Baseline Assessment Report -Sha Tin District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Egn201014152134.Ps, Page 29 @ Preflight ( MA-15-6363.Indd )

G.N. 2134 ELECTORAL AFFAIRS COMMISSION (ELECTORAL PROCEDURE) (LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL) REGULATION (Section 28 of the Regulation) LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL BY-ELECTION NOTICE OF DESIGNATION OF POLLING STATIONS AND COUNTING STATIONS Date of By-election: 16 May 2010 Notice is hereby given that the following places are designated to be used as polling stations and counting stations for the Legislative Council By-election to be held on 16 May 2010 for conducting a poll and counting the votes cast in respect of the geographical constituencies named below: Code and Name of Polling Station Geographical Place designated as Polling Station and Counting Station Code Constituency LC1 A0101 Joint Professional Centre Hong Kong Island Unit 1, G/F., The Center, 99 Queen's Road Central, Hong Kong A0102 Hong Kong Park Sports Centre 29 Cotton Tree Drive, Central, Hong Kong A0201 Raimondi College 2 Robinson Road, Mid Levels, Hong Kong A0301 Ying Wa Girls' School 76 Robinson Road, Mid Levels, Hong Kong A0401 St. Joseph's College 7 Kennedy Road, Central, Hong Kong A0402 German Swiss International School 11 Guildford Road, The Peak, Hong Kong A0601 HKYWCA Western District Integrated Social Service Centre Flat A, 1/F, Block 1, Centenary Mansion, 9-15 Victoria Road, Western District, Hong Kong A0701 Smithfield Sports Centre 4/F, Smithfield Municipal Services Building, 12K Smithfield, Kennedy Town, Hong Kong Code and Name of Polling Station Geographical Place designated as Polling Station and Counting Station Code Constituency A0801 Kennedy Town Community Complex (Multi-purpose -

Legislative Council Brief

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL BRIEF PUBLIC HEALTH AND MUNICIPAL SERVICES DESIGNATION OF PUBLIC LIBRARY BACKGROUND North Lamma Public Library In connection with the “Signature Project Scheme (Islands District) - Yung Shue Wan Library cum Heritage and Cultural Showroom, Lamma Island” (Project Code: 61RG), the North Lamma Public Library (NLPL) which was originally located in a one-storey building near Yung Shue Wan Ferry Pier was demolished for constructing a three-storey building to accommodate the Heritage and Cultural Showroom on the ground floor and Yung Shue Wan Public Library on the first and the second floors. Upon completion of the project, the library will adopt the previous name as “North Lamma Public Library”(南丫島北段公共圖書館) and it is planned to commence service in the second quarter of 2019. Self-service library station 2. Besides, the Leisure and Cultural Services Department (“LCSD”) has earlier launched a pilot scheme to provide three self-service library stations (“library station”), one each on Hong Kong Island, in Kowloon and in the New Territories. The library stations provide round-the-clock library services such as borrowing, return, payment and pickup of reserved library materials. 3. The locations of the three library stations are the Island East Sports Centre sitting-out area in the Eastern District, outside the Studio Theatre of the Hong Kong Cultural Centre in the Yau Tsim Mong District and an outdoor area near the Tai Wai MTR Station in the Sha Tin District respectively. The first library station in the Eastern District was opened on 5 December 2017 while the remaining two in the Yau Tsim Mong District and the Sha Tin District are tentatively planned to be opened in the fourth quarter of 2018 and the first quarter of 2019 respectively. -

