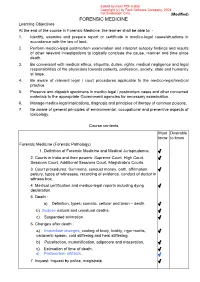

Edited by Foxit PDF Editor Copyright (c) by Foxit Software Company, 2004 For Evaluation Only. (Modified) FORENSIC MEDICINE Learning Objectives At the end of the course in Forensic Medicine, the learner shall be able to: - 1. Identify, examine and prepare report or certificate in medico-legal cases/situations in accordance with the law of land. 2. Perform medico-legal postmortem examination and interpret autopsy findings and results of other relevant investigations to logically conclude the cause, manner and time since death. 3. Be conversant with medical ethics, etiquette, duties, rights, medical negligence and legal responsibilities of the physicians towards patients, profession, society, state and humanity at large. 4. Be aware of relevant legal / court procedures applicable to the medico-legal/medical practice. 5. Preserve and dispatch specimens in medico-legal / postmortem cases and other concerned materials to the appropriate Government agencies for necessary examination. 6. Manage medico-legal implications, diagnosis and principles of therapy of common poisons. 7. Be aware of general principles of environmental, occupational and preventive aspects of toxicology. Course contents Must Desirable know to know Forensic Medicine (Forensic Pathology) 1. Definition of Forensic Medicine and Medical Jurisprudence. √ 2. Courts in India and their powers: Supreme Court, High Court, √ Sessions Court, Additional Sessions Court, Magistrate’s Courts. 3. Court procedures: Summons, conduct money, oath, affirmation, √ perjury, types of witnesses, recording of evidence, conduct of doctor in witness box, 4. Medical certification and medico-legal reports including dying √ declaration. 5. Death : a) Definition, types; somatic, cellular and brain – death. √ b) Sudden natural and unnatural deaths. √ c) Suspended animation. √ 6. -

Saxon Newsletter-Template.Indd

Saxon Newsletter of the Sutton Hoo Society No. 50 / January 2010 (© Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery) Hoards of Gold! The recovery of hundreds of 7th–8th century objects from a field in Staffordshire filled the newspapers when it was announced by the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) at a press conference on 24 September. Uncannily, the first piece of gold was recovered seventy years to the day after the first gold artefact was uncovered at Sutton Hoo on 21 July 1939.‘The old gods are speaking again,’ said Dr Kevin Leahy. Dr Leahy, who is national finds advisor on early medieval metalwork to the PAS and who catalogued the hoard, will be speaking to the SHS on 29 May (details, back page). Current Archaeology took the hoard to mark the who hate thee be driven from thy face’. (So even launch of their ‘new look’ when they ran ten pages this had a military flavour). of pictures in their November issue [CA 236] — “The art is like Sutton Hoo — gold with clois- which, incidentally, includes a two-page interview onée garnet and fabulous ‘Style 2’ animal interlace with our research director, Professor Martin on pommels and cheek guards — but maybe a Carver. bit later in date. This and the inscription suggest Martin tells us, “The hoard consists of 1,344 an early 8th century date overall — but this will items mainly of gold and silver, although 864 of probably move about. More than six hundred pho- these weigh less than 3g. The recognisable parts of tos of the objects can be seen on the PAS’s Flickr the hoard are dominated by military equipment — website. -

DOA Stories and Questions

Name:_________________ Hour:_______ Dead On Arrival Articles Getting Rid of the Body !Criminals don"t like to leave behind evidence, although they usually do. In a murder, the primary bit of evidence is obviously the body. Sometimes a murderer attempts to completely destroy the body of a victim, reasoning that no body means no conviction. Not true -- convictions have been obtained even when no body is found. Regardless, destroying a body is no easy task. Fire seems to be the favorite tool of murderers looking to cover their tracks, but its almost never successful. Short of a crematorium, creating a fire that burns hot enough and long enough to destroy a human corpse is nearly impossible. !Another favorite is quicklime, which murderers often have seen used in the movies. Knowing the chemistry behind it might make them think twice about this one. Quicklime is calcium oxide. When it contacts water, as it often does in burial sites, it reacts with the water to make calcium hydroxide, also known as slaked lime. This corrosive material may damage the surface of the corpse, but the heat produced from its activity kills many of the putrefying bacteria and dehydrates the body, thereby preventing decay and promoting mummification. Thus, the use of quicklime actually may help preserve the body. !Acids also are commonly used by ill-informed criminals hoping to dissolve the body, which is not only difficult but extremely hazardous. Acids that are powerful enough to dissolve a body exist, but they require a great deal of time to complete the task. -