HEC Minutes 2/2020 Sha Tin District Council Minutes of the 1St Special

HEC Minutes 2/2020 Sha Tin District Council Minutes of the 1st Special Meeting of the Health and Environment Committee in 2020 Date : 3 March 2020 (Tuesday) Time : 4:03 pm Venue : Sha Tin District Council Conference Room 4/F, Sha Tin Government Offices Present Title Time of joining Time of leaving the meeting the meeting Mr TING Tsz-yuen (Chairman) DC Member 4:03 pm 7:33 pm Mr CHAN Pui-ming (Vice-Chairman) ” 4:03 pm 7:33 pm Mr CHING Cheung-ying, MH DC Chairman 4:03 pm 7:33 pm Mr WONG Hok-lai, George DC Vice-Chairman 4:09 pm 7:33 pm Mr CHAN Billy Shiu-yeung DC Member 4:03 pm 7:33 pm Mr CHAN Nok-hang ” 4:03 pm 7:33 pm Mr CHAN Wan-tung ” 4:03 pm 7:33 pm Mr CHENG Chung-hang ” 4:06 pm 7:33 pm Mr CHENG Tsuk-man ” 4:03 pm 5:18 pm Mr CHEUNG Hing-wa ” 4:03 pm 7:33 pm Mr CHIU Chu-pong ” 4:03 pm 7:33 pm Mr CHOW Hiu-laam, Felix ” 4:03 pm 6:22 pm Mr CHUNG Lai-him, Johnny ” 4:03 pm 7:33 pm Mr HUI Lap-san ” 4:03 pm 7:33 pm Mr LAI Tsz-yan ” 4:09 pm 7:33 pm Dr LAM Kong-kwan ” 4:03 pm 6:38 pm Mr LI Chi-wang, Raymond ” 4:03 pm 7:33 pm Mr LI Sai-hung ” 4:03 pm 7:33 pm Mr LI Wing-shing, Wilson ” 4:09 pm 7:19 pm Mr LIAO Pak-hong, Ricardo ” 4:03 pm 4:37 pm Mr LO Tak-ming ” 4:03 pm 7:33 pm Mr LUI Kai-wing ” 4:03 pm 7:10 pm Ms LUK Tsz-tung ” 4:07 pm 6:15 pm Mr MAK Tsz-kin ” 4:03 pm 6:13 pm Mr MAK Yun-pui, Chris ” 4:06 pm 7:33 pm Mr MOK Kam-kwai, BBS ” 4:03 pm 5:33 pm Mr NG Kam-hung ” 4:03 pm 7:33 pm Ms NG Ting-lam ” 4:03 pm 6:22 pm Mr SHAM Tsz-kit, Jimmy ” 4:03 pm 7:33 pm Mr SHEK William ” 4:09 pm 7:33 pm Mr SIN Cheuk-nam ” 4:03 pm 5:18 pm Mr TSANG Kit ” 4:03 -

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Thursday, 12 July

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 12 July 2007 10569 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Thursday, 12 July 2007 The Council continued to meet at Nine o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE MRS RITA FAN HSU LAI-TAI, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TIEN PEI-CHUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LUI MING-WAH, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE MRS SELINA CHOW LIANG SHUK-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN YUEN-HAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE BERNARD CHAN, G.B.S., J.P. 10570 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 12 July 2007 THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE SIN CHUNG-KAI, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE HOWARD YOUNG, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE YEUNG SUM, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU CHIN-SHEK, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. -

List of Recognized Villages Under the New Territories Small House Policy

LIST OF RECOGNIZED VILLAGES UNDER THE NEW TERRITORIES SMALL HOUSE POLICY Islands North Sai Kung Sha Tin Tuen Mun Tai Po Tsuen Wan Kwai Tsing Yuen Long Village Improvement Section Lands Department September 2009 Edition 1 RECOGNIZED VILLAGES IN ISLANDS DISTRICT Village Name District 1 KO LONG LAMMA NORTH 2 LO TIK WAN LAMMA NORTH 3 PAK KOK KAU TSUEN LAMMA NORTH 4 PAK KOK SAN TSUEN LAMMA NORTH 5 SHA PO LAMMA NORTH 6 TAI PENG LAMMA NORTH 7 TAI WAN KAU TSUEN LAMMA NORTH 8 TAI WAN SAN TSUEN LAMMA NORTH 9 TAI YUEN LAMMA NORTH 10 WANG LONG LAMMA NORTH 11 YUNG SHUE LONG LAMMA NORTH 12 YUNG SHUE WAN LAMMA NORTH 13 LO SO SHING LAMMA SOUTH 14 LUK CHAU LAMMA SOUTH 15 MO TAT LAMMA SOUTH 16 MO TAT WAN LAMMA SOUTH 17 PO TOI LAMMA SOUTH 18 SOK KWU WAN LAMMA SOUTH 19 TUNG O LAMMA SOUTH 20 YUNG SHUE HA LAMMA SOUTH 21 CHUNG HAU MUI WO 2 22 LUK TEI TONG MUI WO 23 MAN KOK TSUI MUI WO 24 MANG TONG MUI WO 25 MUI WO KAU TSUEN MUI WO 26 NGAU KWU LONG MUI WO 27 PAK MONG MUI WO 28 PAK NGAN HEUNG MUI WO 29 TAI HO MUI WO 30 TAI TEI TONG MUI WO 31 TUNG WAN TAU MUI WO 32 WONG FUNG TIN MUI WO 33 CHEUNG SHA LOWER VILLAGE SOUTH LANTAU 34 CHEUNG SHA UPPER VILLAGE SOUTH LANTAU 35 HAM TIN SOUTH LANTAU 36 LO UK SOUTH LANTAU 37 MONG TUNG WAN SOUTH LANTAU 38 PUI O KAU TSUEN (LO WAI) SOUTH LANTAU 39 PUI O SAN TSUEN (SAN WAI) SOUTH LANTAU 40 SHAN SHEK WAN SOUTH LANTAU 41 SHAP LONG SOUTH LANTAU 42 SHUI HAU SOUTH LANTAU 43 SIU A CHAU SOUTH LANTAU 44 TAI A CHAU SOUTH LANTAU 3 45 TAI LONG SOUTH LANTAU 46 TONG FUK SOUTH LANTAU 47 FAN LAU TAI O 48 KEUNG SHAN, LOWER TAI O 49 KEUNG SHAN, -