Forensic Medicine and Toxicology

FORENSIC MEDICINE AND TOXICOLOGY CURRICULUM OF SYLLABUS UNDER THE NEW REGULATIONS FOR THE MBBS. COURSES OF STUDIES EFFECTIVE FROM THE SESSION: 2017-18 . 3RD SEMESTER: 1.INTRODUCTION (1hr) a. Definitions: forensic medicine, state medicine, legal medicine, medical jurisprudence, medical ethics, medical etiquette b. Various branches of forensic science. c. History and evolution of forensic medicine from ancient period to modern period 2.LEGAL PROCEDURE (2hr) a. Definition: bill, act, code, court, law, statutory law b. Major codes and acts: Indian Penal Code (IPC), Criminal Procedure Code (Cr.PC), Indian Evidence Act c. Different Courts of Law, their structure and functions: Supreme Court, High Court, Sessions Court, Judicial Magistrate Courts d. Offences: cognizable/non-cognizable, bailable/non-bailable, warrant case, summon case e. Different types of punishments authorized by law f. Inquest: definition, types and procedure of different inquests [police inquest, magistrate inquest (executive and judicial magistrate inquest), coroner’s inquest, medical examiner’s system] g. Summon: definition, types, salient features h. Conduct money i. Medical evidence: definition, types (documentary and oral), documentary evidence (defn, types of medical documentary evidences), special emphasis on ‘how to record dying declaration’, oral evidence (defn, exception to oral evidence), direct evidence, indirect evidence (circumstantial and hearsay) j. Chain of custody k. Witness: definition, types, hostile witness and perjury l. Procedure of recording of evidence in Court of law: starting from receiving a summon, oath taking, examination in chief, cross examination, re-examination, question by the Judge, checking the written form of oral evidence by the doctor, Court attendance certificate m. Conduct and duties of a doctor in witness box n. -

The Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Mercia and the Origins and Distribution of Common Fields*

The Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Mercia and the origins and distribution of common fields* by Susan Oosthuizen Abstract: This paper aims to explore the hypothesis that the agricultural layouts and organisation that had de- veloped into common fields by the high middle ages may have had their origins in the ‘long’ eighth century, between about 670 and 840 AD. It begins by reiterating the distinction between medieval open and common fields, and the problems that inhibit current explanations for their period of origin and distribution. The distribution of common fields is reviewed and the coincidence with the kingdom of Mercia noted. Evidence pointing towards an earlier date for the origin of fields is reviewed. Current views of Mercia in the ‘long’ eighth century are discussed and it is shown that the kingdom had both the cultural and economic vitality to implement far-reaching landscape organisation. The proposition that early forms of these field systems may have originated in the ‘long’ eighth century is considered, and the paper concludes with suggestions for further research. Open and common fields (a specialised form of open field) endured in the English landscape for over a thousand years and their physical remains still survive in many places. A great deal is known and understood about their distribution and physical appearance, about their man- agement from their peak in the thirteenth century through the changes of the later medieval and early modern periods, and about how and when they disappeared. Their origins, however, present a continuing problem partly, at least, because of the difficulties in extrapolating in- formation about such beginnings from documentary sources and upstanding earthworks that record – or fossilise – mature or even late field systems. -

A Denial the Death of Kurt Cobain the Seattle Police Department

A Denial The Death of Kurt Cobain The Seattle Police Department Substandard Investigation & The Repercussions to Justice by Bree Donovan A Capstone Submitted to The Graduate School-Camden Rutgers, The State University, New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Liberal Studies Under the direction of Dr. Joseph C. Schiavo and approved by _________________________________ Capstone Director _________________________________ Program Director Camden, New Jersey, December 2014 i Abstract Kurt Cobain (1967-1994) musician, artist songwriter, and founder of The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame band, Nirvana, was dubbed, “the voice of a generation”; a moniker he wore like his faded cardigan sweater, but with more than some distain. Cobain‟s journey to the top of the Billboard charts was much more Dickensian than many of the generations of fans may realize. During his all too short life, Cobain struggled with physical illness, poverty, undiagnosed depression, a broken family, and the crippling isolation and loneliness brought on by drug addiction. Cobain may have shunned the idea of fame and fortune but like many struggling young musicians (who would become his peers) coming up in the blue collar, working class suburbs of Aberdeen and Tacoma Washington State, being on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine wasn‟t a nightmare image. Cobain, with his unkempt blond hair, polarizing blue eyes, and fragile appearance is a modern-punk-rock Jesus; a model example of the modern-day hero. The musician- a reluctant hero at best, but one who took a dark, frightening journey into another realm, to emerge stronger, clearer headed and changing the trajectory of his life. -

Lawyer's Guide to Forensic Medicine

LAWYER’S GUIDE TO FORENSIC MEDICINE CP Cavendish Publishing Limited London • Sydney LAWYER’S GUIDE TO FORENSIC MEDICINE Second Edition Bernard Knight, CBE, MD, DSc (Hon), LLD (Hon), BCh, MRCP, FRCPath, Dip Med Jur Barrister of Gray’s Inn Emeritus Professor of Forensic Pathology, University of Wales College of Medicine CP Cavendish Publishing Limited London • Sydney Published in Great Britain 1998 by Cavendish Publishing Limited, The Glass House, Wharton Street, London WC1X 9PX, United Kingdom. Telephone: +44 (0) 171 278 8000 Facsimile: +44 (0) 171 278 8080 E-mail: [email protected] Visit our Home Page on http://www.cavendishpublishing.com First published by William Heinemann Medical Books 1982 © Knight, Bernard 1998 First edition 1982 Second edition 1998 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1P 9HE, UK, without the permission in writing of the publisher. Knight, Bernard Lawyer’s Guide to Forensic Medicine – 2nd edn 1. Medical jurisprudence I. Title 614.1 ISBN 1 85941 159 2 Printed and bound in Great Britain PREFACE The 16 years that have elapsed since the first edition of this book have seen many changes which require significant updating of the text. Some entries have been deleted and others added, to reflect the changing priorities in the interface between medicine and the law. -