Electoral Affairs Commission Report

i ABBREVIATIONS Amendment Regulation to Electoral Affairs Commission (Electoral Procedure) Cap 541F (District Councils) (Amendment) Regulation 2007 Amendment Regulation to Particulars Relating to Candidates on Ballot Papers Cap 541M (Legislative Council) (Amendment) Regulation 2007 Amendment Regulation to Electoral Affairs Commission (Financial Assistance for Cap 541N Legislative Council Elections) (Application and Payment Procedure) (Amendment) Regulation 2007 APIs announcements in public interest APRO, APROs Assistant Presiding Officer, Assistant Presiding Officers ARO, AROs Assistant Returning Officer, Assistant Returning Officers Cap, Caps Chapter of the Laws of Hong Kong, Chapters of the Laws of Hong Kong CAS Civil Aid Service CC Complaints Centre CCC Central Command Centre CCm Complaints Committee CE Chief Executive CEO Chief Electoral Officer CMAB Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Bureau (the former Constitutional and Affairs Bureau) D of J Department of Justice DC, DCs District Council, District Councils DCCA, DCCAs DC constituency area, DC constituency areas DCO District Councils Ordinance (Cap 547) ii DO, DOs District Officer, District Officers DPRO, DPROs Deputy Presiding Officer, Deputy Presiding Officers EAC or the Commission Electoral Affairs Commission EAC (EP) (DC) Reg Electoral Affairs Commission (Electoral Procedure) (District Councils) Regulation (Cap 541F) EAC (FA) (APP) Reg Electoral Affairs Commission (Financial Assistance for Legislative Council Elections and District Council Elections) (Application and Payment -

New Territories

New Territories Opening Hour Opening Hour District Code Locker Full Address (Sun and Public (Mon to Sat) Holidays) Locker No.2, Shop 16A, 17, G/F, Holford Garden, Tai Wai, Sha Tin District, New Territories, Hong Tai Wai H852FG97P 24Hours 24Hours Kong(SF Locker) Shop 7, G/F, Chuen Fai Centre, 9-11 Kong Pui Street, Sha Tin, Sha Tin District, New Territories, Hong H852FE43P 24Hours 24Hours Kong(SF Locker) Unit A9F, G/F, Koon Wah Building, 2 Yuen Shun Circuit, Sha Tin, Sha Tin District, New Territories, Hong H852FB25P 24Hours 24Hours Kong(SF Locker) Sha Tin H852FB90P Shop 238-239, 2/F, King Wing Plaza 2, Sha Tin, Sha Tin District, New Territories, Hong Kong(SF Locker)+ 09:00-23:30 09:00-23:30 Locker No.2, Shop 238-239, 2/F, King Wing Plaza 2, Sha Tin, Sha Tin District, New Territories, Hong H852FB91P 09:00-23:30 09:00-23:30 Kong(SF Locker)+ Locker No.3, Shop 238-239, 2/F, King Wing Plaza 2, Sha Tin, Sha Tin District, New Territories, Hong H852FB92P 09:00-23:30 09:00-23:30 Kong(SF Locker)+ H852FE80P Locker No.1, Shop No. 9, G/F, We Go Mall, 16 Po Tai Street, Ma On Shan, New Territories (SF Locker) 24Hours 24Hours Ma On Shan H852FE81P Locker No.2, Shop No. 9, G/F, We Go Mall, 16 Po Tai Street, Ma On Shan, New Territories (SF Locker) 24Hours 24Hours Shop F20 ,1/F, Commercial Centre Saddle Ridge Garden ,6 Kam Ying Road, Sha Tin, Sha Tin District, New H852FE02P 04:00-02:00 04:00-02:00 Territories, Hong Kong(SF Locker) Locker No.1,SF Store,G/F,Tai Wo Centre, 15 Tai Po Tai Wo Road, Tai Po, Tai Po District, New Territories, H852AA83P 24Hours 24Hours Hong Kong(SF Locker) Locker No.2, SF Store,G/F, Tai Wo Centre, 15 Tai Po Tai Wo Road, Tai Po, Tai Po District, New Territories, H852AA84P 24Hours 24Hours Tai Po Hong Kong(SF Locker) Shop B, G/F, Hei Tai Building, 19 Pak Shing Street, Tai Po, Tai Po District, New Territories, Hong Kong(SF H852AA10P 24Hours 24Hours Locker) H852AA82P Shop C, G/F, 3 Kwong Fuk Road, Tai Po, Tai Po District, New Territories, Hong Kong(SF Locker) 24Hours 24Hours Shop 124, Flora Plaza, no. -