The Demo Version

Æbucurnig Dynbær Edinburgh Coldingham c. 638 to Northumbria 8. England and Wales GODODDIN HOLY ISLAND Lindisfarne Tuidi Bebbanburg about 600 Old Melrose Ad Gefring Anglo-Saxon Kingdom NORTH CHANNEL of Northumbria BERNICIA STRATHCLYDE 633 under overlordship Buthcæster Corebricg Gyruum * of Northumbria æt Rægeheafde Mote of Mark Tyne Anglo-Saxon Kingdom Caerluel of Mercia Wear Luce Solway Firth Bay NORTHHYMBRA RICE Other Anglo-Saxon united about 604 Kingdoms Streonæshalch RHEGED Tese Cetreht British kingdoms MANAW Hefresham c 624–33 to Northumbria Rye MYRCNA Tribes DEIRA Ilecliue Eoforwic NORTH IRISH Aire Rippel ELMET Ouse SEA SEA 627 to Northumbria æt Bearwe Humbre c 627 to Northumbria Trent Ouestræfeld LINDESEGE c 624–33 to Northumbria TEGEINGL Gæignesburh Rhuddlan Mærse PEC- c 600 Dublin MÔN HOLY ISLAND Llanfaes Deganwy c 627 to Northumbria SÆTE to Mercia Lindcylene RHOS Saint Legaceaster Bangor Asaph Cair Segeint to Badecarnwiellon GWYNEDD WREOCAN- IRELAND Caernarvon SÆTE Bay DUNODING MIERCNA RICE Rapendun The Wash c 700 to Mercia * Usa NORTHFOLC Byrtun Elmham MEIRIONNYDD MYRCNA Northwic Cardigan Rochecestre Liccidfeld Stanford Walle TOMSÆTE MIDDIL Bay POWYS Medeshamstede Tamoworthig Ligoraceaster EAST ENGLA RICE Sæfern PENCERSÆTE WATLING STREET ENGLA * WALES MAGON- Theodford Llanbadarn Fawr GWERTH-MAELIENYDD Dommoceaster (?) RYNION RICE SÆTE Huntandun SUTHFOLC Hamtun c 656 to Mercia Beodericsworth CEREDIGION Weogornaceaster Bedanford Grantanbrycg BUELLT ELFAEL HECANAS Persore Tovecestre Headleage Rendlæsham Eofeshamm + Hereford c 600 GipeswicSutton Hoo EUIAS Wincelcumb to Mercia EAST PEBIDIOG ERGING Buccingahamm Sture mutha Saint Davids BRYCHEINIOG Gleawanceaster HWICCE Heorotford SEAXNA SAINT GEORGE’SSaint CHANNEL DYFED 577 to Wessex Ægelesburg * Brides GWENT 628 to Mercia Wæclingaceaster Hetfelle RICE Ythancæstir Llanddowror Waltham Bay Cirenceaster Dorchecestre GLYWYSING Caerwent Wealingaford WÆCLINGAS c. -

Aethelflaed: History and Legend

Quidditas Volume 34 Article 2 2013 Aethelflaed: History and Legend Kim Klimek Metropolitan State University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Renaissance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Klimek, Kim (2013) "Aethelflaed: History and Legend," Quidditas: Vol. 34 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra/vol34/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quidditas by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Quidditas 34 (2013) 11 Aethelflaed: History and Legend Kim Klimek Metropolitan State University of Denver This paper examines the place of Aethelflaed, Queen of the Mercians, in the written historical record. Looking at works like the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and the Irish Annals, we find a woman whose rule acted as both a complement to and a corruption against the consolidations of Alfred the Great and Edward’s rule in Anglo-Saxon England. The alternative histories written by the Mercians and the Celtic areas of Ireland and Wales show us an alternative view to the colonization and solidification of West-Saxon rule. Introduction Aethelflaed, Queen and Lady of the Mercians, ruled the Anglo-Sax- on kingdom of Mercia from 911–918. Despite the deaths of both her husband and father and increasing Danish invasions into Anglo- Saxon territory, Aethelflaed not only held her territory but expanded it. She was a warrior queen whose Mercian army followed her west to fight the Welsh and north to attack the Danes. -

Hijikata Tatsumi's Sabotage of Movement and the Desire to Kill The

Death and Desire in Contemporary Japan Representing, Practicing, Performing edited by Andrea De Antoni and Massimo Raveri Hijikata Tatsumi’s Sabotage of Movement and the Desire to Kill the Ideology of Death Katja Centonze (Universität Trier, Deutschland; Waseda University, Japan) Abstract Death and desire appear as essential characteristics in Hijikata Tatsumi’s butō, which brings the paradox of life and death, of stillness and movement into play. Hijikata places these con- tradictions at the roots of dance itself. This analysis points out several aspects displayed in butō’s death aesthetics and performing processes, which catch the tension between being dead and/or alive, between presence and absence. It is shown how the physical states of biological death are enacted, and demonstrated that in Hijikata’s nonhuman theatre of eroticism death stands out as an object aligned with the other objects on stage including the performer’s carnal body (nikutai). The discussion focuses on Hijikata’s radical investigation of corporeality, which puts under critique not only the nikutai, but even the corpse (shitai), revealing the cultural narratives they are subjected to. Summary 1 Deadly Erotic Labyrinth. – 2 Death Aesthetics for a Criminal and Erotic Dance. – 3 Rigor Mortis and Immobility. – 4 Shibusawa Tatsuhiko. Performance as Sacrifice and Experience. – 5 Pallor Mortis and shironuri. – 6 Shitai and suijakutai. The Dead are Dancing. – 7 The Reiteration of Death and the miira. – 8 The shitai under Critique. Death and the nikutai as Object. – 9 Against the Ideology of Death. Keywords Hijikata Tatsumi. Butō. Death. Eroticism. Corporeality. Acéphale. Anti-Dance. Body and Object. Corpse. Shibusawa Tatsuhiko. -