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 11

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 11 February 2015 6007 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 11 February 2015 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE VINCENT FANG KANG, S.B.S., J.P. 6008 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 11 February 2015 THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-HING, B.B.S., M.H. PROF THE HONOURABLE JOSEPH LEE KOK-LONG, S.B.S., J.P., Ph.D., R.N. THE HONOURABLE JEFFREY LAM KIN-FUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW LEUNG KWAN-YUEN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG TING-KWONG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE RONNY TONG KA-WAH, S.C. THE HONOURABLE CYD HO SAU-LAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE STARRY LEE WAI-KING, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LAM TAI-FAI, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAK-KAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KIN-POR, B.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PRISCILLA LEUNG MEI-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. -

List of Abbreviations

MJ T`Wbb_b] M^c_Y[f 0;BC ?: +66A9E;5C;?> Q_fg c\ KXXe[i_Wg_cb List of Abbreviation Name/Organization Abbreviation Paragraph Index Advisory Council on the Environment ACE A3-1, A4-21, B1-24, C1-54, C4-13, C7-3, C7-18, C9-8, D4-1, D5-3 Advisory Council on the Environment – ACE-EIA Subcom B1-1, B2-5, C4-50, C7-6, C7-9, Environmental Impact Assessment C7-16, D3-2, D6-32, D9-9 Subcommittee Antiquities Advisory Board AAB A4-22, A4-33, B1-1, D5-13, D5-18, D5-33 Apple Daily Apple C4-30, D2-1, D3-1, D3-10, D10-32 Au, Joanlin Chung Leung J. Au B2-19, D10-10 Best Galaxy Ltd. BG Ltd. C4-19, C4-27, C4-49 Charter Rank Ltd. CR Ltd. Brown, Stephen S. Brown B1-1, B1-2, B1-16, B1-17, B1-23, D2-1, D2-9, D2-14, D5-15, D5-20, D8-1 Central & Western District Council C&W DC A2-12, B1-1, C3-3, C3-17, C3-20, C4-65, D2-1, D2-3, D2-4, D2-16, D3-14, D5-19, D5-29, D5-31, D9-1, D9-8, D10-21 Chan, Albert W.Y. A. Chan D2-14 Chan, Ho Kai* H.K. Chan C3-13, C4-1, D5-37, D5-39 Chan, Ling* L. Chan A4-25, D10-4 Chan, Raymond R. Chan A4-9, B1-7, C2-15, C2-19, C2-50, Cheng, Samuel S. Cheng C3-10, D6-4, D6-7, D6-19, D6-29, Kwok, Sam S. -

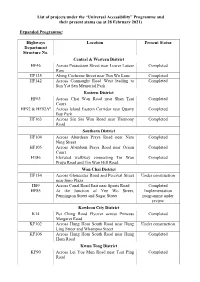

List of Projects Under the “Universal Accessibility” Programme and Their Present Status (As at 28 February 2021)