And Myths of Rome's Second Augusta Legion and St Augustine's 'Oak'

Trans. Bristol & Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 129 (2011), 117–137 Aust (Gloucestershire) and Myths of Rome’s Second Augusta Legion and St Augustine’s ‘Oak’ Conference By DAVID H. HIGGINS Introduction Aust in Gloucestershire has long attracted speculation over the origin of its name. The two favoured hypotheses offer an alternative: either (a) this minor ferry terminus with its settlement was named by (or after) the Second Augusta Legion of the Roman army which, stationed in full strength at Isca-Caerleon between c. 78 AD and the 3rd century, would have regularly crossed the Severn estuary from Sedbury to Aust (Augusta the claimed origin of the place-name) in order to access the main Abona (Sea Mills) to Glevum (Gloucester) artery; or (b) was named in memory of the Roman churchman St Augustine (in the later Middle Ages popularly contracted to ‘Austin’) of Canterbury who, in 603 AD (traditional date), held a conference allegedly at or hard by Aust, beneath a landmark oak tree, with leaders of the Christian Church of the autonomous British kingdom nearest to the recently converted Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Kent.1 The object of Augustine’s conference was to bring about uniformity of practice between the indigenous church of post- Roman Britain and the historic Christian church established by St Peter in the ancient capital of the Roman world. The major subjects of dispute were the British dating of Easter and the form of the baptismal rite (both, the Roman Church urged, should be Roman) and, in addition, Augustine required that the British, although understandably reluctant, should undertake the evangelisation of the pagan Anglo-Saxon invaders of their land. -

The Anglo-Saxon Origins of the West Midlands Shires

THE ANGLO-SAXON ORIGINS OF THE WEST MIDLANDS SHIRES Sheila Waddington Provincial organisation in late Anglo-Saxon England consisted of discrete territories organised to promote both defence and the maintenance of essential public works. In Mercia the territories comprised its shire structure: the regime through which defence, public works, governance, taxation, and administration of justice were undertaken. John Speed’s County Map of Staffordshire, 1611. Mary Evans Picture Library/Mapseeker Publishing Library/Mapseeker Picture 1611. Mary Evans County Map of Staffordshire, John Speed’s Shires and hundreds; Speed’s seventeenth-century map of Staffordshire reveals the units of tenth-century local government. www.historywm.com 19 ANGLO-SAXON ORIGINS OF THE SHIRES he territories which ultimately became Staffordshire, Shropshire, Warwickshire, Worcestershire, Gloucestershire, and Herefordshire have Anglo-Saxon origins. A close look at the last three shires Tsuggests the possibility of a territorial organisation dated to the British period, with bounds discernible in the Anglo-Saxon shire structure. The Shire and the Hundred The system of local government which existed over the greater part of England at the time of the Norman Conquest in 1066 had two tiers: the shire and the hundred. There is much debate about when these two structures were first in evidence in the west midlands and the more prevalent view is that they probably originated in Wessex and were later imposed early in the tenth century after the West Saxons annexed western Mercia. Both the terms ‘shire’ and ‘hundred’ are imprecise ones, and their uses, even as late as the Conquest, may be inconsistent. A ‘shire’ was the Old English word for any area of jurisdiction or control carved out of a larger one, and did not refer necessarily to a territory which later became a modern-day county.