List of projects under the “Universal Accessibility” Programme and their present status (as at 28 February 2021) Expanded Programme: Highways Location Present Status Department Structure No. Central & Western District HF46 Across Possession Street near Lower Lascar Completed Row HF135 Along Cochrane Street near Tun Wo Lane Completed HF142 Across Connaught Road West leading to Completed Sun Yat Sen Memorial Park Eastern District HF63 Across Chai Wan Road near Shan Tsui Completed Court HF92 & HF92A# Across Island Eastern Corridor near Quarry Completed Bay Park HF163 Across Siu Sai Wan Road near Harmony Completed Road Southern District HF104 Across Aberdeen Praya Road near Nam Completed Ning Street HF105 Across Aberdeen Praya Road near Ocean Completed Court H186 Elevated walkway connecting Tin Wan Completed Praya Road and Tin Wan Hill Road Wan Chai District HF154 Across Gloucester Road and Percival Street Under construction near Sino Plaza HS9 Across Canal Road East near Sports Road Completed HF85 At the Junction of Yee Wo Street, Implementation Pennington Street and Sugar Street programme under review Kowloon City District K14 Pui Ching Road Flyover across Princess Completed Margaret Road KF102 Across Hung Hom South Road near Hung Under construction Ling Street and Whampoa Street KF106 Across Hung Hom South Road near Hung Completed Hom Road Kwun Tong District KF90 Across Lei Yue Mun Road near Tsui Ping Completed Road Highways Location Present Status Department Structure No. KF109 Across Shun Lee Tsuen Road near Shun Completed Lee Estate -

Barrier-Free Banking Services

Measures to improve branch services to customers with disabilities Wheelchair Provision of a Provision of a Portable Tac tile at Guide dogs District Branch Name Branch Address Branch Tel. access to branch permanent temporary Call Button Induction staircase are welcomed area available ramp ramp Loop Kit Central and Western Head Office Branch G/F, The Center, 99 Queen's Road Central, H.K. (852) 3668 2000 P P P P District Shop A&B, G/F and Unit A&B, 1/F., On Tai Building, 1-3 Wu Nam Street, Southern District Aberdeen Branch (852) 3668 2360 P P P P P P Aberdeen, Hong Kong Kwun Tong District Amoy Plaza Branch Shops G193-195, Amoy Plaza, 77 Ngau Tau Kok Road, Ngau Tau Kok, Kowloon (852) 3668 2720 P P P P P DBS Treasures at Causeway Wan Chai District G/F., 12-14 Yee Wo Street, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong (852) 3668 2200 P P P P P P Bay Central and Western Des Voeux Road Central Basement, G/F, 1/F and 7/F., 39-41 Des Voeux Road Central, Central, Hong (852) 3668 2080 P P P P P P District Branch Kong Wan Chai District Hennessy Road Branch 427-429 Hennessy Road, Causeway Bay, H.K. (852) 3668 2160 P P P P P P Kwun Tong District Hoi Yuen Road Branch Unit 2, G/F., Hewlett Centre, 54 Hoi Yuen Road, Kwun Tong, Kowloon (852) 3668 2690 P P P P P Kwai Tsing District Kwai Chung Branch G/F., 1001 Kwai Chung Road, Kwai Chung, New Territories (852) 3668 2780 P P P P P P Sha Tin District Ma On Shan Branch Shop 205-206, Level 2, Ma On Shan Plaza, Ma On Shan, New Territories (852) 3668 2870 P P P P Shops N26A - N26B, Stage V, Mei Foo Sun Chuen, 10 & 12 Nassau Street, Sham Shui Po District Mei Foo Branch (852) 3668 2600 P P P P P Kowloon Yau Tsim Mong DBS Treasures at Kowloon G/F., 728-730 Nathan Road, Mong Kok, Kowloon (852) 3668 6970 P P P P P P District Eastern District North Point Branch G/F., 391 King's Road, North Point, Hong Kong (852) 3668 2250 P P P P P P Eastern District Quarry Bay Branch Shop A, G/F., 1063 King's Road, Quarry Bay, Hong Kong (852) 3668 2280 P P P P P DBS Treasures at Queen's Shop A, G/F. -

Hansard (English)

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 26 January 2011 5291 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 26 January 2011 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. 5292 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 26 January 2011 THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW CHENG KAR-FOO THE HONOURABLE TIMOTHY FOK TSUN-TING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LI FUNG-YING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P.